Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884, and Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884, and Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.606.5407.

It is certainly true that Boudin was surrounded by boats from a young age. His father, Léonard-Sébastien Boudin, came from a long line of seamen and oversaw the steamboat service between Le Havre and Honfleur for over two decades. His mother, Marie-Félicité Boudin (née Buffet), served as a chambermaid aboard various ships. Boudin himself worked as a mousse (sailor’s apprentice) beginning at age ten.4Georges Jean-Aubry, Eugène Boudin d’après des documents inédits: L’Homme et l’œuvre (Paris: Editions Bernheim-Jeune, 1922), 17–19. However, when Boudin took up painting in 1847, he did not immediately gravitate toward maritime subjects. Instead, he tried his hand at portraiture and still lifes, depicted Breton religious ceremonies known as pardons, and, above all, captured the bourgeois beachgoers at Trouville and Deauville.5Boudin later claimed to have abandoned portraiture because the vogue for daguerreotypes reduced the demand for painted portraits. See Paul Leroi, “Salon de 1887 (suite),” L’Art: Revue bimensuelle illustrée, no. 556 (July 15, 1887): 32. Boating scenes remained a marginal portion of Boudin’s production during the 1850s and 1860s. It was only in 1869, as Laurent Manœuvre has noted, when Belgian dealer Léon Gauchez commissioned Boudin to paint several maritime pictures, that the artist turned his attention in earnest to the sea in the hope of building an international clientele.6Laurent Manœuvre, “Eugène Boudin, Gustave Courbet et le développement de l’impressionnisme,” in Frédérique Thomas-Maurin, Julie Delmas, and Élise Boudon, eds., Courbet et l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Milan: Silvana, 2016), 44–45. According to a letter dated August 30, 1869, from Boudin to his friend Ferdinand Martin, Gauchez intended to market Boudin’s maritime scenes to collectors of Belgian seascapes, a strategy he had already employed for paintings by Johan Barthold Jongkind. As Boudin continued in this genre, his seascapes also attracted French tourists, who were vacationing at the shore in ever-greater numbers.

The Boudin harbor scenes at the Nelson-Atkins both portray Deauville, a fashionable resort town for the beau monde (high society) of Paris. Once a quiet hamlet known primarily for its fish market and thatched roofs, Deauville was redeveloped in the 1860s by Charles-Auguste-Louis-Joseph, duke de Morny, who built a racetrack, casino, and railway station to lure the upper classes.7See Anna Bowman Dodd, Up the Seine to the Battlefields (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1920), 34–36; and Suzanne Cassidy, “The Thoroughbred Called Deauville,” New York Times, July 23, 1989. Some scholars argue that the duke’s role in transforming Deauville has been overstated; see Frédérique Citéra, “Deauville,” in Un siècle de bains de mer dans l’estuaire de la Seine, 1830–1930, exh. cat. (Honfleur: Musée Eugene Boudin, 2003), 36–39. Boudin witnessed these changes firsthand, attending the inaugural horse races at the hippodrome and the opening concerts at the casino. A regular visitor to Deauville during July and August, he built himself a Neo-Norman–style summer residence on the rue Olliffe in 1884, when he had at last achieved some material success.8Carla Gottlieb, “Boudin’s Drawings,” Master Drawings 6, no. 4 (Winter 1968): 401. Boudin lived in relative poverty for much of his life. It was not until the early 1880s, when Durand-Ruel took notice of his work, that Boudin became financially secure. During Boudin’s final two decades, he painted Deauville’s busy harbor incessantly, determined to preserve “the appearance, riggings, and state of our ports in our age.”9Leroi, “Salon de 1887 (suite),” 33. “L’allure, les gréements et l’état de nos ports à notre époque.” Leroi quotes from a letter by Boudin to a mutual friend. After Boudin was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1895, he moved to Deauville full time to live out his remaining years in his favorite seaside locale. He became so associated with the town that when Deauville celebrated its 150th anniversary in 2010, it designated August 8 “Eugène Boudin Day” in honor of its most famous former resident.10See “Normandy Impressionist Festival,” Times (London), April 24, 2010; and Seth Sherwood, “On the Cote Fleurie,” New York Times, August 8, 2010.

While the majority of Boudin’s Deauville harbor scenes document the routine comings and goings of sailboats, a few portray those crafts outfitted for special occasions. Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville is one such picture. Painted in August 1895, most likely on the sixth day of a regatta (as discussed below), it features half a dozen vessels whose assorted pennants wave jauntily in the breeze. Yacht races were part of a burgeoning leisure culture for the European well-to-do. Beginning in the 1850s, French plaisanciers (pleasure boaters) participated in sailing contests at popular seaside resorts in imitation of their British peers, who already had a well-established tradition of regattas on the River Thames. Most did not pilot their vessels themselves, instead hiring professional sailors to staff them.16Jean-Louis Lenhof, “Régates et navigation de plaisance en baie de Seine au XIXe siècle,” in Dominique Barjot, Eric Anceau, and Nicolas Stoskopf, eds., Morny et l’invention de Deauville (Paris: Armand Colin, 2010), 381–406. As Lenhof explains, yachting took two forms in nineteenth-century France: yachting de croisière and yachting de course, or cruising and racing. When used as cruise ships, yachts were essentially “traveling private mansions” that allowed their owners to sightsee while still enjoying the comforts of home. They offered a novel place to entertain guests and conduct business. When used as racing vessels, yachts were equally luxurious but differently equipped: they did not rely on steam propulsion, and their sails could adapt more easily to variable winds. The Cercle de la Voile de Paris, a prominent yacht club founded in the French capital in 1858, collaborated with regional associations to organize annual events that became important fixtures on the summer social calendar.17For example, in 1892 the Cercle de la Voile de Paris joined forces with a company in Trouville to host a three-day regatta in late July. See Henri Philippe, “Yachting-Gazette: Revue des régates à la voile en 1892,” Le Sport, no. 18 (March 3, 1893): 284–85.

Boudin’s interest in yachting and seaside galas dates to early in his career, as evidenced by Festival in the Harbor of Honfleur of 1858 (Fig. 5). Painted in the artist’s hometown, this seascape captures the joy of summertime and the excitement of a swimming competition. Men in bathing caps race to shore, watched by some nearby mallards and numerous spectators crammed into rowboats. Overhead, pennants flutter merrily in the wind and cast colorful shadows on the water. Though the subject is similar to that of Boats Decorated with Flags, the handling is much more meticulous. The intricate mesh of ropes required to operate the trois-mâts (three-masted ship) is painstakingly delineated, almost as if Boudin used a straightedge, and the rowboat passengers are distinguished from one another by their clothing and umbrellas. By contrast, the Nelson-Atkins panel is freer and more confident in its execution. Boudin painted most of the flags in three strokes or fewer, and he condensed the oarsmen to a few dots of pigment, imbuing the Kansas City picture with a greater sense of immediacy than its predecessor.

Fig. 5. Eugène Boudin, Festival in the Harbor of Honfleur, 1858, oil on panel, 16 1/8 x 23 3/8 in (41 x 59.4 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Fig. 5. Eugène Boudin, Festival in the Harbor of Honfleur, 1858, oil on panel, 16 1/8 x 23 3/8 in (41 x 59.4 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon

Fig. 6. Eugène Boudin, Study of Flags Raised on a Ship, undated, black chalk and pastel on yellow paper, 6 x 7 11/16 in. (15.3 x 19.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF16793-recto. Photo: Thierry Le Mage © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 6. Eugène Boudin, Study of Flags Raised on a Ship, undated, black chalk and pastel on yellow paper, 6 x 7 11/16 in. (15.3 x 19.5 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF16793-recto. Photo: Thierry Le Mage © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Like other paintings in Boudin’s vast oeuvre, Boat Decorated with Flags is inscribed with the city, month, and year of its creation: “Deauville Aout 95.” Though this date is already quite precise, new information may allow us to pinpoint the exact day on which Boudin painted the seascape. On August 20, 1895, French journalist Jehan Soudan de Pierrefitte published a detailed account of a weeklong celebration in Deauville. On the fifth evening of the festival, yachts bedecked with Bengal lightsBengal lights: A firework or flare with a steady blue light, used, especially formerly, as a signal. paraded through the harbor, treating revelers to a stunning display that remained illuminated until daybreak. The following morning, August 19, people took strolls along the beachfront, admiring “the cheerful pennants and flags floating before the row of red parasols.”20Jehan Soudan [de Pierrefitte], “À Trouville,” Le Journal, no. 1057 (August 20, 1895): 2. “Les gais pavillons et drapeaux flottants devant les rangs de parasols rouges.” Some lunched al fresco on the casino’s terrace and then caught an opera matinee. That afternoon, large crowds enjoyed a regatta organized by Count Jean Alfred Octave de Chabannes la Palice, a French sailor and nobleman who later represented France at the 1900 Olympics in Paris. Many also amused themselves by watching the duck races, hog contests, and swimming competitions.

