Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.620.5407.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.620.5407.

Edgar Degas began his artistic career in 1853 by studying under professional artists, as was common practice.1His first teacher, in 1853, was Félix Joseph Barrias (1822–1907), and he later studied with Louis Lamothe (1822–69), a pupil of Jean Auguste Dominque Ingres. After a short stint at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris in 1855, he focused on copying European paintings in the collection of the Louvre.2“Degas, Hilaire Germain Edgar,” Bénézit Dictionary of Artists, October 31, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.B00048109. Throughout, he learned the basics of figure drawing and arranging a composition. Jean Auguste Dominque Ingres (1780–1867) was particularly influential to Degas; indeed, Degas was said to “look upon Ingres as the first star in the firmament of French art.”3George Moore, “Degas: The Painter of Modern Life,” Magazine of Art 13 (October 1890): 416–25, cited by Theodore Reff, “‘Three Great Draftsmen’: Ingres, Delacroix, and Daumier,” in Ann Dumas et al., The Private Collection of Edgar Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997), 147. He met Ingres on three occasions and often repeated the advice the elder artist provided: “Study line; draw lots of lines, either from memory or from nature.”4Ann Dumas, “Degas and His Collection,” in Dumas et al., Private Collection of Edgar Degas, 26, 69n128; this is just one of many places where this quote is repeated. Degas first met Ingres on two visits before the 1855 Exposition Universelle and for a third time in 1864, a few years before the elder artist died. Per Dumas, “Degas’s veneration of Ingres was almost cultlike” (26). For the rest of his life, Degas sustained a particular focus on the craft of drawing in graphite, charcoal, and especially pastel. In addition to paintings, monotypes, and wax sculptures, he created thousands of drawings in thirty-eight bound notebooks, on loose sheets of paper, and also as larger-scale works mounted on board. From his roots in academic art, Degas transitioned to his own style that merged older influences with an emphasis on color and mark making over the accuracy of forms. After the Bath is an example of his established style in the mid-1880s; in it, the artist represents a modern woman instead of a classical nude. It was a subject that appealed to collectors in Kansas City and helped to shape the early collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

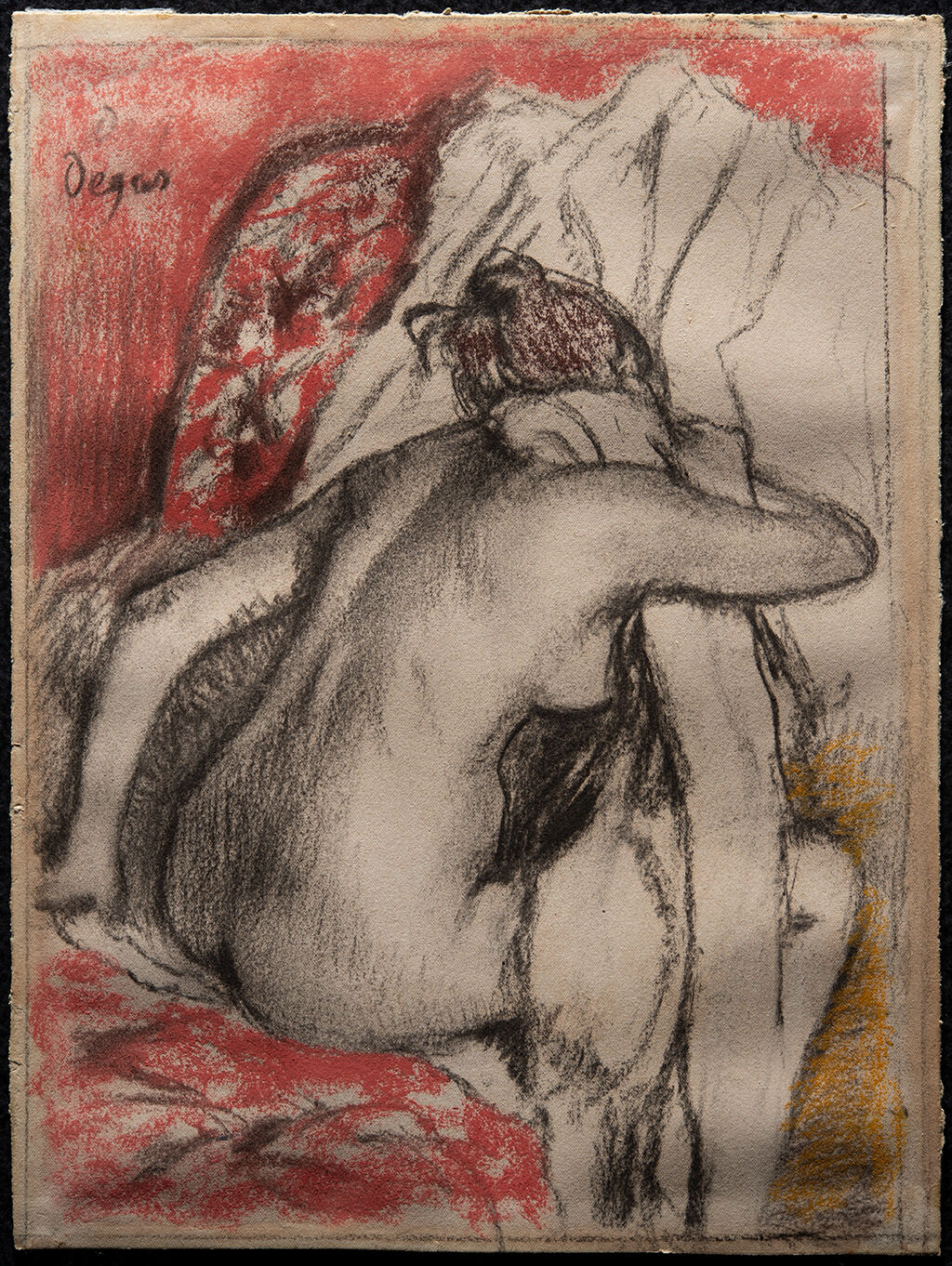

Here, a nude woman sits on a red-patterned slipper chair draped in white fabric. With her back toward the viewer, she leans forward, drying the back of her neck with a towel she holds in her right hand. Wrapped inside the towel, her hand obscures her face from view. She presses her left arm behind her as she balances her body. She appears to brace herself with her legs as she leans forward, but the viewer sees only one rather abnormally elongated right leg, partially concealed by the drapery. Her mahogany-brown hair is piled into a messy topknot. With careful, gestural lines, Degas articulates the folds of the fabric, the indentations of the tufted chair, and the deep shadow near her left arm. Heavy strokes of charcoal deepen the tantalizing outline of the model’s right breast and clinched abdomen. Charcoal shading and reductive erasures describe the muscles and bones of the woman’s back: her spine arches gently in the middle, and her shoulder blades softly reflect the light. This was a modern representation of a woman’s body, not idealized or perfectly balanced like the ones from which Degas had learned. In particular, the leg is not exact to the proportions of a real woman (unless she was especially tall)—but that level of realism was not Degas’s intent. Instead, he sought to describe the essence of the body, the shadow, and the color.

