![]()

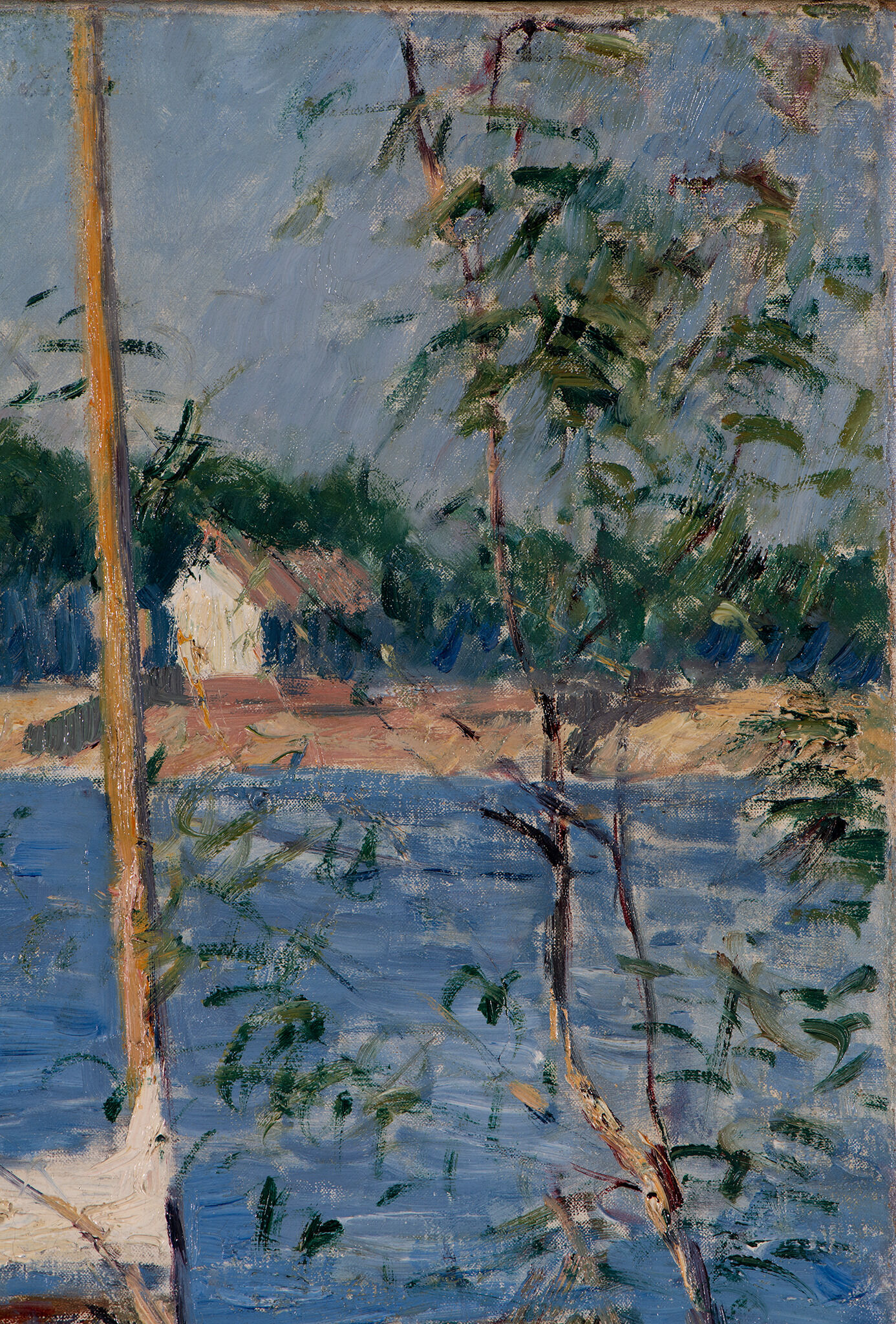

Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891

| Artist | Gustave Caillebotte, French, 1848–94 |

| Title | Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil |

| Object Date | ca. 1886–91 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Bateau au mouillage sur la Seine, à Argenteuil |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 25 3/4 x 21 3/8 in. (65.4 x 54.3 cm) |

| Signature | Signed lower right: Caillebotte |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.5 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.612.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.612.5407.

