![]()

Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888

| Artist | Claude Monet, French, 1840–1926 |

| Title | Mill at Limetz |

| Object Date | 1888 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Moulin de Limetz; Moulin de Limetz sur l’Epte; le vieux moulin |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 36 3/4 x 29 in. (93.4 x 73.7 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower right: Claude Monet 88 |

| Credit Line | Former collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, D38-1986. At the time of publication, this painting was a partial bequest from Ethel B. Atha to the museum, where it was intermittently exhibited from 1986 to 2024. |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.630.5407.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.630.5407.

My dear mother, I have unconsciously let the time slip by without giving you a word of the new settlement which we have formed here in this most beautiful part of France, the river Seine running by almost at our door. The village is far, far ahead of Barbizon in every respect.6Joan Murray, ed., Letters Home: 1859–1906; The Letters of William Blair Bruce (Moonbeam, ON: Penumbra, 1982), 123.

Over the course of the next few months, Bruce completed The Bridge at Limetz, which is a combination of landscape and genre scene. He wrote to his future wife, Swedish sculptor Carolina Benedicks (1856–1935), that he was “afraid of mechanically finishing a thing that I would prefer to leave in parts quite ‘ébauché.’”7William Blair Bruce to Caroline Benedicks, August 10, 1887. Cited in Gerdts, “‘The most beautiful country that I have ever visited’,” in Bruce, ed., Into the Light, 117. Bruce had studied at Paris’s Académie Julian under William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905) and Tony Robert-Fleury (1837–1911) and had enjoyed some success at the Salon with his genre scenes.8See, for example, Temps passé of 1884 (Owens Art Gallery, Mount Allison University, Sackville, NB). Upon arriving in Giverny, Bruce took the suggestion of his friend Robinson and lightened up his palette.

In The Bridge at Limetz, the mill is blanched in the strong summer sunshine. It appears whitewashed in more ways than one; not only does the light bleach out cracks and dirt in the building’s surface, but the men laboring to lift grain into the mill appear to do so without difficulty. In the middle ground, a man on the bridge stops to speak with a washerwoman sitting on the banks of the Epte. The result is an image of rustic harmony and simplicity rendered in bright whites, blues, and greens. As Bruce scholar Joan Murray notes,

Bruce’s aims seem similar to those of the Impressionists: to represent the appearance of the world out of doors as it is affected by light, reflection, and atmosphere, and to convey the sharpness and freshness of the initial sensation. However, his academic training was always apparent in his thought and subject matter. He always analyzed what rather than how he saw.9Murray, Letters Home, 15. Emphasis original.

Bruce’s letters also display his interest in the “what”; when discussing the picture with his loved ones, he notes trudging a mile a day from Giverny to Limetz-Villez and leaving his canvas with the mill owner at the close of each painting session.10Gerdts, “‘The most beautiful country that I have ever visited’,” in Bruce, ed., Into the Light, 119. While Bruce certainly had aesthetic interests, as evidenced by his major tonal shift after his arrival in Giverny, the topography and anecdotal details of life in rural France take the lead in his canvases.

