![]()

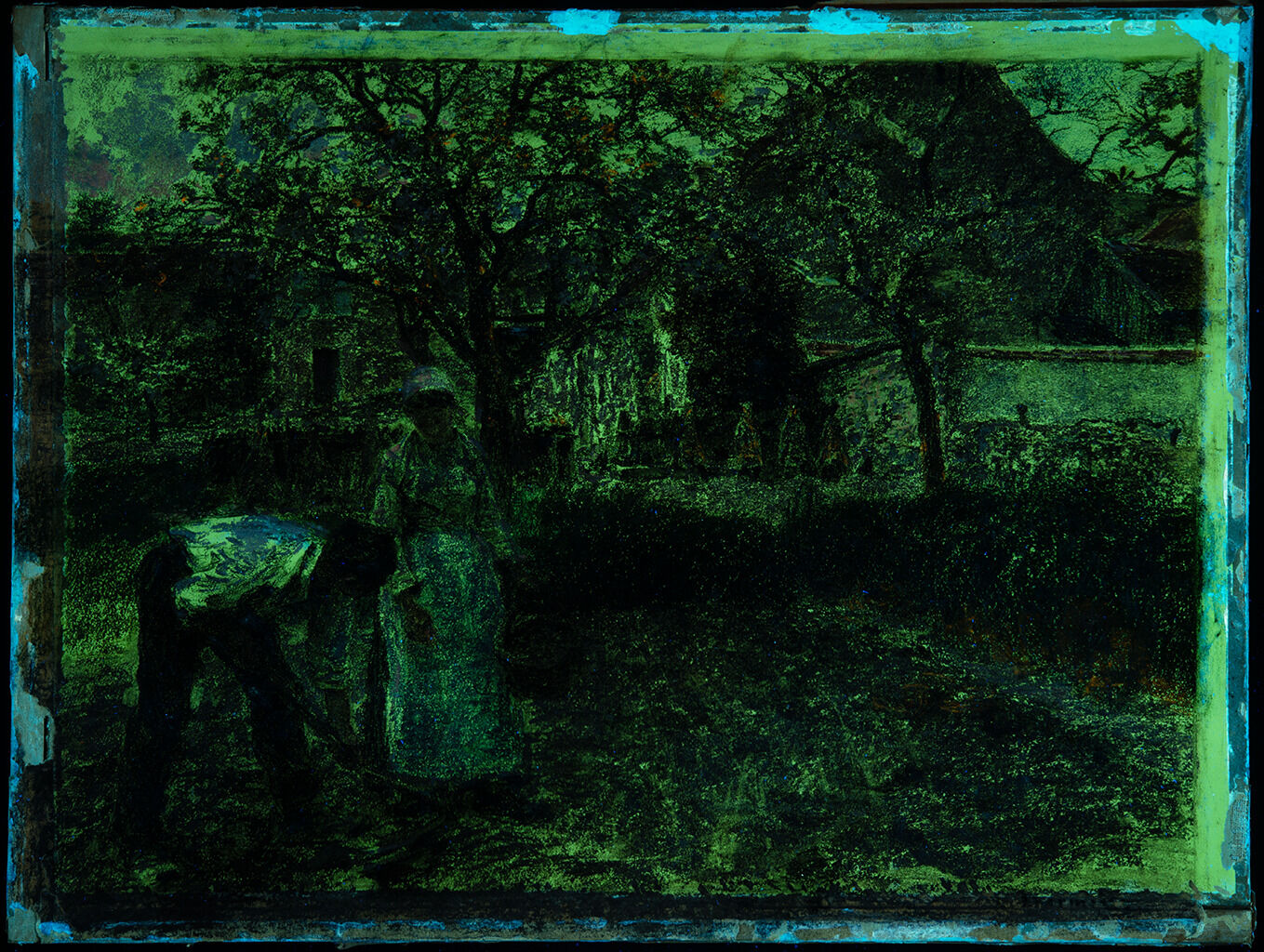

Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888

| Artist | Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, French, 1844–1925 |

| Title | Potato Planting in Spring |

| Object Date | 1888 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | La plantation des pommes de terre au printemps; La plantation des pommes de terre |

| Medium | Pastel and charcoal on paper, mounted on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 16 7/8 × 22 3/8 in. (42.9 × 56.8 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower right: L. L hermitte |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of James W. Sight and Dr. Heidi Harman in honor of the 75th anniversary of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2014.21 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.624.5407.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.624.5407.