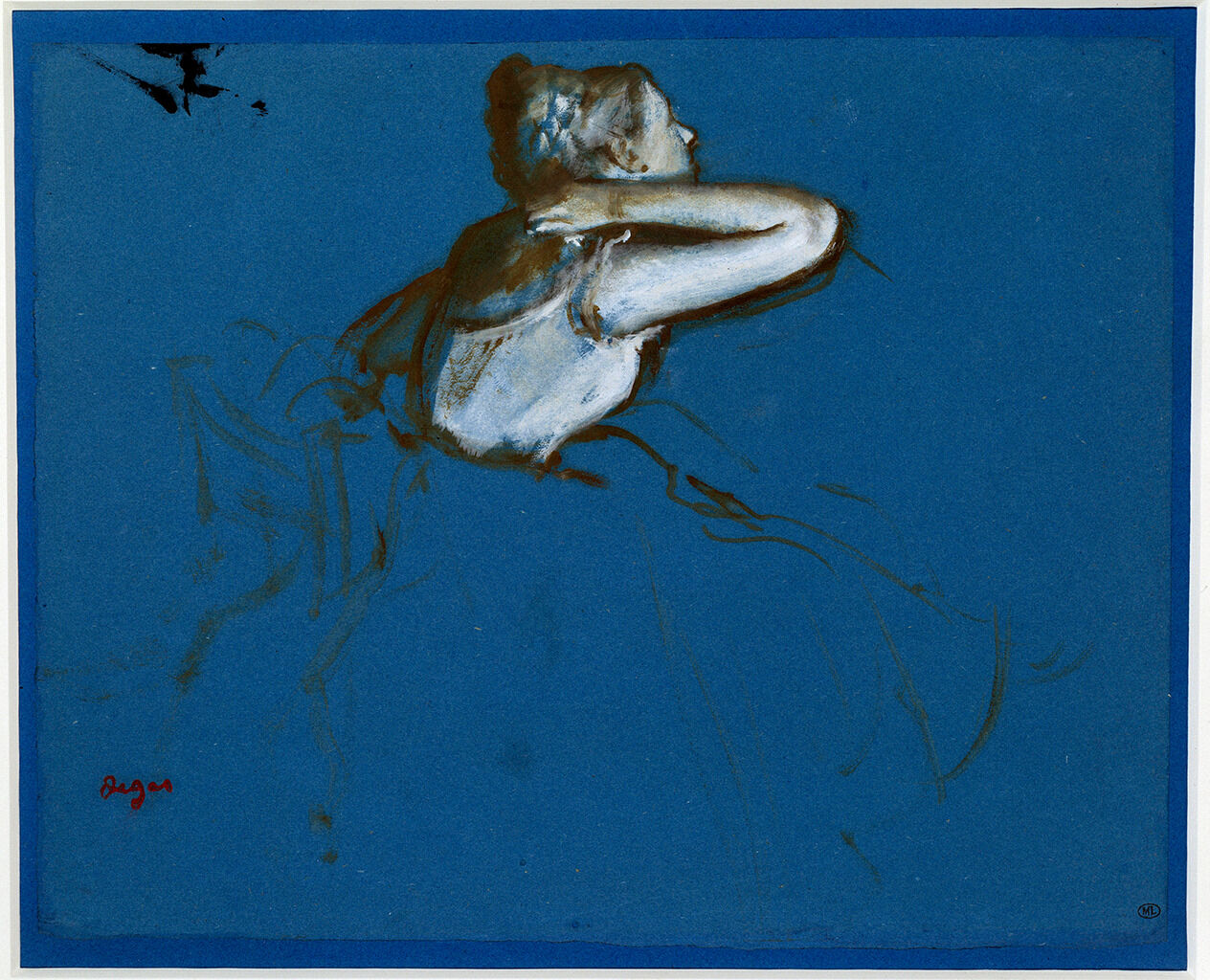

Degas often borrowed poses from earlier works he made from models in his

studio and adapted them for new compositions.5For example, see the related works for Dancer Making Points (ca. 1874–76), https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/impressionism/616/, and Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876), https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/impressionism/614/, in the Nelson-Atkins collection.

In After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself,

he may have been deliberately self-referential. For example, he seems to

have reused his own 1873 study of a seated dancer for this non-ballet

purpose (Fig. 1). The pose of the clothed model in Seated Dancer,

Turned to the Right, leaning forward with her right hand

scratching her neck and her left arm extending behind her, is arguably a

direct source for After the Bath—although Degas lowered the bather’s

right arm from the higher trajectory of the dancer’s. Degas also

repeated the dancer’s pose more straightforwardly in several ballet

works, including two versions of The Rehearsal of the Ballet Onstage

(ca. 1874; both Metropolitan Museum of Art, 29.100.39 and 29.160.26).

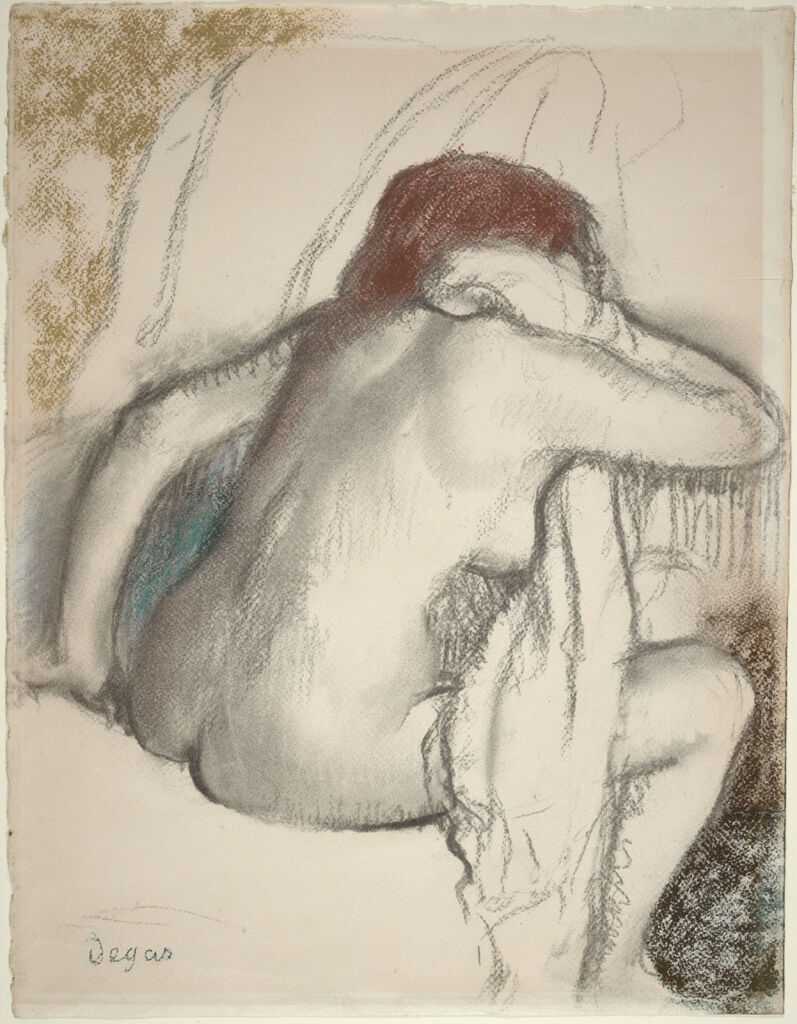

Ingres was a lasting influence on Degas. In addition to copying works by

his role model,6In 1855, Degas visited Ingres’s studio with his family friend Edouard Valpinçon specifically to borrow a painting from the artist for the Exposition Universelle. This is when Ingres first advised Degas to draw lines; see “Degas, Hilaire Germain Edgar.” The painting was Valpinçon Bather (1808; Musée du Louvre, Paris), an example of a nude body disassociated from a narrative and so soft as to appear almost boneless. Degas copied the painting in one of his notebooks that same year; see Degas, carnet 20 (also known in Theodore Reff as Notebook 2), p. 59, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RESERVE 4-DC-327 (D,20), cited in Theodore Reff, The Notebooks of Edgar Degas: A Catalogue of the Thirty-Eight Notebooks in the Bibliothèque Nationale and other Collections (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976), 1:40. Degas also collected many works by Ingres, including

twenty paintings and thirty-four drawings.7Rebecca A. Rabinow, “The Collection Sales: Reviews and Articles,” in Dumas et al., Private Collection of Edgar Degas, 315. In his bedroom on the rue

Victor Massé from at least the early 1890s, Degas displayed (along with

nudes by other artists8Two nudes by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–98) were sold at Degas’s posthumous sale, Tableaux Modernes et Anciens, Aquarelles, Pastels, Dessins . . . composant la Collection Edgar Degas, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, March 26–27, 1918, nos. 236, 237; see also Dumas, “Degas and His Collection,” 16, 33. One of these nudes hung in Degas’s bedroom. Although the drawings are unidentified today, one can imagine Puvis’s strong outline of an idealized, lanky body, with light shading to define muscles, similar to the artist’s other academic nudes and murals for the French state.) Ingres’s study for his mural The Golden

Age (1843–47; Château de Dampierre, France), depicting a seated nude woman. A similar study, although not the one owned by Degas, is today at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Fig. 2). Her back is arched as she leans forward to wrap her arms

around another figure. She turns her head to her left to look at the

viewer with surprise. The way her abdomen is clenched and her belly

slightly protrudes, with her arm raised to reveal small breasts, echoes

the figure in Degas’s After the Bath.

Degas also found inspiration in older examples of nudes that were

considered modern again in the late nineteenth century. He was a

collector of Japanese prints, and a rare and expensive one hung in a

prime place over his bed: Interior of a Bathhouse by Torii Kiyonaga

(Japanese, 1752–1815), an ukiyo-eukiyo-e: Japanese for “pictures of the floating world.” Japanese woodblock prints created by woodblock cutters (sometimes following an artist’s brush drawing) that feature crisp contours and flattened space without much shadowing. diptych created around 1787 (Fig.

3).9Jill DeVonyar and Richard Kendall, Degas and the Art of Japan, exh. cat. (Reading, PA: Reading Public Museum, 2007), 22; and Colta Ives, “Degas, Japanese Prints, and Japonisme,” in Dumas et al., Private Collection of Edgar Degas, 256. Only three impressions are known today (both of the others are first-state impressions: one at the Musée Guimet, Paris, and the other at the Kawasaki Isago no Sato Museum, Japan). In 1893, one impression sold for 5,000 francs, the highest price ever paid in France for an ukiyo-e woodcut. Degas’s diptych hung over his bed in the final decades of his life and was probably there in 1907; Ives, “Degas, Japanese Prints, and Japonisme,” 260n20. Eight elegant young women, in various states of undress, wash or

dry themselves; it may have been because of this extensive display of

nudity that only a handful of prints survived.10Ives, “Degas, Japanese Prints, and Japonisme,” 256. Kiyonaga simplifies

the figures’ forms to unshaded outlines, drawing the viewer’s eye to the

flat patterns in their individualized kimonos. Adding a subtle voyeurism

to the picture, Kiyonaga shows the man who delivers hot water peeking

through a small window at upper left. The naturalism of Kiyonaga’s posed

figures is evident throughout the print: one woman wipes the face of her

struggling toddler son at lower right, and the two nudes at the upper

left turn toward each other, probably chatting, while one lays her hand

gently on the other’s knee. With her back to the viewer and her gluteal

cleft just visible, she turns her head to the right, calling to mind the

woman in After the Bath, with her topknot, extended arm, and

just-visible bottom. The subtle influence of this image and other

Japanese prints on Degas’s art11For a complete study of the influence of Japanese prints on Degas, see DeVonyar and Kendall, Degas and the Art of Japan. For a more one-to-one example of influence, the woman in the black robe in the changing area at lower right may have informed one of Degas’s favorite poses of a ballet dancer adjusting her shoulder strap, for example, Edgar Degas, Dancers (between 1884 and 1885; Musée d’Orsay, Paris), https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/danseuses-129106. contributed to his obsession, from

the 1880s on, with depicting nude women bathing in interior settings,

oblivious to or unconcerned by the viewer watching them.12According to scholar Heather Dawkins, who credits Griselda Pollock for this point, Degas “was the only man to be so intensely involved in repetitiously producing a highly specific range of bather images.” Heather Dawkins, “Frogs, Monkeys and Women: A History of Identifications Across a Phantastic Body,” in Richard Kendall and Griselda Pollock, eds., Dealing with Degas: Representations of Women and The Politics of Vision (New York: Universe, 1992), 204. His women

bend, twist, wash, scratch, and stretch in awkward positions more

indicative of private moments than the nude goddesses of academic easel

painting.