The epithet “urban Impressionist” has been affixed to Gustave Caillebotte’s (1848–94) name ever since 1995, when the Art Institute of Chicago selected it as the subtitle for their monumental retrospective on the painter.1Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux in association with Abbeville Press, NY, 1995). Co-organized with the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, this international exhibition opened in Paris in 1994 as Gustave Caillebotte, 1848–1894. When the show traveled to Chicago and Los Angeles in 1995, it was rebranded as Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist. The following year, the Royal Academy of Arts, London, mounted a smaller version of the retrospective using the variant title Gustave Caillebotte: The Unknown Impressionist. Caillebotte was born in Paris, maintained an apartment on the ritzy Boulevard Haussmann with his younger brother Martial (1853–1910), and painted many scenes of city life during the first decade of his career, yet this sobriquet arguably mischaracterizes his artistic legacy. After Caillebotte and his brother jointly purchased a riverfront property in Petit Gennevilliers, a town northwest of Paris, in 1881, the artist began retreating from the capital. He would eventually relinquish his Parisian flat in 1887 and settle in Petit Gennevilliers full-time.2Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, Dorothee Hansen, and Gry Hedin, Gustave Caillebotte, exh. cat. (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2008), 16. During this transitional period, Caillebotte’s primary subject matter shifted from bourgeois city-dwellers and urban workers to riverscapes and garden vistas. He produced more than thirty paintings of sailboats in the environs of his suburban home between 1881 and 1893, including Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil. Intended for private enjoyment, these works were never exhibited during Caillebotte’s lifetime.3Gustave Caillebotte, 1848–1894: Voiliers sur la Seine à Argenteuil, 1886 (New York: Simon C. Dickinson, 2016), 7, 24, https://www.simondickinson.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/CAILLEBOTTE.pdf.

The Nelson-Atkins canvas made its public debut in June 1894 at the Galeries Durand-Ruel, four months after Caillebotte’s untimely death.4Also on view was Portrait of Richard Gallo, which Caillebotte had unveiled at the 1882 Impressionist exhibition. Organized in collaboration with the artist’s close friends Claude Monet (1840–1926) and Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), who helped select the paintings and pastels for display, this exhibition was reviewed favorably in the French press.5Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, 24. A critic for Le Petit Parisien pronounced many of Caillebotte’s pictures “masterpieces,” and the Revue du nord journalist Martin Gayant said they showcased “a delightful originality.”6“Échos et nouvelles,” Le Petit Parisien, no. 6482 (June 7, 1894): unpaginated (“Plusieurs sont des chefs-d’œuvre”); Martin Gayant, “Échos du Nord,” La Revue du Nord, no. 13 (July 1, 1894): 32 (“Une savoureuse originalité”). All translations are by the author. Firmin Javal, a commentator for the literary periodical Gil Blas, extolled Caillebotte as “an innovator, a free thinker, a breaker of barriers.”7Firmin Javal, “Les Expositions: G. Caillebotte,” Gil Blas, no. 5316 (June 8, 1894): 3 (“Je trouve en lui un novateur, un affranchi, un briseur d’entraves”). Of particular interest here is a front-page article in La Justice by Gustave Geffroy, an early champion of the Impressionists. Geffroy mentioned Caillebotte’s “passion for boats” and attributed his success in capturing “the precise feeling of [both] the sites around Paris and the banks of rivers and tributaries” to him having one foot in each realm.8Gustave Geffroy, “Notre temps: Gustave Caillebotte,” La Justice, no. 5263 (June 13, 1894): 1. Caillebotte had “la passion des bateaux.” He captured “le sens particulier des sites des environs de Paris et des bords de fleuves et de rivières.” Since Caillebotte divided his time between the city and the countryside, Geffroy reasoned, he understood the middle-class lifestyles of both domains, and that personal sympathy manifested itself in his paintings.

This dual existence dated to Caillebotte’s childhood. When the future artist was twelve years old, his father purchased a riverside estate in Yerres, just south of Paris. Caillebotte and his siblings spent several summers there.9Caillebotte had two younger brothers: Martial, mentioned above, and René (1851–76), who famously appears in Young Man at his Window, 1875, oil on canvas, 46 x 32 in. (117 x 82 cm), private collection. Daniel Charles, a biographer of Caillebotte and authority on French maritime history, speculates that the artist’s well-to-do family possessed a “fleet of pleasure rowing boats” at Yerres.10Daniel Charles, “Caillebotte and Boating,” in Fonsmark, Hansen, and Hedin, Gustave Caillebotte, 111. These youthful experiences on the water proved formative for Caillebotte. They gave rise to several paintings of canotiers, or nonprofessional boatmen, canoeing the Yerres River during the 1870s, and they inspired Caillebotte and his brother Martial to construct their own littoral retreat at Petit Gennevilliers a few years after selling the property at Yerres.11Gustave and Martial Caillebotte sold the Yerres estate in 1879, following the death of their mother on October 20, 1878. Gilles Chardeau, “Caillebotte: A Biographical Chronology,” in Mary Morton and George T. M. Shackelford, Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2015), 236. Once established in this suburb, both men—but especially Gustave—immersed themselves in the world of competitive sailing.