While those sporting events were taking place, Soudan de Pierrefitte happened upon “the master E. Boudin, painting this aquatic fair from the quay; the painter Jules Lefebvre, a habitué of Benerville-sur-Mer, [was] also there.”21Soudan [de Pierrefitte], “À Trouville,” 2. “Surpris le maître E. Boudin, peignant du quai cette kermesse aquatique; le peintre Jules Lefebvre, un fidèle de Bennerville, est là aussi.” During Boudin’s lifetime, he completed only five paintings of sailing vessels embellished with pennants in Deauville’s harbor. Three date to 1896 or 1897; one is undated; and one—the Nelson-Atkins panel—dates to 1895.22See Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), nos. 3019, 3547, 3552, 3554, and 3621, pp. 3:165, 353, 356, and 382. The Nelson-Atkins panel, no. 3554, is erroneously dated to 1896 in the catalogue raisonné, even though it bears the aforementioned inscription “Deauville Aout 1895.” We can thus be fairly certain that Boats Decorated with Flags was on Boudin’s easel when Soudan de Pierrefitte bumped into him and Lefebvre on August 19, 1895. Like other festivalgoers, Boudin was taking in the sights, sounds, and smells of summer merriment: the pageantry of the yachts, the boom of salvos from the nearby Le Havre squadron, the aroma of fresh seafood served at the casino, and much more. The regatta and its associated diversions had a transformative effect on the port that Boudin knew so well, and he was determined to capture this annual spectacle for posterity.

Notes

-

Quoted in Gustave Cahen, Eugène Boudin: Sa vie et son œuvre (Paris: H. Flory, 1900), 148. “Son enfance fut bercée sur la vague, au souffle du vent . . . et le ciel et la mer furent ses premières amours, auxquelles il demeura toujours fidèle.” All translations are by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

See Frederick Wedmore, Whistler and Others (London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons, 1906), 51; and Edward Alden Jewell, “Boudin Paintings Are Put On View,” New York Times (November 1, 1933).

-

Exposition of Paintings by the Late Louis Eugène Boudin, exh. cat. (New York: Durand-Ruel Galleries, 1898), unpaginated. Of course, Durand-Ruel had a vested interest in building Boudin’s renown.

-

Georges Jean-Aubry, Eugène Boudin d’après des documents inédits: L’Homme et l’œuvre (Paris: Editions Bernheim-Jeune, 1922), 17–19.

-

Boudin later claimed to have abandoned portraiture because the vogue for daguerreotypes reduced the demand for painted portraits. See Paul Leroi, “Salon de 1887 (suite),” L’Art: Revue bimensuelle illustrée, no. 556 (July 15, 1887): 32.

-

Laurent Manœuvre, “Eugène Boudin, Gustave Courbet et le développement de l’impressionnisme,” in Frédérique Thomas-Maurin, Julie Delmas, and Élise Boudon, eds., Courbet et l’impressionnisme, exh. cat. (Milan: Silvana, 2016), 44–45. According to a letter dated August 30, 1869, from Boudin to his friend Ferdinand Martin, Gauchez intended to market Boudin’s maritime scenes to collectors of Belgian seascapes, a strategy he had already employed for paintings by Johan Barthold Jongkind.

-

See Anna Bowman Dodd, Up the Seine to the Battlefields (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1920), 34–36; and Suzanne Cassidy, “The Thoroughbred Called Deauville,” New York Times, July 23, 1989. Some scholars argue that the duke’s role in transforming Deauville has been overstated; see Frédérique Citéra, “Deauville,” in Un siècle de bains de mer dans l’estuaire de la Seine, 1830–1930, exh. cat. (Honfleur: Musée Eugene Boudin, 2003), 36–39.

-

Carla Gottlieb, “Boudin’s Drawings,” Master Drawings 6, no. 4 (Winter 1968): 401. Boudin lived in relative poverty for much of his life. It was not until the early 1880s, when Durand-Ruel took notice of his work, that Boudin became financially secure.

-

Leroi, “Salon de 1887 (suite),” 33. “L’allure, les gréements et l’état de nos ports à notre époque.” Leroi quotes from a letter by Boudin to a mutual friend.

-

See “Normandy Impressionist Festival,” Times (London), April 24, 2010; and Seth Sherwood, “On the Cote Fleurie,” New York Times, August 8, 2010.

-

A Durand-Ruel label on the stretcher reads “Boudin No. 448 / Port de Deauville / 1884.” Durand-Ruel purchased Port of Deauville directly from Boudin in 1888. See Figure 9 in the technical entry.

-

For more on this subject, see Laurent Manœuvre, “Peinture de marines française, 1820–1905,” in Anne-Marie Bergeret-Gourbin and Dominique Lobstein, Honfleur entre tradition et modernité, 1820–1900, exh. cat. (Honfleur: Musée Eugène Boudin, 2010), 35–52.

-

For example, American journalist John Canaday acknowledged “assurance and finesse” in certain pictures by Boudin but claimed that he “could also be a rather monotonous painter.” John Canaday, “Boudin, Fantin-Latour and Newcomer,” New York Times (November 5, 1966).

-

Quoted in Jean-Aubry, Eugène Boudin, 183. Boudin’s works “éveillent les souvenirs précis, accentués, de promenades que nous aurions faites dans ces contrées, sur ces côtes diverses.”

-

Interestingly, Boudin painted the trail of smoke in the Nelson-Atkins picture before adding the sky. See technical notes by Mary Schafer, Nelson-Atkins paintings conservator, August 24, 2011, NAMA conservation files, 33-14/1.

-

Jean-Louis Lenhof, “Régates et navigation de plaisance en baie de Seine au XIXe siècle,” in Dominique Barjot, Eric Anceau, and Nicolas Stoskopf, eds., Morny et l’invention de Deauville (Paris: Armand Colin, 2010), 381–406. As Lenhof explains, yachting took two forms in nineteenth-century France: yachting de croisière and yachting de course, or cruising and racing. When used as cruise ships, yachts were essentially “traveling private mansions” that allowed their owners to sightsee while still enjoying the comforts of home. They offered a novel place to entertain guests and conduct business. When used as racing vessels, yachts were equally luxurious but differently equipped: they did not rely on steam propulsion, and their sails could adapt more easily to variable winds.

-

For example, in 1892 the Cercle de la Voile de Paris joined forces with a company in Trouville to host a three-day regatta in late July. See Henri Philippe, “Yachting-Gazette: Revue des régates à la voile en 1892,” Le Sport, no. 18 (March 3, 1893): 284–85.

-

Lenhof, “Régates et navigation de plaisance,” 385–86.

-

See RF 16785, RF 16794, RF 3350, and RF 16793 at the Musée d’Orsay. Another pastel drawing of a boat with flags was sold at Tableaux modernes et contemporains, Rémy Le Fur et Associés, Paris, December 3, 2012, lot 21 (Bateau pavoisé).

-

Jehan Soudan [de Pierrefitte], “À Trouville,” Le Journal, no. 1057 (August 20, 1895): 2. “Les gais pavillons et drapeaux flottants devant les rangs de parasols rouges.”

-

Soudan [de Pierrefitte], “À Trouville,” 2. “Surpris le maître E. Boudin, peignant du quai cette kermesse aquatique; le peintre Jules Lefebvre, un fidèle de Bennerville, est là aussi.”

-

See Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), nos. 3019, 3547, 3552, 3554, and 3621, pp. 3:165, 353, 356, and 382. The Nelson-Atkins panel, no. 3554, is erroneously dated to 1896 in the catalogue raisonné, even though it bears the aforementioned inscription “Deauville Aout 1895.”

Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Susan Pavlik Enterline, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.2088.

MLA:

Enterline, Susan Pavlik. “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.606.2088.