For the eighth Impressionist exhibition in 1886, Degas exhibited what he entitled a “Suite of nude women bathing, washing, drying, wiping, combing or being combed (pastels).”13“Suite de nudes de femmes se baignant, se lavant, se séchant, s’essuyant, se peignant ou se faisant peigner (Pastels).” See 1886: Catalogue de la 8me Exposition de Peinture par Marie Bracquemond, Mary Cassatt, Degas, Forain, Gauguin, Guillaumin, Berthe Morisot, C. Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro, Odilon Redon, Rouart, Schuffenecker, Seurat, Signac, Tillot, Vignon, Zandomeneghi, exh. cat.* *(Paris: Morris père et fils, 1886), 6–7, nos. 19–28. While it is unlikely that the Nelson-Atkins pastel was exhibited as part of this group,14For a list and analysis of the works exhibited, see Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886: Documentation (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), 2:240–41. it is clearly part of his larger series of bathers. The way critics responded to these works is enlightening. They seemed particularly upset by the unflattering angles and ungraceful poses of the women. For example, Félix Fénéon wrote, “these bodies damaged by weddings, childbirth, and illness are dissected or stretched. . . . The lines of this cruel and sagacious observer elucidate, through the difficulties of wildly elliptical shortcuts, the mechanics of all movements; of a being who moves, they not only record the essential gesture, but its most minimal and distant mythological repercussions.”15Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes,” La Vogue 1, no. 10 (June 13–20, 1886): 261–75. “Ces corps talés par les noces, les couches et les maladies, se décortiquent ou s’étirent. . . . Les lignes de ce cruel et sagace observateur élucident, à travers les difficultés de raccourcis follement elliptiques, la mécanique de tous les mouvements; d’un être qui bouge, elles n’enregistrent pas seulement le geste essentiel, mais ses plus minimes et lointaines répercussions mythologiques.”

Gustave Geffroy, who would go on to become an early historian of Impressionism, wrote a lengthy tribute to Degas’s contributions to the exhibition, providing an accurate picture of the artist’s working process: “The man [Degas] is mysterious and taunting . . . [having] the existence of a recluse, locked up with models and sketches. . . . He thus accumulated the materials, piled up an enormous documentation, composed a dictionary of details which would provide, at the first mention, the whole of a decorative work, perhaps the most original, the most personal of this second half of the nineteenth century.”16“L’homme est mystérieux et narquois . . . l’existence d’un reclus, enfermé avec des modèles et des croquis . . . . Il accumule ainsi les matériaux, entasse une énorme documentation, compose un dictionnaire de détails qui fournirait, à la première évocation, l’ensemble d’une œuvre décorative, peut-être la plus originale, la plus personnelle de cette seconde moitié du XIXe siècle.” Gustave Geffroy, “Salon de 1886: VIII. Hors du Salon: Les Impressionnistes,“ La Justice (May 26, 1886): 2. Geffroy goes on to analyze the suite of bathers, pointing out the voyeurism of the poses: “He wanted to paint the woman who does not know she is being looked at, as we would see her, hidden by a curtain, or through a keyhole.”17“Il a voulu peindre la femme qui ne se sait pas regardée, telle qu’on la verrait, caché par un rideau, ou par le trou d’une serrure.” Geffroy, “Salon de 1886, ” 2.

The idea of viewing a nude woman through a keyhole is often repeated in current criticism surrounding Degas, and while the effect is accurate, it seems to disregard the working process that Geffroy acknowledged—that of an obsessive draftsman sketching from models in his studio, repeatedly reworking and reusing poses. The woman pictured in After the Bath assuredly knew of the presence of the artist’s gaze, since she was modeling for Degas in his studio. The wildly patterned and tufted red slipper chair appears in at least seven other works, including Leaving the Bath (ca. 1884; private collection),18See a reproduction at the online digital catalogue raisonné by Michel Schulman: https://www.degas-catalogue.com/la-sortie-du-bain-1057.html?direct=1. See also Nude Woman Kneeling (ca. 1888; private collection), https://www.degas-catalogue.com/femme-nue-agenouillee-597.html?direct=1; Woman Combing Her Hair, (1887–90; private collection), https://www.degas-catalogue.com/femme-se-coiffant-1103.html?direct=1; After the Bath (ca. 1889; private collection), https://www.degas-catalogue.com/apres-le-bain-1025.html?direct=1; Woman at her Toilette (1894; private collection), https://www.degas-catalogue.com/femme-a-la-toilette-1377.html?direct=1; Woman Doing Her Hair (ca. 1894; https://www.degas-catalogue.com/femme-se-coiffant-1708.html?direct=1; and After the Bath (ca. 1895; Courtauld Institute of Art, London, Inv. D.1932.SC.27), https://gallerycollections.courtauld.ac.uk/object-d-1932-sc-27. making it likely that it was a piece of furniture in Degas’s rooms.

As noted, Degas did not depict academic nudes like those of some of his

contemporaries; Jean-Léon Gérôme’s (1824–1904) Moorish Bath (Fig. 4),

from his group of bathing scenes from the 1870s, is a typical

example.19Thank you to my colleague, Brigid Boyle, for suggesting this comparison. Boyle is completing her dissertation for Rutgers University titled “Reckoning with Race: Black Men in Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Orient,” which examines the period reception of Gérôme’s representations of Black soldiers, entertainers, animal handlers, and eunuchs from North Africa and the Ottoman Empire. Gérôme’s painting is meticulously rendered: the women’s

proportions are modeled on classical ideals, and the details of the

architecture and accessories are convincing, making it appear as if the

viewer could enter a real space. Degas’s nudes, on the other hand, are

depicted in awkward positions, usually mid-motion, and in a looser

style. “The four studies from the nude which Degas exhibits are at once

a terror and a delight to behold,” exclaimed George Moore in his review

of the 1886 Impressionist exhibition. “Here we are far from the

slender-hipped nymphs who rise from the sea, or dream in green

landscapes painted in the vicinity of Ville d’Avray.”20[George Moore], “Half-a-Dozen Enthusiasts,” The Bat (London) (May 25, 1886): 185–86. Ville d’Avray was the subject of many sparkling and idyllic landscapes by artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875). For example, see Corot’s nude in The Repose (1860, reworked ca. 1865/1870; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.168845.html. My thanks again to Boyle for her recommendation of this fine example. Instead,

Degas emphasized the reality of a modern, working woman’s figure, with

her curves, the disproportions from an odd viewing angle, and the

realistic task of washing up.

In France, the concept of getting naked, submerging oneself in water (especially warm or hot water), or even touching one’s body was seen as immoral and impractical; this feeling prevailed until at least the early twentieth century.21Steven Zdatny, “The French Hygiene Offensive of the 1950s: A Critical Moment in the History of Manners,” Journal of Modern History 84, no. 4 (December 2012): 899–900. Most households did not have running water or plumbing, and people from all classes and genders tended not to fully bathe. If a full bath was required, pitchers of water would have to be carried from a courtyard fountain, often up a flight of stairs, requiring about thirty trips to fill a tub.22Mary Lynn Stewart, For Health and Beauty: Physical Culture for Frenchwomen, 1880s–1930s (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 66, cited in Zdatny, “French Hygiene Offensive,” 899n5. Beyond the inconvenience, religion and morality warned that the body was “an instrument of sin” and that, if touched too often, it could arouse evil desires.23Zdatny, “French Hygiene Offensive,” 901. Laure Marie Pauline de Broglie, Comtesse de Pange, who was born in 1888, exclaimed in her memoirs, “No one in my family took a bath! The idea of plunging into water up to our necks seemed pagan.”24Comtesse de Pange, Comment j’ai vu 1900 (Paris: B. Grasset, 1962), 86, quoted and translated in Zdatny, “French Hygiene Offensive,” 900. Instead, people limited themselves to washing their faces, hands, and feet. Prostitutes, on the other hand, were required to bathe in a bathtub before each new client.25See Xavier Rey, “The Body Observed,” in George T. M. Shackelford and Xavier Rey, Degas and the Nude, exh. cat. (Boston: MFA Publications, 2011), 99, 102. See also Eunice Lipton, “Degas’s Bathers: The Case for Realism,” Arts Magazine 54 (May 1980): 94–97. Rey also points out that by the late 1870s, the subject of the sex worker was “commonplace in art and literature” (102). Degas created a series of monotypes in the late 1870s of sex workers but did not exhibit them. For an analysis of these works, see Raisa Rexer, “Stocking and Mirrors,” in Jodi Hauptman, ed., Degas: A Strange New Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 137. Nevertheless, in After the Bath, Degas has removed any attributes like a bathtub, stockings, or a bed, which, if included, might indicate she was a sex worker. This could be any woman going about her routine—the subject’s mundanity is a hallmark of Impressionism.