The Nelson-Atkins picture attests to Caillebotte’s zeal for sailing, a hobby that some art historians claim he pursued “to the detriment of his painting.”17For example, Anne Distel, “Introduction: Caillebotte as Painter, Benefactor, and Collector,” in Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, 22. While it is true that Caillebotte devoted significant time and resources to sailing, this pastime also opened up new directions in his artistic production. In the Kansas City canvas, a vessel suited to inland waters is berthed close to the picture plane.18Jean-Louis Lenhof to Brigid M. Boyle, September 5, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. The midday sun casts a brilliant reflection on the water, which Caillebotte rendered with thick strokes of yellow-white paint. Verdant grasses in the foreground counterbalance the smokestack and manufacturing buildings lining the Argenteuil shorefront in the background, creating a fragile equilibrium between nature and industry. Since the mid-1860s, Argenteuil had undergone rapid commercial growth. Town leaders, seeking to establish Argenteuil as a center for trade, welcomed the construction of an iron forge, a sawmill, two chemical plants, distilleries, and several factories.19Tucker, The Impressionists at Argenteuil, 19–21, 38. Caillebotte, like Monet and others who painted in the vicinity of Argenteuil, represented these developments truthfully in his pictures. Argenteuil’s industrial edifices appear in the backgrounds of many paintings, and they are the focus of Caillebotte’s Factories in Argenteuil (Fig. 2), in which half a dozen smokestacks and their reflections anchor the scene. Caillebotte’s pictorial references to the region’s commercial expansion were oddly prescient, for his own estate in Petit Gennevilliers was acquired by the proprietors of a motor works company sixteen years after his death.20Dorothee Hansen, “Impressionist Style: Motifs Along the Seine,” in Fonsmark, Hansen, and Hedin, Gustave Caillebotte, 86–87.

