Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Sarah Catala, “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.330.5407.

MLA:

Catala, Sarah. “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.330.5407.

Long thought to be a view of the terraces of the Château de Marly, this painting remains a purposeful mystery. While there is no doubt that this is the work of Hubert Robert, the interpretation of its subject, proposed by various commentators over the last century, deserves to be revisited. When the painting was exhibited to the public in Paris in 1928, it was presented under the evocative title View from Marly Toward Saint-Germain-en-Laye. However, Marly’s gardens did not include elevated terraces with views of a neighboring valley, as seen in this painting. Quite to the contrary, Marly is nestled in the hollow of a valley, where it was a favorite retreat for Louis XIV and his court. Behind the estate was the “Marly Machine,” used to supply water to the Marly fountains as well as the château and gardens of Versailles. The Marly Machine was also within sight of the old and new châteaux of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. However, the château depicted by Robert does not correspond to either the new château (destroyed in 1810) or the old one, which today houses the National Museum of Archaeology. Finally, although the painting’s title had included the word “Marly” since at least 1928, the Nelson-Atkins Museum retitled it in 2022, during the preparation of this catalogue, in order to acknowledge its invented nature.1The title in 2022 was Imaginary View of the Terrace at the Château of Marly. For the painting’s relationship to Marly, see Sarah Catala, Hubert Robert: De Rome à Paris, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Éric Coatalem, 2021), 46. This revision not only addresses the complexity of connecting the painting to Robert’s documented views of Marly but also positions it within the tradition of capriccio, or architectural fantasy. Robert was an undisputed master of this genre in France during the second half of the eighteenth century.

Accepted into the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1766 as

an architectural painter, Robert also taught landscape drawing to

wealthy amateurs before being appointed Keeper of the King’s Paintings

in 1778 and then Designer of the King’s Gardens in 1784. From the

beginning, he transformed the locations that he painted, adding famous

sculptures to flatter the tastes of his clients, who first included

Grand TourGrand Tour: An extended tour of Europe, in particular Italy, in the eighteenth century, taken by wealthy young men (and some women), especially British and American ones, to complete their education and cultivation. collectors and then the financial elite gathered around the

powerful Duc de Choiseul. In 1775, Robert’s first garden view exhibited

at the SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. depicted those of the Château de Gaillon, a perfect

architectural example of the transition between medieval and Renaissance

art in France, which was then an interest of Robert’s.2Hubert Robert, Vue du Château de Gaillon in Normandy, ca. 1775, oil on canvas, 165 3/8 x 126 in. (420 x 320 cm), Salle des Etats, Palais archiépiscopal de Rouen. For an overall image of the painting as well as it in situ in the Salle des Etats (on the far left), see “Rouen, le Palais de l’Archevêché,” Patrimoine-Histoire, accessed September 2, 2025, https://www.patrimoine-histoire.fr

In 2016, Yuriko Jackall inventoried Robert’s paintings of Marly

exhibited at the Salon and sold in the eighteenth century, but she found

no parallel to the Kansas City painting or to the lone extant documented

view by Robert of Marly, now in the State Hermitage Museum in Saint

Petersburg (Fig. 1).6See Yuriko Jackall’s entry on the Nelson-Atkins painting, in Margaret Morgan Grasselli and Yuriko Jackall, Hubert Robert, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2016), 237–38, cat. 70. I contend, however, that the Saint Petersburg

painting is probably the one mentioned in the catalogue for a sale of

works owned by the sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741–1828) in 1795 and

immediately acquired by Prince Nikolai Borisovich Yusupov, a Russian

nobleman and statesman.7The painting is described in the Houdon sale: “Vue intérieure du Parc de Marly. Ce tableau, orné de figures, est touché avec l’esprit et la facilité ordinaire aux ouvrages de cet artiste. Hauteur 24 pouces, largeur 32 pouces” (Interior view of the Marly Park. This painting, decorated with figures, exhibits the spirit and facility typical of this artist’s works. Height 24 inches, width 32 inches). See Catalogue de quelques tableaux, peints par le Bourguignon, Oudry; Danlos du cabinet du C.en Houdon, sculpteur (Paris: F. L. Regnault, October 8, 1795), 5, no. 5. While the height of the Saint Petersburg painting differs by five centimeters from the description in the Houdon sale catalogue, this change probably corresponds to the upper edge of the canvas being trimmed, where today we see that the tops of the trees are cut off. The painting owned by Houdon may have been part of the payment for a posthumous bust of Robert’s eldest daughter that Houdon exhibited at the Salon of 1783. See Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures (1783), 48, no. 244. Very early on, Robert adopted the habit of

capitalizing on the popularity of compositions he first exhibited at the

Salon (like those of Marly) and providing variants for his loyal

clients, particularly those who were committed to the development of the

arts in France.8This is addressed in Sarah Catala, “Démarches d’incitation,” in “Hubert Robert et le temps de la citation” (PhD diss., University of Lyon Lumière 2, 2020), 211–60. See also Yuna Blajer de la Garza, “A House Is Not a Home: Citizenship and Belonging in Contemporary Democracies” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2019). We can intuit from the Salon booklets that the

series of views they described as of Marly probably depicted the

promenade and the sculpture area in the gardens. Although the other

versions are lost, a compositional link can be inferred through the

sculptures depicted in the Saint Petersburg painting, which features the

equestrian group the Marly Horses by Guillaume Coustou the elder

(1677–1746), and the Nelson-Atkins painting, which shows Mercury

Fastening His Sandal by Jean-Baptiste Pigalle (1714–85), both

associated with the paintings that have come to be known as Robert’s

“Marly series.”9The marble sculpture group Marly Horses was installed at Marly in 1745 but is now located in the Cour Marly in the Musée du Louvre in Paris: Guillaume Coustou the elder, Marly Horses, 1745, Carrara marble, 133 7/8 x 111 13/16 x 50 in. (340 x 284 x 127 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, MR 1803, https://collections.louvre.fr

Fig. 2. Hubert Robert, Figures in a Park Bordered by an Overhanging Balustrade, ca. 1775, black chalk on laid paper, 4 9/16 x 3 1/2 in. (11.6 x 8.8 cm), Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 11567, recto

Fig. 2. Hubert Robert, Figures in a Park Bordered by an Overhanging Balustrade, ca. 1775, black chalk on laid paper, 4 9/16 x 3 1/2 in. (11.6 x 8.8 cm), Département des Arts graphiques, Musée du Louvre, Paris, RF 11567, recto

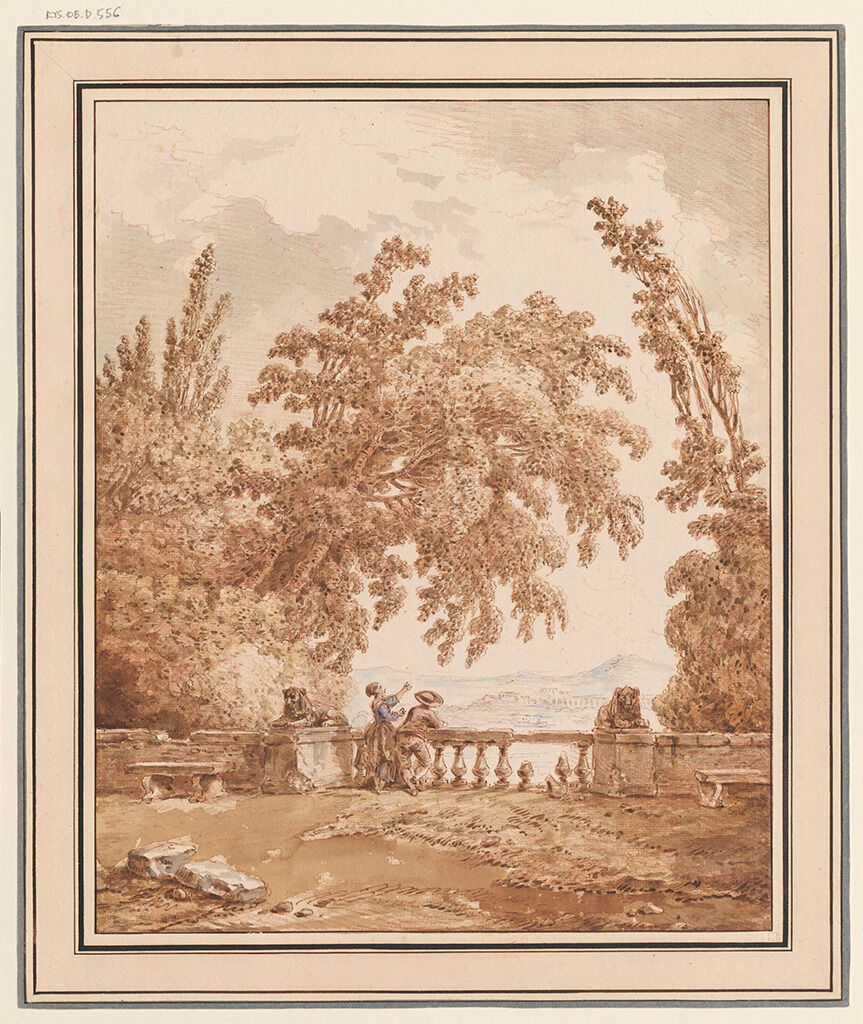

Fig. 3. Hubert Robert, Terrace of an Italian Villa, ca. 1765, watercolor, brown ink, and red chalk counterproof on laid paper, 13 15/16 x 11 7/16 in. (35.5 x 29 cm), National Museum, Warsaw, acc. no. Rys.Ob.d.556 MNW