Degas’s dealer Paul Durand-Ruel purchased this pastel about ten years

after its 1885 creation. Perhaps Degas kept After the Bath in his

studio all that time as a template for other works, such as a later,

more quickly executed pastel also titled After the Bath (Fig. 5).26Nelson-Atkins paper conservator Rachel Freeman observed that Degas’s gestural line in the Kansas City work seems more carefully applied than the Cambridge example, which is quickly executed; for more on the construction of the Nelson-Atkins pastel, see her technical entry below. The

Nelson-Atkins After the Bath spent a year in the Paris gallery of

Durand-Ruel until Kansas Citian William Rockhill Nelson (1841–1915) purchased

it in July 1896. According to Jean Sutherland Boggs, Nelson persuaded

Degas (probably through Durand-Ruel) to sign the pastel before his

purchase.27See Jean Sutherland Boggs, Drawings by Degas, exh. cat. (St. Louis: City Art Museum of St. Louis, 1966), 200. It is unclear where this story originated, but according to Bénézit Dictionary of Artists, “He only signed works when he sold or exhibited them”; see “Degas, Hilaire Germain Edgar.” In the upper left corner, a preliminary signature in

charcoal, “Deg,” has been rubbed out and then partially covered in red

pastel; finally the artist added a second, complete signature in

charcoal on top of the red pastel.28See Freeman’s technical entry below.

Nelson was the co-founder (with Mary Atkins, 1836–1911) of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, but in the late 1890s the idea of a museum for Kansas City was only beginning to spark his imagination.29For more about Atkins’s involvement, see Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “The Collecting of French Paintings in Kansas City,” https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/collecting-in-kc/, and Meghan L. Gray and Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Timeline,” https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/timeline/, in this catalogue. After a two-year tour of Europe, including an influential visit to Italy, Nelson decided to bring copies of European old master paintings to Kansas City.30Nelson had already championed structural city improvements, helping to make the city the “Paris of the Plains.” Now he directed his wealth and noblesse oblige toward educating Midwesterners in art, but his interest in elevating Kansas City’s art knowledge was not unusual. It followed a trend starting in 1887 New York with donations by wealthy collectors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See Leanne M. Zalewski, The New York Market for French Art in the Gilded Age, 1867–1893 (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023), 7, 9–10. In February 1897, just a few months after his return from Europe, he opened the Western Gallery of Art, which displayed dozens of painted copies, plaster reproductions, and hundreds of photographs of other works—but none of modern art.31Charles Cowdrick, “The Robust Beginning and the Fateful End of the Western Gallery of Art,” Pitch Weekly, no. 454 (January 23–29, 1997): 11. Although Nelson left Kansas City’s new museum $12 million for the purchase of works of art, his will stipulated that no work could be purchased by an artist who had not been dead at least thirty years.32Nelson’s will allowed for the purchase of reproductions of famous works of art, but the museum quickly decided against that. The museum’s first director, Paul Gardner, had no interest in displaying the Western Gallery’s copies at the newly opened art museum. See Cowdrick, “Robust Beginning,” 12. Instead, most were dispersed to area schools on long-term loan. About two dozen have been returned to the museum or remain there in off-view locations. Interestingly, the Degas pastel was one of five modern pictures owned and displayed in Nelson’s home, Oak Hall.33These included a 1907 portrait of Nelson by William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916), https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/24799/william-rockhill-nelson, whom the museum would not be able to collect, according to Nelson’s will, until 1946; Snow Effect at Argenteuil by Claude Monet (1875; 1840–1926) https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/impressionism/628/, an artist unpurchasable until 1956; Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny, https://nelson-atkins.org/fpc/impressionism/646/ (painted just two years before Nelson acquired it at Durand-Ruel in 1896 and off-limits to the museum until 1933); and an unidentified interior by candlelight by Paul Albert Besnard (1849–1934), an artist the museum would not have been able to purchase until 1964. The Besnard appeared on the same list as the Degas pastel that art advisor R. A. Holland made of Nelson’s objects that he recommended the museum retain. See list attached to letter from Fred C. Vincent, Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trustee, to Herbert V. Jones, NAMA Trustee, December 28, 1927, NAMA curatorial files. Most ultimately came to the museum after Nelson’s family’s deaths in the 1920s,34His wife, Ida, died in 1921, and his daughter and son-in-law died four years later. but the Degas pastel took a circuitous route.

The pastel was initially marked for acquisition by R. A. Holland, art advisor to the Nelson-Atkins trustees, in December 1927, when he reviewed the Nelson family’s collection remaining in Oak Hall.35List attached to Vincent to Jones, December 28, 1927. However, it somehow remained hanging in the Nelsons’ drawing room when the entire contents of the mansion were purchased by Loew’s Incorporated a month later.36“Lump Oak Hall Sale,” Kansas City Star, January 23, 1928. The drawing room contained works primarily featuring women, including unidentified works by Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–92), Portrait of a Woman; Sir William Beechey (British, 1753–1839), Portrait of a Woman; Sir Thomas Lawrence (English, 1769–1830), Portrait of Miss Stack; Gerard (Gerrit) Dou (Dutch, 1613–75), Monk and Angel, on oak panel; Nicholas (Nicolaes) Maes (Dutch, 1634–93), Old Woman Sewing, on oak panel (from Kums collection); and, interestingly, five Japanese prints. No details have been found to identify any of these works. For this list, see “Oak Hall Open Wednesday,” Kansas City Star, October 2, 1927. Herbert Woolf, who was instrumental in founding Midland Theater with Loew’s in downtown Kansas City,37Daniel Coleman, “Herbert M. Woolf: Founder of Woolf Brothers Clothing Store, 1880–1964,” Missouri Valley Special Collections: Biography, 2007, https://kchistory.org/islandora/object/kchistory:115379. invited his sister Gertrude Woolf Lighton to view the Oak Hall collection in 1928, and from it she selected the Degas pastel to keep. Lighton had a vested interest in the city’s nascent museum and particularly in contemporary art; she was one of the founding members of the Friends of Art, a group specifically organized to purchase contemporary art for the Nelson-Atkins and circumvent William Rockhill Nelson’s thirty-year rule.38Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 54–55. The group was founded in December 1934, and barely four months later, the museum’s first director, Paul Gardner, convinced Lighton of the mistake the trustees had made by not keeping the Degas. She graciously agreed to give the pastel to the museum.

Drawing from precedents by Ingres and Kiyonaga, as well as multiple drawings of his own, Degas created After the Bath as a contemporary version of a timeless theme. Through the discerning efforts of important Kansas Citians, the Nelson-Atkins acquired this modern pastel by Degas, one of the first Impressionists and the first work by Degas to enter the collection.

Notes

-

His first teacher, in 1853, was Félix Joseph Barrias (1822–1907), and he later studied with Louis Lamothe (1822–1869), a pupil of Jean Auguste Dominque Ingres.

-

“Degas, Hilaire Germain Edgar,” Bénézit Dictionary of Artists, October 31, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.B00048109.

-

George Moore, “Degas: The Painter of Modern Life,” Magazine of Art 13 (October 1890): 416–25, cited by Theodore Reff, “‘Three Great Draftsmen’: Ingres, Delacroix, and Daumier,” in Ann Dumas et al., The Private Collection of Edgar Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1997), 147.

-

Ann Dumas, “Degas and His Collection,” in Dumas et al., Private Collection of Edgar Degas, 26, 69n128; this is just one of many places where this quote is repeated. Degas first met Ingres on two visits before the 1855 Exposition Universelle and for a third time in 1864, a few years before the elder artist died. Per Dumas, “Degas’s veneration of Ingres was almost cultlike” (26).

-

For example, see the related works for Dancer Making Points (ca. 1874–76) and Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876) in the Nelson-Atkins collection.

-

In 1855, Degas visited Ingres’s studio with his family friend Edouard Valpinçon specifically to borrow a painting from the artist for the Exposition Universelle. This is when Ingres first advised Degas to draw lines; see “Degas, Hilaire Germain Edgar.” The painting was Valpinçon Bather (1808; Musée du Louvre, Paris), an example of a nude body disassociated from a narrative and so soft as to appear almost boneless. Degas copied the painting in one of his notebooks that same year; see Degas, carnet 20 (also known in Theodore Reff as Notebook 2), p. 59, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, RESERVE 4-DC-327 (D,20), cited in Theodore Reff, The Notebooks of Edgar Degas: A Catalogue of the Thirty-Eight Notebooks in the Bibliothèque Nationale and other Collections (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1976), 1:40.

-

Rebecca A. Rabinow, “The Collection Sales: Reviews and Articles,” in Dumas et al., Private Collection of Edgar Degas, 315.