The Port of Deauville was likely painted en plein airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio., as Eugène Boudin sat beneath an umbrella at his easel overlooking Bassin Morny in Deauville (Fig. 7).1Deauville currently has two ports, the modern Port-Deauville (opened in the 1970s) and historic Bassin Morny. At the time Boudin painted The Port of Deauville, only the wet dock of Bassin Morny existed. In 1891, the avant-port, or outer harbor, was enclosed, and the Bassin des Yachts opened. See Marie-Noël Tournoux and Hébert Didier, “Port dit Port de Trouville-Deauville (ref. IA14003205),” POP: la plateforme ouverte du patrimoine, Ministère de la Culture, updated September 21, 2020, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/merimee/IA14003205; and “The Ports,” inDeauville Tourisme, accessed June 1, 2025, https://www.indeauville.fr/en/sejour/the-ports/. Comparison with contemporary photographs and maps indicate that Boudin was likely sitting along the southeastern end of the wet dock, looking out toward the outer harbor and the sea beyond. The composition was executed on a small, 25.7 x 35 x 2.3 cm wood panel with chamfered rear edges.2It seems unlikely that the panel was planed, as the chamfered edges continue behind the upper and lower horizontal battens. Around the perimeter, especially in the lower left and right corners, there are linear imprints in the paint, possibly from transporting the panel in an artist’s box or placing it in a frame while still wet (Fig. 8).3Lara Broecke makes the same two suggestions to explain similar markings on two Boudin panels, Au Havre (1887; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) and The Fishcart at Berck (1880; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). Broecke, “Notes on the Technique of Eugène Boudin,” Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, no. 4 (2013): 53. Along the upper edge and lower left corner there are sets of short grooves perpendicular to the edge, also made while the paint was still wet, which may relate to an easel.4Mary Schafer, technical notes, August 24, 2011, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 33-14/1.

Fig. 7. Photograph of Boudin at his easel with his portable paint box under an umbrella, clutching a handful of brushes. Anonymous, Eugène Boudin Painting on the Deauville Pier, June 1896, photograph, public domain.

Fig. 7. Photograph of Boudin at his easel with his portable paint box under an umbrella, clutching a handful of brushes. Anonymous, Eugène Boudin Painting on the Deauville Pier, June 1896, photograph, public domain.

Fig. 8. Digital radiograph showing impressions (visible as dark marks) in the wet paint along the left and right vertical edges (red arrows), The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884). Note also the series of short, grooved impressions (visible as dark marks) along the upper and lower edges of the panel (yellow arrows). The noticeable grid pattern in the x-ray is due to the different thicknesses created by the cradle; the added thickness in locations where there are battens is more difficult for x-rays to penetrate, in comparison to the panel alone.

Fig. 8. Digital radiograph showing impressions (visible as dark marks) in the wet paint along the left and right vertical edges (red arrows), The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884). Note also the series of short, grooved impressions (visible as dark marks) along the upper and lower edges of the panel (yellow arrows). The noticeable grid pattern in the x-ray is due to the different thicknesses created by the cradle; the added thickness in locations where there are battens is more difficult for x-rays to penetrate, in comparison to the panel alone.

Fig. 9. Image of the back of the panel, showing the cradle and the pink Durand-Ruel label, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 9. Image of the back of the panel, showing the cradle and the pink Durand-Ruel label, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

The panel has been cradledcradle: A grid-like wooden structure attached to the reverse of a panel by a restorer to prevent warping. using four horizontal fixed battens glued parallel to the grain, with four moving cross-members (Fig. 9). The panel is not of a standard sizestandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format.,5There is a note on the cradle: “10 x 13 ¾ odd size” handwritten in dark blue. though its measurements are similar to other panels painted by Boudin around the same time.6For examples of panels with similar dimensions, see accompanying “Related Works” section for this entry, as well as that of Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1894; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art): Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.4033, and “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” documentation, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.608.4033. There are no markings on the reverse, and it is unclear whether the panel came from an artist’s supplyartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant. shop or elsewhere.7In letters to his friend Ferdinand Martin, Boudin described purchasing wood panels from joiners, carpenters, and trunk merchants. See Isolde Pludermacher, Eugène Boudin, Lettres à Ferdinand Martin, 1861–1870, (Honfleur: Société des Amis du Musée Eugène Boudin, 2011), 1:104, 119, cited in Virginia Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)” (PGDip final year project, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2018), 9.

A commercially prepared, opaque, off-white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. was thinly and evenly applied, extending to the edge of the panel. Boudin then applied a thin, streaky washwash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent. of warm gray paint overall using a broad brush. There is evidence only of wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. paint application over this imprimaturaimprimatura: A thin layer of paint applied over the ground layer to establish an overall tonality., indicating that Boudin added the imprimatura far enough in advance that it had fully dried before his harborside painting session. Late in life, Boudin described his working process to the director of the Honfleur Museum, Léon Leclerc, noting what seems to be this imprimatura layer. Leclerc recounted that Boudin, “had the habit of covering the surface he wanted to paint in advance with a light smear of neutral tint, which allowed him to more quickly note the values, to obtain the clear notes straightaway, and to more easily and smoothly create an atmosphere.”8Leclerc recounted his 1897 conversation with Boudin at a centennial celebration of Boudin’s birth. See “Le Centenaire du Peintre Eugene Boudin,” L’Echo Honfleurais, October 4, 1924, 2: “Il m’apprit qu’il avait l’habitude de couvrir préalablement la surface qu’il voulait peindre, d’un léger frottis déteinte neutre, ce qui lui permettait de noter plus rapidement les valeurs, d’obtenir de suite les notes claires et de former plus facilement et plus souplement une ambiance.” All translations are by Susan Pavlik Enterline, unless otherwise noted. Passages relevant to Boudin’s painting methods are paraphrased in English in Ruth L. Benjamin, “Eugène Boudin, King of Skies,” American Magazine of Art 23, no. 3 (September 1931): 200. Passages of exposed imprimatura play an integral role in the tonal unification of the composition.