Fig. 3. Hubert Robert, Terrace of an Italian Villa, ca. 1765, watercolor, brown ink, and red chalk counterproof on laid paper, 13 15/16 x 11 7/16 in. (35.5 x 29 cm), National Museum, Warsaw, acc. no. Rys.Ob.d.556 MNW

Both paintings reveal the artist’s careful attention to the overall

composition along with his painstaking study of details. A black chalk

sketch from early in Robert’s artistic process, preserved in a notebook

in the Musée du Louvre (Fig. 2), depicts a couple in a low, horizontal

foreground near a stone balustrade, standing before a distant valley.

This view echoes the experience that visitors on the Grand Tour had when

discovering the Tivoli Gardens in Lazio, Italy, overlooking the Aniene

River Valley and the Apennine Mountains. Robert reworked the composition

in a red chalk drawing, which has been lost, but its counterproof,

enhanced with watercolor, is at the National Museum in Warsaw (Fig.

3).10The red chalk lines, from top to bottom and from right to left, indicate an inversion of the direction of Robert’s composition, since he was right-handed. It is not certain whether it was enhanced by the artist himself. Robert modeled this composition on the Louvre drawing but

elaborated the couple further, showing them contemplating the vista

while the woman points to a monument visible in the valley beyond.

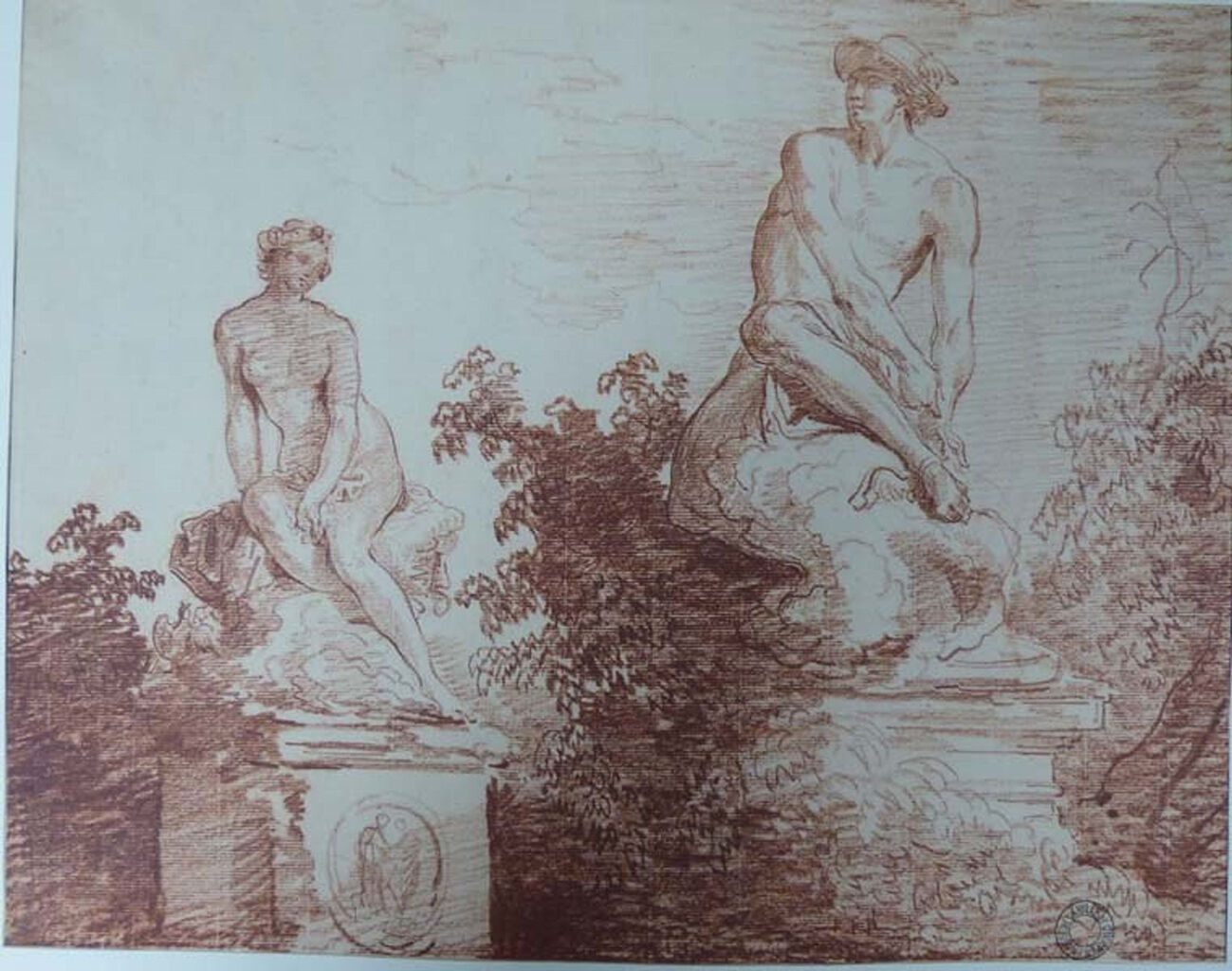

Robert expanded this idea in the Nelson-Atkins painting by integrating

three elegant women, previously sketched in isolation with black chalk

on paper (Fig. 4), as well as Pigalle’s statue of Mercury, which Robert

had previously drawn in red chalk (Fig. 5). He relied on his

imagination, rather than an accurate model, to draw the fountain with

the lion’s muzzle and the vases on the balustrade.11Robert often used these two motifs in his works. However, there is a particular affinity with a red chalk drawing at the Louvre, annotated “Ce 7 janvier 1773” (This January 7, 1773), which suggests that it was made during a drawing session with the aristocratic and financial circle of amateurs with whom Robert associated. See Jeune femme, tenant un panier, descendant des marches près d’une fontaine, 1773, red chalk on paper, 14 5/16 x 11 in. (36.4 x 27.9 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 28984, recto, https://arts-graphiques.louvre.fr

Fig. 4. Hubert Robert, Study for “Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château,” ca. 1775–80, black chalk on paper, 6 5/8 x 8 5/8 in. (16.8 x 21.9 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 55-81

Fig. 4. Hubert Robert, Study for “Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château,” ca. 1775–80, black chalk on paper, 6 5/8 x 8 5/8 in. (16.8 x 21.9 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 55-81

Fig. 5. Hubert Robert, Two Statues in a Park, 1765–70, red chalk drawing on fine cream laid paper, 11 7/16 x 14 1/2 in. (29 x 36.8 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Quimper, inv. no. 873-2-40

Fig. 5. Hubert Robert, Two Statues in a Park, 1765–70, red chalk drawing on fine cream laid paper, 11 7/16 x 14 1/2 in. (29 x 36.8 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Quimper, inv. no. 873-2-40

No inscription or known archival document provides a date for the

Nelson-Atkins painting, but comparison with other works helps to

establish a chronological range. As noted above, Robert presented two

medium-size landscapes inspired by Marly at the Salon of 1777 and two

small vertical sketches at the Salon of 1783.13Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures (1777), 16–18, nos. 76, 81, 82; Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures (1783), 18, no. 66. Unfortunately, these

works are lost.14We only know them through the descriptions in the Salon booklets; the extant works (see “related works” in this entry) do not match the dimensions and formats. However, we know that the period beginning in 1775

marked a turning point in Robert’s career, as he designed the layout of

his clients’ gardens and also depicted those same clients, surrounded by

nature, in his paintings: Élisabeth Louise de La Rochefoucauld, wife of

the future Duc de Rohan-Chabot, drawing in front of La Roche-Guyon (ca.