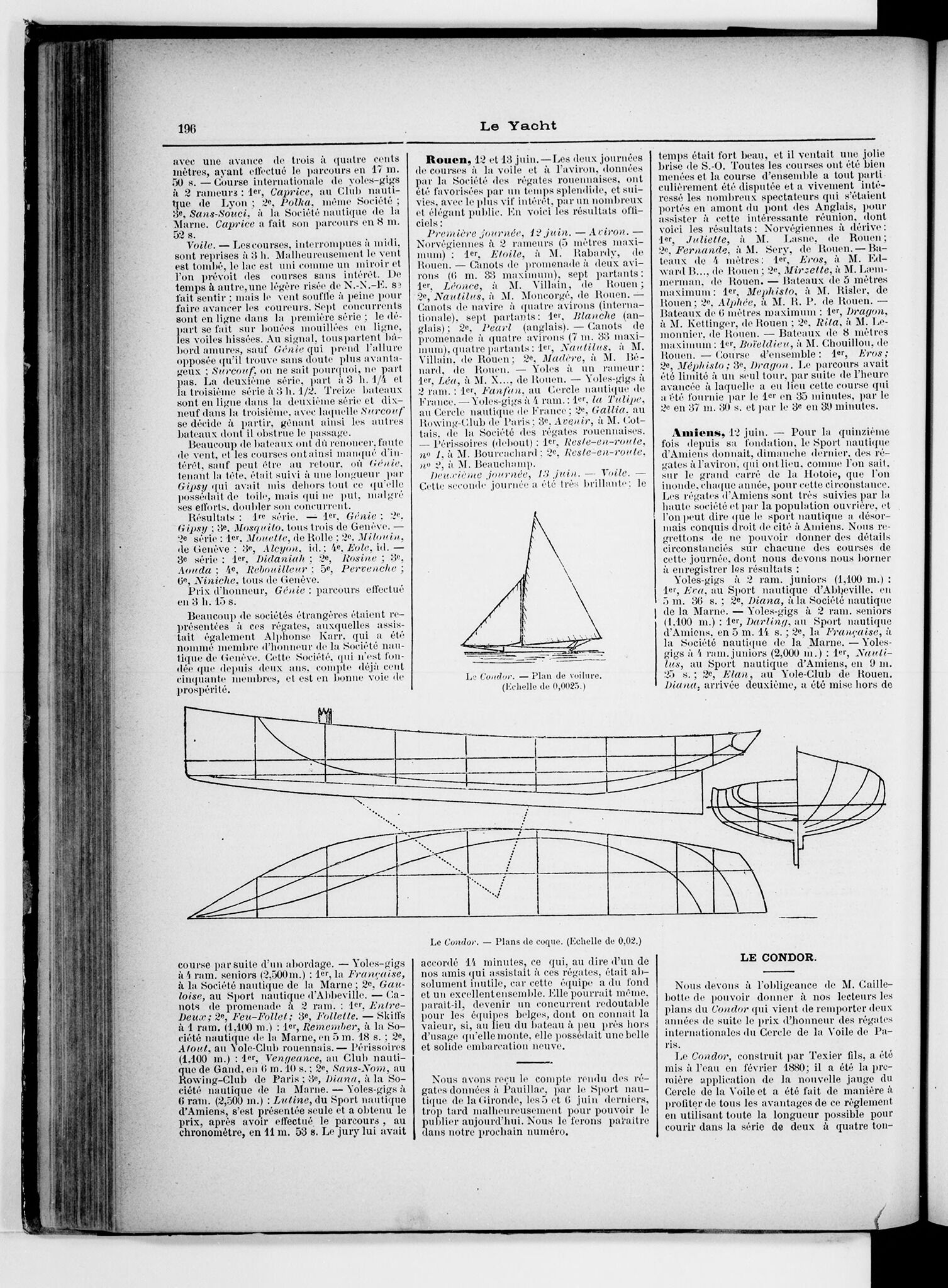

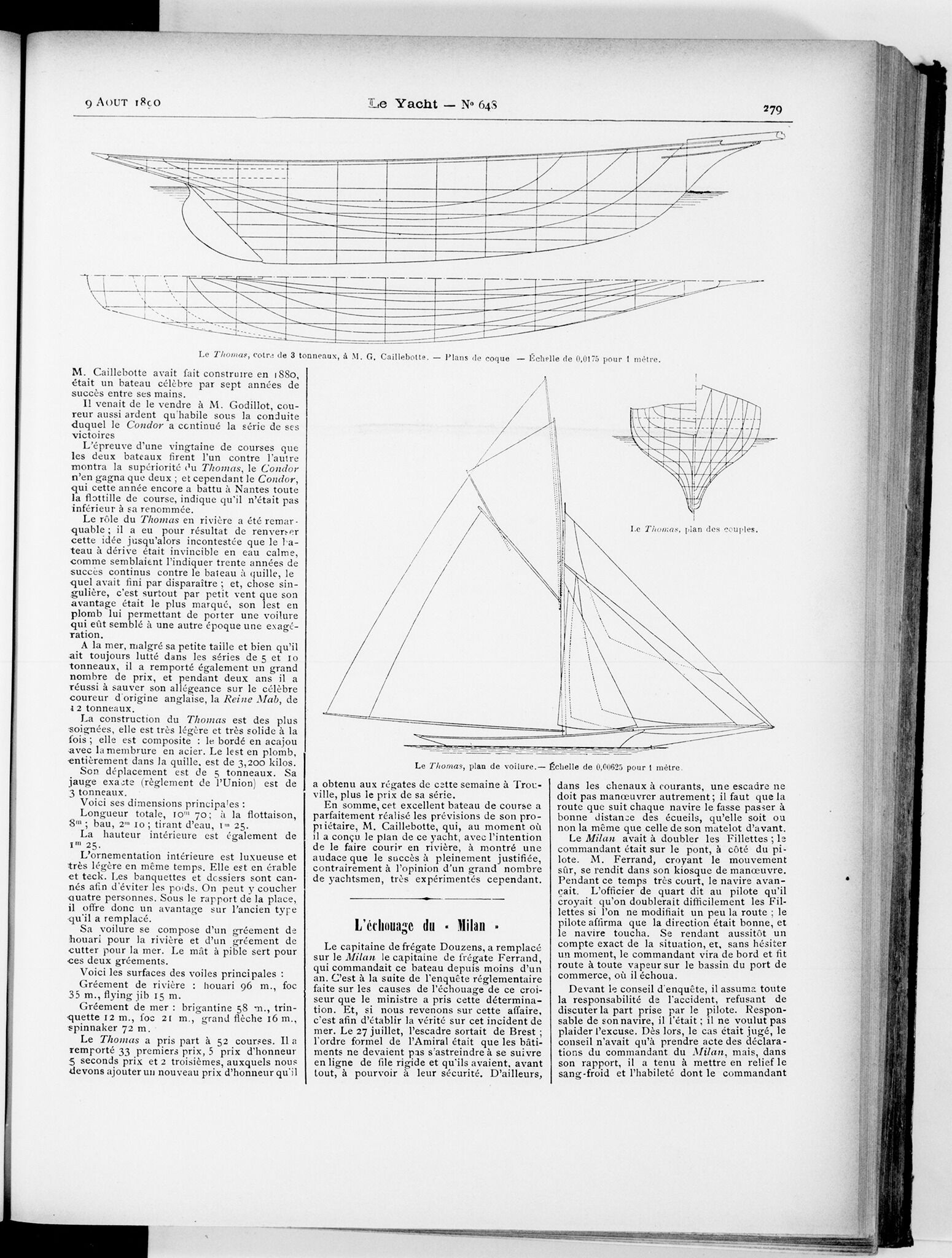

Charles, the aforementioned scholar of French maritime heritage, believes that the vessel in Boat Moored on the Seine is a clipper, a type of dériveurdériveur: sailboat equipped with a centerboard. that dominated French regattas during the 1870s and early 1880s.23Daniel Charles to Brigid M. Boyle, September 6, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. Modeled on American boats known as sandbaggerssandbagger(s): A sailboat that uses sandbags as ballast., clippers were distinguished by their wide, flat hullshull(s): The body or frame of a ship, apart from the masts, sails, and rigging., pivoting iron centerboardscenterboard(s): A retractable board or plate, situated in the midline of the hull of a sailing vessel, that may be lowered or raised to vary the vessel’s lateral resistance and drag or raised for navigation in shallow water., interior ballastsballast(s): Any heavy material, such as gravel, sand, metal, or water, placed in the hold of a ship to weigh it down in the water and prevent it from capsizing when under sail or in motion., long bowspritsbowsprit: A large spar or boom running out from the stem of a vessel, to which the foremast stays (ropes) are fastened., and massive sails. These attributes were ill adapted to the open sea but perfectly tailored to the conditions of the Seine.24Charles, Le mystère Caillebotte, 23; and Trieb, Chevalier, and Casalis, “Impressions de bateaux,” 30. The Seine is known for its feeble winds. When navigating upwind, clippers tackedtacked: To change the course of a vessel by turning its bow into and across the wind; to maneuver a vessel against the wind by a series of tacks. by alternately releasing the jibjib: A triangular sail secured to a stay (rope) forward of the mast or foremast. and mainsailmainsail: The principal sail of a ship., rather than using the rudder to maneuver.25Daniel Charles to Brigid M. Boyle, September 6, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. Although clippers declined in popularity after 1885, some models remained in operation until the 1910s. Caillebotte personally owned and designed several clippers, the most famous of which was the Condor. Outfitted with silk sails, which were exceedingly light and aerodynamic, the Condor won countless prizes at domestic and international competitions.26Trieb, Chevalier, and Casalis, “Impressions de bateaux,” 30. Caillebotte published the plans for its hull and sails in Le Yacht, enabling others to build on his success (Fig. 3).

Caillebotte grew interested in cutters around 1880, when he and engineer Maurice Brault co-designed the Jack. François Chevalier and Jacques Taglang argue that Boat Moored on the Seine depicts this ten-ton, ten-meter-long cutter, the largest sailboat that Caillebotte ever owned.30For the Jack’s plans and dimensions, see Trieb, Chevalier, and Casalis, “Impressions de bateaux,” 38. Daniel Finamore, Russell W. Knight Curator of Maritime Art and History at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA, agrees that the Nelson-Atkins painting portrays a cutter but not the Jack specifically; he posits a