A year later, Monet emphasized the “how” over the “what” in his two Mill at Limetz canvases. Both pictures relegate the mill to a supporting role; it is only nominally the subject of the paintings. The setting provided the artist with an idyllic backdrop for his primary interests in light, color, and reflection. Bruce’s picture hints at nature, but the river flowing under the bridge and the trees are framing elements for human activity. He drew heavily upon photographic precedents, and his composition strongly resembles that seen in postcards. Monet, in contrast, wandered farther down the Epte from Bruce’s position at one end of the bridge, positioning himself on the riverbank itself, with a willow tree partially obstructing his view of the mill. In both Monet paintings, the willow tree dominates our view. The mill and bridge of the Nelson-Atkins picture are a sparkling blend of yellow, violet-blue, and pink pigments, while the mill in the Potsdam version is even less modeled and dissolves into a yellow-green blur. Gone are the village inhabitants hard at work and the backdrop of farm fields in favor of two color studies concerned more with atmospheric effects than anecdotes. Monet chose not to alter his composition between the two versions, nor did he alter their size. The paintings thus welcome contemplation as a pair, despite not having shared wall space since the 1889 exhibition of works by Monet and the sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) at Galerie Georges Petit, Paris.11The two mill paintings had numbers 119 and 122 in the exhibition. Claude Monet; A. Rodin, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit,1889), 41, reprinted in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris:Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 34, Miscellaneous Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981). It is unclear which version Monet painted first, but we can imagine him working on these canvases at the same time and puzzling out how to render the wall of foliage in both pictures. Monet’s approaches to the willow tree are early manifestations of his passion for seriality, more fully expressed in his Haystack (1890–91), Poplars on the Epte (1891), and Rouen Cathedral (1892–94) paintings. Without changing his position, Monet gives the viewer two drastically different atmospheres by capturing the light effects as they fall on the scene. This is most apparent in the treatment of foliage, which appears as a dark, solid wall of mossy green leaves in the Potsdam version and is transformed by highlights in the Nelson-Atkins picture into a much lighter bower. The contrast between pink mill and green willow is much clearer in the Nelson-Atkins painting, which also gives the viewer more of a sense of depth.

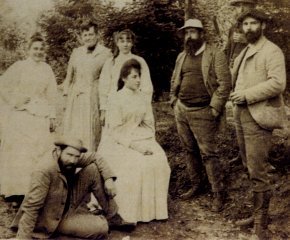

Fig. 5. John Leslie Breck (seated bottom left), Claude Monet (second from right, standing), and the Monet-Hoschedé family, ca. 1887–90, photograph, courtesy of Brown Corbin Fine Art, Milton, MA

Fig. 5. John Leslie Breck (seated bottom left), Claude Monet (second from right, standing), and the Monet-Hoschedé family, ca. 1887–90, photograph, courtesy of Brown Corbin Fine Art, Milton, MA

Fig. 6. Theodore Robinson (American, 1852–96), Road by the Mill, 1892, oil on canvas, 20 x 25 in. (50.8 x 63.5 cm), Cincinnati Art Museum; Gift of Alfred T. and Eugenia I. Goshorn

Fig. 6. Theodore Robinson (American, 1852–96), Road by the Mill, 1892, oil on canvas, 20 x 25 in. (50.8 x 63.5 cm), Cincinnati Art Museum; Gift of Alfred T. and Eugenia I. Goshorn

The mills in and around Giverny and Limetz-Villez guaranteed that artists in the region were never lacking for subject matter. The number of takes on this motif speaks to the centrality of the mills to life in the area. North American artists were enthralled by the opportunity to capture the topography of this region that was so new to them. While they did not abandon their academic adherence to composition and narrative, Bruce, Breck, Robinson, and their peers did adopt the high-keyed tones and more gestural brushwork generally associated with Impressionism. Monet had lived in Giverny since 1883, and so his two mill paintings approach the subject matter in a less touristic fashion. In his canvases, the natural beauty of Limetz-Villez predominates over the structure of its landmarks. All four depictions of the Limetz-Villez mill, and Robinson’s works featuring the mills of Giverny, are evidence of a friendly competition of ideas and approaches to painting. Monet was intimately aware of the motifs popular among the younger generation, especially by 1888, when he struck up a friendship with Robinson. The artists’ colony at Giverny should, therefore, be understood less as a hub-and-spoke entity, with a master at the center, than as a constellation of creatives of varying levels of skill who reveled in the opportunity to render familiar scenes in their own style.

Notes

-

The River Epte is a tributary of the River Seine, flowing through both Giverny and Limetz-Villez.