In 1888, the same year Léon-Augustin Lhermitte completed the Nelson-Atkins pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss. Potato Planting in Spring, he illustrated a book entitled La Vie Rustique by his friend André Theuriet, a poet, novelist, and playwright. Theuriet described their approach to the subject of rustic life in the introduction:

We have tried to piously collect here the relics of these customs, these faces and these landscapes which are about to disappear—and we will be amply rewarded for our efforts, if we have thus been able to preserve for our great-nephews the picture of a world and a nature they may no longer know.1Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author’s. “Nous avons essayé d’y recueillir pieusement les reliques de ces mœurs, de ces physionomies et de ces paysages qui vont disparaître,—et nous serons largement récompensés de nos eftorts, si nous avons pu ainsi conserver à nos arrière-neveux le tableau d’un monde et d’une nature qu’ils ne connaîtront peut-être plus.” See André Theuriet and Léon Augustin Lhermitte, La vie rustique (Paris: Launette, 1888), viii.

Indeed, farming and rustic life were at a moment of great transition in the mid- to late nineteenth century, set against the backdrop of the industrial revolution.2An important earlier publication on this subject is Eugene Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: Modernization of Rural France, 1870–1914 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1979). And yet, no evidence of that shift is present in the Nelson-Atkins composition, in which Lhermitte depicts a rural worker who digs a trench by hand in a small garden, preparing the soil for his female counterpart to place a potato tuber. Setting the figures against a hazy sky and a landscape just beginning to green and bloom in the spring sun, Lhermitte represents the laborer with genuine empathy. With the advent of machines came a loss of traditional skills and understanding of how to work the land by hand, including digging, sowing, reaping, cutting with a sickle, and tying a sheaf of grain. The mechanization of farming changed the relationship between humanity and nature. Railways connected city and country, offering opportunities for farmers to seek alternative sources of income. They also brought the city into the country in the form of agro-industry and business middlemen.3Yves Lequin, ed., Histoire des Français XIXe–XXe siècles (Paris: Armand Colin, 1983), 85–88, cited in Monica Juneja, “The Peasant in French Painting: Millet to Van Gogh,” Museum International 36, no. 3 (1984): 169. As if to memorialize the way of life of the rural laborer from a time that was quickly disappearing, Lhermitte’s acutely observed works serve as a testament to an era before that cataclysmic change.4The literature concerning the transformation of rural life in the nineteenth century, and on Millet in particular, is extensive. Critical in this dialogue are: T. J. Clark, The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France, 1848–1851 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 72–98; and Raymond Crew, “Picturing the People: Images of the Lower Orders in Nineteenth-Century French Art,” in Art and History: Images and Their Meaning, ed. Robert I. Rotberg and Theodore K. Rabb (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 203–31. See also Richard R. Brettell and Caroline B. Brettell, Painters and Peasants in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Skira/Rizzoli, 1983).

Born in Mont-Saint-Père, a rural farming community approximately sixty-five miles northeast of Paris along the Marne River in the Hauts-de-France region, Lhermitte spent nearly twenty years there observing its customs and ways of life before leaving for Paris in 1863. He displayed an early interest and talent for drawing and enrolled in the École Impériale de Dessin, where he excelled in landscapes of his native town. Lhermitte came of age during a period that not only witnessed a great transformation of agrarian life but also transitioned stylistically from Realism to Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Although he incorporated stylistic elements from all these groups, his work exhibited none of the social protest of Realist painters like Gustave Courbet (1819–77) or Jean-François Millet (1814–75), nor the visionary qualities of avant-garde painters, including Vincent van Gogh (1853–90).5Lhermitte admired Courbet, Millet, and the Barbizon-era artists, and he was invited by Degas to exhibit with the Impressionists in 1879 (he refused), but he regularly exhibited at the annual Salons of Paris. See Monique Le Pelley Fonteny, “Léon Augustin Lhermitte,” in Monique Le Pelley Fonteny, ed., Léon Lhermitte (1844–1925), exh. cat. (Beverly Hills: Galerie Michael, 1989), unpaginated. Instead, as Monique Le Pelley Fonteny suggests, “his scenes were expressive of his time,” bearing the influence of Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), the Barbizon SchoolBarbizon School: A group of French artists, who united around 1830 to form the Barbizon School, which was named after a small village thirty miles northwest of Paris, where they lived and painted. Rebelling against the French Academy’s refined, idealized landscapes, these artists infused the immediacy of the sketches they created outdoors into their finished studio paintings., and Jules Breton (1827–1906)—yet they remain objective, incorporating elements that appealed to public taste. Celebrated for his great powers of observation and insight into the types of people around whom he had grown up, Lhermitte was highly successful during his lifetime.