-

Two nudes by Pierre Puvis de Chavannes (1824–98) were sold at Degas’s posthumous sale, Tableaux Modernes et Anciens, Aquarelles, Pastels, Dessins . . . composant la Collection Edgar Degas, Galerie Georges Petit, Paris, March 26–27, 1918, nos. 236, 237; see also Dumas, “Degas and His Collection,” 16, 33. One of these nudes hung in Degas’s bedroom. Although the drawings are unidentified today, one can imagine Puvis’s strong outline of an idealized, lanky body, with light shading to define muscles, similar to the artist’s other academic nudes and murals for the French state.

-

Jill DeVonyar and Richard Kendall, Degas and the Art of Japan, exh. cat. (Reading, PA: Reading Public Museum, 2007), 22; and Colta Ives, “Degas, Japanese Prints, and Japonisme,” in Dumas et al., Private Collection of Edgar Degas, 256. Only three impressions are known today (both of the others are first-state impressions: one at the Musée Guimet, Paris, and the other at the Kawasaki Isago no Sato Museum, Japan). In 1893, one impression sold for 5,000 francs, the highest price ever paid in France for an ukiyo-e woodcut. Degas’s diptych hung over his bed in the final decades of his life and was probably there in 1907; Ives, “Degas, Japanese Prints, and Japonisme,” 260n20.

-

Ives, “Degas, Japanese Prints, and Japonisme,” 256.

-

For a complete study of the influence of Japanese prints on Degas, see DeVonyar and Kendall, Degas and the Art of Japan. For a more one-to-one example of influence, the woman in the black robe in the changing area at lower right may have informed one of Degas’s favorite poses of a ballet dancer adjusting her shoulder strap, for example, Edgar Degas, Dancers (between 1884 and 1885; Musée d’Orsay, Paris), https://www.musee-orsay.fr/en/artworks/danseuses-129106.

-

According to scholar Heather Dawkins, who credits Griselda Pollock for this point, Degas “was the only man to be so intensely involved in repetitiously producing a highly specific range of bather images.” Heather Dawkins, “Frogs, Monkeys and Women: A History of Identifications Across a Phantastic Body,” in Richard Kendall and Griselda Pollock, eds., Dealing with Degas: Representations of Women and The Politics of Vision (New York: Universe, 1992), 204.

-

“Suite de nudes de femmes se baignant, se lavant, se séchant, s’essuyant, se peignant ou se faisant peigner (Pastels).” See 1886: Catalogue de la 8me Exposition de Peinture par Marie Bracquemond, Mary Cassatt, Degas, Forain, Gauguin, Guillaumin, Berthe Morisot, C. Pissarro, Lucien Pissarro, Odilon Redon, Rouart, Schuffenecker, Seurat, Signac, Tillot, Vignon, Zandomeneghi, exh. cat. (Paris: Morris père et fils, 1886), 6–7, nos. 19–28.

-

For a list and analysis of the works exhibited, see Ruth Berson, The New Painting: Impressionism, 1874–1886: Documentation (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1996), 2:240–41.

-

Félix Fénéon, “Les Impressionnistes,” La Vogue 1, no. 10 (June 13–20, 1886): 261–75. “Ces corps talés par les noces, les couches et les maladies, se décortiquent ou s’étirent. . . . Les lignes de ce cruel et sagace observateur élucident, à travers les difficultés de raccourcis follement elliptiques, la mécanique de tous les mouvements; d’un être qui bouge, elles n’enregistrent pas seulement le geste essentiel, mais ses plus minimes et lointaines répercussions mythologiques.”

-

“L’homme est mystérieux et narquois . . . l’existence d’un reclus, enfermé avec des modèles et des croquis . . . . Il accumule ainsi les matériaux, entasse une énorme documentation, compose un dictionnaire de détails qui fournirait, à la première évocation, l’ensemble d’une œuvre décorative, peut-être la plus originale, la plus personnelle de cette seconde moitié du XIXe siècle.” Gustave Geffroy, “Salon de 1886: VIII. Hors du Salon: Les Impressionnistes,” La Justice (May 26, 1886): 2.

-

“Il a voulu peindre la femme qui ne se sait pas regardée, telle qu’on la verrait, caché par un rideau, ou par le trou d’une serrure.” Geffroy, “Salon de 1886, ” 2.

-

See a reproduction at the online digital catalogue raisonné by Michel Schulman: https://www.degas-catalogue.com/la-sortie-du-bain-1057.html?direct=1. See also Nude Woman Kneeling (ca. 1888; private collection), https://www.degas-catalogue.com/femme-nue-agenouillee-597.html?direct=1; Woman Combing Her Hair, (1887–90; private collection), https://www.degas-catalogue.com/femme-se-coiffant-1103.html?direct=1; After the Bath (ca. 1889; private collection), https://www.degas-catalogue.com/apres-le-bain-1025.html?direct=1; Woman at her Toilette (1894; private collection), https://www.degas-catalogue.com/femme-a-la-toilette-1377.html?direct=1; Woman Doing Her Hair (ca. 1894; https://www.degas-catalogue.com/femme-se-coiffant-1708.html?direct=1; and After the Bath (ca. 1895; Courtauld Institute of Art, London, Inv. D.1932.SC.27), https://gallerycollections.courtauld.ac.uk/object-d-1932-sc-27.

-

Thank you to my colleague, Brigid Boyle, for suggesting this comparison. Boyle is completing her dissertation for Rutgers University titled “Reckoning with Race: Black Men in Jean-Léon Gérôme’s Orient,” which examines the period reception of Gérôme’s representations of Black soldiers, entertainers, animal handlers, and eunuchs from North Africa and the Ottoman Empire.

-

[George Moore], “Half-a-Dozen Enthusiasts,” The Bat (London) (May 25, 1886): 185–86. Ville d’Avray was the subject of many sparkling and idyllic landscapes by artist Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875). For example, see Corot’s nude in The Repose (1860, reworked ca. 1865/1870; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.168845.html. My thanks again to Boyle for her recommendation of this fine example.

-

Steven Zdatny, “The French Hygiene Offensive of the 1950s: A Critical Moment in the History of Manners,” Journal of Modern History 84, no. 4 (December 2012): 899–900.

-

Mary Lynn Stewart, For Health and Beauty: Physical Culture for Frenchwomen, 1880s–1930s (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 66, cited in Zdatny, “French Hygiene Offensive,” 899n5.

-

Zdatny, “French Hygiene Offensive,” 901.

-

Comtesse de Pange, Comment j’ai vu 1900 (Paris: B. Grasset, 1962), 86, quoted and translated in Zdatny, “French Hygiene Offensive,” 900.

-

See Xavier Rey, “The Body Observed,” in George T. M. Shackelford and Xavier Rey, Degas and the Nude, exh. cat. (Boston: MFA Publications, 2011), 99, 102. See also Eunice Lipton, “Degas’s Bathers: The Case for Realism,” Arts Magazine 54 (May 1980): 94–97. Rey also points out that by the late 1870s, the subject of the sex worker was “commonplace in art and literature” (102). Degas created a series of monotypes in the late 1870s of sex workers but did not exhibit them. For an analysis of these works, see Raisa Rexer, “Stocking and Mirrors,” in Jodi Hauptman, ed., Degas: A Strange New Beauty, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2016), 137.

-

Nelson-Atkins paper conservator Rachel Freeman observed that Degas’s gestural line in the Kansas City work seems more carefully applied than the Cambridge example, which is quickly executed; for more on the construction of the Nelson-Atkins pastel, see her technical entry below.

-

See Jean Sutherland Boggs, Drawings by Degas, exh. cat. (St. Louis: City Art Museum of St. Louis, 1966), 200. It is unclear where this story originated, but according to Bénézit Dictionary of Artists, “He only signed works when he sold or exhibited them”; see “Degas, Hilaire Germain Edgar.”

-

See Freeman’s technical entry below.

-

For more about Atkins’s involvement, see Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “The Collecting of French Paintings in Kansas City,” and Meghan L. Gray and Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Timeline,” in this catalogue.

-

Nelson had already championed structural city improvements, helping to make the city the “Paris of the Plains.” Now he directed his wealth and noblesse oblige toward educating Midwesterners in art, but his interest in elevating Kansas City’s art knowledge was not unusual. It followed a trend starting in 1887 New York with donations by wealthy collectors to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. See Leanne M. Zalewski, The New York Market for French Art in the Gilded Age, 1867–1893 (New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2023), 7, 9–10.

-

Charles Cowdrick, “The Robust Beginning and the Fateful End of the Western Gallery of Art,” Pitch Weekly, no. 454 (January 23–29, 1997): 11.

-

Nelson’s will allowed for the purchase of reproductions of famous works of art, but the museum quickly decided against that. The museum’s first director, Paul Gardner, had no interest in displaying the Western Gallery’s copies at the newly opened art museum. See Cowdrick, “Robust Beginning,” 12. Instead, most were dispersed to area schools on long-term loan. About two dozen have been returned to the museum or remain there in off-view locations.