-

An 1836 steamboat tour guidebook highlighted both Giverny and Limetz-Villez for their small populations (396 and 864, respectively) and dependence on agriculture. Most importantly, the guidebook notes that “the River Epte turns two mills” in the area. The inclusion of the local mills in the short descriptions in a tourist guidebook speaks to their dominance of the landscape. Saint-Edme, Itinéraire des bateaux à vapeur de Paris à Rouen: avec une description statistique, historique et anecdotique des bords de la Seine; suivi d’un Guide du voyageur (Paris: E. Bourdin, 1836), 84.

-

The artist’s colony at Giverny is well researched and documented. John Leslie Breck, William Blair Bruce, Theodore Robinson, Willard Metcalf, Louis Ritter, Theodore Wendel, and Theodore Earl Butler initially lived together in Giverny. For a fuller account, see William H. Gerdts, Monet’s Giverny: An Impressionist Colony (New York: Abbeville, 1993); Susan Behrends Frank, American Impressionists: Painters of Light and the Modern Landscape, exh. cat. (New York: Rizzoli, 2007); and Sona Johnston, In Monet’s Light: Theodore Robinson at Giverny, exh. cat. (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 2004).

-

From Bruce’s extensive correspondence with the Swedish sculptor Caroline Benedicks, whom he would later marry, we know that the painter began The Bridge at Limetz around July 17, 1887. Cited in William H. Gerdts, “‘The most beautiful country that I have ever visited’: William Blair Bruce in Giverny,” in Tobi Bruce, ed., Into the Light: The Paintings of William Blair Bruce (1859–1906), exh. cat. (Hamilton, ON: Art Gallery of Hamilton, 2014), 119.

-

Gerdts, “‘The most beautiful country that I have ever visited’,” in Bruce, ed., Into the Light, 119.

-

Joan Murray, ed., Letters Home: 1859–1906; The Letters of William Blair Bruce (Moonbeam, ON: Penumbra, 1982), 123.

-

William Blair Bruce to Caroline Benedicks, August 10, 1887. Cited in Gerdts, “‘The most beautiful country that I have ever visited’,” Bruce, ed., Into the Light, 117.

-

See, for example, Temps passé of 1884 (Owens Art Gallery, Mount Allison University, Sackville, NB).

-

Murray, Letters Home, 15. Emphasis original.

-

Gerdts, “‘The most beautiful country that I have ever visited’,” in Bruce, ed., Into the Light, 119.

-

The two mill paintings had numbers 119 and 122 in the exhibition. Claude Monet; A. Rodin, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1889), 41, reprinted in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 34, Miscellaneous Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981).

-

This series has been explored in depth for its relationship to Monet’s series in Rolf H. Krauss, “Claude Monet, John Leslie Breck und die Getreideschober, oder das Prinzip Serie und die Photographie,” Kritische Berichte 33 (2005): 77–91.

-

Monet commented on Robinson’s painting around September 15, 1892. Robinson worked on smaller mill canvases into November and used photographs of the mill to further his project back home in New York. Monet criticism cited in Gerdts, Monet’s Giverny, 93–94.

-

Theodore Robinson, “Claude Monet,” The Century 44 (September 1892): 701.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, stock no. 1073, as Moulin de Limetz sur l’Epte, July 20, 1891–June 9, 1902 [1];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, by Lucien Sauphar (1856–1935), Paris, 1902–August 23, 1935;

Purchased from his posthumous sale, Succession de Mr Lucien Sauphar: Tableaux modernes par Boudin, Guillaumin, Jongkind, Laprade, Lebourg, Lépine, Marquet, Odilon Redon, Dunoyer de Segonzac; Œuvres importantes de Claude Monet et de Sisley; Objets de Vitrine, Sculptures, Pendules, Bronzes, Sièges et Meubles du XVIIIe Siècle, estampilliés de Nogaret, H. Jacob, Brizard, Hansen, Héricourt, etc.; Collection de Verrerie Ancienne art Arabe, Venise, Allemagne, etc., Paravents en Laque de Coromandel; Importants Bijoux Collier, Bagues, Broche, Bracelets, Sautoirs, Galerie Jean Charpentier, Paris, March 17, 1936, no. 26, as Le vieux moulin, by Durand-Ruel, Paris, for Durand-Ruel, New York, stock no. 5305, in half-share with Knoedler and Co., New York, stock no. A1658, as Le vieux moulin, 1936–October 25, 1941 [2];