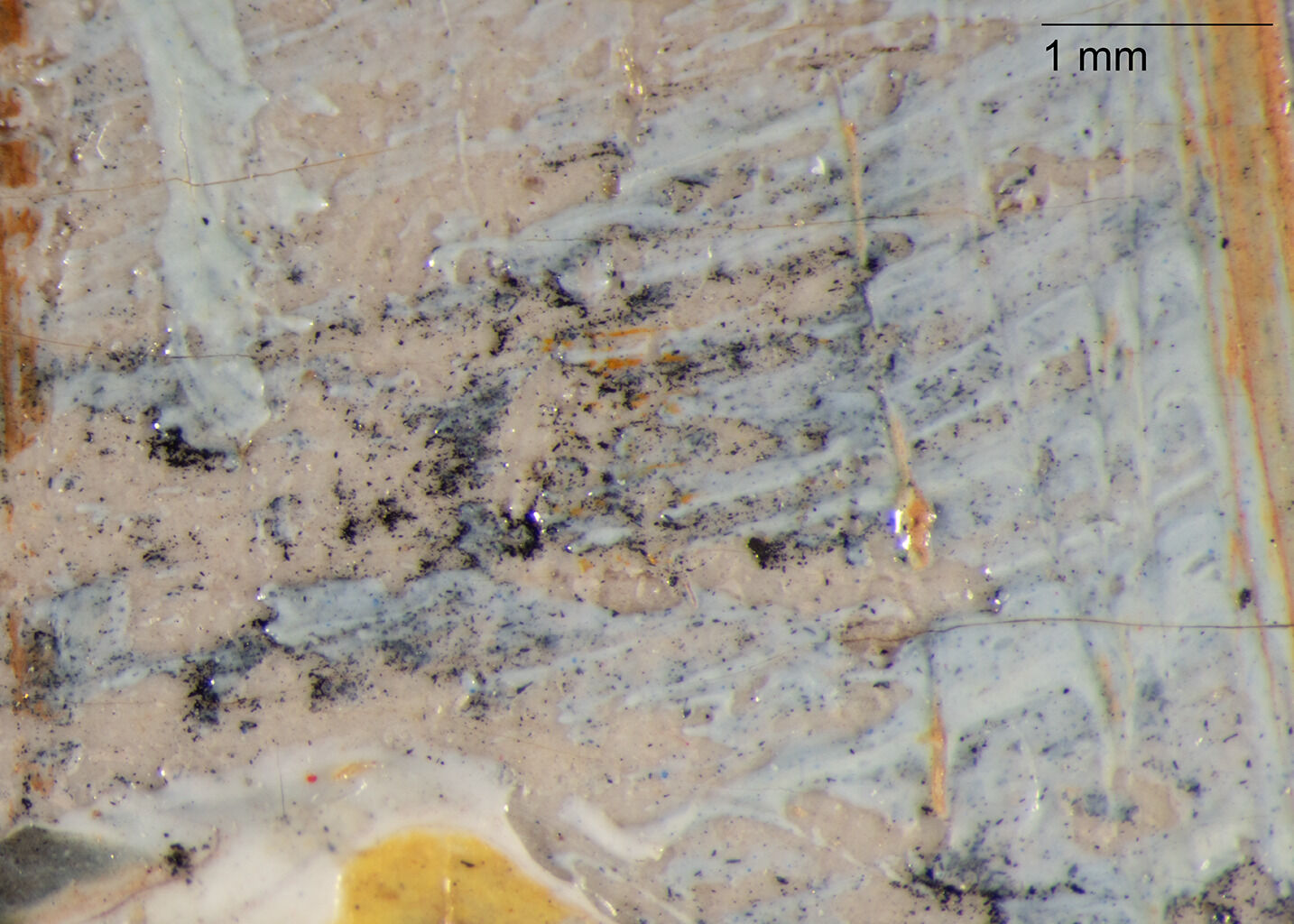

Key elements in the composition were sketched in with minimal underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint.. A few charcoal lines are visible beneath the sails and rigging (Fig. 10) and along the horizon line, establishing masts and other broad shapes. Under a stereomicroscope, dispersed charcoal particles appear elsewhere in the composition, likely the result of underdrawing media being lifted and blended by vigorous brushwork.9Nouwen mentions the same possibility in relation to Boudin’s Bassin de la Barre (1894; private collection). Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898),” 21.

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of charcoal underdrawing (yellow arrows) in the rigging to the left of the striped black smokestack, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884). Behind the smokestack, the roof of the customs house is represented by a single blue brushstroke.

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of charcoal underdrawing (yellow arrows) in the rigging to the left of the striped black smokestack, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884). Behind the smokestack, the roof of the customs house is represented by a single blue brushstroke.

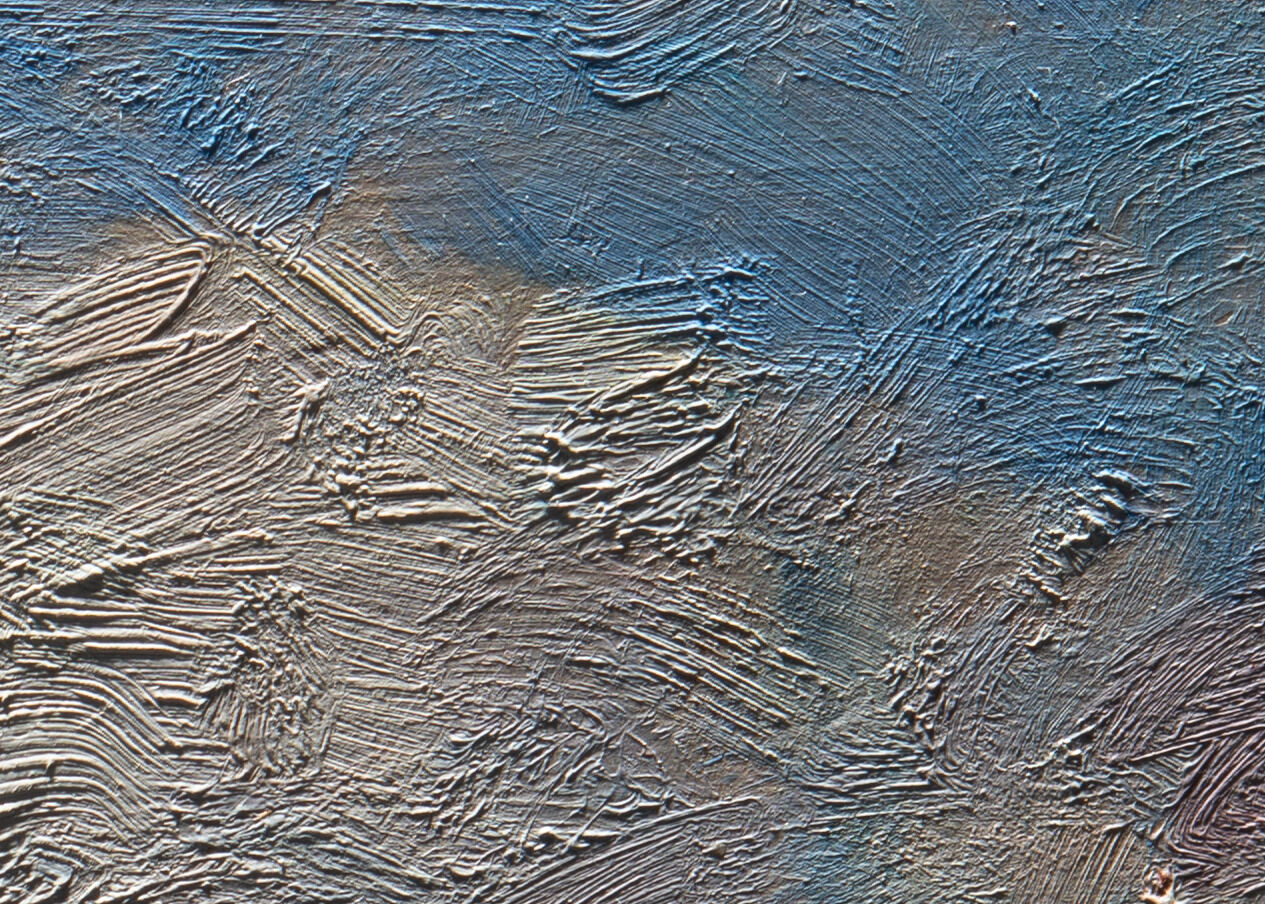

Fig. 11. Detail in raking light showing the juxtaposed textures of brushstrokes in the sky, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884). The complex layering of paint in the gray smoke cloud is also striking in raking light.

Fig. 11. Detail in raking light showing the juxtaposed textures of brushstrokes in the sky, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884). The complex layering of paint in the gray smoke cloud is also striking in raking light.

Boudin created movement within the scene using quick, painterly brushwork applied both wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. and wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface.. The sky is composed of crisscrossing strokes with varied thickness and texture. Smooth, buttery paint sits adjacent to heavy stippling (Fig. 11). While primarily blue, gray, and white, the sky also contains swipes of bright pink,10Although no analysis has been undertaken, the pink strokes exhibit a strong ultraviolet (UVA)-induced visible fluorescence, suggesting Boudin may have used a red lake. warm yellow, and deep blue.

Areas of exposed imprimatura along the horizon suggest the sky was added after the main elements of the port were painted. The black smokestack demonstrates this sequence, though the gray smoke cloud emanating from it shows iterative layering of blue sky over gray-black smoke, producing a complex combination of scumblingscumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. and wet-into-wet blending. More gray was added over the blue sky along the lower part of the cloud, followed by strokes of creamy yellow.

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph showing the sky carefully painted around the rigging of the rightmost ship, leaving visible an area of gray imprimatura, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph showing the sky carefully painted around the rigging of the rightmost ship, leaving visible an area of gray imprimatura, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of red, green, and orange highlights on the deck of the rightmost ship, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of red, green, and orange highlights on the deck of the rightmost ship, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Boudin constructed the raised sails of the square-rigged ships on the right using bold, thick strokes of warm and cool grays with touches of warm yellow, allowing areas of exposed imprimatura to act as midtones and fill out the shape of the sails. Once again, the sky was painted around the sails and yardarms (Fig. 12). The dark hulls of the ships were rendered in smooth, glossy strokes with swipes of grays and browns along their sides to represent reflections from the water. Bold highlights made up of bright colors are scattered across the decks and hulls of the ships (Fig. 13). Some of the final elements painted were the ships’ rigging, formed using wet-over-wet brushstrokes in tones ranging from deep black-brown and bluish-black to maroon and golden yellow (Fig. 14). Masts and larger cross-members were painted first, followed by the thinner and often much drier brushstrokes of the ropes and lines.

Fig. 14. Detail of the leftmost ship showing wet-over-wet brushstrokes forming the crisscrossing rigging, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 14. Detail of the leftmost ship showing wet-over-wet brushstrokes forming the crisscrossing rigging, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of the rightmost figure in the dinghy, showing a shift in the placement of the figure’s head, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of the rightmost figure in the dinghy, showing a shift in the placement of the figure’s head, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

In contrast to the robust execution of the ships, the commercial buildings and cranes on the right-hand dock are economically rendered in muted tones, some with a single brushstroke; figure 10 provides an example wherein one stroke of blue paint represents the roof of the customs house. Similarly, the bridge enclosing the harbor is painted with dashes of reddish-brown and gray, nearly disappearing into the red-roofed buildings on the horizon beyond. Given no more importance than the buildings, the figures in the dinghydinghy: A small boat carried on board, or towed behind, a larger vessel. are also comprised of just a few brushstrokes. A shift in the right figure’s head is the only noticeable change. The slightly higher original placement was painted out with light blue, leaving a slight pentimentopentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind." (Fig. 15).