smaller vessel. Daniel Finamore to Brigid M. Boyle, September 8, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. Like Charles, they note the absent bowsprit and propose several reasons for its non-appearance. When the Jack first launched on June 4, 1882, it was not armed with a bowsprit; only after the Jack yielded disappointing race results did Caillebotte instruct Texier fils, a shipbuilder in Argenteuil, to add one. Caillebotte may have wished to represent the Jack at this early stage in its evolution. Another possibility is that veracity was not Caillebotte’s primary concern. Had he raised the sails and included the bowsprit, identifying the boat would be a simpler task, but these compositional changes would have obstructed the view of the opposite shore and crowded the right side of the canvas. Caillebotte’s goal, it seems, was not to produce a faithful portrait of the Jack but to record his impressions of a fleeting moment.31For this paragraph, see François Chevalier and Jacques Taglang, Les Impressionnistes et la plaisance (forthcoming in 2022).

Ultimately, both the uncertainty surrounding the date of Boat Moored on the Seine and the artistic license that Caillebotte frequently allowed himself preclude us from definitively identifying the titular vessel. Nevertheless, the above-cited opinions highlight many of the boat’s key features and help to unpack Caillebotte’s creative process. In doing so, they shed light on the final decade of Caillebotte’s career, during which he withdrew from Paris and nurtured his passion for sailing in Petit Gennevilliers, both as a participant and as an observer.

Notes

-

Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux in association with Abbeville Press, NY, 1995). Co-organized with the Galeries Nationales du Grand Palais, this international exhibition opened in Paris in 1994 as Gustave Caillebotte, 1848–1894. When the show traveled to Chicago and Los Angeles in 1995, it was rebranded as Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist. The following year, the Royal Academy of Arts, London, mounted a smaller version of the retrospective using the variant title Gustave Caillebotte: The Unknown Impressionist.

-

Anne-Birgitte Fonsmark, Dorothee Hansen, and Gry Hedin, Gustave Caillebotte, exh. cat. (Ostfildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz, 2008), 16.

-

Gustave Caillebotte, 1848–1894: Voiliers sur la Seine à Argenteuil, 1886 (New York: Simon C. Dickinson, 2016), 7, 24, https://www.simondickinson.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/CAILLEBOTTE.pdf.

-

Also on view was Portrait of Richard Gallo, which Caillebotte had unveiled at the 1882 Impressionist exhibition.

-

Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, 24.

-

“Échos et nouvelles,” Le Petit Parisien, no. 6482 (June 7, 1894): unpaginated (“Plusieurs sont des chefs-d’œuvre”); Martin Gayant, “Échos du Nord,” La Revue du Nord, no. 13 (July 1, 1894): 32 (“Une savoureuse originalité”). All translations are by the author.

-

Firmin Javal, “Les Expositions: G. Caillebotte,” Gil Blas, no. 5316 (June 8, 1894): 3 (“Je trouve en lui un novateur, un affranchi, un briseur d’entraves”).