Purchased from Knoedler and Company, New York, by Joseph Samuel (1898–1970) and Ethel Bonita (née Shufflebotham, 1899–1986) Atha, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1941–July 6, 1986 [3];

Partial bequest of Ethel B. Atha to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1986.

Notes

[1] See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file.

[2] The painting was registered in Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock book as Deposit 15840 from Durand-Ruel, New York. It was transferred from Durand-Ruel, Paris, to Durand-Ruel, New York, in May 1936. Durand-Ruel sold their half-share to Knoedler on November 19, 1941. See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. Knoedler purchased a half-share of the painting, on April 13, 1936, no. A1658, as Le vieux moulin. See “Knoedler Book 8, April 13, 1936–October 25, 1941, Page 154, Row 3, Stock No. A1658,” The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Dealer Stock Books, as Le vieux moulin.

[3] Durand-Ruel sold their half-share to Knoedler on November 19, 1941. See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file. See “Knoedler Book 8, April 13, 1936–October 25, 1941, Page 154, Row 3, Stock No. A1658,” The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Dealer Stock Books, as Le vieux moulin.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

Claude Monet, Moulin sur l’Epte (Mill on the Epte), 1888, oil on canvas, 35.4 x 28.3 in (90 x 72 cm), Museum Barberini, Potsdam, inv. MB-Mon-39.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

Claude Monet; A. Rodin, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, opened June 21, 1889, no. 122, as Moulin de Limetz.

Tableaux de Monet, Pissarro, Renoir et Sisley, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, April 1899, no. 29, as Moulin sur l’Epte.

Exposition Claude Monet: organisée au bénéfice des Victimes de la Catastrophe du Japon, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, January 4–18, 1924, no. 5, as Le Moulin d’Epte.

Impressionism: Selections From Five American Museums, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, November 4–December 31, 1989; Minneapolis Institute of Arts, January 27–March 25, 1990; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 21–June 17, 1990; Saint Louis Art Museum, July 14–September 9, 1990; Toledo Museum of Art, September 30–November 25, 1990, hors cat., as Mill at Limetz (NAMA only).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier “Claude Monet, Mill at Limetz, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.630.4033.

Claude Monet; A. Rodin, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Georges Petit, 1889), 41 [repr., in Theodore Reff, ed., Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 34, Miscellaneous Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Moulin de Limetz.

Gustave Geffroy, La vie artistique, Troisième série: Histoire de l’impressionnisme (Paris: E. Dentu, 1894), 85–86.

Exposition de tableaux de Monet, Pissarro, Renoir et Sisley, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1899), 6 [repr., in Theodore Reff, Modern Art in Paris: Two-Hundred Catalogues of the Major Exhibitions Reproduced in Facsimile in Forty-Seven Volumes, vol. 23, Impressionist Group Exhibitions (New York: Garland, 1981), unpaginated], as Moulin sur l’Epte.

Gustave Geffroy, Claude Monet, sa vie, son temps, son œuvre (Paris: Les Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1922), 118, as Moulin sur l’Epte.

Gustave Geffroy, Claude Monet, sa vie, son œuvre (Paris: Les Éditions G. Crès et Cie, 1924), 1:197, 214, as Moulin sur l’Epte.

Gustave Geffroy and Léonce Bénédite, Exposition Claude Monet: organisée au bénéfice des Victimes de la Catastrophe du Japon, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Georges Petit, 1924), 11, as Le Moulin d’Epte.

