Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865, and Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” catalogue entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.602.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865, and Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.602.5407.

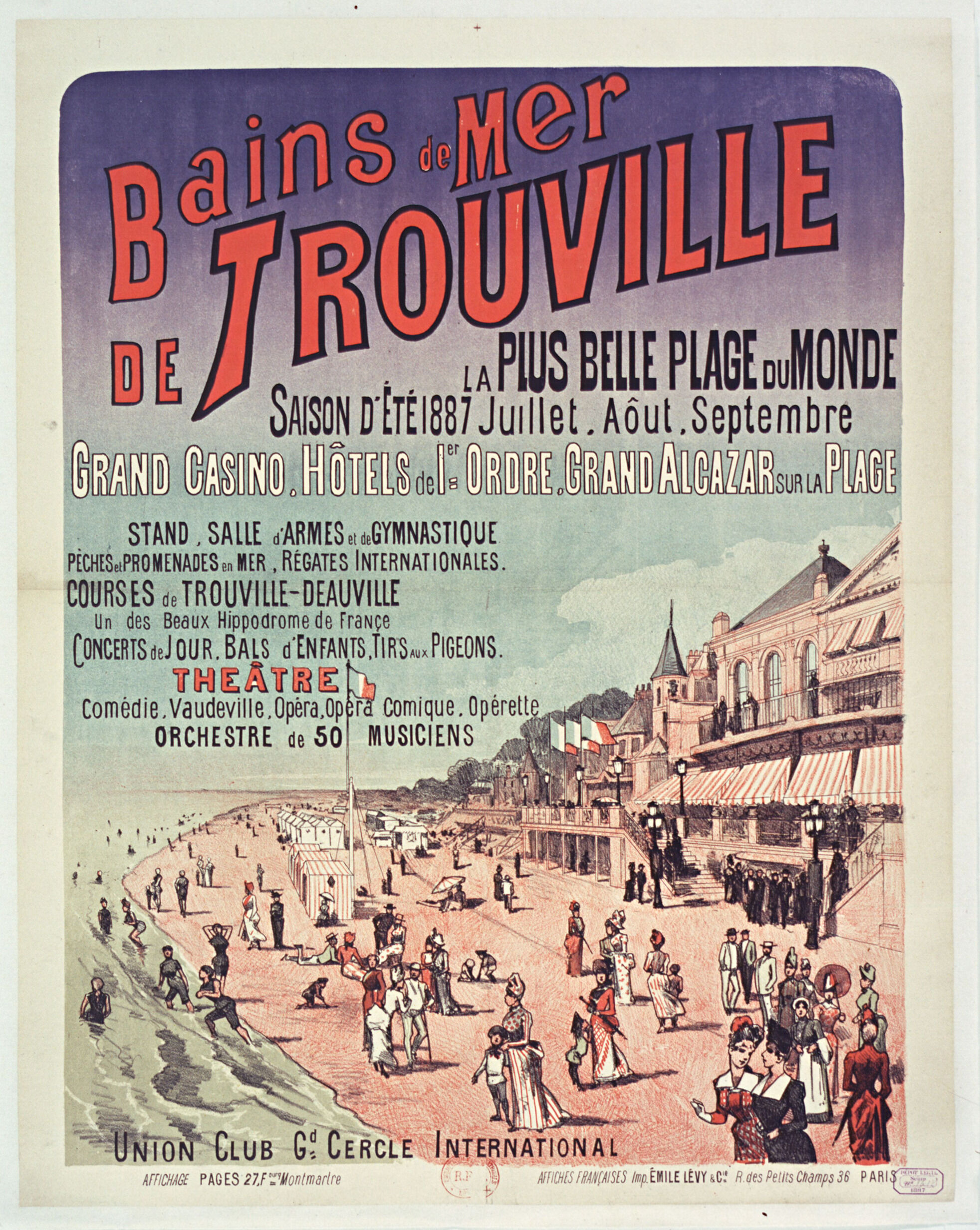

“I was desperate; I had to get out of this stone prison at all costs, and I resolved to visit Trouville. The crush of dazed travelers proved that I was not alone in feeling the urgent need for a little bit of fresh air.”1Léon Arbaud [Mme Lenormant], “Chronique du bord de la mer,” La Semaine des familles, no. 50 (September 12, 1863): 797–800. “J’étais au désespoir; à tout prix il me fallait sortir de cette prison de pierres, et je résolus de venir à Trouville. La cohue de voyageurs ahuris me prouva que je n’étais pas seul à ressentir l’impérieux besoin d’un peu d’air libre.” All translations by Brigid M. Boyle. So begins a travel piece by the Parisian journalist Léon Arbaud from the summer of 1863. Like many residents of the City of Light, Arbaud felt confined by the narrow streets and crowded spaces—the urban renewal scheme undertaken by Napoleon III’s appointee, Baron Haussmann, was still ongoing—and so he decided that the only solution was a weekend getaway to the coast of Normandy. Seaside holidays were already a well-established tradition in many parts of Europe; French aristocrats had borrowed this practice from their British peers early in the nineteenth century.2Vivien Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, exh. cat. (London: John Murray, 1992), 53. However, advances in rail technology and a midcentury surge in trains de plaisir (round-trip rail service from Paris to the shore) made littoral towns more accessible than ever before.3Sylvie Gache-Patin and Scott Schaefer, “Impressionism and the Sea,” in Andrea P. A. Belloli, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), 273–78. For a period rendering of Parisians jostling to board such a train, see Honoré Daumier, Les trains de plaisir, 1864, lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.577. Each summer, Parisians seeking a respite from urban life flocked to the beaches in greater numbers than the previous year.