Those powers of observation come into sharper focus when examining the Nelson-Atkins pastel, a medium the artist had only been using since 1885.6Le Pelley Fonteny, Léon Lhermitte (1844–1925). Lhermitte renders a couple planting potatoes on a small farm, possibly the Ru-Chailly, located across from the Marne from his studio, which served as the site for many of his compositions.7See Monique Le Pelley Fonteny, “Leon-Auguste Lhermitte, Sa Vie, Son Oeuvre: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels, Dessins et Gravures” (PhD diss., Université Paris-Sorbonne, 1989), 37n9. Potato farming was hard work, and when done on a small scale, as seen in the pastel, it was not very profitable. In reality, potatoes were mass-cultivated in northern France from the 1850s. The cooler climate of Mont-Saint-Père, with its average two hundred days of rainfall per year, provides the perfect environment for potato farming. In fact, in France today, production of potatoes is concentrated largely in the Hauts-de-France region, which encompasses Mont-Saint-Père.8Jean-Pierre Goffart et al., “Potato Production in Northwestern Europe (Germany, France, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Belgium): Characteristics, Issues, Challenges and Opportunities,” Potato Research (January 28, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-021-09535-8. See also Eloise Trenda, “The Potato Market in France: Statistics and Facts,” Statistica, October 1, 2021, https://www.statista.com/topics/8051/potato-market-france/#dossierKeyfigures.

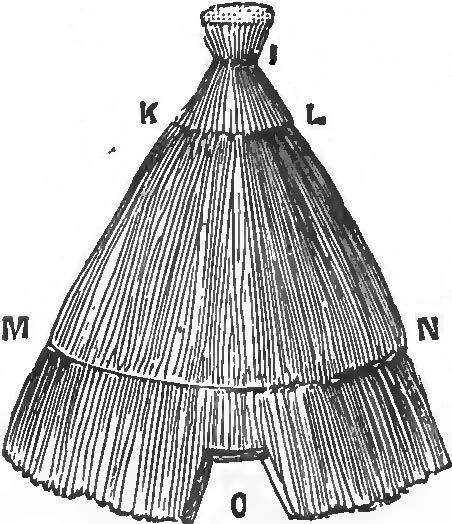

Fig. 4. Léon-Augustin Lhermitte (engraved by Clément Edouard Bellenger), The Potato Harvest from the series Cultivators in the Field, 1885, engraving on paper, 5 x 7 5/8 in. (12.7 x 19.3 cm), published in “Les mois rustiques: Octobre,” Le Monde illustre 29 (November 21, 1885), plate between pp. 344 and 345. CCØ Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet–Histoire de Paris

Fig. 4. Léon-Augustin Lhermitte (engraved by Clément Edouard Bellenger), The Potato Harvest from the series Cultivators in the Field, 1885, engraving on paper, 5 x 7 5/8 in. (12.7 x 19.3 cm), published in “Les mois rustiques: Octobre,” Le Monde illustre 29 (November 21, 1885), plate between pp. 344 and 345. CCØ Paris Musées / Musée Carnavalet–Histoire de Paris