Succession de Mr Lucien Sauphar: Tableaux modernes par Boudin, Guillaumin, Jongkind, Laprade, Lebourg, Lépine, Marquet, Odilon Redon, Dunoyer de Segonzac; Œuvres importantes de Claude Monet et de Sisley; Objets de Vitrine, Sculptures, Pendules, Bronzes, Sièges et Meubles du XVIIIe Siècle; estampillés de Nogaret, H. Jacob, Brizard, Hansen, Héricourt, etc.; Collection de Verrerie Ancienne art Arabe, Venise, Allemagne, etc., Paravents en Laque de Coromandel; Importants Bijoux Collier, Bagues, Broche, Bracelets, Sautoirs (Paris: Galerie Jean Charpentier, March 17, 1936), unpaginated, (repro.), as Le vieux moulin.

G.-S. Mercier, “Mouvement Artistique: A [sic] l’exposition de la ‘cité moderne’, Question de prix,” L’Écho d’Alger, no. 9382 (April 12, 1936): 8.

D. de Charnage, “Chronique artistique: Les grandes ventes,” La Croix, no. 16,412 (August 18, 1936): unpaginated, as le Vieux Moulin.

Oscar Reuterswärd, Monet: En konstnärshistorik (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers Förlag, 1948), 183, (repro.), as Vattenkvarnen vid Limetz.

Denis Rouart and Jean-Dominique Rey, Monet: Nymphéas ou les miroirs du temps (Paris: Fernand Hazan, 1972), 72–73, (repro.), as Moulin de Limetz sur les bords de l’Epte.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Biographie et catalogue raisonné, vol. 3, 1887–1898: Peintures (Lausanne, Switzerland: La Bibliothèque des Arts, 1974), no. 1210, pp. 116–17, 306–07, 312, (repro.) as Moulin de Limetz.

David Lewis, “Museum Impressions,” Carnegie Magazine 59, no. 12 (November–December 1989): 46.

Roger Ward, “Selected Acquisitions of European and American Paintings at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, 1986–1990: Supplement,” Burlington Magazine 133, no. 1055 (February 1991): 155–56, (repro.), as Moulin de Limetz.

Daniel Wildenstein, Claude Monet: Catalogue raisonné, vol. 5, Supplément aux peintures, Dessins, Pastels, Index (Lausanne, Switzerland: Wildenstein Institute, 1991), no. 1210, pp. 292, 330, 337.

William H. Gerdts, Monet’s Giverny: An Impressionist Colony (New York: Abbeville, 1992), 17, 96, as Limetz Mill.

Bernard Denvir, The Chronicle of Impressionism: An Intimate Diary of the Lives and World of the Great Artists (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 279.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills, 1993), 211, (repro.), as Mill at Limetz.

“Music Teachers National Association National Convention, March 23–27, 1996, Kansas City, Missouri,” American Music Teacher 45, no. 4 (February–March 1996): 23.

Daniel Wildenstein, Monet: Catalogue Raisonné; Werkverzeichnis, vol. 3, Nos. 969–1595 (Cologne: Benedikt Taschen Verlag GmbH, 1996), no. 1210, p. 460, (repro.), as Moulin de Limetz, The Mill at Limetz, and Mühle von Limetz.

Joseph Baillio, Claude Monet (1840–1926): A Tribute to Daniel Wildenstein and Katia Granoff, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 2007), 140, as Moulin de Limetz.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 124, (repro.), as Mill at Limetz.

Alice Thorson, “Three Times the Wonder: Claude Monet’s later work reflects his obsession with the color and reflections in his water garden,” Kansas City Star Magazine, supplement, Kansas City Star 131, no. 198 (April 3, 2011): S9, as The Mill at Limetz.

Nina Siegal, “Upon Closer Review, Credit Goes to Bosch,” New York Times 165, no. 57130 (February 2, 2016): C5.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.W-NK75NKhaQs

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 94, (repro.), as Mill at Limetz.