-

These included a 1907 portrait of Nelson by William Merritt Chase (American, 1849–1916), whom the museum would not be able to collect, according to Nelson’s will, until 1946; Snow Effect at Argenteuil by Claude Monet (1875; 1840–1926), an artist unpurchasable until 1956; Camille Pissarro, Poplars, Sunset at Eragny (painted just two years before Nelson acquired it at Durand-Ruel in 1896 and off-limits to the museum until 1933); and an unidentified interior by candlelight by Paul Albert Besnard (1849–1934), an artist the museum would not have been able to purchase until 1964. The Besnard appeared on the same list as the Degas pastel that art advisor R. A. Holland made of Nelson’s objects that he recommended the museum retain. See list attached to letter from Fred C. Vincent, Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trustee, to Herbert V. Jones, NAMA Trustee, December 28, 1927, NAMA curatorial files.

-

His wife, Ida, died in 1921, and his daughter and son-in-law died four years later.

-

List attached to Vincent to Jones, December 28, 1927.

-

“Lump Oak Hall Sale,” Kansas City Star, January 23, 1928. The drawing room contained works primarily featuring women, including unidentified works by Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–92), Portrait of a Woman; Sir William Beechey (British, 1753–1839), Portrait of a Woman; Sir Thomas Lawrence (English, 1769–1830), Portrait of Miss Stack; Gerard (Gerrit) Dou (Dutch, 1613–75), Monk and Angel, on oak panel; Nicholas (Nicolaes) Maes (Dutch, 1634–93), Old Woman Sewing, on oak panel (from Kums collection); and, interestingly, five Japanese prints. No details have been found to identify any of these works. For this list, see “Oak Hall Open Wednesday,” Kansas City Star, October 2, 1927.

-

Daniel Coleman, “Herbert M. Woolf: Founder of Woolf Brothers Clothing Store, 1880–1964,” Missouri Valley Special Collections: Biography, 2007, https://kchistory.org/islandora/object/kchistory:115379.

-

Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 54–55.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.620.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.620.2088.

After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself is a quickly completed study of a model in the artist’s studio. Edgar Degas was working out proportion and composition, and he recycled these elements into contemporaneous drawings such as Harvard Art Museums’ After the Bath (see Fig. 5), and later artworks, such as After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself (about 1890–95; National Gallery, London), where the model’s position and the drape of the drying cloth are reversed but closely replicated.

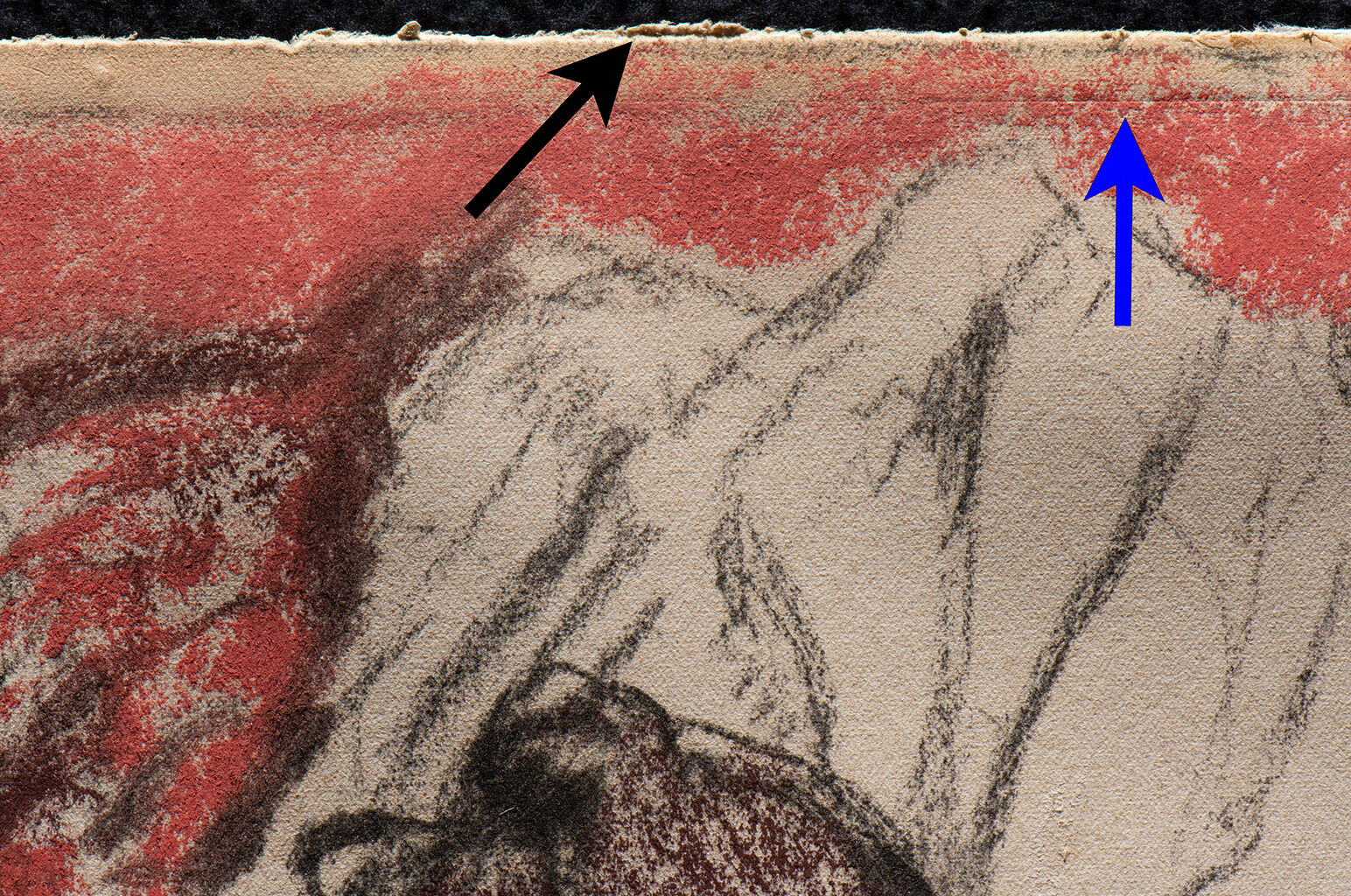

Degas used the screen side of a machine-made, thick, moderately

textured, cream wove paperwove paper: One of the two types of paper. Wove papers may be either machine or handmade, and are produced from molds that have a woven wire mesh. The weave of the mesh can be so tight that it produces no visible pattern within the paper sheet, and often wove papers have a smoother surface than laid papers. Wove papers were developed during the mid-eighteenth century, but did not come into widespread use until later. The other type of paper is laid paper..1The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated. There is no watermarkwatermark: An identifying mark in a paper sheet which is created by tying wires to the papermaking mold. Watermarks are most easily viewed with transmitted light; however, some can be read with raking light. or other evidence

of mill or manufacturer. The overall dimensions are 35.6 x 26.8 cm (14 x

10 1/2 in); however, the paper is a slight trapezoid with the upper, left,

and right edges scored and then torn along a straight edge (Fig. 6). The

lower edge is cleanly cut with a sharp blade. The composition, 34 x 24.8

cm (13 3/8 x 9 3/4 in), is outlined with charcoal. There is another line at right

and upper right that outlines an original, slightly larger composition

size of 34.3 x 25.2 cm (Fig. 7). The media occasionally extends beyond

the lines that indicate the borders.

Fig. 6. Detail of the upper edge at center, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca. 1885). The black arrow indicates an indentation made by a blunt scoring tool and a tag of paper created by tearing against a straight edge. The blue arrow indicates an indented line created by the pressure of a mat from a previous framing campaign.

Fig. 6. Detail of the upper edge at center, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca. 1885). The black arrow indicates an indentation made by a blunt scoring tool and a tag of paper created by tearing against a straight edge. The blue arrow indicates an indented line created by the pressure of a mat from a previous framing campaign.