Trouville was also a magnet for artists. Eugène Boudin (1824–98) is believed to have first visited this resort in June 1862.10Georges Jean-Aubry, Eugène Boudin d’après des documents inédits: L’Homme et l’œuvre (Paris: Editions Bernheim-Jeune, 1922), 51. Other artists who painted at Trouville include Jules Achille Noël (1815–81), Richard Parkes Bonington (1802–28), Louis Alexandre Dubourg (1821–91), Charles Louis Mozin (1806–62), and Charles François Pécrus (1826–1907). Born in Normandy, he typically spent the winter in Paris and the summer closer to home, often at Trouville or its sister town, Deauville. During those summer sojourns, Boudin produced hundreds of beach scenes, two of which belong to the Nelson-Atkins. The earlier of these two is a pastel known simply as The Beach. Boudin began experimenting with pastel in the late 1840s, making rapid studies of cloud formations that earned the praise of both the writer Charles Baudelaire and the painter Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875).11Gustave Cahen, Eugène Boudin, sa vie et son oeuvre (Paris: H. Flory, 1900), 113. These studies likely served as aide-mémoires for his oil paintings. He continued to use pastel masterfully throughout his five-decade career, even though he rarely exhibited his pastel drawings or considered them autonomous works.12John House, “Boudin’s Modernity,” in Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, 16. The Nelson-Atkins pastel bears no date, but it must have been created in the mid-1860s since it passed through the Galerie Cadart et Luquet in Paris, a short-lived partnership between Alfred Cadart (1828–75) and Jules Joseph Luquet (b. 1824) that existed from October 1863 to October 1867.13For more on this gallery, see Monique Nonne, “Alfred Cadart (1828–1875), marchand de tableaux modernes,” Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art français (2009): 363–73. At that time, Boudin was still struggling to make ends meet, and most of his patrons were from Le Havre, where his parents lived.14Michael Clarke, “Boudin: Le Havre,” Burlington Magazine 158, no. 1364 (November 2016): 921.

Fig. 3. Eugène Boudin, Two Riders on the Beach, ca. 1864–68, pastel on paper laid down on paper, 7 1/8 x 10 ¾ in. (18.1 x 27.3 cm), private collection. Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images

Fig. 3. Eugène Boudin, Two Riders on the Beach, ca. 1864–68, pastel on paper laid down on paper, 7 1/8 x 10 ¾ in. (18.1 x 27.3 cm), private collection. Photo © Christie’s Images/Bridgeman Images

Fig. 4. Eugène Boudin, A Rider and Elegant People on a Beach, 1866, watercolor and graphite on paper, 5 11/16 x 9 11/16 in. (14.5 x 24.6 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF18207-recto-folio1. Photo: Tony Querec © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 4. Eugène Boudin, A Rider and Elegant People on a Beach, 1866, watercolor and graphite on paper, 5 11/16 x 9 11/16 in. (14.5 x 24.6 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF18207-recto-folio1. Photo: Tony Querec © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Boudin continued to represent the beach on and off for the rest of his professional life. He even developed his own subcategory of seaside images—bands of chic bourgeois holidaymakers socializing on the coast of Trouville or Deauville. According to Scottish art historian Vivien Hamilton’s tally, Boudin completed more than three hundred such paintings between 1862 and 1895, an astounding number that does not take into account his many renditions of this theme in pastel and watercolor.20Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, 64. The Nelson-Atkins picture Trouville, Beach Scene is a prime example of this subgenre. Boudin painted it in August 1874, a few months after participating in the inaugural Impressionist exhibition and one month after his fiftieth birthday. By that point in time, most of Boudin’s beach scenes were intended for a small circle of personal acquaintances.21Laurent Manœuvre, “Eugène Boudin’s Beach Scenes at the Salon during the 1860s,” Burlington Magazine 161, no. 1394 (May 2019): 374. The Nelson-Atkins panel was acquired from Boudin by Jean Théodore Elie Bullier (1831–1909), owner of a famous Parisian dance hall known as le bal Bullier, and it remained within his family for four generations.22Jean Théodore Elie Bullier succeeded his uncle François Bullier (1796–1869) as owner of le bal Bullier in 1869. Bruno Jarry, great-great-grandson of Jean Théodore Elie Bullier, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 29, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

Some critics, in an effort to assimilate Boudin into the narrative of

Impressionism, have overstated his desire to capture the effects of

light and atmosphere at Trouville and downplayed his interest in

studying high society.26Although Boudin befriended Claude Monet and exhibited with the Impressionists in 1874, he considered himself a loner who did not belong to a particular school: “Je n’eus point de maître à proprement parler; j’ai cherché tout seul sans être d’aucune coterie, d’aucune école.” Quoted in Cahen, Eugène Boudin, sa vie et son oeuvre, 133. Art columnist Dorothy Odenheimer, for

example, waxed poetic about Boudin’s treatment of “the prismatic dust of

sunlight and the filter of moist air” and claimed that the beachgoers in

his painting Approaching Storm (1864; Art Institute of Chicago) were

“merely a foil to set off the sky.”27Dorothy Odenheimer, “Boudin, Forerunner of Impressionism,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 33, no. 5 (September–October 1939): 79–80. Boudin was certainly attentive

to the nuances of weather, but he was also an astute observer of social

dynamics, and his figures often communicate much through small gestures.