1775; Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen); and Pierre Jacques Onésyme Bergeret

and his mistress, Jeanne Viguier, renowned collectors and Grand Tour

travelers, in front of an immense landscape inspired by Tivoli and the

Alps, painted in 1779 (Fig. 6).15The paintings of Geoffrin, currently unlocated, are reproduced in Cayeux, Hubert Robert et les jardins, 120–24; the La Rochefoucauld painting is Hubert Robert, Vue du château de La Roche-Guyon, ca. 1775, oil on canvas, 76 3/4 x 108 11/16 in. (195 x 276 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, inv. 1909.37.1, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr

Searching Robert’s work for a perfectly faithful view of a place or a person is a futile task. Robert was neither a topographer nor a portraitist but an artist who inspired the imagination of his admirers, as when he painted the renovation of the gardens surrounding the Palace of Versailles in 1777 (Fig. 7). The composition of that work, a royal commission, recalls that of the Nelson-Atkins painting, with the foreground covering the entire bottom section of the canvas, pushing the view of nature into the background. Both canvases highlight female figures in the foreground and sculptures by French artists.16The sculptures in The Entrance to the Tapis Vert at Versailles (Fig. 7) are the work of Pierre Puget (1620–94).

Although he sketched sur le motifsur le motif: French for “in front of the object.” A term used for sketching or painting from life., Robert painted his final works in

his studio at the Louvre, where he combined aspects of studies, like

the Warsaw drawing, with compositions from fully realized paintings, like the one of

Versailles that he completed for the king. In the Bergeret painting (see

Fig. 6), he used a model (whose identity has not been established) for

the woman raising her arm, and for the Nelson-Atkins painting he

reversed and combined her with the sketch of three women (see Fig. 4).

Finally, he added the statue of Mercury, taken from the red chalk

drawing (see Fig. 5), which he had already used at least once before in

The Bathing Pool, painted for the Château de Bagatelle and

commissioned by the Comte d’Artois in 1777 (Metropolitan Museum of Art,

New York).17Hubert Robert, The Bathing Pool, ca. 1777–79, oil on canvas, 68 3/4 x 48 3/4 in. (174.6 x 123.8 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acq. no. 17.190.29, https://www.metmuseum.org

Apart from preliminary studies completed on site, Robert usually made a large painting first, often displaying it at the Salon, and later created reduced versions for private clients. Given the modest dimensions of the Saint Petersburg painting, it is likely that it was created after the Nelson-Atkins painting and may have been inspired by it.18For compositional reasons, this is also the hypothesis proposed by Ekaterina Deriabina in “Ruines d’une Terrasse dans le Parc de Marly,” in Hubert Robert (1733–1808) et Saint-Pétersbourg: Les commandes de la famille Impériale et des Princes russes entre 1773 et 1802, ed. Hélène Moulin, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999), 152. The proposed date range of both paintings seems to be reinforced by multiple links between them and the paintings mentioned above, dated from 1777 to 1779. All of them depict the need for rest during a walk, in order to relax with family or as a couple, and to indulge in the contemplation of nature and works of art in the gardens.

Robert generally worked on commission, but sometimes he took the liberty

of creating paintings tailored to his clients’ tastes on speculation,

without receiving a commission in advance.19As noted by Pierre de Nolhac, Hubert Robert, 1733–1808 (Paris: Goupil, 1910), 71–72, about a painting that Robert decided independently to paint for the artist Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny Damas, Marquise de Grollier (1741–1828). This painting, used as a mantelpiece, has dimensions that are very similar to those of the Nelson-Atkins painting: 92.5 x 126 cm. Today in a private collection, it is reproduced in Véronique Damian, L’Art au féminin: Portrait de la marquise de Grollier (1741–1828), par Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) (Paris: Galerie Canesso, 2018), 9. Because we can trace the

provenance of the Nelson-Atkins painting only to 1892, we can merely

speculate about the reasons for its creation. I propose that the

painting is a capriccio with Pigalle’s statue and a medieval château.

Robert may have wanted to refer to the relocation of a lead copy of the

Mercury statue—formerly the property of the Marquise de Pompadour—to the

garden of the Château d’Anet in 1775,20Since then held by the Musée du Louvre: Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Mercury Fastening His Sandal, 1753, lead, 73 5/8 x 42 1/2 x 41 3/4 in. (187.1 x 108 x 106 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 3023; see “Mercure attachant ses talonnières,” Ministère de la Culture, accessed September 2, 2025, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr

It is conceivable that this painting was intended for a wealthy woman from among Robert’s acquaintances. Here he takes the rare—and possibly unique—step of painting a pair of blue-and-white faience Medici vases filled with pink flowers. Robert rarely depicted flowers, instead giving priority to the order and colors of his compositions. Robert saturates the surface with shades of green, modulated by the lateral light and framed by ocher shades, darker for the ground and lighter for the clouds. The subtle angles—repeated in the spread of moss on the ground, the raised arm of the woman in white, the tree leaning to the left, and the ascending line of the hill—provide the viewer with an immersive effect. Robert presents a true mise en abyme (image within an image): a landscape being observed by women, who are themselves under the eye of a viewer with a broader vista of the scene. Robert also painted similarly scaled paintings for mantelpieces, perhaps with a wink of humor.22See De Nolhac, Hubert Robert, 71–72. Could the Nelson-Atkins painting allude to the idea of waiting by a fire during the wintertime, hoping to find oneself among friends during the long walks promised by spring?23This is a hypothesis based on the similarity of the painting’s format to the one Robert painted for the Marquise de Grollier (see n. 19), whose subject was entirely customized. According to Robert’s own description, the painting depicts a house on fire with people saving a floral still life by the Marquise. Without Robert’s letter to the Marquise, reproduced in De Nolhac, Hubert Robert, between pages 70–71, it would have been impossible to understand Robert’s economic strategies and artistic liberties. The painting is also reproduced as an engraving in De Nolhac, Hubert Robert, between pages 72 and 73.

The Nelson-Atkins painting reveals a new direction in Robert’s art after 1775 as he developed a rich dialogue among nature, his paintings, and his garden projects. While the painting cannot be linked definitively to Marly or any other specific château, it nevertheless remains an invaluable testament to Robert’s growing interest in the architecture marking the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance in France. It is precisely the discovery of this vernacular heritage, and how it became the object of fashionable promenades, that Robert depicts in this painting.

Notes

Translated from the original French by Nicole Halton and David Auerbach, courtesy of Eriksen Translations.

-

The title in 2022 was Imaginary View of the Terrace at the Château of Marly. For the painting’s relationship to Marly, see Sarah Catala, Hubert Robert: De Rome à Paris, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie Éric Coatalem, 2021), 46.

-

Hubert Robert, Vue du Château de Gaillon in Normandy, ca. 1775, oil on canvas, 165 3/8 x 126 in. (420 x 320 cm), Salle des Etats, Palais archiépiscopal de Rouen. For an overall image of the painting as well as it in situ in the Salle des Etats (on the far left), see “Rouen, le Palais de l’Archevêché,” Patrimoine-Histoire, accessed September 2, 2025, https://www.patrimoine-histoire.fr

/Patrimoine . See also Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale (Paris: Imprimerie de la Veuve Herissant, 1775), 15, no. 73./Rouen /Rouen -Archeveche.htm -

Sarah Catala and Gabriel Wick, eds., Hubert Robert et la Fabrique des Jardins, exh. cat. (Paris: RMN-Grand Palais, 2017), 21–22.

-

Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale (Paris: Imprimerie de la Veuve Herissant, 1777), 16–18, nos. 76, 81, 82; Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale (Paris: Imprimerie de la Veuve Herissant, 1783), 18, no. 66.

-

See Jean de Cayeux, Hubert Robert et les Jardins (Paris: Herscher, 1987). In the second half of the eighteenth century, particularly under Louis XV and Louis XVI, France experienced widespread enthusiasm for garden design. This was fueled by changing aesthetic tastes, scientific curiosity, and aristocratic competition, as royals and financiers vied to create increasingly refined and imaginative landscapes. Gardens like these required a great deal of money to be developed and maintained.

-

See Yuriko Jackall’s entry on the Nelson-Atkins painting, in Margaret Morgan Grasselli and Yuriko Jackall, Hubert Robert, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2016), 237–38, cat. 70.

-

The painting is described in the Houdon sale: “Vue intérieure du Parc de Marly. Ce tableau, orné de figures, est touché avec l’esprit et la facilité ordinaire aux ouvrages de cet artiste. Hauteur 24 pouces, largeur 32 pouces” (Interior view of the Marly Park. This painting, decorated with figures, exhibits the spirit and facility typical of this artist’s works. Height 24 inches, width 32 inches). See Catalogue de quelques tableaux, peints par le Bourguignon, Oudry; Danlos du cabinet du C.en Houdon, sculpteur (Paris: F. L. Regnault, October 8, 1795), 5, no. 5. While the height of the Saint Petersburg painting differs by five centimeters from the description in the Houdon sale catalogue, this change probably corresponds to the upper edge of the canvas being trimmed, where today we see that the tops of the trees are cut off. The painting owned by Houdon may have been part of the payment for a posthumous bust of Robert’s eldest daughter that Houdon exhibited at the Salon of 1783. See Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures (1783), 48, no. 244.