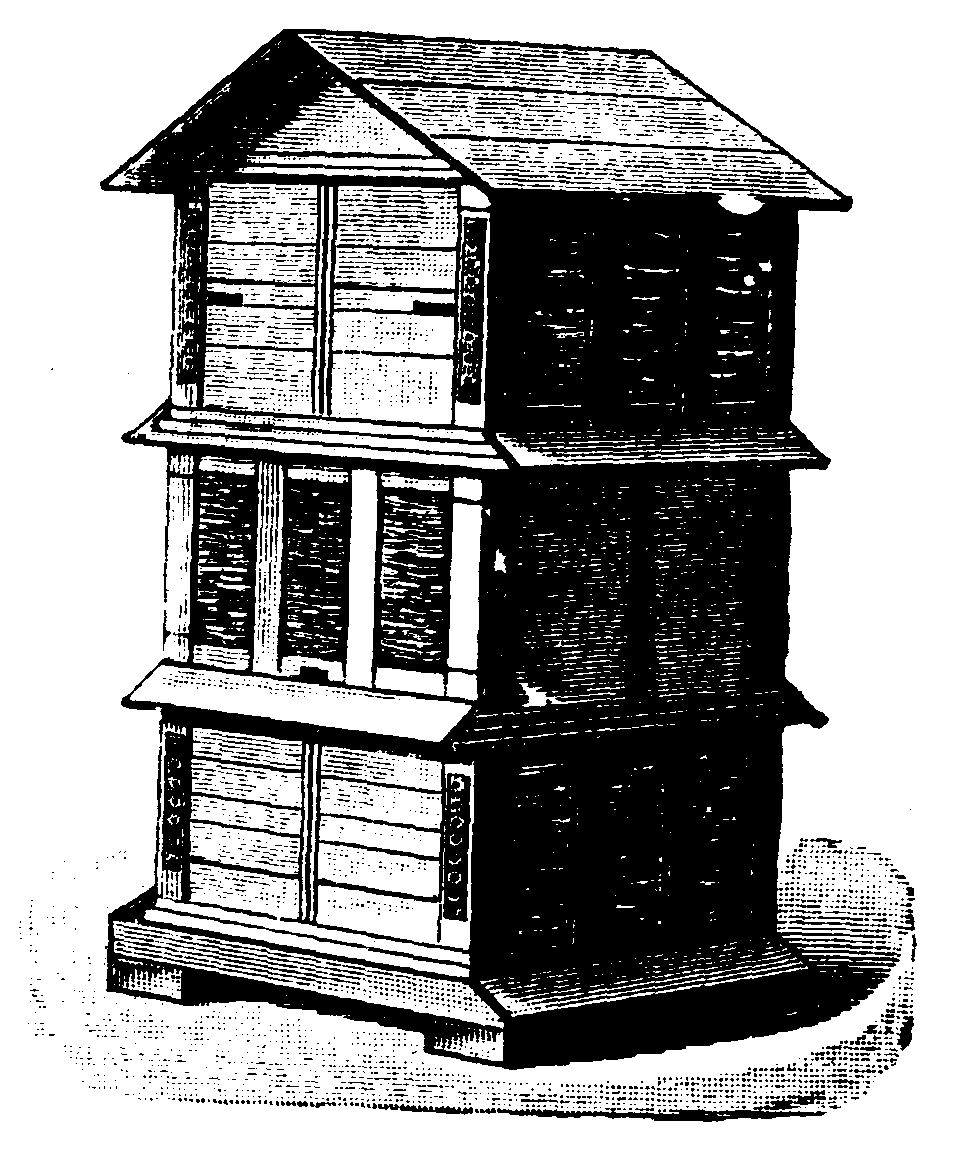

Fig. 5. Jean-François Millet, Potato Planters, ca. 1861, oil on canvas, 32 1/2 x 39 7/8 in. (82.5 x 101.3 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 17.1505. Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Fig. 5. Jean-François Millet, Potato Planters, ca. 1861, oil on canvas, 32 1/2 x 39 7/8 in. (82.5 x 101.3 cm), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 17.1505. Photograph © 2022 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Notes

-

Unless otherwise noted, all translations are the author’s. “Nous avons essayé d’y recueillir pieusement les reliques de ces mœurs, de ces physionomies et de ces paysages qui vont disparaître,—et nous serons largement récompensés de nos eftorts, si nous avons pu ainsi conserver à nos arrière-neveux le tableau d’un monde et d’une nature qu’ils ne connaîtront peut-être plus.” See André Theuriet and Léon Augustin Lhermitte, La vie rustique (Paris: Launette, 1888), viii.

-

An important earlier publication on this subject is Eugene Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: Modernization of Rural France, 1870–1914 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1979).

-

Yves Lequin, ed., Histoire des Français XIXe–XXe siècles (Paris: Armand Colin, 1983), 85–88, cited in Monica Juneja, “The Peasant in French Painting: Millet to Van Gogh,” Museum International 36, no. 3 (1984): 169.

-

The literature concerning the transformation of rural life in the nineteenth century, and on Millet in particular, is extensive. Critical in this dialogue are: T. J. Clark, The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France, 1848–1851 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), 72–98; and Raymond Crew, “Picturing the People: Images of the Lower Orders in Nineteenth-Century French Art,” in Art and History: Images and Their Meaning, ed. Robert I. Rotberg and Theodore K. Rabb (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 203–31. See also Richard R. Brettell and Caroline B. Brettell, Painters and Peasants in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Skira/Rizzoli, 1983).

-

Lhermitte admired Courbet, Millet, and the Barbizon-era artists, and he was invited by Degas to exhibit with the Impressionists in 1879 (he refused), but he regularly exhibited at the annual Salons of Paris. See Monique Le Pelley Fonteny, “Léon Augustin Lhermitte,” in Monique Le Pelley Fonteny, ed., Léon Lhermitte (1844–1925), exh. cat. (Beverly Hills: Galerie Michael, 1989), unpaginated.

-

Le Pelley Fonteny, Léon Lhermitte (1844–1925).