Compared to the sky, the water is painted with narrower, gently sweeping horizontal brushstrokes in aquas, blues, and grays. Deep green, warm yellow, and reddish brown were worked wet-into-wet over the blue to represent the reflections of the ships on the surface of the water (Fig. 16). “E. Boudin” is signed in black and gray paint in the lower right corner over an area of textured paint (Fig. 17). Lines forming round letters like the “o” and “d” are disjointed as a result of Boudin’s brush passing across high points of the underlying, raised paint. There also appears to be an offset transfer of black paint that occurred before the signature was fully dry, most visible above the “B.”

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of wet-into-wet blending of color into the pale aqua water, representing reflections of the ships, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of wet-into-wet blending of color into the pale aqua water, representing reflections of the ships, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of Boudin’s signature in the lower right, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of Boudin’s signature in the lower right, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of a wood fragment embedded in the paint layer, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of a wood fragment embedded in the paint layer, The Port of Deauville (ca. 1884)

The panel is overall in good condition. There are several small cracksmechanical cracks: Cracks, either localized or overall, that form in response to movement or stress. through the paint layer which follow the wood grain, though there are no visible cracks extending into the panel. The cradle is no longer functioning as intended, as the once-sliding crosspieces are now fully immobile.11For information about cradles and related condition issues, see Paul Ackroyd, “The Structural Conservation of Paintings on Wooden Panel Supports,” in Conservation of Easel Paintings, ed. Joyce Hill Stoner and Rebecca Rushfield (London: Routledge, 2012), 453–78. There are abrasionsabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. and small losses in the paint layer that have been retouchedretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch.. Some of the retouching extends to cover abrasions over the signature. These impressions are consistent with a painting completed en plein air, as are the flecks of wood and other accretions in the paint layer (Fig. 18). A synthetic varnish, with moderate sheen, was applied during a 1989 conservation treatment.

Notes

-

Deauville currently has two ports, the modern Port-Deauville (opened in the 1970s) and historic Bassin Morny. At the time Boudin painted The Port of Deauville, only the wet dock of Bassin Morny existed. In 1891, the avant-port, or outer harbor, was enclosed, and the Bassin des Yachts opened. See Marie-Noël Tournoux and Hébert Didier, “Port dit Port de Trouville-Deauville (ref. IA14003205),” POP: la plateforme ouverte du patrimoine, Ministère de la Culture, updated September 21, 2020, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/merimee/IA14003205; and “The Ports,” inDeauville Tourisme, accessed June 1, 2025, https://www.indeauville.fr/en/sejour/the-ports/. Comparison with contemporary photographs and maps indicate that Boudin was likely sitting along the southeastern end of the wet dock, looking out toward the outer harbor and the sea beyond.

-

It seems unlikely that the panel was planed, as the chamfered edges continue behind the upper and lower horizontal battens.

-

Lara Broecke makes the same two suggestions to explain similar markings on two Boudin panels, Au Havre (1887; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) and The Fishcart at Berck (1880; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge). Broecke, “Notes on the Technique of Eugène Boudin,” Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, no. 4 (2013): 53.

-

Mary Schafer, technical notes, August 24, 2011, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 33-14/1.

-

There is a note on the cradle: “10 x 13 ¾ odd size” handwritten in dark blue.

-

For examples of panels with similar dimensions, see accompanying “Related Works” section for this entry, as well as that of Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1894; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art): Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.4033, and “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” documentation, https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.608.4033.

-

In letters to his friend Ferdinand Martin, Boudin described purchasing wood panels from joiners, carpenters, and trunk merchants. See Isolde Pludermacher, Eugène Boudin, Lettres à Ferdinand Martin, 1861–1870, (Honfleur: Société des Amis du Musée Eugène Boudin, 2011), 1:104, 119, cited in Virginia Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)” (PGDip final year project, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2018), 9.

-

Leclerc recounted his 1897 conversation with Boudin at a centennial celebration of Boudin’s birth. See “Le Centenaire du Peintre Eugene Boudin,” L’Echo Honfleurais, October 4, 1924, 2: “Il m’apprit qu’il avait l’habitude de couvrir préalablement la surface qu’il voulait peindre, d’un léger frottis déteinte neutre, ce qui lui permettait de noter plus rapidement les valeurs, d’obtenir de suite les notes claires et de former plus facilement et plus souplement une ambiance.” All translations are by Susan Pavlik Enterline, unless otherwise noted. Passages relevant to Boudin’s painting methods are paraphrased in English in Ruth L. Benjamin, “Eugène Boudin, King of Skies,” American Magazine of Art 23, no. 3 (September 1931): 200.

-

Nouwen mentions the same possibility in relation to Boudin’s Bassin de la Barre (1894; private collection). Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898),” 21.

-

Although no analysis has been undertaken, the pink strokes exhibit a strong ultraviolet (UVA)-induced visible fluorescence, suggesting Boudin may have used a red lake.

-

For information about cradles and related condition issues, see Paul Ackroyd, “The Structural Conservation of Paintings on Wooden Panel Supports,” in Conservation of Easel Paintings, ed. Joyce Hill Stoner and Rebecca Rushfield (London: Routledge, 2012), 453–78.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

Purchased from the artist by Durand-Ruel et Cie, Paris, stock no. 448, as Le Port de d’Eauville, March 30, 1888–February 10, 1933 [1];

Purchased from Durand-Ruel, Inc., New York, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1933 [2].

Notes

[1] The painting was transferred from Durand-Ruel’s Paris branch to their New York branch in October 1888. See email from Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel and Flavie Durand-Ruel, Durand-Ruel et Cie, to Nicole Myers, NAMA, January 11, 2016, NAMA curatorial files. Durand-Ruel photo no. A. 4; see photo stock card, Eugène Boudin, Landscapes and marines: Ch–De, Durand-Ruel NY Archives, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC. See also pink label on verso of panel that says: “Boudin No. 448 / Port [de d’] Eauville/ 1884.”

[2] The painting was shipped by Durand-Ruel to The Nelson-Atkins on February 6, 1933. See letter from Edwin C. Holston, Durand-Ruel et Cie, to William Rockhill Nelson Museum of Art, February 6, 1933, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid m. “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

Eugène Boudin, Port of Deauville, 1884, oil on panel, 18 1/2 x 15 in. (46.8 x 38.1 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale (London: Sotheby’s, June 20, 2019), 287.

Eugène Boudin, Cargo Ship in the Port of Deauville, 1884, oil on panel, 10 1/4 x 8 1/4 in. (26 x 21 cm), location unknown, cited in Dessins, Sculptures, et Tableaux Modernes (Paris: Audap et Mirabaud, June 4, 2014), 27.

Eugène Boudin, Port of Deauville, 1884, oil on panel, 11 x 8 5/8 in. (28 x 22 cm), location unknown, cited in Tableaux modernes (Versailles: Hôtel Rameau, December 18, 1988), 57.

Eugène Boudin, Port of Deauville, 1884, oil on panel, 12 5/8 x 16 1/8 in. (32 x 41 cm), cited in Impressionist and Modern Paintings (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, December 5, 1978), 18.

Eugène Boudin, Port of Deauville, 1884, oil on panel, 9 x 12 5/8 in. (23 x 32 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts de Liège, Belgium.

Eugène Boudin, Port of Deauville, 1884, oil on panel, 9 1/4 x 13 in. (23.5 x 32.9 cm.), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Art: Works on Paper and Day Sale (London: Christie’s, June 21, 2018), 340.

Eugène Boudin, Port of Deauville, 1884, oil on panel, 10 5/8 x 13 3/4 in. (27 x 35 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 1813, p. 2:198.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

Possibly French Impressionist Landscape Painting, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, November 29–December 30, 1936, hors cat.

Landscapes of the European War Theatre, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 1–February 15, 1944, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.606.4033.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 21, as Port of Deuville [sic].

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 30.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 53, 136, (repro.), as Port of Deuville [sic].

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Cezanne and the Patches of Color by Which He Transformed Modern Art,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 120 (January 15, 1934): [16]D, as Port of Deuville [sic].