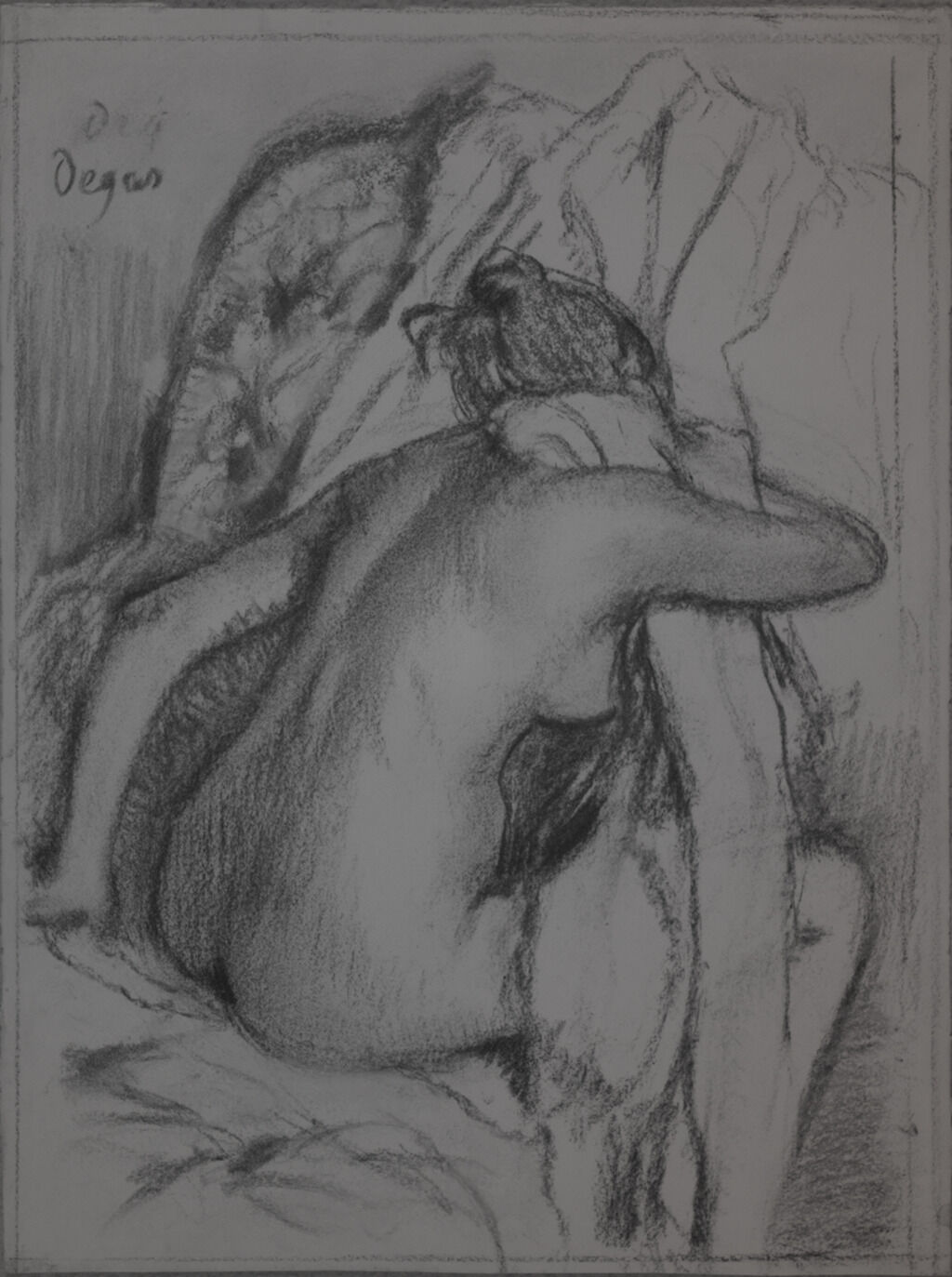

Fig. 7. Reflected infrared digital photograph showing only the charcoal application. The lines that indicate the image area are visible around the perimeter. Also visible in the image is the original higher placement of the model’s right arm and the outlines of her thigh. After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca. 1885)

Fig. 7. Reflected infrared digital photograph showing only the charcoal application. The lines that indicate the image area are visible around the perimeter. Also visible in the image is the original higher placement of the model’s right arm and the outlines of her thigh. After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca. 1885)

The image is executed predominantly in vine charcoalvine or willow charcoal: Long, thin charcoal sticks created by burning grape vines or willow twigs in a low carbon environment. Vine and willow charcoal produce brown to black shades. With magnification, the pastel particles often have a splintered appearance and display a characteristic sparkle., with red, yellow, and magenta pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss. added late in the production process. In addition to working quickly, Degas was economical in his media application, leaving a draped form at upper right and the model’s oddly elongated leg without significant indication of shadows. Degas concentrated his efforts on the model and the folds of the drapery, and he utilized bare paper for lights and highlights. He began with the charcoal outlines of the model and a few strokes to locate the furniture and the draped forms in the background. He adjusted the model’s right arm to a lower position, and, with reflected infrared digital photographyreflected infrared digital photograph: An infrared image produced in the 700–1000 nanometer range, typically captured using an infrared-modified digital camera. See infrared photography., the outlines of the leg are visible though the drying cloth (Fig. 7). Lightly applied and blended hatching defines the contours of the woman’s spine, shoulder blades, hips, and arms. The heavy charcoal lines in the model’s upswept hair are blended. Degas then concentrated on the negative spaces around the sitter. The area between the sitter’s left arm and side, and the quadrangle defined by the breast, drying cloth, thigh, and stomach, are emphasized by heavily applied charcoal. The drapery at extreme left and lower right are lightly shaded with strokes of charcoal.

Color was added as an afterthought, and the same might be said for

Harvard’s After the Bath (Fig. 5), because both the

Kansas City and Harvard pastel paintings feature a cool, dark magenta in

the sitter’s hair. In the Kansas City artwork, yellow appears only over

the light charcoal shading at lower right. Magenta is present in the

hair and blended with the red pastel and charcoal in the draped form at

upper left. Red is the most liberally applied color. Degas used the

pointed end of the red pastel stick in the draped form, and he opted for

the broad side of the stick for the heavy, blended strokes at lower left and along the upper edge.

There is no evidence of fixativefixative: An adhesive or varnish that is applied to the surface of powdery media (pastel, chalk, charcoal, or graphite pencil) to prevent smudging or smearing. Fixatives may be applied during the composition process, so that new layers of media can be added without disturbing the underlayers, or after the artwork is complete. Historic fixatives include natural resins, vegetable gums or starches, animal or fish glues, casein, egg white, and a variety of other materials. In the nineteenth century, cellulose nitrate and other early synthetic polymers were available, and in the twentieth century, acrylics and polyvinyl co-polymers were included in fixative solutions. Until the early twentieth century, when methods for containing pressurized gasses were developed and disposable spray cans became common, the fixative could be spattered over the paper with a brush or applied with an atomizer (also called a blow-pipe or mouth sprayer).. The signature, “Degas,” appears at upper right, in charcoal over the red pastel (Fig. 8). It is directly below an effaced partial signature in charcoal reading “Deg.”

Fig. 9. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph of After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca 1885). The white ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence around the perimeter of the artwork indicates where an adhesive was applied to the verso. Arrows in the lower portion of the image indicate the locations of tidelines that formed during a past conservation treatment that involved gummed linen tape removal.

Fig. 9. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph of After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca 1885). The white ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence around the perimeter of the artwork indicates where an adhesive was applied to the verso. Arrows in the lower portion of the image indicate the locations of tidelines that formed during a past conservation treatment that involved gummed linen tape removal.

Fig. 10. Raking light image of the artwork showing the undulations throughout the center of the sheet and mild contraction of the edges, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca. 1885)

Fig. 10. Raking light image of the artwork showing the undulations throughout the center of the sheet and mild contraction of the edges, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca. 1885)

Notes

-

The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

During the 1980s and 1990s, conservation staff at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art sometimes used Beva Gel (Beva 371 formula, an aqueous dispersion of acrylic and ethylene vinyl acetate resins) as a hinging adhesive for water-sensitive papers or artworks with water-sensitive media. I am indebted to Nancy Heugh for sharing this knowledge with me when discussing possible treatment methodologies. The identification of Beva gel as a hinging adhesive also appears in her 2011 Technical Examination and Treatment Report, NAMA conservation file, 35-39/1.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Preston Hereford with Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

MLA:

Hereford, Preston, with Danielle Hampton Cullen. “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Preston Hereford with Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

MLA:

Hereford, Preston, with Danielle Hampton Cullen. “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

Purchased from the artist by Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock no. 3365, as La sortie du bain, June 29, 1895–July 6, 1896 [1];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel by William Rockhill Nelson (1841–1915), Kansas City, MO, 1896–April 13, 1915;

To his wife, Ida Nelson (née Houston, 1853–1921), Kansas City, MO, 1915–October 6, 1921;

By descent to their daughter, Laura Kirkwood (née Nelson, 1883–1926), Kansas City, MO, 1921–February 27, 1926;

Inherited by her husband, Irwin Kirkwood (1878–1927), Kansas City, MO, 1926–August 29, 1927;

Laura Nelson Kirkwood Residuary Trust, Kansas City, MO, 1927–January 23, 1928 [2];

Purchased from Laura Nelson Kirkwood Residuary Trustees by Loew’s Incorporated, New York, January 23, 1928 [3];

Purchased from Loew’s by Herbert M. Woolf (1880–1964), Kansas City, MO, after January 24, 1928;

Given by Woolf to his sister, Mrs. David M. Lighton (née Gertrude Woolf, ca. 1877–1961), Kansas City, MO, ca. 1928–April 24, 1935;

Her gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1935.

Notes

-

Email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie., Paris, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial file.

-

As early as 1927, art advisor to the NAMA trustees, R. A. Holland, noted the pastel in the contents of Oak Hall, Nelson’s mansion, as one to keep for the budding museum’s collection. Letter from Fred C. Vincent, Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trustee, to Herbert V. Jones, NAMA Trustee, December 28, 1927, NAMA curatorial files. It is unclear why the pastel remained in Oak Hall to be sold to Loew’s.

-

Loew’s bought the entire contents of Oak Hall, where the pastel still hung. A few artworks, though not this pastel, were retained by the museum trustees for the future museum. See “Lump Oak Hall Sale,” Kansas City Star 48, no. 128 (January 23, 1928): 1. Starting the following day, Loew’s resold objects that they could not use to decorate their theater chains. See “A Resale from Oak Hall,” Kansas City Star 48, no. 129 (January 24, 1928): 1.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Preston Hereford with Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

MLA:

Hereford, Preston, with Danielle Hampton Cullen. “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

Same orientation

Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1888, pastel and charcoal on paper, 19 5/8 x 23 3/16 in. (50 x 59 cm), Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux, Le Havre, France, 2004.3.105.

Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1884–86, reworked between 1890 and 1900, pastel on wove paper, 15 7/8 x 12 5/8 in. (40.5 x 32 cm), Musée d’Art Moderne André Malraux, Le Havre, France, 2004.3.106.

Edgar Degas, After the Bath, ca. 1892–94, charcoal and pastel on off-white wove paper, 17 1/8 x 13 1/8 in. (43.5 x 33.2 cm), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA, Inv. 1965.259.

Edgar Degas, Woman Drying Her Hair, ca. 1900–08, pastel on paper, 28 x 24 1/2 in. (71.1 x 62.2 cm), Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA, M.1969.06.P.

Edgar Degas, Woman at her Toilette, 1905–07, charcoal and pastel on tracing paper on cream cardboard, 30 1/4 x 27 1/4 in. (76.8 x 69.3 cm), Cabinet d’arts graphiques des MAH Musées d’Art et Histoire, Geneva, Dépôt de la Fondation Jean-Louis Prevost, 1985-0038.

Reversed orientation

Edgar Degas, Woman at her Toilette, ca. 1884, pastel over monotype on paper mounted on panel, 23 9/16 x 14 15/16 in. (60 x 38 cm), private collection.

Edgar Degas, After the Bath (Exit from the Bath), 1885, pastel, 24 1/4 x 19 3/4 in. (64 x 50 cm), private collection.

Edgar Degas, After the Bath, ca. 1885, charcoal and pastel on white paper 27 x 22 1/4 in. (68.5 x 56.5 cm), private collection.

Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, 1888–92, pastel on paper, 18 15/16 x 24 in. (48.2 x 61 cm), private collection.

Edgar Degas, Woman Drying Herself, 1888–92, pastel, 28 11/16 x 18 7/8 in. (73 x 48 cm), private collection.

Woman Drying Her Hair, ca. 1889, pastel and charcoal on paper mounted on cardboard, 33 1/8 x 41 1/2 in. (84,1 x 105,4 cm), Brooklyn Museum, New York, Inv. 21.113.

Edgar Degas, After the Bath, Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1890–95, pastel on wove paper laid on millboard, 41 3/8 x 39 in. (105 x 99 cm), National Gallery, London, NG6295.

Edgar Degas, After the Bath, ca. 1890–93 (dated in error by another hand: 1885), pastel on paper mounted on cardboard, 26 x 20 3/4 in. (66 x 52.7 cm), Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, CA, F.1975.02.P.

Edgar Degas, Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1896–98, pastel on paper on cardboard, 26 x 24 in. (66 x 61 cm), Foundation E.G. Bührle Collection, Zurich, inv. 33.

Edgar Degas, Nude Woman Drying Her Hair, ca. 1902, pastel on paper on cardboard, 25 1/4 x 27 1/2 in. (64.1 x 69.9 cm), Brooklyn Museum, New York, Inv. 54.54.

Edgar Degas, Woman at her Toilet, ca. 1902, pastel and charcoal on paper, 29 1/8 x 25 9/16 in. (74 x 65 cm), private collection.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Preston Hereford with Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

MLA:

Hereford, Preston, with Danielle Hampton Cullen. “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

Oak Hall Exhibition, Oak Hall, Kansas City, MO, October 5–9, 1927, no cat., as La Sortie du Bain.

Anatomy and Art, William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, MO, May 8–June 5, 1960, no. 60, as Woman Bathing.

Drawings by Degas, City Art Museum of Saint Louis, January 20–February 26, 1967; Philadelphia Museum of Art, March 10–April 30, 1967; The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, May 16–June 25, 1967, no. 132, as Woman Bathing.

Mary Cassatt Among The Impressionists, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, NE, April 10–June 1, 1969, no. 28, as Woman Bathing.

Master Drawings from The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Washington University Gallery of Art, St. Louis, September 22–December 3, 1989; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 17–March 25, 1990, unnumbered, as Woman Bathing, Seen from Behind.

European Drawings from Polish Collections (with additions made from the Nelson-Atkins collection), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 17–June 6, 1993, hors. cat.

Edgar Degas: The Many Dimensions of a Master French Impressionist, Center for the Fine Arts, Miami, FL, April 2–May 15, 1994; Mississippi Museum of Art, Jackson, MS, May 30–July 31, 1994; Dayton Art Institute, August 13–October 9, 1994, no. 14 (Dayton only), as After the Bath, Seated Woman Drying Herself.

Dürer to Matisse: Master Drawings from The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, The Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK, June 23–August 18, 1996; The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens, Jacksonville, FL, September 20–November 29, 1996; The Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH, December 21, 1996–March 2, 1997, no. 74, as After the Bath: Woman Seated Drying Herself.

Color and Line: Masterworks on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, May 5–November 11, 2007, no cat.

Women in Paris, 1850–1900, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 22, 2019–March 22, 2020, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Preston Hereford with Danielle Hampton Cullen, “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

MLA:

Hereford, Preston, with Danielle Hampton Cullen. “Edgar Degas, After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself, ca. 1885,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.620.4403.

“Kansas City,” American Art News 13, no. 30 (May 1, 1915): 5.

“Oak Hall Open Wednesday,” Kansas City Star 48, no. 15 (October 2, 1927): 2A, as La Sortie du Bain.

News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 1, no. 11 (May 12–31, 1935): 2, as Aprés le Bain.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 55, no. 242 (May 17, 1935): 12, as After the Bath.

“Liberal with Art,” Kansas City Star 56, no. 106 (January 1, 1936): 1.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art,” Kansas City Star 99, no. 215 (September 7, 1936): 5, as Woman Bathing.

Agnes Mongan and Paul J. Sachs, Drawings in the Fogg Museum of Art (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1940), 1:363.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts: Founders and Benefactors (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1940), 24, as Woman Bathing.

Winifred Shields, “Degas Works Sold at Auction Are in French Exhibit Here,” Kansas City Star 70, no. 258 (June 2, 1950): 21, as Woman Bathing.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 122, (repro.), as Woman Bathing.

“Anatomy and Art: May 8 to June 5, 1960,” exh. cat., Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 3, no. 1 (1960): 21, as Woman bathing.

Agnes Mongan, Memorial Exhibition: Works of Art from the Collection of Paul J. Sachs [1878–1965], Given and Bequeathed to the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, exh. cat. (1965; Cambridge, MA: Fogg Art Museum, 1971), unpaginated.

Jean Sutherland Boggs, Drawings by Degas, exh. cat. (St. Louis: City Art Museum of St. Louis, 1966), 199–200, (repro.), as Woman Bathing.

“Degas the Draughtsman,” Apollo 85, no. 60 (February 1967): 129, (repro.), as Woman bathing.

William M. Ittman, Jr., “Drawings by Degas,” Master Drawings 5, no. 2 (November 1967): 195–96.

William A. McGonagle, Mary Cassatt Among The Impressionists, exh. cat. (Omaha, NE: Joslyn Art Museum, 1969), 38, 72, (repro.), as Woman Bathing.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 176, 188, (repro.), as Woman Bathing.

Henry C. Haskell, “Gallery Rules and Later Gifts: Nelson Had His Reasons,” Kansas City Star 94, no. 113 (January 13, 1974): E, as Woman Bathing.

Philippe Brame and Theodore Reff, Degas et Son Œuvre, A Supplement (New York: Garland, 1984), no. 114, pp. 124–25, (repro.), as Femme Se Baignant.

“Museums to Sports, KC Has It All,” American Water Works Association Journal 79, no. 4 (April 1987): 133.

Roger Ward and Mark S. Weil, Master Drawings from The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, exh. cat. (St. Louis: Washington University Museum of Art, 1989), 6, 10, 36, (repro.), as Woman Bathing.

Patricia Corbett, “Connoisseur’s World: Power Lines,” Connoisseur 219, no. 934 (November 1989): 44, as Woman Bathing, Seen from Behind.

Donald Hoffmann, “Drawings Tell Ignored Value of Collection,” Kansas City Star 110, no. 135 (February 25, 1990): [1]J, 3J, (repro.), as Woman Bathing, Seen from Behind.

“Special Exhibitions: Master Drawings,” Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (March 1990): (repro.), as After the Bath.

Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 34n1, as After the Bath.

Karen Wilkin, Edgar Degas: The Many Dimensions of a Master French Impressionist, exh. cat. (Dayton, OH: Dayton Art Institute, 1994), 48, 162, (repro.), as After the bath, Seated Woman Drying Herself.

“Music Teachers National Association National Convention, March 23–27, 1996, Kansas City, Missouri,” American Music Teacher 45, no. 4 (February–March 1996): 23.

Roger Ward, Dürer to Matisse: Master Drawings from The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), 10, 30, 225–27, (repro.), as After the Bath: Woman Seated Drying Herself.

Newsletter (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (July 1998): 5, (repro.).

Bill Blankenship, “Drawings from Within,” Topeka Capital-Journal (July 12, 1998): D1, (repro.), as After the Bath: Seated Woman Drying Herself.

Annette Haudiquet, De Delacroix à Marquet: Donation Senn-Foulds, Dessins, exh. cat. (Paris: Somogy éditions d’art, 2011), 198, 200, (repro.), as Après le bain: femme assise s’essuyant.

Michel Schulman, Edgar Degas: The First Digital Catalogue Raisonné, (February 2, 2020): https://www.degas-catalogue.com/apres-le-bain-1210.html, no. MS-1430, (repro), as After the Bath.