-

This is addressed in Sarah Catala, “Démarches d’incitation,” in “Hubert Robert et le temps de la citation” (PhD diss., University of Lyon Lumière 2, 2020), 211–60. See also Yuna Blajer de la Garza, “A House Is Not a Home: Citizenship and Belonging in Contemporary Democracies” (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2019).

-

The marble sculpture group Marly Horses was installed at Marly in 1745 but is now located in the Cour Marly in the Musée du Louvre in Paris: Guillaume Coustou the elder, Marly Horses, 1745, Carrara marble, 133 7/8 x 111 13/16 x 50 in. (340 x 284 x 127 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, MR 1803, https://collections.louvre.fr

/en (and see also its pendant sculpture, Guillaume Coustou the elder, Marly Horses, 1745, Carrara marble, 133 7/8 x 111 13/16 x 50 in. [340 x 284 x 127 cm], Musée du Louvre, Paris, MR1802, https://collections.louvre.fr/ark: /53355 /cl010091993 /en ). For the enlarged replica of Mercury (which was commissioned by King Louis XV to present to Frederick the Great of Prussia), see Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Mercury Fastening His Sandal, 1748, marble, 76 3/4 x 47 1/4 x 37 13/16 in. (195 x 120 x 96 cm), Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Bode-Museum, Berlin, no. 356, https://id.smb.museum/ark: /53355 /cl010091992 /object . For the smaller, original version, see Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Mercury Fastening His Sandal, 1744, marble, 22 13/16 x 14 x 13 in. (58 x 35.5 x 33 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, no. MR 1957, https://collections.louvre.fr/1368124 /merkur /en ./ark: /53355 /cl010092060 -

The red chalk lines, from top to bottom and from right to left, indicate an inversion of the direction of Robert’s composition, since he was right-handed. It is not certain whether it was enhanced by the artist himself.

-

Robert often used these two motifs in his works. However, there is a particular affinity with a red chalk drawing at the Louvre, annotated “Ce 7 janvier 1773” (This January 7, 1773), which suggests that it was made during a drawing session with the aristocratic and financial circle of amateurs with whom Robert associated. See Jeune femme, tenant un panier, descendant des marches près d’une fontaine, 1773, red chalk on paper, 14 5/16 x 11 in. (36.4 x 27.9 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 28984, recto, https://arts-graphiques.louvre.fr

/detail ./oeuvres /1 /228359 -Jeune -femme -tenant -un -panier -descendant -des -marches -pres -dune -fontaine -

As Charlotte Guichard has noted in other instances; see Charlotte Guichard, La Griffe du peintre, la valeur de l’art (1730–1820) (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2018), 151.

-

Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures (1777), 16–18, nos. 76, 81, 82; Explication des Peintres, Sculptures, et Gravures (1783), 18, no. 66.

-

We only know them through the descriptions in the Salon booklets; the extant works (see “related works” in this entry) do not match the dimensions and formats.

-

The paintings of Geoffrin, currently unlocated, are reproduced in Cayeux, Hubert Robert et les jardins, 120–24; the La Rochefoucauld painting is Hubert Robert, Vue du château de La Roche-Guyon, ca. 1775, oil on canvas, 76 3/4 x 108 11/16 in. (195 x 276 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, inv. 1909.37.1, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr

/notice ./joconde /07290022333 -

The sculptures in The Entrance to the Tapis Vert at Versailles (Fig. 7) are the work of Pierre Puget (1620–94).

-

Hubert Robert, The Bathing Pool, ca. 1777–79, oil on canvas, 68 3/4 x 48 3/4 in. (174.6 x 123.8 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acq. no. 17.190.29, https://www.metmuseum.org

/art ./collection /search /437473 -

For compositional reasons, this is also the hypothesis proposed by Ekaterina Deriabina in “Ruines d’une Terrasse dans le Parc de Marly,” in Hubert Robert (1733–1808) et Saint-Pétersbourg: Les commandes de la famille Impériale et des Princes russes entre 1773 et 1802, ed. Hélène Moulin, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1999), 152.

-

As noted by Pierre de Nolhac, Hubert Robert, 1733–1808 (Paris: Goupil, 1910), 71–72, about a painting that Robert decided independently to paint for the artist Charlotte Eustache Sophie de Fuligny Damas, Marquise de Grollier (1741–1828). This painting, used as a mantelpiece, has dimensions that are very similar to those of the Nelson-Atkins painting: 92.5 x 126 cm. Today in a private collection, it is reproduced in Véronique Damian, L’Art au féminin: Portrait de la marquise de Grollier (1741–1828), par Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) (Paris: Galerie Canesso, 2018), 9.

-

Since then held by the Musée du Louvre: Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Mercury Fastening His Sandal, 1753, lead, 73 5/8 x 42 1/2 x 41 3/4 in. (187.1 x 108 x 106 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 3023; see “Mercure attachant ses talonnières,” Ministère de la Culture, accessed September 2, 2025, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr

/notice . This interpretation follows the identification of the statue proposed by Jean-René Gaborit in Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, 1714–1785: Sculptures du Musée du Louvre (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1985), 45./joconde /M5037011602 -

The Château de Josselin is located in Brittany. Built between 1490 and 1505, with its Renaissance façade overlooking the courtyard and the l’Oust River, it is the seat of the aristocratic Rohan family. While the three towers were still in place in the eighteenth century, the keep and the gatehouse had been destroyed by 1762. The castle was renovated beginning in 1860. See “Josselin Castle, Place de la Congrégation (Josselin),” Ministère de la Culture, accessed September 2, 2025, https://pop.culture.gouv.fr

/notice ./merimee /IA00121519 -

See De Nolhac, Hubert Robert, 71–72.

-

This is a hypothesis based on the similarity of the painting’s format to the one Robert painted for the Marquise de Grollier (see n. 19), whose subject was entirely customized. According to Robert’s own description, the painting depicts a house on fire with people saving a floral still life by the Marquise. Without Robert’s letter to the Marquise, reproduced in De Nolhac, Hubert Robert, between pages 70–71, it would have been impossible to understand Robert’s economic strategies and artistic liberties. The painting is also reproduced as an engraving in De Nolhac, Hubert Robert, between pages 72 and 73.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Susan Pavlik Enterline, “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.330.2088.

MLA:

Enterline, Susan Pavlik. “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.330.2088.