Possibly “A Thrill to Art Expert: M. Jamot is Generous in his Praise of Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Times 97, no. 247 (October 15, 1934): 7.

Ellen Josephine Green, “The Fine Arts,” Musical Bulletin 23, no. 2 (November 1934): 7, as The Port of Deauville.

Possibly M[inna] K. P[owell], “In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art,” Kansas City Star 57, no. 71 (November 27, 1936): 34.

Possibly “Exhibition of French Impressionist Landscape Paintings,” News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 3, no. 2 (December 1, 1936): 2.

Ruth L. Benjamin, Eugène Boudin (New York: Raymond and Raymond, 1937), 188, as Port of Deauville.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 167, as Port of Deauville.

“Temporary Exhibitions: Landscapes of the European War Theatre,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 10, no. 5 (January 1944): 1.

H. C. H., “Scenes of Old Europe: Nelson Gallery Presents a Continent As It Was,” Kansas City Times 107, no. 6 (January 7, 1944): 4.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 260, as Port of Deauville.

Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Robert Schmit, 1973), no. 1809, pp. 2:197, 3:CIX, CXXII, CXLIII, (repro.), as Deauville. Le Bassin.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 257, as Port of Deauville.

Possibly Gilbert de Knyff, Eugène Boudin raconté par lui-même: sa vie, son atelier, son œuvre (Paris: Éditions Mayer, 1976), 237.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 38, 40, (repro.), as The Port of Deauville.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries Feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0, (repro.).

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/

Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Susan Pavlik Enterline, “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.608.2088.

MLA:

Enterline, Susan Pavlik. “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.608.2088.

Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville was painted on a wooden panel, estimated to be mahogany.1No testing was conducted; the wood was identified as mahogany by Scott A. Heffley (examination report, April 4, 1993, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2015.13.3), and the identification was corroborated by Joe Rogers, objects conservator at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The panel measures 26.8 x 34.9 x 7 centimeters,2The panel’s dimensions correspond in size to a French standard-format no. 5 paysage canvas, though not to any standard-format panel listed in Lefranc et Cie’s 1899 catalogue; see Anthea Callen, The Work of Art (London: Reaktion Books, 2015), 88–89. Few existing catalogues from the period include a list of sizes for standard-format panels, and it is entirely possible that artist suppliers stocked panels in these dimensions. and its reverse edges are beveled. The panel feels nearly weightless, a benefit to an artist like Eugène Boudin who carried his materials outdoors. “PIGNEL DUPONT 17 RUE LEPIC PARIS”3Pignel Dupont operated in Paris from 1885 to 1895 (Pascal Labreuche, “Pignel Dupont,” Guide Labreuche: The Guide to Suppliers of Artists’ Materials, France 18th–20th Centuries, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.guide-labreuche.com/en/collection/businesses/pignel-dupont). The words are punched into the panel, which has been rotated ninety degrees clockwise from upright. (Fig. 19) has been stampedsupplier mark: A mark (ink stamp, brand, impression, etc.), often present on the reverse of canvas, panel, or other support, signifying the company that sold or prepared the support. As these companies sometimes performed framing and restorations, these marks could also reflect these services. See also canvas stamp. into the back of the panel, and the entire reverse has been painted brown.4Panels with Pignel Dupont supplier stamps used by other artists (e.g. Alain Bonnaud, Barque sur la rivière, sold at Champagne Auctions, Montreal, May 28, 2019, https://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/bonnaud-alain-barque-sur-la-riviere-45-c-da14bddb13) are unpainted on the reverse, suggesting that the reverse of the Nelson-Atkins panel was painted brown either by the artist or after it left his hands.

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph showing part of the supplier mark on the reverse of the panel, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph showing part of the supplier mark on the reverse of the panel, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of wood exposed where the ground layer does not extend to the edge of the panel, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig. 20. Photomicrograph of wood exposed where the ground layer does not extend to the edge of the panel, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Despite purchasing the panel from an artist supplierartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant., Boudin seems to have applied the ground layerground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. himself. The off-white ground was thinly applied and does not extend to the edges of the panel, leaving areas of wood exposed along the sides (Fig. 20). In contrast to Port of Deauville (ca. 1884; The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art),5See accompanying technical entry by Susan Pavlik Enterline, “Eugène Boudin, Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.2088. there is no imprimaturaimprimatura: A thin layer of paint applied over the ground layer to establish an overall tonality. layer, though Boudin took advantage of the warm tones of the panel to achieve a similar end.6Lara Broecke mentions a similar phenomenon with the thin paint layer in Au Havre (1887; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) in Broecke, “Notes on the Technique of Eugène Boudin,” Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, no. 4 (2013): 51. As in many of his works, large areas of ground are visible between passages of paint in the final composition. The ground retains a relatively smooth, matte surface compared to the thicker, glossier paint layers (Fig. 21).

Fig. 21. Detail in raking illumination showing the flat, matte ground compared to the thicker, glossier brushstrokes of the paint, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig. 21. Detail in raking illumination showing the flat, matte ground compared to the thicker, glossier brushstrokes of the paint, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

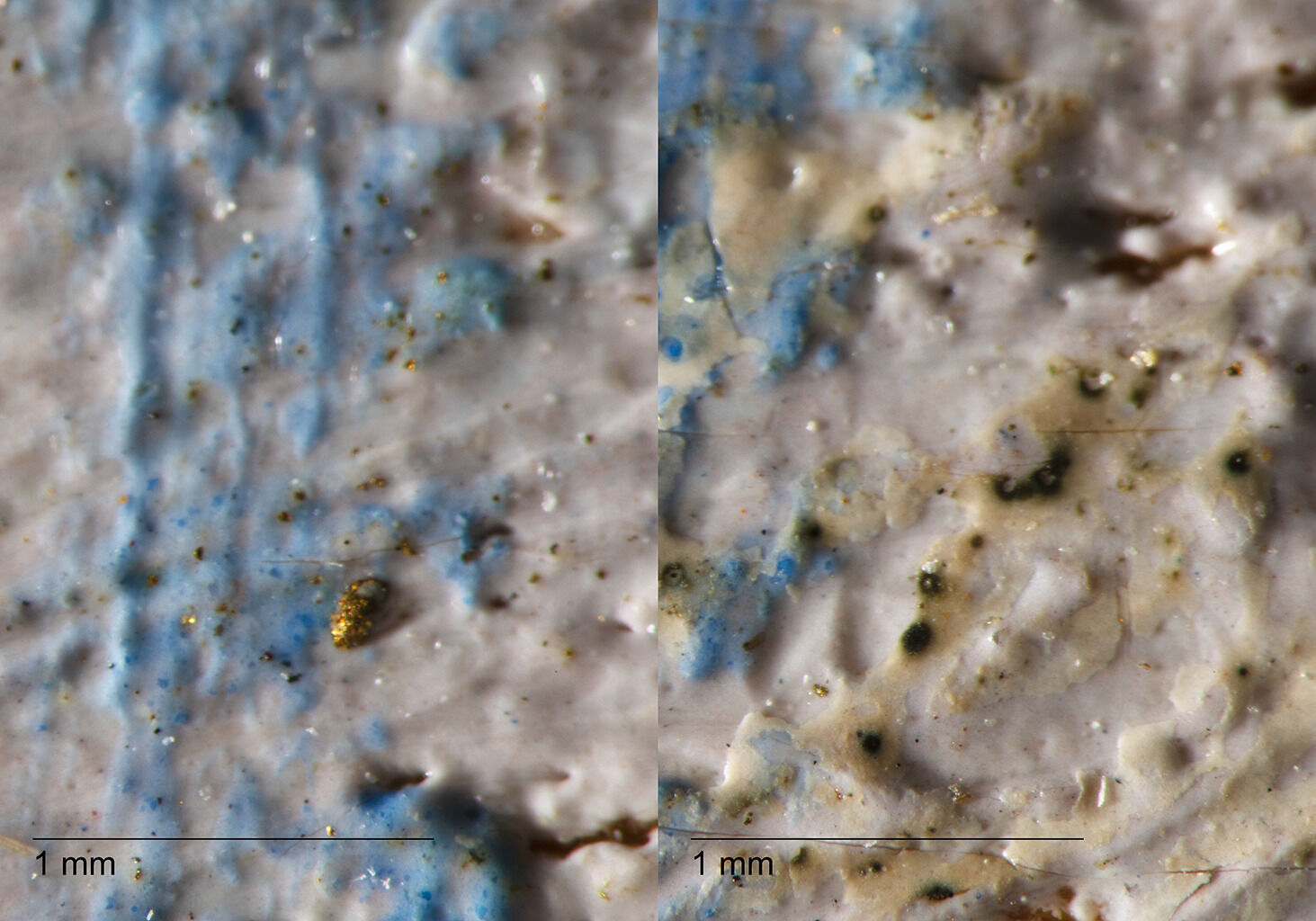

Fig. 22. Photomicrograph of the charcoal underdrawing along the deck of the leftmost ship, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig. 22. Photomicrograph of the charcoal underdrawing along the deck of the leftmost ship, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Under magnification, underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. estimated to be charcoal remains visible along the decks of the ships (Fig. 22) and beneath rigging. The reflected infrared (IR) imagereflected infrared digital photograph: An infrared image produced in the 700–1000 nanometer range, typically captured using an infrared-modified digital camera. See infrared photography. reveals a line of charcoal in the rightmost ship’s rigging, likely a rope that was never painted into the final composition (Fig. 23). Dispersed charcoal particles throughout the paint surface are likely the result of Boudin’s vigorous brushwork moving the dry media of the underdrawing.7Dispersed charcoal particles were also identified in The Port of Deauville, and by Virginia Nouwen in “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)” (PGDip final year project, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2018), 21.