-

See Monique Le Pelley Fonteny, “Leon-Auguste Lhermitte, Sa Vie, Son Oeuvre: Catalogue des Peintures, Pastels, Dessins et Gravures” (PhD diss., Université Paris-Sorbonne, 1989), 37n9.

-

Jean-Pierre Goffart et al., “Potato Production in Northwestern Europe (Germany, France, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Belgium): Characteristics, Issues, Challenges and Opportunities,” Potato Research (January 28, 2022): https://doi.org/10.1007/s11540-021-09535-8. See also Eloise Trenda, “The Potato Market in France: Statistics and Facts,” Statistica, October 1, 2021, https://www.statista.com/topics/8051/potato-market-france/#dossierKeyfigures.

-

Margaret Willes, The Gardens of the British Working Class (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 15.

-

John Hunter, A Manual of Bee-Keeping, 4th ed. (London: W. H. Allen, 1884), 76.

-

Dzierzon’s hive designs built on ideas from Ukranian beekeeper Petro Prokopovych. See M. L. Gornich, “Petro Prokopovich and World Beekeeping,” as reported in Viktor Fursov, “Out of the Past: Petro Prokopovich Remembered; Review of the Scientific Conference, ‘Petro Prokopovich’s Place in the World of Beekeeping,’ January 26, 2013, Kyiv, Ukraine,” Beekeepers Quarterly 3 (March 2013): 49–53.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Nuenen, on or about Monday, March 2, 1885, published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent Van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), https://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let484/letter.html; this request was repeated in another letter from Neunen dated Sunday, June 28, 1855, in Jansen et al., Letters, https://www.vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let510/letter.html.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Antwerp, Saturday, November 28, 1885, in Jansen et al., Letters, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let545/letter.html.

-

Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, The Hague, on or about Thursday, March 29 and Sunday, April 1, 1883, in Jansen et al., Letters, https://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let333/letter.html.

-

See Monica Juneja, “The Peasant in French Painting: Millet to Van Gogh,” 171.

-

Le Pelley Fonteny, Léon Lhermitte (1844–1925).

-

Le Pelley Fonteny, “Leon-Auguste Lhermitte, Sa Vie, Son Oeuvre,” 37n7.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.624.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.624.2088.

Other papers are visible along the edges, and these attest to previous matting campaigns. On all edges, and overlapping onto the back of the strainer and the wooden additions, is a blue paper that was commonly used as a dustcover during nineteenth-century framing campaigns (Fig. 9). A brown laid paper, probably another dust cover, is present along all edges and is peeling away from the upper edge (Fig. 7). Along the right edge is a thick, brown, recycled two-ply paperboard.3Paperboard refers to “stiff and thick ‘paper’ which may range from a ‘card’ of 0.20 mm or 1/125th of an inch or more and vary in composition from pure rag to wood, straw, and other substances having little or no affinity with ‘paper’ beyond the method of manufacture.” See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-making Terms (Amsterdam: N.V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 208–09. Hide gluehide glue: Also called animal skin glue, hide glue is an adhesive produced by boiling the skin, bones, tendons, and other connective tissues of animals to extract collagen proteins. was used as the main adhesive, and patches of the material, on the extreme borders of the artwork, were identified by the bright white ultraviolet (UV) induced visible fluorescence (Fig. 8).

The ground layer is visible in the upper left and right corners of the composition. At upper right, the artist depicted a blue sky, but at upper left, the sky appears unfinished until viewed with the aid of ultraviolet radiation (Fig. 8). This brings out clouds, applied as patches of a white media that mildly absorb the ultraviolet radiation and appear darker than the surrounding ground, which fluoresces yellow. The lowest clouds have a mild pink fluorescence, possibly indicative of carmine.4No efforts, other than visual observation, were undertaken to identify the pigments and dyes used in the pastel media. Carmine is a red colorant derived from cochineal and kermes insects. It produces a vivid pink fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet radiation. It is not lightfast and fades quickly under even the best exhibition standards. See Helmut Schweppe and Heinz Roosen-Runge, “Carmine–Cochineal Carmine and Kermes Carmine” in Artist’s Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, ed. Robert L. Feller (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986), 1:255–83. This suggests that the clouds may have originally had a reddish glow at the time the pastel painting was executed, and raises the question of whether Lhermitte set the scene at sunrise or in the very early evening. Touches of carmine fluorescence can also be seen on the woman’s shoulder and head scarf. Perhaps they reflected the light of the sky? Finally, orange spots of ultraviolet-induced fluorescence are visible in the tree behind the potato garden. Today the pastel strokes in these areas are a dark yellow or colorless and look like leaves, but they may have originally indicated blooms.