-

Gustave Geffroy, “Notre temps: Gustave Caillebotte,” La Justice, no. 5263 (June 13, 1894): 1. Caillebotte had “la passion des bateaux.” He captured “le sens particulier des sites des environs de Paris et des bords de fleuves et de rivières.”

-

Caillebotte had two younger brothers: Martial, mentioned above, and René (1851–76), who famously appears in Young Man at his Window, 1875, oil on canvas, 46 x 32 in. (117 x 82 cm), private collection.

-

Daniel Charles, “Caillebotte and Boating,” in Fonsmark, Hansen, and Hedin, Gustave Caillebotte, 111.

-

Gustave and Martial Caillebotte sold the Yerres estate in 1879, following the death of their mother on October 20, 1878. Gilles Chardeau, “Caillebotte: A Biographical Chronology,” in Mary Morton and George T. M. Shackelford, Gustave Caillebotte: The Painter’s Eye, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2015), 236.

-

Paul Hayes Tucker, The Impressionists at Argenteuil, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2000), 14.

-

Bernhard Trieb, François Chevalier, and François Casalis, “Impressions de bateaux: Gustave Caillebotte (1848–1894),” Chasse-marée, no. 116 (May 1998): 29–30. For a map of the Petit Gennevilliers shorefront, see Noëlle Gérôme, “Le quai du Petit-Gennevilliers, de la campagne à la banlieue: La continuité d’un rêve,” in Patrice Bachelard, ed., De Manet à Caillebotte: Les impressionnistes à Gennevilliers (Paris: Éditions Plume, 1993), 78–79.

-

Alfred Sisley (1839–99) taught Caillebotte to sail. See Daniel Charles and Eric Vibart, “L’architecte et son double,” in Bachelard, De Manet à Caillebotte, 91.

-

Caillebotte’s election as vice president was announced in “Communications des sociétés nautiques,” Le Yacht, no. 97 (January 17, 1880): 18.

-

For a chronological list of Caillebotte’s boats, see Daniel Charles, Le mystère Caillebotte: L’Œuvre architecturale de Gustave Caillebotte, peintre impressionniste, jardinier, philatéliste et régatier (Grenoble: Grenat, 1994), 121.

-

For example, Anne Distel, “Introduction: Caillebotte as Painter, Benefactor, and Collector,” in Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, 22.

-

Jean-Louis Lenhof to Brigid M. Boyle, September 5, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Tucker, The Impressionists at Argenteuil, 19–21, 38.

-

Dorothee Hansen, “Impressionist Style: Motifs Along the Seine,” in Fonsmark, Hansen, and Hedin, Gustave Caillebotte, 86–87.

-

See Marie Berhaut, Caillebotte, Sa vie et son œuvre: Catalogue raisonné des peintures et pastels (Paris: Fondation Wildenstein, 1978), no. 360, p. 202; Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte: Catalogue raisonné des peintures et pastels, rev. ed. (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1994), no. 348, p. 203; and Exposition rétrospective d’œuvres de G. Caillebotte, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1894), no. 24, p. 4.

-

See Distel’s entry on no. 109 in Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, 288.

-

Daniel Charles to Brigid M. Boyle, September 6, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Charles, Le mystère Caillebotte, 23; and Trieb, Chevalier, and Casalis, “Impressions de bateaux,” 30. The Seine is known for its feeble winds.

-

Daniel Charles to Brigid M. Boyle, September 6, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Trieb, Chevalier, and Casalis, “Impressions de bateaux,” 30.

-

For this paragraph, see Daniel Charles to Brigid M. Boyle, September 6, 9, and 10, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Jean-Louis Lenhof to Brigid M. Boyle, September 16, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

For another rendering of the Turquoise alongside several other boats, see Le Yacht, no. 274 (June 9, 1883): 191.

-

For the Jack’s plans and dimensions, see Trieb, Chevalier, and Casalis, “Impressions de bateaux,” 38. Daniel Finamore, Russell W. Knight Curator of Maritime Art and History at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, MA, agrees that the Nelson-Atkins painting portrays a cutter but not the Jack specifically; he posits a smaller vessel. Daniel Finamore to Brigid M. Boyle, September 8, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

For this paragraph, see François Chevalier and Jacques Taglang, Les Impressionnistes et la plaisance (forthcoming in 2022).

-

Tentatively, because the Thomas’s bow was more pointed than that seen in the Nelson-Atkins painting. Jean-Louis Lenhof to Brigid M. Boyle, September 5, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Jean-Louis Lenhof to Brigid M. Boyle, September 5, 9, and 16, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Trieb, Chevalier, and Casalis, “Impressions de bateaux,” 33.