Fig. 23. Details of the rigging of the rightmost ship, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895). On the left is a normal illumination photograph. On the right is a reflected infrared digital photograph that reveals a line of charcoal underdrawing (see arrow).

Fig. 23. Details of the rigging of the rightmost ship, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895). On the left is a normal illumination photograph. On the right is a reflected infrared digital photograph that reveals a line of charcoal underdrawing (see arrow).

Fig. 24. Photomicrograph of the hull of the white ship near the center of the painting, showing brown, reticulating lines of a painted underdrawing outlining the ship (see arrows), Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895). Note also the brushstrokes of various colors used to represent the white hull.

Fig. 24. Photomicrograph of the hull of the white ship near the center of the painting, showing brown, reticulating lines of a painted underdrawing outlining the ship (see arrows), Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895). Note also the brushstrokes of various colors used to represent the white hull.

In addition to his charcoal sketch, Boudin developed the outlines of the boats and other details along the horizon using quick strokes of thin, washywash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent. paint in blackish-brown and brownish-violet.8Nouwen writes of “a dilute oil paint layer . . . to outline the forms” in her discussion of underlayers in Boudin’s works. Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin,” 19. This painted underdrawing remains visible in the negative space below the bridge and in the white hull of the ship to the left of the bridge (Fig. 24). Léon Leclerc recalls these early stages after watching Boudin work: “He sketched quickly in large masses without any concern for detail; from a distance one already had the impression of a finished painting, whereas up close one only saw shapeless tones placed side by side.”9Leclerc, director of the Honfleur Museum, related his experiences talking with Boudin and watching him paint in 1897. See Leclerc, “Le Centenaire du Peintre Eugène Boudin,” L’Echo Honfleurais, October 4, 1924, 2: “Il ébauchait vivement par larges masses sans aucun souci du détail, de loin on avait déjà l’impression d’un tableau achevé alors que de près on n’apercevait que tons informes mis les uns a cote des autres.” All translations are by Susan Pavlik Enterline, unless otherwise noted. Passages relevant to Boudin’s painting methods are paraphrased in English in Ruth L. Benjamin, “Eugène Boudin, King of Skies,” American Magazine of Art 23, no. 3 (September 1931): 200.

LeClerc continues: “He observed carefully, seemed to meditate, then suddenly, the brush laden with color would land on the canvas, marking sometimes a simple point, sometimes a line, sometimes a tachetache: French for “blot” or “stain.” An application of a single color of paint, quite thickly applied, using a bold, flat and even-loaded stroke.".”10Leclerc, “Le Centenaire du Peintre Eugène Boudin,” 2: “Il observait attentivement, semblait méditer, puis tout à coup, le pinceau chargé de couleur se posait sur la toile, marquant tantôt un simple point, tantôt une ligne, tantôt une tache.” For an overview of the tache, see Øystein Sjåstad, A Theory of the Tache in Nineteenth-Century Painting (Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate, 2014). This juxtaposition of quiet contemplation and bustling activity is evident in the blend of wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. and wet-over-drywet-over-dry: An oil painting technique that involves layering paint over an already dried layer, resulting in no intermixing of paint or disruption to the lower paint strokes. brushwork throughout the composition (Fig. 25). Areas of wet-over-dry brushwork imply that the landscape was completed over a period of time. However, the combination of Boudin’s rapid brushwork and materials (thin ground applied to an absorbent panel),11The absorbency of an unprimed wood panel allowed for more rapid working. See Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George, and Katja Lewerentz, Painting Light: The Hidden Techniques of the Impressionists (Milan: Skira, 2008), 53. accompanied by warm, sunny weather,12Higher temperatures increase the rate of solvent evaporation and oxidation, leading to faster film formation. See Rutherford J. Gettens and George L. Stout, Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopaedia (1942; repr. New York: Dover, 1966), 38. may have allowed him to paint the landscape in one sitting.13It is likely Boudin worked on multiple panels in one sitting; Yacht Basin at Trouville-Deauville (1895–96; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) depicts the same boats with flags from the same vantage point. Working on multiple panels concurrently—setting one aside to work on another, then returning to the first—might allow time for film formation, the first step in the drying process., 14An opposing argument is made by Broecke, who argues that Boudin painted only the center band of detail en plein air, and the sky and sea (or land) in the studio. See Broecke, “Notes on the Technique of Eugène Boudin,” 50–51, 53. In one passage, for example, the paintbrush was dragged across the wet surface, creating a deep furrow in the underlying paint, while directly adjacent is a tache of similar color that lightly touches the white paint, wet-over-dry, without disrupting the outer skin of the curing paint (Fig. 26).

Fig. 26. Photomicrograph of adjacent wet-over-wet and wet-over-dry brushwork, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895). A vertical blue-gray stroke is visible at the bottom of the photograph, traveling upward and leaving a furrow in the wet paint of the sky. Above this stroke, there is a wet-over-dry tache containing similar paint colors and apparently placed using the same brush just after the wet-over-wet paint stroke.

Fig. 26. Photomicrograph of adjacent wet-over-wet and wet-over-dry brushwork, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895). A vertical blue-gray stroke is visible at the bottom of the photograph, traveling upward and leaving a furrow in the wet paint of the sky. Above this stroke, there is a wet-over-dry tache containing similar paint colors and apparently placed using the same brush just after the wet-over-wet paint stroke.

Fig. 27. Detail in raking illumination, showing wet-over-dry application of blue paint over a white cloud with intact textured brushstrokes, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig. 27. Detail in raking illumination, showing wet-over-dry application of blue paint over a white cloud with intact textured brushstrokes, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Boudin’s brushes moved back and forth between the sky, the sea, and the band of detail along the horizon, painting across the composition concurrently and returning to add a point, a line, or a tache. The sky was laid in using blue and white, and then masts and rigging were painted with a thin brush, using wet-over-wet strokes in brown, blue, and black. Boudin added thick, colorful brushstrokes to represent the flags strung along the rigging before returning to the sky. The expanse of brilliant blue in the upper right is layered over clouds already beginning to dry, leaving the impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. texture of the white brushstrokes intact (Fig. 27). There are strokes of muted red, yellow, and greenish blue, possibly indicating a shift of a flag’s location, or perhaps paint from the flag remained in Boudin’s brush as he continued painting the sky.

The harbor is mostly blue, white, and turquoise water, interspersed with swipes of red, green, and yellow representing reflections of boats. The luminous darkness of the lefthand ships’ hulls comes from a combination of deep brown, blue, and red, with thin lines of yellow highlights. The white ship at the center is a complex amalgam of red, pale blue, brown, and white, again highlighted with thin swipes of yellow, as seen in Figure 24. Traction crackstraction cracks: Also known as drying cracks, these are formed as the paint dries. They are usually the result of a “lean” paint with a small percentage of oil drying faster than an underlying “fat” paint layer with a higher percentage of oil. The quick drying of the top layer causes the paint layer to shrink and crack. appear throughout the painting, especially in the detail along the horizon. For example, cracks run through the hull of the ship to the left (Fig. 28), as well as throughout the figures to the right of the bridge.