Notes

-

The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

There is no documentation that Léon Berville sold primed papers stretched and applied to canvases. However, Lefranc offered pastellists a variety of stretched papers and canvases in rectangular and oval formats, both with or without the inclusion of pumice. Unstretched papers, also in a variety of sizes, were sold with three types of prepared grounds: with pumice, with sand, and smooth. See Lefranc et Cie Catalogue: Fabrique de couleurs et vernis; Toiles à peindre; Carmin, laques, jaunes de chrome de Spooner; Couleurs en tablettes et en pastilles, pastels et généralement tout ce qui concerne la peinture et les arts; Encres noires et de couleurs Pour la Typographie et la Lithographie; Fabrique à Grenelle (Paris: Imprimerie P.-A. Bourdier et Cie, 1862), 40–41.

-

Paperboard refers to “stiff and thick ‘paper’ which may range from a ‘card’ of 0.20 mm or 1/125th of an inch or more and vary in composition from pure rag to wood, straw, and other substances having little or no affinity with ‘paper’ beyond the method of manufacture.” See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-Making Terms (Amsterdam: N.V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 208–09.

-

No efforts, other than visual observation, were undertaken to identify the pigments and dyes used in the pastel media. Carmine is a red colorant derived from cochineal and kermes insects. It produces a vivid pink fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet radiation. It is not lightfast and fades quickly under even the best exhibition standards. See Helmut Schweppe and Heinz Roosen-Runge, “Carmine–Cochineal Carmine and Kermes Carmine” in Artist’s Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, ed. Robert L. Feller (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1986), 1:255–83.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

Probably with the artist until at least April 7, 1898 [1];

With Boussod, Valadon et Cie, Paris, pastel stock no. 14120 [2];

Dr. Schweisguth (probably Charles “Daniel” Schweisguth, [1865–1943]), Paris [3];

Purchased from Dessins, Aquarelles, Gouaches, Pastels, Gravures Par: Barye (A.–L.), Besnard, Boldini, Boudin, Chéret, Cross, Degas, Delacroix, Detaille, Foujita, Frank Will, Guys, Harpignies, Isabey, Jongkind, Laprade, Leloir, Lhermitte, Monnier, Puvis de Chavannes, Stenlein, Vernet, Veyressat, De Waroquier, Willette, Etc; Tableaux Modernes Par: Balfourier, Blanchard, Charlot, Clairin, Delpy (H.–C.), Dufeu, Dupray, Eberl, Fantin–Latour, Favory, Flandrin, Guillaumin, Harpignies, Hébert, Kvapil, Lebasque, Lefebvre, Le Noir, Lotiquet, De Luna, Marchand, Mathey, Méheut, De Neuville, Olive, Picard Ledoux, Pierre, Pigal, Planson, Ribot, Ph. Rousseau, Sabbagh, Valtat, Vollon, Ziem, Etc; Assiette décoré par Vlaminck; Sculptures Par: Carpeaux, Jeanniot, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, March 12, 1941, no. 36, as La plantation des pommes de terre, by André Schoeller on behalf of Gérard frères, March–June 1941 [4];

Purchased from Gérard frères, stock no. 1651, as Plantation p. de terre, by Muller et Clair, Paris, June 20, 1941 [5];

Purchased from Hervé Chassaing, Jacques Rivet et Rémi Fournié, Hôtel des Ventes Saint-Georges, Toulouse, December 15, 1982 [6];

With Galerie du Lethé, Paris, 1982–83;

With Galerie de l’Obsidienne, Paris, 1983;

Private collection, Rhode Island, April 1983;

Private collection, France, by 1987;

Purchased from the latter by Galerie Jacques Bailly, Paris, 1987;

Jane Schnitzer, by 1988 [7];

Purchased from Schnitzer by Altman/Burke Fine Arts, New York, 1988–no later than 1991;

Purchased from Altman/Burke by Samuel Blatt (b. 1942), Boca Raton, FL, by June 2, 1991–2008 [8];

Purchased from Blatt, through Jill Newhouse Gallery, New York, by James W. Sight (b. 1955) and Dr. Heidi A. Harman (b. ca. 1959), Prairie Village, KS, 2008–14;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2014.

Notes

[1] The pastel was lent by the artist to the exhibition, 14ème Exposition de Pastellistes Français, at Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, which opened April 7, 1898. See no. 73.