In the Nelson-Atkins panel, the central group of bourgeois men and women

form a closed ring from which the nanny, children, and viewer are

excluded. One top-hatted gentleman stares pointedly at us, as if to

emphasize our interloper status. This unstinting gaze was a recurring

pictorial device for Boudin: many works depict one or more figures

looking squarely at the viewer.28See, for example, Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898, vol. 1, cats. 612, 619, 623, and 853. The Walters Art Museum’s

Trouville of 1871 (Fig. 6), for instance, shows several beachgoers

gazing directly at us, including the seated man at left, the woman in

yellow, and the servant with a hand on her hip. If their stares do not

amount to “legible anecdotal interchanges,” as art historian John House

put it, they do attest to Boudin’s skills of perception and his

curiosity about the socialites who flocked to Trouville.29House, “Boudin’s Modernity,” 19.

Notes

-

Léon Arbaud [Mme Lenormant], “Chronique du bord de la mer,” La Semaine des familles, no. 50 (September 12, 1863): 797–800. “J’étais au désespoir; à tout prix il me fallait sortir de cette prison de pierres, et je résolus de venir à Trouville. La cohue de voyageurs ahuris me prouva que je n’étais pas seul à ressentir l’impérieux besoin d’un peu d’air libre.” All translations by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

Vivien Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, exh. cat. (London: John Murray, 1992), 53.

-

Sylvie Gache-Patin and Scott Schaefer, “Impressionism and the Sea,” in Andrea P. A. Belloli, A Day in the Country: Impressionism and the French Landscape, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1984), 273–78. For a period rendering of Parisians jostling to board such a train, see Honoré Daumier, Les trains de plaisir, 1864, lithograph, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Rosenwald Collection, 1964.8.577.

-

Gustave Flaubert, Mémoires d’un fou: Roman (Paris: H. Floury, 1901), 63. “Ses maisons entassées les unes sur les autres, noires, grises, rouges, blanches, tournées de tous côtés, sans alignement et sans symétrie.” Flaubert wrote Mémoires d’un fou in 1838, but it was not published until 1901, some two decades after his death. For the Viking history of Trouville, see Adrienne Farrell, “Trouville, Normandy: Faces by Flaubert, Skies by Boudin,” New York Times (January 23, 1977).

-

Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, 78–80.

-

Jean-Louis Harouel, “From Francis I to Online Betting: The History of Gambling in France,” Pouvoirs 139, no. 4 (2011): 12.

-

As one period commentator put it: “En cinq heures et tout directement, Paris est à Trouville! C’est une heure de plus que pour Le Havre . . . mais on trouve sur la rive du Calvados une délicieuse plage de sable fin, au lieu de ce terrible galet qui roule là-bas tant d’entorses sous vos pieds, quand, agité par le flot, il ne vous bombarde les jambes de projectiles au moins incommodes et souvent inquiétants.” See “Courier de Paris,” Le Monde illustré, no. 333 (August 29, 1863): 130–31.

-

Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, 55.

-

Boudin commemorated the Empress’s excursion in a painting; see The Burrell Collection, Glasgow, no. 35.45. For the ambassador’s visit, see “Courier de Paris,” 130.

-

Georges Jean-Aubry, Eugène Boudin d’après des documents inédits: L’Homme et l’œuvre (Paris: Editions Bernheim-Jeune, 1922), 51. Other artists who painted at Trouville include Jules Achille Noël (1815–81), Richard Parkes Bonington (1802–1828), Louis Alexandre Dubourg (1821–91), Charles Louis Mozin (1806–62), and Charles François Pécrus (1826–1907).

-

Gustave Cahen, Eugène Boudin, sa vie et son oeuvre (Paris: H. Flory, 1900), 113. These studies likely served as aide-mémoires for his oil paintings.

-

John House, “Boudin’s Modernity,” in Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, 16.

-

For more on this gallery, see Monique Nonne, “Alfred Cadart (1828–1875), marchand de tableaux modernes,” Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art français (2009): 363–73.

-

Michael Clarke, “Boudin: Le Havre,” Burlington Magazine 158, no. 1364 (November 2016): 921.

-

Its paper support is mounted, so any extant verso inscriptions about its location are obscured from view. See technical notes by Nancy Heugh, Heugh-Edmondson Conservation Services, February–June 2016, NAMA conservation files.

-

For Boudin’s lodgings, see Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, 60. For the paintings in question, see Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898, vol. 1 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), cats. 261 and 272. Richard R. Brettell wrongly asserted that “None of the numerous beach paintings done in Deauville and Trouville in the mid-1860s has a horse and rider.” See Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 41.