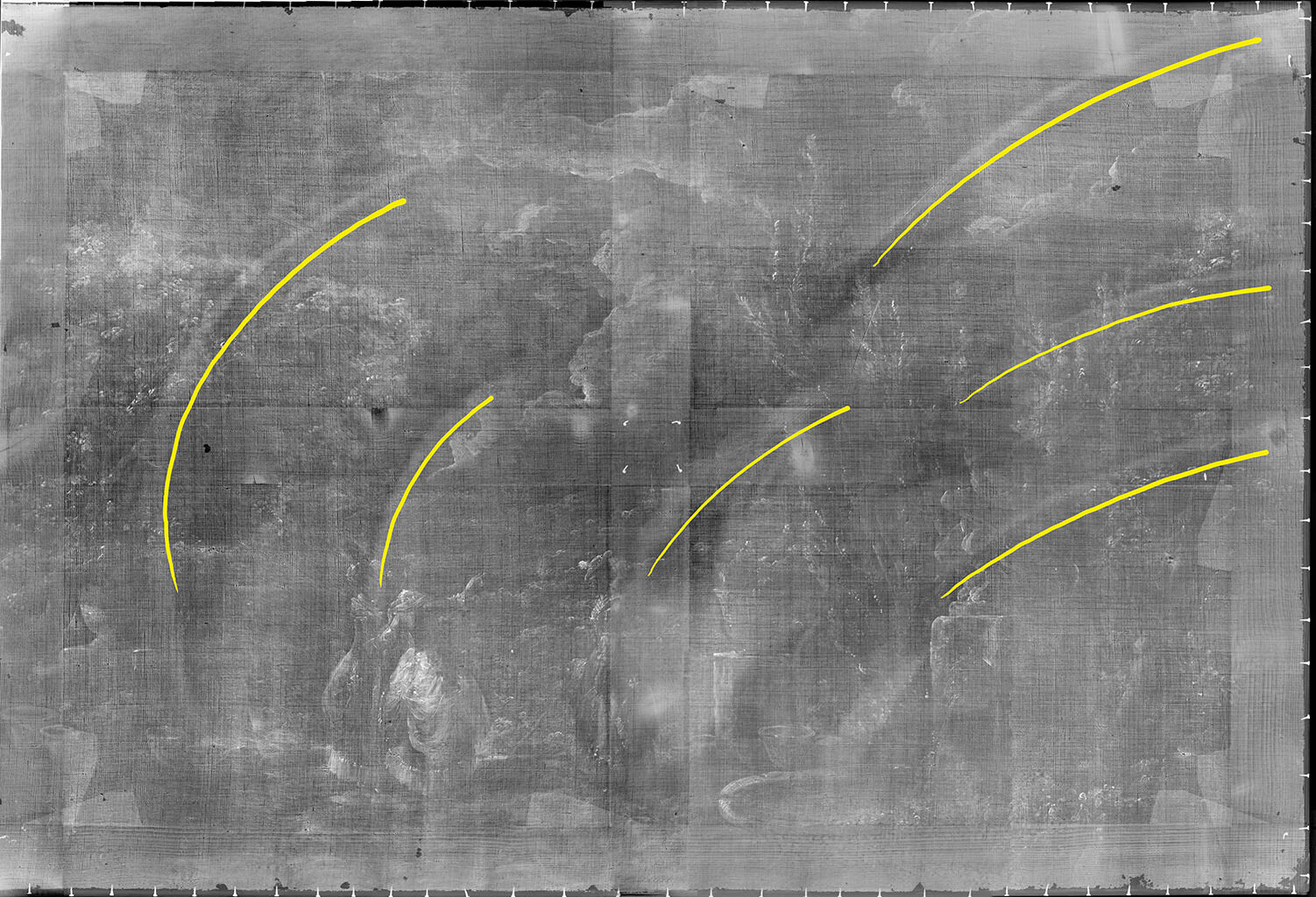

Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château was completed on a plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas with numerous irregularities and slubs. Prior to its acquisition in 1931, the painting was glue-paste linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive.,1A customs stamp on the reverse of the lining canvas indicates that the painting was lined before it arrived in the United States. and the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. were removed, limiting study of the original canvas. There is slight cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. along the upper, lower, and right edges, with less cusping along the left edge. Vertical crossbar cracksstretcher cracks: Linear cracks or deformations in the painting’s surface that correspond to the inner edges of the underlying stretcher or strainer members. are not centrally located, and their position (left of center) is more prominent using infrared reflectography (IRR)infrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. (Fig. 8). Taken together, these findings indicate that approximately seven centimeters were trimmed from the left side of the composition.

Fig. 8. Infrared reflectogram captured at 2050 nanometers, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80), revealing a detailed underdrawing and highlighting the off-center vertical crossbar cracks

Fig. 8. Infrared reflectogram captured at 2050 nanometers, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80), revealing a detailed underdrawing and highlighting the off-center vertical crossbar cracks

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of a crater from a metal soap in the sky, revealing the red and white ground layers, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph of a crater from a metal soap in the sky, revealing the red and white ground layers, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

The canvas was prepared with a double groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. consisting of a warm red layer beneath an upper whitish-gray layer.2For a discussion on double grounds, see Elma O’Donoghue, Rafael Romero, and Joris Dik, “French Eighteenth-Century Painting Techniques,” supplement, Studies in Conservation 43, no. S1 (1998): 185–89. The authors also specifically refer to a “fantasy landscape” by Hubert Robert in Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s collection. Both layers are visible through ruptured lead soap aggregates on the surface of the painting (Fig. 9).3For an explanation of metal soap formation in paintings, see Francesca Caterina Izzo, Matilde Kratter, Austin Nevin, and Elisabetta Zendri, “A Critical Review on the Analysis of Metal Soaps in Oil Paintings,” ChemistryOpen 10, no. 9 (September 2021): 904–21. The x-radiographX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. (Fig. 10) reveals dense, curving lines across the upper half of the canvas that are likely caused by the curved knife traditionally used to prime canvases.4See Maartje Witlox and Leslie Carlyle, “‘A Perfect Ground is the Very Soul of the Art’ (Kingston 1835): Ground Recipes for Oil Painting 1600–1900,” in ICOM 14th Triennial Meeting, The Hague, 12–16 September 2005 (London: James and James, 2005), 1:519–28. Several incised lines are also apparent, though it is unclear whether they are artifacts from the ground application or compositional planning.

Fig. 10. Composite digital radiograph of Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80), highlighting the varying thickness of ground application (yellow lines)

Fig. 10. Composite digital radiograph of Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80), highlighting the varying thickness of ground application (yellow lines)

Fig 11. Photomicrograph of the visible underdrawing in the center figure, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig 11. Photomicrograph of the visible underdrawing in the center figure, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 12. Infrared reflectogram captured at 2050 nanometers, showing changes in the underdrawing in the large urn on the right, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 12. Infrared reflectogram captured at 2050 nanometers, showing changes in the underdrawing in the large urn on the right, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

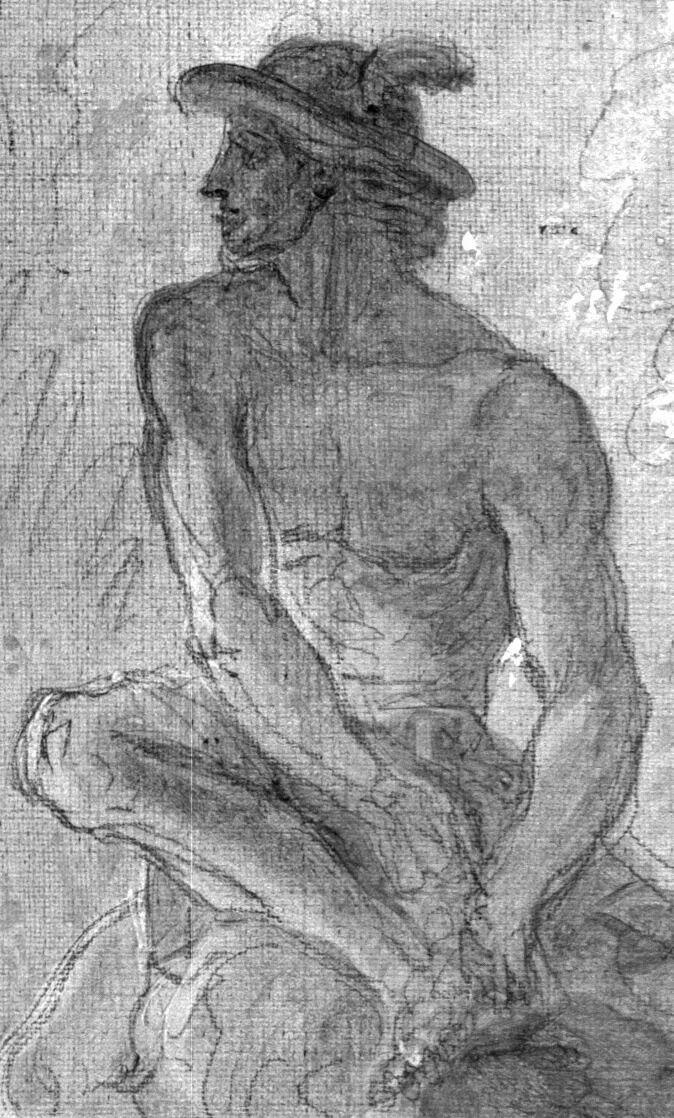

Some sketchy graphite lines are visible beneath thinly painted passages

in normal illumination (Fig. 11), but a comprehensive view of Robert’s

underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. was achieved using IRR (Fig. 8). Robert loosely represented

the foliage and horizon with gestural, looping, or undulating lines. The

figures, statue, and objects on the terrace are more fully described in

the underdrawing, establishing their place in the composition. Robert

developed and edited the composition as he was drawing, one example

being reshaping and adding feet to the urns (Fig. 12). In contrast to the

simple oval sketches outlining the three figures’ faces (Fig. 13), the

statue of Mercury has a detailed underdrawing, with a

defined profile and fully developed musculature (Fig. 14). Interestingly,

there is no underdrawing beneath the inscription on the statue’s base,

and although Robert often incorporated his signature and other data

(like the year or his patron) into his paintings as part of inscriptions

on architectural elements,5One such inscription can be found in Robert’s 1787 painting The Obelisk (The Art Institute of Chicago), https://www.artic.edu