The painting is generally in good condition. There are minor scrapes, indentations, and gouges around the back perimeter, indicating the panel was secured into a frame using nails. Along the upper edge of the panel, there are small losses, the two largest of which measure approximately one centimeter; there is also a small split measuring two centimeters, which appears stable. A small split in the lower proper left corner was stabilized during a 2018 treatment.15Mary Schafer, treatment report, January 12, 2018, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2015.13.3. There are a handful of tiny paint losses across the sky, and there are some abrasionsabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. around the perimeter. Abrasions, scattered losses, and old overpaintoverpaint: Restoration paint that covers original paint that may or may not be damaged. Historically, overpaint has often been applied too broadly, altering the intended aesthetic of the painting and sometimes introducing conceptions foreign to the original artist, thereby altering our understanding of the work and the era to which it belongs. were retouchedretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. during a 1993 treatment.16Scott A. Heffley, treatment report, April 20, 1993, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2015.13.3. At the same time, the painting received two layers of synthetic varnish, which remain clear and have a moderate sheen, though the retouching is slightly discolored.

Fig 29. Photomicrograph showing gilding embedded into linear impressions found along the right edge, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig 29. Photomicrograph showing gilding embedded into linear impressions found along the right edge, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig. 30. Photomicrographs comparing intact gold-colored flakes (left) and cavities and staining beneath retouching media (right), Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

Fig. 30. Photomicrographs comparing intact gold-colored flakes (left) and cavities and staining beneath retouching media (right), Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville (1895)

There is abundant plant matter, wood, and other material embedded in the wet paint, and some impasto has been flattened. There are also linear impressions in the wet paint along the sides of the painting;17See accompanying technical entry by Susan Pavlik Enterline, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.2088. microscopic examination reveals embedded gilding (Fig. 29), indicating the painting was framed before it was fully dry. On the far right above the red flag, there is a cluster of tiny dark spots, possibly related to framing. Under magnification, the spots are a mixture of gold-colored particles embedded in the paint and miniscule cavities surrounded by greenish staining (Fig. 30). In some areas, the particles remain intact, but where they are coated by retouching, it appears the metal has corroded, leaving behind a cavity and the associated staining.18Bronze paint was a common material on frames at the end of the nineteenth century, and its high copper content correlates with the greenish color of the corrosion present around the cavities. Instrumental analysis would be required to confirm the presence of bronze and its corrosion products on the surface of the painting.

Notes

-

No testing was conducted; the wood was identified as mahogany by Scott A. Heffley (examination report, April 4, 1993, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2015.13.3), and the identification was corroborated by Joe Rogers, objects conservator at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

The panel’s dimensions correspond in size to a French standard-format no. 5 paysage canvas, though not to any standard-format panel listed in Lefranc et Cie’s 1899 catalogue; see Anthea Callen, The Work of Art (London: Reaktion Books, 2015), 88–89. Few existing catalogues from the period include a list of sizes for standard-format panels, and it is entirely possible that artist suppliers stocked panels in these dimensions.

-

Pignel Dupont operated in Paris from 1885 to 1895 (Pascal Labreuche, “Pignel Dupont,” Guide Labreuche: The Guide to Suppliers of Artists’ Materials, France 18th–20th Centuries, accessed July 16, 2025, https://www.guide-labreuche.com

/en ). The words are punched into the panel, which has been rotated ninety degrees clockwise from upright./collection /businesses /pignel-dupont -

Panels with Pignel Dupont supplier stamps used by other artists (e.g. Alain Bonnaud, Barque sur la rivière, sold at Champagne Auctions, Montreal, May 28, 2019, https://www.invaluable.com

/auction-lot ) are unpainted on the reverse, suggesting that the reverse of the Nelson-Atkins panel was painted brown either by the artist or after it left his hands./bonnaud-alain-barque-sur-la-riviere-45-c-da14bddb13 -

See accompanying technical entry by Susan Pavlik Enterline, “Eugène Boudin, Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.2088.

-

Lara Broecke mentions a similar phenomenon with the thin paint layer in Au Havre (1887; Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge) in Broecke, “Notes on the Technique of Eugène Boudin,” Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, no. 4 (2013): 51.

-

Dispersed charcoal particles were also identified in The Port of Deauville, and by Virginia Nouwen in “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)” (PGDip final year project, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2018), 21.

-

Nouwen writes of “a dilute oil paint layer . . . to outline the forms” in her discussion of underlayers in Boudin’s works. Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin,” 19.

-

Leclerc, director of the Honfleur Museum, related his experiences talking with Boudin and watching him paint in 1897. See Leclerc, “Le Centenaire du Peintre Eugène Boudin,” L’Echo Honfleurais, October 4, 1924, 2: “Il ébauchait vivement par larges masses sans aucun souci du détail, de loin on avait déjà l’impression d’un tableau achevé alors que de près on n’apercevait que tons informes mis les uns a cote des autres.” All translations are by Susan Pavlik Enterline, unless otherwise noted. Passages relevant to Boudin’s painting methods are paraphrased in English in Ruth L. Benjamin, “Eugène Boudin, King of Skies,” American Magazine of Art 23, no. 3 (September 1931): 200.

-

Leclerc, “Le Centenaire du Peintre Eugène Boudin,” 2: “Il observait attentivement, semblait méditer, puis tout à coup, le pinceau chargé de couleur se posait sur la toile, marquant tantôt un simple point, tantôt une ligne, tantôt une tache.” For an overview of the tache, see Øystein Sjåstad, A Theory of the Tache in Nineteenth-Century Painting (Farnham, U.K.: Ashgate, 2014).

-

The absorbency of an unprimed wood panel allowed for more rapid working. See Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George, and Katja Lewerentz, Painting Light: The Hidden Techniques of the Impressionists (Milan: Skira, 2008), 53.

-

Higher temperatures increase the rate of solvent evaporation and oxidation, leading to faster film formation. See Rutherford J. Gettens and George L. Stout, Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopaedia (1942; repr. New York: Dover, 1966), 38.

-

It is likely Boudin worked on multiple panels in one sitting; Yacht Basin at Trouville-Deauville (1895–96; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC) depicts the same boats with flags from the same vantage point. Working on multiple panels concurrently—setting one aside to work on another, then returning to the first—might allow time for film formation, the first step in the drying process.

-

An opposing argument is made by Broecke, who argues that Boudin painted only the center band of detail en plein air, and the sky and sea (or land) in the studio. See Broecke, “Notes on the Technique of Eugène Boudin,” 50–51, 53.

-

Mary Schafer, treatment report, January 12, 2018, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2015.13.3.

-

Scott A. Heffley, treatment report, April 20, 1993, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 2015.13.3.

-

See accompanying technical entry by Susan Pavlik Enterline, “Eugène Boudin, The Port of Deauville, ca. 1884,” https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.606.2088.

-

Bronze paint was a common material on frames at the end of the nineteenth century, and its high copper content correlates with the greenish color of the corrosion present around the cavities. Instrumental analysis would be required to confirm the presence of bronze and its corrosion products on the surface of the painting.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.608.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.608.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.608.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.608.4033.

With Galerie Allard et Noël, Paris;

With Stephen Hahn, New York, by November 12, 1968 [1];

Eugene B. (1917–2003) and Lucy (née Harvey, 1921–2006) Sydnor, Jr., Richmond, VA, by May 7, 1972–April 1, 1993 [2];

Purchased from Eugene and Lucy Sydnor, Jr. through Martha Parrish, Inc., New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1993–June 15, 2015 [3];

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] November 12, 1968 is the opening date of XIX and XX Century French Paintings: Recent Acquisitions, an exhibition held at Stephen Hahn Gallery, New York, that included Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville. According to a Hahn family representative, Stephen Hahn’s business records do not survive. See email from Janey Campbell, Music Academy of the West, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, June 3, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] May 7, 1972 is the opening date of European and American Art from Princeton Alumni Collections, an exhibition to which the Sydnors lent Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville. After Eugene B. and Lucy Sydnor, Jr., divorced in 1986, it is unclear if they retained joint ownership of the painting or if one of them assumed full ownership.

[3] See email from Ann Restak, James Reinish and Associates, Inc., to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, May 26, 2015, NAMA curatorial files. A label from Martha Parrish, Inc., can be found on the panel’s verso.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.608.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid m. “Eugène Boudin, Boats Decorated with Flags in the Port of Deauville, 1895,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.608.4033.

Eugène Boudin, Le Havre, the Regatta Festival, 1869, oil on panel, 8 1/2 x 15 in. (21.5 x 38 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Nineteenth Century Art (New York: Christie’s, November 18, 1998), 10–11.

Eugène Boudin, The Regatta at Le Havre, ca. 1858–62, oil on panel, 5 1/2 x 10 7/8 in. (14 x 27.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 189, p. 1:60.