-

For examples of horses pulling bathing cabins, see Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898, vol. 1, cats. 271, 275, and 294.

-

See technical notes by Nancy Heugh, Heugh-Edmondson Conservation Services, February–June 2016, NAMA conservation files.

-

Brettell and Pissarro, Manet to Matisse, 38.

-

Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, 64.

-

Laurent Manœuvre, “Eugène Boudin’s Beach Scenes at the Salon during the 1860s,” Burlington Magazine 161, no. 1394 (May 2019): 374.

-

Jean Théodore Elie Bullier succeeded his uncle François Bullier (1796–1869) as owner of le bal Bullier in 1869. Bruno Jarry, great-great-grandson of Jean Théodore Elie Bullier, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 29, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Boudin painted several studies of nursemaids, including La Nourrice sur la plage, ca. 1883–87, oil on panel, 5 3/4 x 9 1/4 in. (14.5 x 23.5 cm), sold by Pandolfini at the Palazzo Ramirez-Montalvo in Florence on November 23, 2016. See “Town, Country and Lady,” Bbys Magazine, November 20, 2016, https://www.barnebys.co.uk/blog/town-country-and-lady.

-

Quoted in Jean-Aubry, Eugène Boudin d’après des documents inédits, 190. “Dans ses tableaux, il aime les groupes, il représente la foule dense et remuante, plus volontiers que l’individu.”

-

Neurdein frères was a major photographic enterprise and publishing house active from 1863 to 1918. Run by Étienne (1832–1918) and Louis-Antonin (before 1840–after 1912) Neurdein, the business employed more than one hundred people, including several uncredited “operators” who handled the camera equipment. See Marie-Ève Brouillon, “Photographes et opérateurs: Le travail des Neurdein frères (1863–1918),” Mil neuf cent, no. 36 (2018): 95–114.

-

Although Boudin befriended Claude Monet and exhibited with the Impressionists in 1874, he considered himself a loner who did not belong to a particular school: “Je n’eus point de maître à proprement parler; j’ai cherché tout seul sans être d’aucune coterie, d’aucune école.” Quoted in Cahen, Eugène Boudin, sa vie et son oeuvre, 133.

-

Dorothy Odenheimer, “Boudin, Forerunner of Impressionism,” Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago 33, no. 5 (September–October 1939): 79–80.

-

See, for example, Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898, vol. 1, cats. 612, 619, 623, and 853.

-

House, “Boudin’s Modernity,” 19.

Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865, 2015.13.2

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.602.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.602.2088.

Eugène Boudin (1824–98) was the most skilled plein-airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio. pastellist of his generation. By his mid-40s he had completed so many studies of skies, sea, and beaches that he could quickly lay down an image that accurately described the weather and time of day. The Beach is an example of one of Boudin’s quickly executed, but studied, sea and shoreline paintings, in which he captures the pastimes of a windy day and realistically records the cool tones of the sand, water, and sky.

Similar to his use of ébaucheébauche: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called underpainting. for oil paintings,2Virginia Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)” (Postgraduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings, Final Year Project, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2018), 18–21. the major elements of the seascape, the sky with the clouds, the water in the middle ground, and the beach and foreground were laid in with blue, white, green, beige, and pink. Boudin frequently used the broad side of pastel sticks. The sea was blended at left so that the green and dark blue pastel applications mix. However, in the right half of the scene, the pastel strokes were applied on top of each other to create the impression of a sandbar or other features of the shallows. The colors of the beach were initially blended, with strokes of gray, yellow, light blue, and brown likely added at the end of the painting process to give the sand some relief. The painting is dominated by the figures in the foreground, and the paper below the horse and rider and the two women was left blank, with no evidence of either an underdrawing or an applied undertone.

Boudin did not use a fixative, although it would have aided him when he layered the sailboat and the figure in the blue coat over the underlayers of pastel.

Most of the elements in the image are in motion. The horse is mid-prance; the rider turns his head toward the women who lean forward in conversation; the man in orange walks along the shore; and the figure in blue appears to be headed in the direction of the artist. The clouds and the sailboat are being pushed out of the picture frame by the wind. Boudin was able to record the scene with rapidity because he had substantial practice. According to Charles Baudelaire, who saw sketches by the artist in 1859, Boudin made numerous tiny drawings of the sky, sea, and shore and annotated the margins of the drawings with date, time, and weather. Of these drawings, Baudelaire stated:

If you sometimes have the leisure to get to know these meteorological beauties, you could check, by memory, the accuracy of Mr. Boudin’s observations. You could hide the caption with your hand and you will easily guess the season, the time, and the wind. I am not exaggerating.3Œuvres Complètes de Charles Baudelaire, ed. F. F. Gautier (Paris: Éditions de la Nouvelle Revue Française, 1925), 307, <https://www.google.com/books/edition/OEuvres_compl%C3%A8tes_de_Charles_Baudelaire/zrnwAAAAMAAJ>. “Si vous avez eu quelquefois le loisir de faire connaissance avec ces beautés météorologiques, vous pourriez vérifier par mémoire l’exactitude des observations de M. Boudin. La légende cachée avec la main, vous devineriez, la saison, l’heure et le vent. Je n’exagère rien.” Any mistakes or inconsistencies in the translation are the fault of the author.