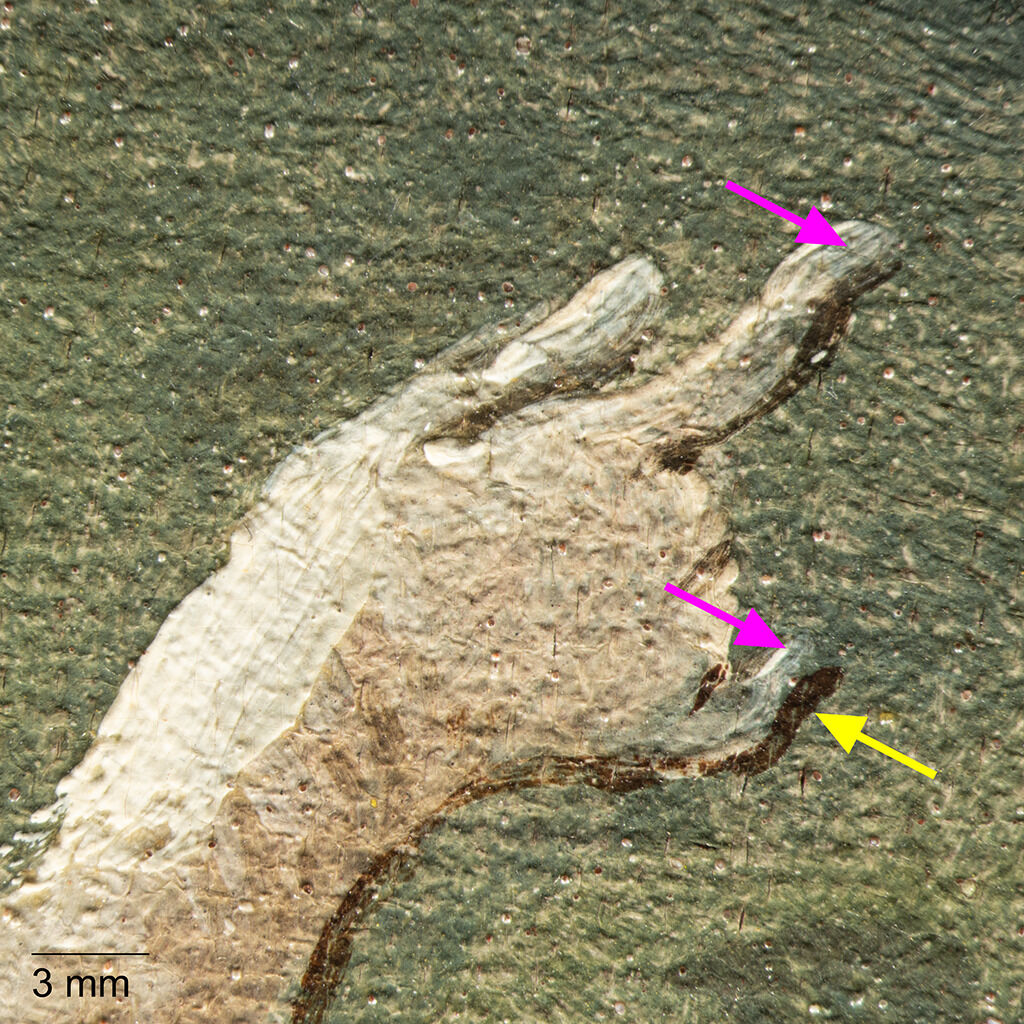

Fig. 13. Two detail images of the left figure’s head, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80). On the left, a normal illumination detail. On the right, an infrared reflectogram that reveals the simple oval underdrawing of the figure’s face. The figure’s hat was once much larger, as seen in the underdrawing (yellow arrow) and an earlier painted version (pink arrows).

Fig. 13. Two detail images of the left figure’s head, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80). On the left, a normal illumination detail. On the right, an infrared reflectogram that reveals the simple oval underdrawing of the figure’s face. The figure’s hat was once much larger, as seen in the underdrawing (yellow arrow) and an earlier painted version (pink arrows).

Fig. 14. Infrared reflectogram captured at 2050 nanometers, showing the statue’s highly detailed underdrawing, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 14. Infrared reflectogram captured at 2050 nanometers, showing the statue’s highly detailed underdrawing, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 15. Detail image of the inscription on the base of the statue, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 15. Detail image of the inscription on the base of the statue, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Following his underdrawing, Robert blocked in the composition with thin washeswash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent.—greens for foliage, pale blue in the sky, and brown tones for the statue and figures. Some of these initial washes remain visible, representing the midtones of the bodies of the large urns and the figures’ hair. Consistent with contemporaneous accounts of his process,6Charles Fournier des Ormes, a student of Robert, is quoted as saying the artist “worked with extraordinary facility; he would often complete a large painting in a single day.” Translated in Margaret Morgan Grasselli and Yuriko Jackall, Hubert Robert (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2016), 53. Robert’s close friend and fellow artist Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) said, “[H]e could paint a picture as fast as he could write a letter.” Cited and translated in Joseph Baillio, “Robert’s Decorations for the Chateau de Bagatelle,” in Metropolitan Museum Journal 27 (1992): 158. Robert appears to have almost exclusively painted wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. and wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color., executing the painting over a short period of time. He built up passages in thin layers, generally using painterly brushwork and minimal impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges.. The trees and foliage are defined with short, curving brushstrokes, stippling, and dabs of darker green for individual leaves. Trunks are laid in over the foliage using deep brown. Thicker, diagonal, blue brushstrokes in the sky provide a cool contrast to the robust pink clouds in the center and the thinly painted sky to the left, where the underlying red ground adds warmth. Concurrent painting of the sky and landscape resulted in spots of soft blending in the upper canopy of the left trees and along the horizon (Fig. 16).

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of soft blending along the upper canopy of trees, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of soft blending along the upper canopy of trees, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of the château in the background, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 17. Photomicrograph of the château in the background, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

The soft grays of the château (Fig. 17) are the result of Robert’s wet-into-wet application of pink paint, intentionally pulling it across the wet green beneath. The same intentional blending with lively brushwork and dragging of one color over another appears in the figures’ gowns. To add dimension to the statue of Mercury, Robert first built up shadow, following with brown and gray outlines to strengthen forms, then using thicker wet-over-wet brushstrokes and dabs for bright areas of highlight. Similar dark outlining also defines the shape of the figures’ gowns, hands, and faces (Fig. 18). In the immediate foreground, Robert developed the terrace with brushy application of tans, browns, peach, and yellow, allowing much of the ground or underpaintingunderpainting: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called ébauche. to remain visible. Zig-zagging strokes are clear in darker paint, and there is evidence of frenetic blending, especially at the interface of the greenery and the ground beneath the figures. In the final stages of painting, Robert added highlights and details like flowers using thick dabs of paint (Fig. 19).

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of the center figure’s hand, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80), showing dark brown outlining to strengthen forms (yellow arrow) and artist’s changes indicated by areas of green visible through the figure’s fingers (pink arrows)

Fig. 18. Photomicrograph of the center figure’s hand, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80), showing dark brown outlining to strengthen forms (yellow arrow) and artist’s changes indicated by areas of green visible through the figure’s fingers (pink arrows)

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph of flowers in the urn to the right, showing dabs of paint with slight impasto creating highlights, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

Fig. 19. Photomicrograph of flowers in the urn to the right, showing dabs of paint with slight impasto creating highlights, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château (ca. 1775–80)

As he painted, the artist continued making numerous adjustments to the composition. For example, underlying green from the background is visible through parts of the central figure’s extended hand (Fig. 18), indicating a slight shift to its shape and size. Robert originally positioned the right figure’s walking stick at a steeper angle, closer to her body. The figure’s proper right hand was first sketched lower than its current location, and a pentimentopentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind." hand appears above its final placement (Fig. 20).

Paint over the artist’s change in the hand does not visually match the color of the adjacent foliage; the same phenomenon occurs behind the right figure’s head and above the left figure’s hat. IRR shows that the left figure’s hat is much larger in the underdrawing, and underlying paint texture indicates that it was the same larger size in an earlier painted version (Fig. 13). To cover his sketching and reduce the size of the hat, Robert would have added green paint in this area, which likely contained different pigments than the green used for background foliage. Visually similar in color to start, the two paints aged differently over time and possibly became increasingly transparent.7For a discussion of increasing transparency in paint over time, see Andrea Kirsh and Rustin S. Levinson, Seeing Through Paintings: Physical Examination in Art Historical Studies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 161. Aged, discolored overpaintoverpaint: Restoration paint that covers original paint that may or may not be damaged. Historically, overpaint has often been applied too broadly, altering the intended aesthetic of the painting and sometimes introducing conceptions foreign to the original artist, thereby altering our understanding of the work and the era to which it belongs. may further complicate this area. Neither examination using ultraviolet (UV) radiationultraviolet (UV) radiation: A segment of the electromagnetic spectrum, just beyond the sensitivity of the human eye, with wavelengths ranging from 100–400 nanometers. For a description of its use in the study of art objects, see ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence. nor magnification was conclusive. Modern retouching is typically identifiable by its non-fluorescence, appearing dark in UV (Fig. 21). Older retouching can be difficult to differentiate from original paint, as its UV-induced visible fluorescenceultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. can appear similar, which is the case here. Examination under magnification was hampered by the presence of later retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. obscuring the layering structure. A definitive conclusion would require instrumental analysis or destructive sampling.