-

Jean-Louis Lenhof to Brigid M. Boyle, September 5, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.612.2088

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.612.2088

Painted by Gustave Caillebotte (1848–94), Boat Moored on the Seine exemplifies the artist’s Impressionist style, with expressive brushwork and vibrant colors forming the composition. Executed on plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas, this painting corresponds with a standard-size formatstandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. no. 15 figure.1David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46. The tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. on all four sides remain extant and confirm that the painting’s dimensions have not been altered. A subtle cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. pattern is present on all picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint. perimeter edges and relates to tack holes that are no longer in use.2The canvas is affixed to the stretcher with tacks that were inserted into new holes during a lining that predates the painting’s history at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

The canvas was commercially prepared, with the thinly applied, white or slightly off-white ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. extending to the edges and within the folds of the tacking margins. This ground layer remains visible in many places, such as where the shore and the water meet, around the building roofs, and between skips in the brushstrokes of the water (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Detail of exposed ground in the water and background in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 6. Detail of exposed ground in the water and background in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of underdrawing at the top of the sail in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91). Underdrawing charcoal on top of the ground layer is indicated with a red arrow, while displaced charcoal from the underdrawing is indicated with a yellow arrow.

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of underdrawing at the top of the sail in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91). Underdrawing charcoal on top of the ground layer is indicated with a red arrow, while displaced charcoal from the underdrawing is indicated with a yellow arrow.

Fig. 8. Photograph of underpainting related to the smokestack in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 8. Photograph of underpainting related to the smokestack in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of wet-over-wet brushwork of the grass in the water in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of wet-over-wet brushwork of the grass in the water in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of wet-into-wet brushwork in the boat hull in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of wet-into-wet brushwork in the boat hull in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 11. Detail of the right tree and shore overlapping one another in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 11. Detail of the right tree and shore overlapping one another in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of leaves behind the sailboat mast in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of leaves behind the sailboat mast in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 13. Details of leaves over the water and in the sky in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 13. Details of leaves over the water and in the sky in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 14. Detail of buildings along the shore, formed with short vertical brushstrokes in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 14. Detail of buildings along the shore, formed with short vertical brushstrokes in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 15. Detail of foreground grass and the reflection in the water in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Fig. 15. Detail of foreground grass and the reflection in the water in Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (ca. 1886–91)

Notes

-

David Bomford, Jo Kirby, John Leighton, and Ashok Roy, Art in the Making: Impressionism (London: Yale University Press, 1991), 46.

-

The canvas is affixed to the stretcher with tacks that were inserted into new holes during a lining that predates the painting’s history at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

No drawing was found for the placement of the foreground or trees through microscopy or infrared reflectography.

-

This displacement of underdrawing particles was similarly found in Paris Street; Rainy Day (1877; Art Institute of Chicago). Antoinette Owen, “Cat. 1: Study for ‘Paris Street; Rainy Day,’ 1877: Technical Report,” in Caillebotte Paintings and Drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Gloria Groom and Genevieve Westerby (Art Institute of Chicago, 2015), para 33.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, December 20, 1988, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 2015.13.5.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

Gustave Caillebotte (1848‒1894), Paris and Petit Gennevilliers, France, ca. 1886‒February 21, 1894;

Inherited by his brother, Martial Caillebotte (1853‒1910), February 21‒June 15, 1894;

Purchased from Martial Caillebotte by Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, stock no. 3072, as Bateau à Argenteuil, June 15‒16, 1894 [1];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel by Jean Blum, June 16, 1894‒1967;

Purchased from Blum by Wildenstein and Co., New York, 1967 [2];

Purchased from Wildenstein by George I. Friedland (1901‒1984), Philadelphia, 1967‒1984;

Purchased from his posthumous sale, Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Part 1, Sotheby’s, New York, May 14, 1985, lot 16, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931‒2013) and Henry (1922‒2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1985‒June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel,

Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, to Nicole Myers, Nelson-Atkins, January 11, 2016, NAMA

curatorial files. See also label fixed to backing board verso:

“Dur[an]d-R[uel]/ Paris 16 Rue La[ffit]te/ [Ne]w York 315, Fifth

Avenue/ [Caille]botte No 3[072] / Bateau [Argenteuil ?] / [SS

?]”

[2] See letter from Eliot Rowlands, Wildenstein and Co., New York, to

Meghan L. Gray, Nelson-Atkins, May 12, 2011, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

Gustave Caillebotte, Sailboats on the Seine at Argenteuil, 1886, oil on canvas, 25 9/16 x 21 5/16 in. (65 x 54 cm), private collection.

Gustave Caillebotte, The River Bank at Petit Gennevilliers and the Seine, 1890, oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 50 in. (153 × 127 cm), private collection.

Gustave Caillebotte, Boats on the Seine in Argenteuil, 1890, oil on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 3/4 in. (60 x 73 cm), private collection.

Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Anchored on the Seine, Argenteuil, 1891, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 19 11/16 in. (65 x 50 cm), Château d’Auvers, Collection of the General Council of Val d’Oise, Auvers-sur-Oise, France.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de G. Caillebotte, Galerie Durand-Ruel, Paris, June 1894, no. 24, as Bateau à Argenteuil.

Probably Ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif [Salon d’Automne: Caillebotte Exposition Rétrospective], Grand Palais des Champs-Elysées, Paris, November 1‒December 20, 1921, no. 2734 or 2735, as Bateau.