Although the pastel does faithfully record a morning or afternoon on a windy day, probably in the late summer, any inscription was lost when the edges of the artwork were cut down after the work was executed. A two-centimeter-long cut parallel to the right edge occurs immediately after the signature. The cut was made with a sharp blade and appears to be very old. The upper corners of the sheet are missing, and there are three pin or tack holes present along the upper edge at left. The holes appear to have been made later and do not indicate that the pastel was attached to a board during execution.

The work is currently edge-mounted to a late twentieth-century cream laid paper, and the back is not available for examination. There is evidence of at least two other mounting campaigns. During one, the artwork was attached to a window mat with gummed linen tape applied to the back of the artwork. Before that, brown paper tape was applied to the front edges of the artwork. Removal of the brown tape from the first matting campaign apparently resulted in image loss along the lower left and lower edges. To make the artwork look undamaged, the losses were covered with a yellow beige pastel which does not quite match the tones Boudin used for the sand.

Notes

-

The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

Virginia Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)” (Postgraduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings, Final Year Project, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2018), 18–21.

-

Œuvres Complètes de Charles Baudelaire, ed. F. F. Gautier (Paris: Éditions de la Nouvelle Revue Française, 1925), 307, https://www.google.com/books/edition/OEuvres_ compl%C3%A8tes_de_ Charles_Baudelaire /zrnwAAAAMAAJ.

“Si vous avez eu quelquefois le loisir de faire connaissance avec ces beautés météorologiques, vous pourriez vérifier par mémoire l’exactitude des observations de M. Boudin. La légende cachée avec la main, vous devineriez, la saison, l’heure et le vent. Je n’exagère rien.” Any mistakes or inconsistencies in the translation are the fault of the author.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.602.4033

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

With Galerie Cadart et Luquet, Paris, by October 15, 1867 [1];

Hembert collection, Paris;

With Raphaël Gérard, Paris, by 1963 [2];

With Rogers and Co., by December 7, 1966 [3];

Purchased from Rogers and Co. at Barbizon and Nineteenth-Century Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, Sotheby’s, London, December 7, 1966, lot 98, as La Plage à Trouville, by H. M. Cohen, 1966 [4];

With Galerie Schmit, Paris, by February 17, 1981–March 26, 1981 [5];

Purchased from Galerie Schmit by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, March 26, 1981–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] Alfred Cadart (1828–75) and Jules Joseph Luquet (b. 1824) formed a partnership in October 1863. They published etchings and operated a gallery together at 79 rue de Richelieu until October 15, 1867, when they dissolved their partnership. In November 1867, Cadart went into business with Léandre Luce at 58 rue Neuve-des-Mathurins. See Monique Nonne, “Alfred Cadart (1828–1875), marchand de tableaux modernes,” Bulletin de la Société de l’Histoire de l’Art français (2009): 363–73; and Janine Bailly-Herzberg, L’Eau-forte de peintre au dix-neuvième siècle: La Société́ des Aquafortistes, 1862–1867, vol. 1 (Paris: Leonce Laget, 1972), 252.

[2] Raphaël Louis Félix Gerard (1886–1963) passed away in 1963.

[3] For confirmation that the dealer “Rogers and Co.” consigned The Beach to Sotheby’s, see email from Carly Murphy, Sotheby’s, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, September 17, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. The consignor may have been T. Rogers and Co. Ltd, London, a packing and shipping agency that sometimes sold pictures at auction on behalf of clients. However, the records of T. Rogers and Co. do not extend back to the 1960s, so it has not been possible to confirm this identification; see email from Wil Russell, T. Rogers and Co., to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, October 15, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] For confirmation that H. M. Cohen purchased The Beach, see email from Carly Murphy, Sotheby’s, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, September 17, 2020, NAMA curatorial files. Murphy did not know Cohen’s full name or city of residence.

[5] See email from Robert Schmit, Galerie Schmit, to Henry Bloch, February 17, 1981, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

Eugène Boudin, Women in Crinolines on the Beach, 1865, watercolor on paper, 6 1/8 x 10 7/16 in. (15.5 x 26.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Watercolours and Sculpture (Part II) (London: Christie’s, November 29, 1994), 9.

Eugène Boudin, Two Riders on the Beach, ca. 1864–68, pastel on paper laid down on paper, 7 1/8 x 10 3/4 in. (18.1 x 27.3 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Works on Paper and Day Sales (New York: Christie’s, November 12, 2019), 98.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville Beach, ca. 1862–65, oil on panel, 8 1/2 x 14 in. (21 x 35.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 261, p. 1:83.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville Beach, ca. 1862–65, oil on panel, 8 1/2 x 14 in. (21 x 35.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Vivien Hamilton, Boudin at Trouville, exh. cat. (London: John Murray, 1992), 62.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

Regards sur une collection: XIXe–XXe siècles, Galerie Schmit, Paris, May 13–July 18, 1981, no. 5, as Sur la plage de Trouville.

The Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June–August 1982, no cat.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 3, as The Beach (La plage).

Painters and Paper: Bloch Works on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 20, 2017–March 11, 2018, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, The Beach, ca. 1865,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.602.4033.

Catalogue of Part I, Barbizon and Nineteenth-Century Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, and Part II, Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture (London: Sotheby’s, December 7, 1966), 30–31, (repro.), as La Plage à Trouville.

Art Prices Current: A Record of Sales Prices at the Principal London, Continental, and American Auction Rooms, vol. 44, August 1966 to July 1967 (Havant, England: Art Trade Press, 1968), A66, A294, as La Plage à Trouville.

Regards sur une collection: XIXe–XXe siècles, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1981), unpaginated, (repro.), as Sur la plage de Trouville.

“Exhibitions,” Gallery Events (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) (June–August 1982): unpaginated.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 3 (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 6 (June 2006): 61.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 14, 38–41, 43, 94, 110, 155, (repro.), as The Beach (La plage).

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 269 (June 3, 2007): E4.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11–12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

Alice Thorson, “Blochs add to Nelson treasures,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 141 (February 5, 2010): A1.

Carol Vogel, “O! Say, You Can Bid on a Johns,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174–75.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch gift to go for Nelson upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (July 31, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XnKATqhKiUk.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 88, (repro.), as The Beach.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 161 (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hecht, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go On Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 5D, (repro.), as The Beach.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017), http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/ article137040948.html [repr. “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries Feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr. in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” Blouin ArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/ 2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Megan McDonough, “Henry Bloch, whose H&R Block became world’s largest tax-services provider, dies at 96,” Washington Post (April 23, 2019): https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/henry-bloch-whose-handr-block-became-worlds-largest-tax-services-provider-dies-at-96/2019/04/23/19e95a90-65f8-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Artforum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” NPR (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr. Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 2015.13.4

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” technical entry in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.603.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.603.2088.