The painting is in good condition. There is craquelurecraquelure: The network or pattern of cracks that develop on a paint surface as it ages. throughout the sky and mechanical crackingmechanical cracks: Cracks, either localized or overall, that form in response to movement or stress. at both upper corners associated with the tensioning of the canvas. The past lining caused an overall enhancement of the weave textureweave interference: A distortion that can occur when excess heat or pressure is applied to a painting, usually during the lining process. As a result, the original canvas weave texture becomes more pronounced or the weave texture of the lining material becomes visible on the painting surface. Also called weave emphasis or weave accentuation., several small bulges in the canvas, and a raised line running horizontally though the painting. Widespread paint abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. is likely the result of a harsh cleaning during a past treatment, and these abraded areas were reintegrated in a 1946 treatment by Nelson-Atkins conservator James Roth.8James Roth, treatment report, December 1946, NAMA conservation file, no. 31-97. A label on the stretcher indicates that Marcel-Jules Rougeron treated the painting. Rougeron (1875–1954) was a paintings restorer, art dealer, and collector in New York. For more on Roth and conservation at the Nelson-Atkins, see Seth Adam Hindin, “How the West Was Won: Charles Muskavitch, James Roth, and the Arrival of ‘Scientific’ Art Conservation in the Western United States,” Journal of Art Historiography, no. 11 (December 2014): https://arthistoriography.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/hindin.pdf. There are no records of subsequent treatment, but NAMA conservation files are incomplete prior to 1973. Small spots of Roth’s retouching are most prevalent in the sky. There are few larger passages of retouching, although a diagonal passage 5 centimeters in length cuts across the base of the statue, and there is evidence of one or more campaigns of retouching in the faces of the right and left figures (Fig. 21). The painting has a surface coating of dammar varnish and an additional synthetic varnish layer; both varnishes have likely discolored.9Mary Schafer, technical notes, April 12, 2011, NAMA conservation file, no. 31-97. The presence of a synthetic varnish was confirmed through solvent tests.

Notes

-

A customs stamp on the reverse of the lining canvas indicates that the painting was lined before it arrived in the United States.

-

For a discussion on double grounds, see Elma O’Donoghue, Rafael Romero, and Joris Dik, “French Eighteenth-Century Painting Techniques,” supplement, Studies in Conservation 43, no. S1 (1998): 185–89. The authors also specifically refer to a “fantasy landscape” by Hubert Robert in Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s collection.

-

For an explanation of metal soap formation in paintings, see Francesca Caterina Izzo, Matilde Kratter, Austin Nevin, and Elisabetta Zendri, “A Critical Review on the Analysis of Metal Soaps in Oil Paintings,” ChemistryOpen 10, no. 9 (September 2021): 904–21.

-

See Maartje Witlox and Leslie Carlyle, “‘A Perfect Ground is the Very Soul of the Art’ (Kingston 1835): Ground Recipes for Oil Painting 1600–1900,” in ICOM 14th Triennial Meeting, The Hague, 12–16 September 2005 (London: James and James, 2005), 1:519–28.

-

One such inscription can be found in Robert’s 1787 painting The Obelisk (The Art Institute of Chicago), https://www.artic.edu

/artworks ./57049 /the-obelisk -

Charles Fournier des Ormes, a student of Robert, is quoted as saying the artist “worked with extraordinary facility; he would often complete a large painting in a single day.” Translated in Margaret Morgan Grasselli and Yuriko Jackall, Hubert Robert (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2016), 53. Robert’s close friend and fellow artist Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842) said, “[H]e could paint a picture as fast as he could write a letter.” Cited and translated in Joseph Baillio, “Robert’s Decorations for the Chateau de Bagatelle,” in Metropolitan Museum Journal 27 (1992): 158.

-

For a discussion of increasing transparency in paint over time, see Andrea Kirsh and Rustin S. Levinson, Seeing Through Paintings: Physical Examination in Art Historical Studies (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 161.

-

James Roth, treatment report, December 1946, NAMA conservation file, no. 31-97. A label on the stretcher indicates that Marcel-Jules Rougeron treated the painting. Rougeron (1875–1954) was a paintings restorer, art dealer, and collector in New York. For more on Roth and conservation at the Nelson-Atkins, see Seth Adam Hindin, “How the West Was Won: Charles Muskavitch, James Roth, and the Arrival of ‘Scientific’ Art Conservation in the Western United States,” Journal of Art Historiography, no. 11 (December 2014): https://arthistoriography.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/hindin.pdf. There are no records of subsequent treatment, but NAMA conservation files are incomplete prior to 1973.

-

Mary Schafer, technical notes, April 12, 2011, NAMA conservation file, no. 31-97. The presence of a synthetic varnish was confirmed through solvent tests.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

Possibly Baron Gustave Samuel James de Rothschild (1829–1911), Paris, by May 25, 1892 [1];

Possibly given to his daughter, Berthe Juliette Gudule Leonino (née de Rothschild, 1870–1896), Paris, May 25, 1892–December 14, 1896 [2];

Baron Emmanuel David Berénd Leonino (1864–1936), Paris, by June 1928–July 24, 1931 [3];

Purchased from Leonino by Charles Michel, Paris, by July 24, 1931;

Purchased from Charles Michel, through Richard Owen and Harold Woodbury Parsons, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1931 [4].

Notes

[1] According to dealer Richard Owen, April 25, 1932, “The picture formerly was in the collection of the Baron Gustav [sic] de Rothschild of Paris, and on his death passed into the hands of Baron Leonino, his son-in-law, from whom it was purchased.” See letter from Owen to Paul Gardner, NAMA, April 25, 1932, NAMA curatorial files. However, Baron de Rothschild’s posthumous inventory from 1912 does not include any definitive indication of the Nelson-Atkins painting. There was one painting, no. 756, by the French eighteenth-century school, entitled Personnages dans un parc (Figures in a Park), that might correspond to The Nelson-Atkins painting, but it was not noted as being given to Baron Leonino. Sixty other paintings from Baron de Rothschild’s collection were given to Baron Leonino, but none of them correspond to the Nelson-Atkins painting. See “Inventaire après le décès de Monsieur le Baron Gustave de Rothschild,” April 26, 1912, 000/1037/122, and 000/929/38 (OE/346), The Rothschild Archive, London.

[2] It is possible that Baron de Rothschild’s daughter, Juliette Leonino (née de Rothschild), and her husband, Baron Leonino, already owned the Nelson-Atkins painting before the time of Baron de Rothschild’s posthumous inventory in 1912. In fact, a manuscript note in the Nelson-Atkins files says that Baron de Rothschild gave the painting as a wedding present to Juliette on May 25, 1892. See manuscript note, ca. 1934, NAMA curatorial files.

MacKenzie Mallon, provenance specialist, and Glynnis Stevenson, project assistant, NAMA, researched at the Rothschild Archive, London, and there is nothing definitive placing this painting in the collection of Gustave de Rothschild nor Juliette Leonino.

[3] Although Baron Leonino may have inherited the painting when his wife died in 1896, he was a collector too and may have purchased the painting himself. He definitely had the painting by June 1928 when he lent it to the La Saison de Bagatelle exhibition.

[4] See letter from Harold Woodbury Parsons to Herbert V. Jones, NAMA, February 15, 1932, NAMA curatorial files. Edward Morton is also erroneously given as the seller of the painting in several of the Nelson-Atkins documents, but he was the secretary to dealer Richard Owen, London.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Mercury Fastening His Sandal, 1744, marble, 22 13/16 x 14 x 13 in. (58 x 35.5 x 33 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, no. MR 1957.

Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Mercury Fastening His Sandal, 1748, marble, 76 3/4 x 47 1/4 x 37 13/16 in. (195 x 120 x 96 cm), Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst, Bode-Museum, Berlin, no. 356.

Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Mercury Fastening His Sandal, 1753, lead, 73 5/8 x 42 1/2 x 41 3/4 in. (187.1 x 108 x 106 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 3023.

Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, Mercury Fastening His Sandal, cast 1753, bronze, 73 5/8 x 42 1/2 x 41 3/4 in. (187.1 x 108 x 106 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, no. RF 3023.

Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of the Tivoli Waterfall, 1779, oil on canvas, 97 5/8 x 148 13/16 in. (248 x 378 cm), Château de Maisons, Maisons-Laffitte, acc. no. MAI 1989000058.

Hubert Robert, Ruins on the Terrace in Marly Park, early 1780s, oil on canvas, 23 3/16 x 34 1/4 in. (59 x 87 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

Hubert Robert, Two Statues in a Park, 1765–70, red chalk drawing on fine cream laid paper, 11 7/16 x 14 1/2 in. (29 x 36.8 cm), Musée des Beaux-Arts, Quimper, 873-2-40.

Hubert Robert, Terrace of an Italian Villa, ca. 1765, watercolor, brown ink, and red chalk counterproof on laid paper, 13 15/16 x 11 7/16 in. (35.5 x 29 cm), National Museum, Warsaw, acc. no. Rys.Ob.d.556 MNW.

Hubert Robert, Young Woman Holding a Basket, Descending Steps Near a Fountain, 1773, red chalk on paper, 14 5/16 x 11 in. (36.4 x 27.9 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. RF 28984, recto

Hubert Robert, Figures in a Park Bordered by an Overhanging Balustrade, ca. 1775, black crayon on laid paper, 4 3/5 x 3 1/2 in. (11.6 x 8.8 cm), Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Arts graphiques, RF 11567, recto.