[2] In 1887, Boussod, Valadon, et Cie signed an exclusive contract with Lhermitte to sell his paintings and pastels. It seems that the stock numbers for pastels were kept separately from those for paintings. See email from Sylvie Brame, Brame et Lorenceau, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, January 14, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] This may be Charles “Daniel” Schweisguth (1865–1943), a Paris doctor who collected pastels and donated several works to the Louvre in 1895. This pastel was not included in the 1924 sale of Schweisguth’s collection.

[4] The inscription next to lot no. 36 in the minutes from the March 12, 1941 sale reads: “Pastel [Schoeller] seize mille / francs”. See “Commisseur-priseur: ADER, Etienne, Minutes, D42E3 185,” Archives de Paris, France.

[5] See email from Magdelaine Dickinson, Wildenstein-Plattner Institute, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, January 14, 2021, NAMA curatorial files. See “Mars–juin 1941, Salesbook of Gérard frères,” Wildenstein-Plattner Institute, New York, where the name “Clair” is listed as the buyer of the Lhermitte. That dealership was originally founded by Georges Muller (b. 1892) at 5, rue La Boétie. Muller, who was Jewish, was forced to sell the gallery on June 7, 1941. Its buyer was his business partner François Clair (1899–1958). The gallery operated under the name Muller et Clair throughout the war, and was registered in the commercial registry of Paris in 1945. We have thus far been unable to confirm when Clair sold the picture. There’s no record of it in the following archive with documentation of Muller et Clair during the war: “Archives de Commissariat Général aux Questions Juives, Dossiers d’Aryanisation des Biens ‘Non Revendiqués’ de la Section VI,” AJ/38/2870, dossier 7425, Archives nationales, Paris.

[6] E. Mayer, International Auction Records (New York: Editions Publisol, 1983), 17:477.

[7] This is possibly Jane Schnitzer (b. 1922, Philadelphia; d. 2015, Fort Lauderdale, FL), who was married to Irving Schnitzer.

[8] A label on the back of the frame states, “Courtesy of Sandy Blatt.” See also the notes from a telephone conversation between Sandy Blatt and Nicole Myers, NAMA, June 19, 2014, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Plantation, 1900, 12 2/3 x 15 3/10 in. (32 x 39 cm), pastel on paper, Galerie Delvaille, Paris.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

Cinquième exposition de la Société de Pastellistes Français, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, April 6–May 6, 1889, unnumbered; Exposition universelle, Champs de Mars (Pavillon spécial), Paris, May 6–October 31, 1889, no. 5, as La plantation des pommes de terre.

14ème Exposition de Pastellistes Français, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, opened April 7, 1898, no. 73, as Plantation de pommes de terre au printemps.

Léon Lhermitte (1844–1925), Galerie Michael, Los Angeles, November 3–December 31, 1989; Altman/Burke Fine Arts, New York, February 22–March 24, 1990, no. 23, as Planting Potatoes.

Revolution in Form: Tampa Collects French Art 1800–1950, Tampa Museum of Art, FL, June 2–August 18, 1991, no. 61, as Potato Planting in the Spring.

Paris 1860–1930: Birthplace of European Modernism, Boca Raton Museum of Art, FL, January 13–March 12, 1999; Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico, March 20–June 15, 2000, unnumbered, as Potato Planting in the Spring.

19th and 20th Century Master Drawings, Jill Newhouse Gallery, New York, July 5–11, 2008, unnumbered, as Potato Planting in the Spring.

Magnificent Gifts for the 75th, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 13–April 4, 2010, no cat., as Potato Planting in the Spring.

From Farm to Table: Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterworks on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 16, 2018–March 17, 2019, no cat., as Potato Planting in the Spring.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Léon-Augustin Lhermitte, Potato Planting in Spring, 1888,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.624.4033.

Catalogue général officiel de l’exposition universelle de 1889 (Lille: Imprimerie L. Danel, 1889), 1:327, as La plantation des pommes de terre.

L. Roger-Milès, “Beaux–Arts: Societé de Pastellistes Français: Cinquiéme Exposition,” L’Evénement, no. 6,221 (April 6, 1889): unpaginated, as la Plantation de pommes de terre.

“Exposition des Pastellistes,” Journal des débats (April 7, 1889): 2, as la Plantation des pommes de terre au printemps.

Charles Frémene, “Les Pastellistes,” Le Rappel, no. 6,967 (April 7, 1889): unpaginated, as Plantation de pommes de terre au printemps.

“Le mouvement artistique,” L’Intérét public (April 9, 1889).

“Mouvement artistique: Exposition des pastellistes,” Le Mot d’ordre, no. 99 (April 9, 1889): unpaginated, as Plantation de pommes de terre au printemps.