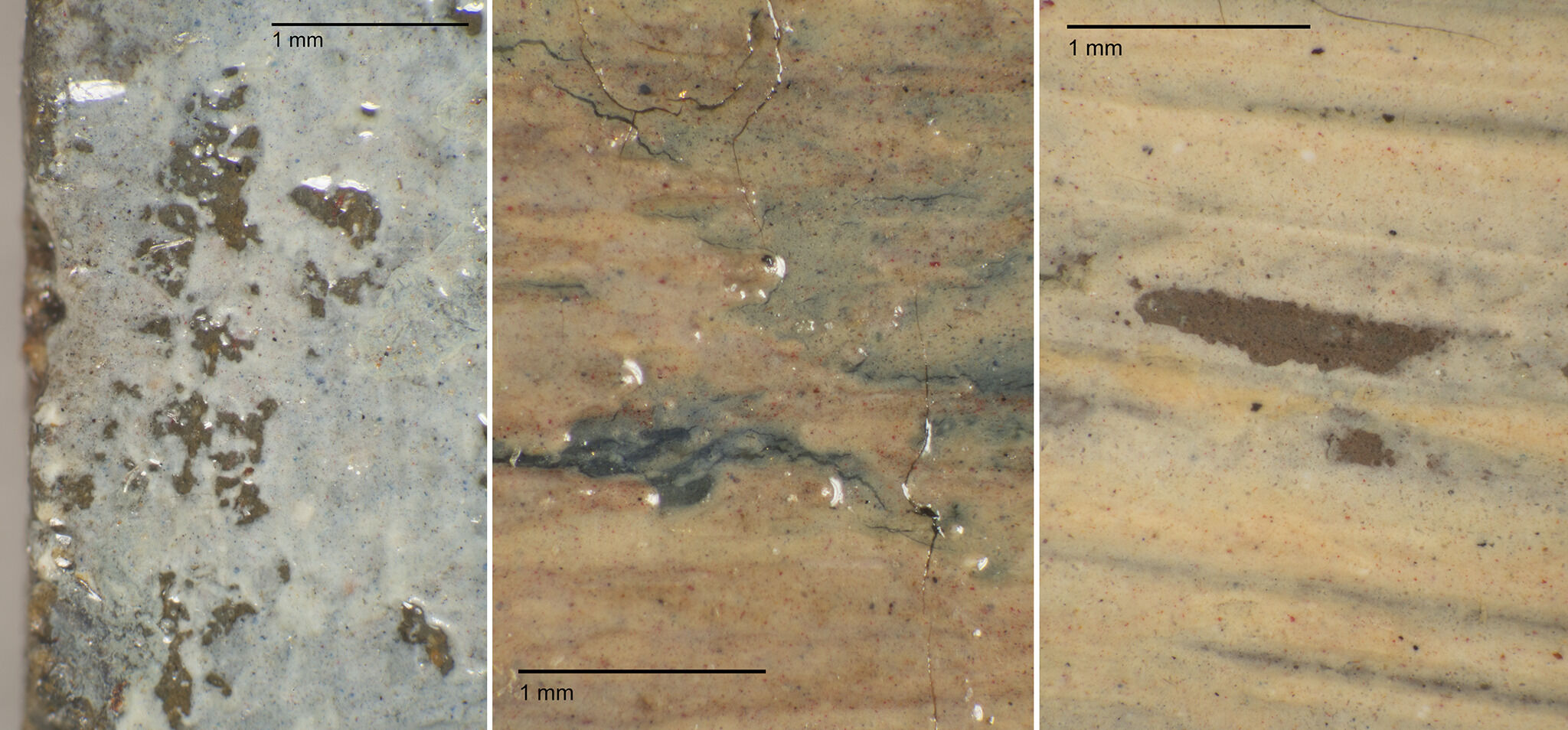

Trouville, Beach Scene was completed on wood panel, approximately five millimeters in thickness and beveled on the top and bottom verso edges. The format of this painting does not correspond with a standard sizestandard-format supports: Commercially prepared supports available through art suppliers, which gained popularity in the nineteenth century during the industrialization of art materials. Available in three formats figure (portrait), paysage (landscape), and marine (marine), these were numbered 1 through 120 to indicate their size. For each numbered size, marine and paysage had two options available: a larger format (haute) and smaller (basse) format. but is similar in size to other panels completed by Boudin.1Documentation of Boudin’s painting supports has shown that he employed both standard- and nonstandard-size supports. See Lara Broecke, “Notes on the Technique of Eugène Boudin,” Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, no. 4 (2013): 50. With no supplierartist supplier(s): Also called colormen and color merchants. Artist suppliers prepared materials for artists. This tradition dates back to the Medieval period, but the industrialization of the nineteenth century increased their commerce. It was during this time that ready-made paints in tubes, commercially prepared canvases, and standard-format supports were available to artists for sale through these suppliers. It is sometimes possible to identify the supplier from stamps or labels found on the reverse of the artwork. See also canvas stamp, supplier mark, and *color merchant. markings on the panel’s reverse, it is unclear where Boudin acquired this support, as he is known to have purchased his materials from a variety of sources.2Suppliers included artists’ colormen, marchands de malles (trunk-salesmen), and carpenters. Virginia Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)” (Postgraduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings, Final Year Project, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2018), 7-8. Small in size, panels such as these were often used for painting en plein airen plein air (adjective: plein-air): French for “outdoors.” The term is used to describe the act of painting quickly outside rather than in a studio. and could be completed quickly, capturing a moment of everyday life.

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph revealing lower sky layer beneath female figure, Trouville, Beach Scene (1874)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph revealing lower sky layer beneath female figure, Trouville, Beach Scene (1874)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of bow on standing girl, Trouville, Beach Scene (1874)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of bow on standing girl, Trouville, Beach Scene (1874)

Fig. 15. Detail illustrating a brushstroke from the sky slightly overlapping the figure’s head, causing wet-over-wet application within the hat, Trouville, Beach Scene (1874)

Fig. 15. Detail illustrating a brushstroke from the sky slightly overlapping the figure’s head, causing wet-over-wet application within the hat, Trouville, Beach Scene (1874)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of parasol ferrule pentimento, Trouville, Beach Scene (1874)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of parasol ferrule pentimento, Trouville, Beach Scene (1874)

Notes

-

Documentation of Boudin’s painting supports has shown that he employed both standard- and nonstandard-size supports. See Lara Broecke, “Notes on the Technique of Eugène Boudin,” Hamilton Kerr Institute Bulletin, no. 4 (2013): 50.

-

Suppliers included artists’ colormen, marchands de malles (trunk-salesmen), and carpenters. Virginia Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)” (Postgraduate Diploma in the Conservation of Easel Paintings, Final Year Project, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, 2018), 7–8.

-

No samples were taken during this examination. It is possible that a ground layer is present; however, this layer could not be identified through microscopy. Boudin often used commercially prepared supports with light-colored grounds. Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898),” 14–15.

-

Iris Schaefer, Caroline von Saint-George, and Katja Lewerentz, Painting Light: The Hidden Techniques of the Impressionists (Milan: Skira, 2008), 53.

-

Similar underpaintings have been identified on paintings in the collection of The National Gallery of London. Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898),” 18.

-

Nouwen, “An Investigation into the Materials and Techniques of Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898),” 19–20.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.603.4033

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

Acquired from the artist by Jean Théodore Elie Bullier (1831–1909), Paris, by 1898–October 26, 1909 [1];

Given to his granddaughter, Emma Jarry (née Marchand, 1888–1982), Paris, October 26, 1909–no later than April 7, 1982 [2];

By descent to her daughter, Madeleine-Françoise Jarry (1917–1982), Paris, by April 7, 1982–June 29, 1982 [3];

Inherited by her brother, Pierre Jarry (1913–1999), Paris, June 29, 1982–November 27, 1984 [4];

Purchased from Jarry by Adolphe Stein, Paris, on joint account with Richard Green, London, stock no. RH 594, November 27, 1984–February 1985 [5];

Half-share purchased from Adolphe Stein by Richard Green, February 1985–November 13, 1985 [6];