Rétrospective Gustave Caillebotte au Profit du Musée de Rennes, Galerie des Beaux-Arts, Paris, May 25‒July 25, 1951, no. 68, as Bateaux à Argenteuil.

Gustave Caillebotte, 1848‒1894: a loan exhibition of paintings, Wildenstein and Co., New York, September 18‒October 19, 1968, no. 61, as Le Bateau.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9‒September 9, 2007, no. 13, as Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Megan Seiler, “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

MLA:

Seiler, Megan. “Gustave Caillebotte, Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil, ca. 1886‒1891,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.612.4033.

Exposition Rétrospective d’Œuvres de G. Caillebotte, exh. cat. (Paris: Galeries Durand-Ruel, 1894), 4, as Bateau à Argenteuil.

Probably Société du salon d’automne, Catalogue des ouvrages de peinture, sculpture, dessin, gravure, architecture et art décoratif, exh. cat. (Paris: Société française d’imprimerie, 1921), 335‒36, as Bateau.

Rétrospective Gustave Caillebotte au Profit du Musée de Rennes, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie des Beaux-Arts, 1951), unpaginated insert, Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, MA, as Bateaux à Argenteuil.

Marie Bérhaut, Gustave Caillebotte, 1848‒1894: Catalogue des peintures et pastels (Paris: Wildenstein, 1951), no. 256, unpaginated, as Bateaux à Argenteuil.

A Loan Exhibition of Paintings: Gustave Caillebotte, 1848‒1894, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1968), unpaginated, as Le Bateau.

Marie Berhaut, Caillebotte: The Impressionist, trans. Dana Imber (Lausanne: International Art Book, 1968), 49, (repro.), as The Yacht at Argenteuil.

Marie Berhaut, Caillebotte, Sa Vie et Son Œuvre: Catalogue Raisonné des Peintures et Pastels (Paris: Fondation Wildenstein, 1978), no. 360, pp. 2, 202, (repro.), as Bateau au mouillage sur la Seine, à Argenteuil.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Part 1 (New York: Sotheby’s, May 14, 1985), unpaginated, (repro.), as Bateau au mouillage sur la Seine à Argenteuil.

Patrice Bachelard, ed., De Manet à Caillebotte: Les impressionnistes à Gennevilliers (Paris: Éditions Plume, 1993), 144, as Bateau au mouillage sur la Seine à Argenteuil.

Burl Stiff, “To life! (This one and others!),” San Diego Union-Tribune (June 19, 1994): D-4.

Marie Berhaut, Gustave Caillebotte: catalogue raisonné des peintures et pastels (Paris: Wildenstein Institute, 1994), no. 348, pp. 203, 296, as Bateau au mouillage sur la Seine, à Argenteuil.

Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: 1848‒1894, exh. cat. (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994), 30 [repr., Anne Distel et al., Gustave Caillebotte: Urban Impressionist, exh. cat. (Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1995), 24, 26n49; and repr., Gustave Caillebotte: The Unknown Impressionist, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1996), 22, 24n49].

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 65, (repro.), as Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Sanchez Pierre and Olivier Meslay, Dictionnaire du Salon d’automne: répertoire des exposants et liste des ɶuvres présentées, 1903‒1945 (Dijon: L’Échelle de Jacob, 2006), 271, as Marine.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 12, 74, 78‒81, 158, (repro.), as Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil (Bateau au mouillage sur la Seine, à Argenteuil).

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s Collection of Superb Impressionist Masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

Carol Vogel, “Inside Art: Kansas City Riches,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): https://artdaily.cc/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces#.XoYLQXJ7nIU.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” Architectural Digest blog (August 6, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection, as Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-#.XoYMBnJ7nIU.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016): 80, (repro.).

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

Albert Hect, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go on Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/, (repro.).

David Frese, “A collection of stories: How Henry Bloch acquired the paintings in the new galleries at Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 1D, 4D, (repro.), as Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017), http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article137040948.html [repr., “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum Unveils Bloch Galleries of European Art,” Newtown [CT] Bee (March 10, 2017): 10D, as Boat Moored on the Seine at Argenteuil.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0, (repro.).

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story’,” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): https://www.theartnewspaper.com/news/nelson-atkins-museums-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html, (repro.), as Bateau au mouillage sur la Seine, à Argenteuil.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20‒22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” BlouinArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Erich Hatala Matthes, “Digital replicas are not soulless—they help us engage with art,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (March 23, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/digital-replicas-3d-printing-original-artworks/.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning’,” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview, (repro.).

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/ 2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/Vj42N3pMidFGni38EUajyO/story.html.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Megan McDonough, “Henry Bloch, whose H&R Block became world’s largest tax-services provider, die at 96,” Washington Post (April 23, 2019): https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/henry-bloch-whose-handr-block-became-worlds-largest-tax-services-provider-dies-at-96/2019/04/23/19e95a90-65f8-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922‒2019),” Art Forum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” npr.org (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716661248/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Bloch co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 3A, (repro.).