Alfred Darcel, “Exposition de la Société des Pastellistes Français,” Journal de Rouen, no. 101 (April 12, 1889): unpaginated.

Desclinville, Journal de l’Aisne (April 17, 1889).

Olivier Merson, “Chronique des Beaux-Arts,” Le Monde Illustré 64, no. 1,673 (April 20, 1889): 262, as Plantation de pommes de terre.

“M. L. Lhermitte à l’Exposition des pastellistes,” Courrier de l’Aisne (April 29–30, 1889), unpaginated, as Plantation de pommes de terre au printemps.

A Record of Art in 1898 (French Section) (London: The Studio, 1898), 14, as Plantation des pommes de terre au printemps.

Catalogue des Dessins, Aquarelles, Gouaches, Pastels, Gravures Par: Barye (A.–L.), Besnard, Boldini, Boudin, Chéret, Cross, Degas, Delacroix, Detaille, Foujita, Frank Will, Guys, Harpignies, Isabey, Jongkind, Laprade, Leloir, Lhermitte, Monnier, Puvis de Chavannes, Stenlein, Vernet, Veyressat, De Waroquier, Willette, Etc; Tableaux Modernes Par: Balfourier, Blanchard, Charlot, Clairin, Delpy (H.–C.), Dufeu, Dupray, Eberl, Fantin–Latour, Favory, Flandrin, Guillaumin, Harpignies, Hébert, Kvapil, Lebasque, Lefebvre, Le Noir, Lotiquet, De Luna, Marchand, Mathey, Méheut, De Neuville, Olive, Picard Ledoux, Pierre, Pigal, Planson, Ribot, Ph. Rousseau, Sabbagh, Valtat, Vollon, Ziem, Etc; Assiette décoré par Vlaminck; Sculptures Par: Carpeaux, Jeanniot (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, March 12, 1941), 7, as La plantation de pommes de terre.

“Á l’hôtel Drouot: Un bronze de Rodin des tableaux et des bijoux,” Le Matin, no. 20,804 (March 14, 1941): 2.

Les ventes de tableaux, aquarelles, gouaches, dessins, miniatures a l’Hotel Drouot, vol. 1, Octobre 1940 à juillet 1941 (Paris: L’Archipel, 1941), 91, as La Plantation des pommes de terre.

Irene Konefal, “Drawings by Millet and Lhermitte in the Johnson Collection,” Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin 75, no. 324 (March 1979): 24.

E. Mayer, International Auction Records (New York: Editions Publisol, 1983): 17:477, as Plantation de pommes de terre.

Possibly Deborah J. Johnson, Rhode Island Collects Paper: Prints, Drawings, and Photographs from Rhode Island Private Collections, exh. cat. (Providence, RI: Rhode Island School of Design, Museum of Art, 1986), unpaginated, as Peasant Family.

Ivo Kirschen, ed., Leon Lhermitte (1844–1925), exh. cat. (Beverly Hills: Galerie Michel, 1989), unpaginated, (repro.), as Planting Potatoes.

Pamela Hammond, “Reviews: Los Angeles—Leon Lhermitte,” ARTnews 89, no. 3 (March 1990): 195, (repro.), as Planting Potatoes.

Ann S. Olson, ed., Revolution in Form: Tampa Collects French Art 1800–1950, exh. cat. (Tampa: Tampa Museum of Art, 1991), 19, 40, (repro.), as Potato Planting in Spring.

Maggie Hall, “Lasting Impressions,” Tampa Tribune, no. 185 (August 3, 1991): (repro.), as Potato Planting in the Spring.

Monique Le Pelley Fonteny, Léon Augustin Lhermitte (1844–1925): catalogue raisonné (Paris: Éditions Cercle d’Art, 1991), no. 26, pp. 167, 506, (repro.), as Plantation de pommes de terre au printemps.

Possibly Joanne Milani, “Shows Reviewed,” Tampa Tribune (September 22, 1995): 17.

Ofir Scheps, Paris 1860–1930: Birthplace of European Modernism, exh. cat. (Boca Raton, FL: Boca Raton Museum of Art, 1999), unpaginated, (repro.), as Potato Planting in the Spring.

Pierre Sanchez, Les Expositions de la Galerie Georges Petit (1881–1934): Repertoire des Artistes et Liste de Leurs Oeuvres (Dijon: L’Echelle de Jacob, 2011), 5:1249, as Plantation de pomme de terre au printemps.

“Jim Sight and Heidi Harman Support Collection,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Winter 2014): 26, (repro.), as Potato Planting in the Spring.