Purchased from Richard Green by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, November 13, 1985–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] Boudin sold or gifted the painting to Bullier at an unknown date, but certainly before his death in 1898. The owner of a famous Parisian dance hall, Bullier had a wide circle of acquaintances that included many artists. See email from Bruno Jarry, great-great-grandson of Jean Théodore Elie Bullier, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 29, 2020, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] Jean Théodore Elie Bullier’s daughter, Ernestine Françoise Bullier (1866–1942), married Gustave Honoré-Léon Raoul Marchand (1875–1935) on July 4, 1887. Their daughter, Emma Marchand, received the painting as a wedding gift from her grandfather when she married Paul Jarry (1883–1934) on October 26, 1909, three weeks before her grandfather’s death. See emails from Bruno Jarry to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 29, 2020 and January 25, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] It is unclear precisely when Emma Jarry bequeathed Trouville, Beach Scene to her daughter, but she did so prior to her death on April 7, 1982. The two women shared an apartment in Paris beginning in 1946, and the painting remained on view in their salon until Madeleine-Françoise Jarry’s death on June 29, 1982, only a few months after her mother’s passing. See emails from Bruno Jarry to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 29, 2020 and January 25, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[4] Pierre Jarry, a resident of Marseille, inherited his sister’s apartment and belongings, including Trouville, Beach Scene, upon her death. The painting remained in Paris until its sale in 1984. See emails from Bruno Jarry to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, January 25–26, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[5] Jarry received payment for the painting on November 27, 1984, but it took several months for the export license to receive approval. See email from Bruno Jarry to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 29, 2020, and letter from M. Jacot, International Art Transport, to Pierre Jarry, July 10, 1985, NAMA curatorial files. Richard Green stock number from verso label.

[6] For the purchase date of February 1985, see email from Penny Marks, Richard Green, to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, April 21, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 7 1/4 x 14 in. (18.5 x 35.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Anne-Marie Bergeret-Gourbin et al., Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898, exh. cat. (Honfleur: Association “Eugène Boudin-Honfleur 92,” 1992), 226.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 6 1/2 x 14 in. (16.7 x 35.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 939, p. 1:335.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 7 1/4 x 14 1/4 in. (18.5 x 36 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 940, p. 1:336.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 6 1/2 x 10 7/8 in. (16.5 x 27.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 941, p. 1:336.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 6 1/4 x 11 1/2 in. (16 by 29.4 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (London: Sotheby’s, February 8, 2012), 205.

Eugène Boudin, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 7 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. (17 x 35.2 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Art: Works on Paper and Day Sale; Including Property from the Estate of Edgar M. Bronfman (New York: Christie’s, May 7, 2014), unpaginated.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 7 1/2 x 13 in. (19 x 33.2 cm), location unknown, cited in in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 944, p. 1:337.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 7 7/8 x 13 1/16 in. (20 x 33 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Drawings: From the Collection of the Late Gisèle Rueff-Béghin (London: Sotheby’s, November 29, 1988), unpaginated, as Scène de plage à Trouville.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 6 3/4 x 13 3/4 in. (17 x 35 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 946, p. 1:337.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 4 3/4 x 10 5/8 in. (12 x 27 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 947, p. 1:337.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 6 3/4 x 13 7/8 in. (17.1 x 35.2 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Art: Works on Paper and Day Sale (London: Christie’s, February 28, 2018), 235.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, 9 1/4 x 12 3/8 in. (23.5 x 31.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898 (Paris: Galerie Schmit, 1973), no. 950, p. 1:338.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 6 3/4 x 14 in. (17.1 x 35.6 cm), location unknown, cited in Impressionist and Modern Art Day Sale (New York: Christie’s, November 6, 2008), 101.

Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874, oil on panel, 5 3/8 x 11 5/8 in. (13.5 x 29.5 cm), location unknown, cited in Robert and Manuel Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898: Deuxième supplément (Paris: Éditions Galerie Schmit, 1993), no. 3920, p. 28.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 4, as Trouville, Beach Scene (Trouville, scène de plage).

Magnificent Gifts for the 75th, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 13–April 4, 2010, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation in ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Eugène Boudin, Trouville, Beach Scene, 1874,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2021. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.603.4033.

Robert and Manuel Schmit, Eugène Boudin, 1824–1898: Deuxième supplément (Paris: Éditions Galerie Schmit, 1993), no. 3919, pp. 28, 182–84, (repro.), as Trouville. Scène de plage.

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 3 (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 6 (June 2006): 61.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 14, 38, 42–43, 110, 155, (repro.), as Trouville, Beach Scene (Trouville, scène de plage).

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 269 (June 3, 2007): E4.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 11–12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

Alice Thorson, “Blochs add to Nelson treasures,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 141 (February 5, 2010): A1, A8.

Carol Vogel, “O! Say, You Can Bid on a Johns,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174–75.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch gift to go for Nelson upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art officially accessions Bloch Impressionist masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (July 31, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017-.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XnKATqhKiUk.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 57, (repro.), as Trouville, Beach Scene.

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 161 (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hecht, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go On Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 5D, (repro.) as Trouville, Beach Scene.

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017): http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/ article137040948.html [repr. “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/.

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries Feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/.

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr. in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20–22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” Blouin ArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/ 2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times (April 23, 2019): https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/23/obituaries/henry-w-bloch-dead.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922-2019),” Artforum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” NPR (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr. Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.