Hubert Robert, Study for “Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château,” ca. 1775–80, black chalk, 6 5/8 x 8 5/8 in. (16.8 x 21.9 cm), The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 55-81.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

La Saison de Bagatelle: Exposition des Peintres de Jardins des XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles, Château de Bagatelle, Paris, June–July 1928, no. 79, as Vue prise de Marly vers Saint Germain-en-Laye.

Exposition de l’Art des Jardins et des Peintres de la Fleur, Musée des Beaux-Arts Jules Chéret, Nice, March–April 1929, no. 201, as Vue prise de Marly vers Saint Germain-en-laye.

Exhibition, Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, MO, April 11–May 20, 1932.

Loan Exhibition of Prints, Drawings, and Paintings Illustrating the Development of the Fountain, Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, April 4–27, 1935, no. 46, as The Terrace at Marly.

French Painting and Sculpture of the XVIII Century, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, November 6, 1935–January 5, 1936, no. 53, as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

French Painting, 1100–1900, Carnegie Institute, Pittsburgh, October 18–December 2, 1951, no. 91, as Terrace of Château de Marly.

French Eighteenth Century Painters: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Education Program of The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, October 6–November 2, 1954; Wildenstein, New York, November 16–December 11, 1954, no. 24, as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

Great French Paintings: An Exhibition in Memory of Chauncey McCormick, The Art Institute of Chicago, January 20–February 20, 1955, no. 36, as Terrace at the Château de Marly.

The Century of Mozart, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 15–March 4, 1956, no. 94, as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

Homage to Mozart: A Loan Exhibition of European Painting, 1750–1800, Honoring the 200th Anniversary of Mozart’s Birth, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT, March 22–April 29, 1956, no. 52, as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

Fontinalia: The Art of the Fountain and the Fountain in Art: A Loan Exhibition of Sculpture, Paintings, Drawings, Prints, and Photographs, The University of Kansas Museum of Art, Spooner Hall, Lawrence, KS, October 19–November 30, 1957, no. 45, as The Terrace at Marly.

The French Tradition, Marion Koogler McNay Art Institute, San Antonio, TX, February 8–March 12, 1961, no cat., as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

Hubert Robert, 1733–1808: Paintings and Drawings, Vassar College Art Gallery, Poughkeepsie, NY, October 9–November 11, 1962, no. 15, as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

The Romantic Era: Birth and Flowering, 1750–1850, Art Association of Indianapolis, Herron Museum of Art, February 21–April 11, 1965, no. 5, as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

The Eye of Thomas Jefferson, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, June 5–September 6, 1976, no. 208, as The Terrace of the Château at Marly.

Hubert Robert: The Pleasure of Ruins, Wildenstein, New York, November 15–December 16, 1988, unnumbered, as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

Hubert Robert, Musée du Louvre, Paris, March 9–May 30, 2016; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, June 26–October 2, 2016, no. 70 (Washington, DC, only), as The Terrace at the Château de Marly.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Hubert Robert, Imaginary View of Three Women Contemplating a Château, ca. 1775–80,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.330.4033.

Possibly Joshua James Foster, French Art from Watteau to Prud’hon (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1907), 3:65, as Vue de Marly.

La Saison de Bagatelle: Exposition des Peintres de Jardins des XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles, exh. cat. (Paris: Frazier-Soye, 1928), 16, (repro.), as Vue prise de Marly vers Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Xavier d’Orfeuil, “La Vie qui passe: Les Peintres de jardins à Bagatelle,” Le Gaulois, no. 18516 (June 16, 1928): 1, as Vue prise de Marly vers Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

May Birkhead, “Paris Exhibits Art of Watteau Period: Works of Eighteenth Century Painters Shown In Setting of Bagatelle Garden,” New York Times 77, no. 25,726 (July 1, 1928): E[1].

René Barotte, “Les grandes expositions: Au Château de Bagatelle,” L’Homme libre, no. 4383 (July 23, 1928): 2, as Les jardins de Marly.

H. Marcel Magne, “L’Art des Jardins a [sic] Bagatelle,” La Renaissance de l’art français et des industries de luxe, no. 8 (August 1928): 356.

Raymond Bouyer, “Revue de l’Exposition au Bagatelle,” Bulletin de l’Art ancien et moderne, no. 751 (September–October 1928): 305, (repro.), as Vue prise d’un jardin de Marly.

Exposition de l’Art des Jardins et des Peintres de la Fleur, exh. cat. (Nice: Musée des beaux-arts Jules Chéret, 1929), 38, (repro.), as Vue prise de Marly vers Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

Georges Avril, “L’Exposition de l’art des jardins au musée Jules Chéret,” L’Éclaireur du dimanche et “La Vie pratique, Courrier des étrangers,” no. 404 (March 31, 1929): 21, (repro.), as Vue prise de Marly vers Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

“Musée Jules Chéret a [sic] Nice: L’art des Jardins,” Bulletin des musées de France, no. 7 (July 1929): 159, as la vue de Marly.

Paul Sentenac, Hubert Robert (Paris: Les Éditions Rieder, 1929), 52, 63n44, (repro.), as Vue de Saint-Germain prise d’une terrasse de Marly.

“The Nelson Collection Grows,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 120 (January 15, 1932): D.

“Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post 78, no. 224 (January 17, 1932): 2-C, erroneously as Terrace at St. Germain.

“View New Nelson Art: Purchases for Gallery Inspected by Institute Trustees,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 122 (January 17, 1932): 3, 8A, (repro.).

“Kansas City Museum Acquires Nine More Works from Nelson Fund,” Art Digest 6, no. 9 (February 1, 1932): 7, (repro.), as Three Ladies on the Terrace at Marly.

“Additional Old Masters Secured for Kansas City,” Art News 30, no. 19 (February 6, 1932): 1, as The Terrace of Chateau de Marly.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Mr. Parsons Will Be Heard Thursday Night on ‘The Italian Renaissance,’” Kansas City Times 95, no. 88 (April 12, 1932): 10.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Art Paid Its Chief Homage to Beautiful Women in Eighteenth-Century France, Paul Gardner Tells Audience in Epperson Hall,” Kansas City Times 93, no. 119 (May 18, 1932): 11.

Georges Isarlov, La Peinture Française à l’Exposition de Londres 1932 (Paris: José Corti, 1932), 26.

Edmond Pilon, “Le Bi-Centenaire du peintre Hubert Robert (1733–1808),” Le Correspondant 331 (May 25, 1933): 523, as Vue de Saint-Germain prise d’une terrasse de Marly.

André Delacour, “À travers les revues: L’esprit de la peinture: Le bi-centenaire de Hubert-Robert,” L’Européen, no. 214 (June 2, 1933): 4, as Vue de Saint-Germain prise d’une terrasse de Marly.

“American Art Notes: New Nelson Gallery of Art,” Connoisseur 92, no. 388 (December 1933): 419.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 13, 20, 22, (repro.), as Terrace of the Chateau of Marly and Three Ladies on Terrace of Chateau de Marly.

Pierre Domène, “Le nouveau musée de Kansas City,” Beaux-Arts 72, no. 48 (December 1, 1933): 2.

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, 30, as Terrace of Chateau de Marly.

Minna K. Powell, “The First Exhibition of the Great Art Treasures: Paintings and Sculpture, Tapestries and Panels, Period Rooms and Beautiful Galleries Are Revealed in the Collections Now Housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 84 (December 10, 1933): 4C, as The Terrace of the Chateau of Marly.

Luigi Vaiani, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand: Critic Views Wide Collection of Beauty as Public Prepares to Pay its First Visit to Museum,” Kansas City Journal-Post 80, no. 187 (December 11, 1933): 7.

“Praises the Gallery: Dr. Nelson M’Cleary, Noted Artist, a Visitor,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 98 (December 24, 1933): 9A, as Terrace of the Chateau of Marly.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 41, 46, (repro.), as Terrace of Chateau of Marly.

“Museums, Art Associations and Other Organizations,” in “For the Year 1933,” American Art Annual 30 (1934): 175, as Chateau Marly.

George Isarlov, “Notes d’Art: L’Exposition Hubert-Robert,” La Concorde (January 5, 1934).

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16, as Chateau Terrace.

“A Thrill to Art Expert: M. Jamot is Generous in his Praise of Nelson Gallery; Early French Section in Particular Is Pleasing to the Curator of Paintings at the Louvre,” Kansas City Times 97, no. 247 (October 15, 1934): 7.

Bertha H[arris] Wiles, Loan Exhibition of Prints, Drawings, and Paintings Illustrating the Development of the Fountain, exh. cat. (Boston: Fogg Art Museum, 1935), unpaginated, as The Terrace at Marly.

French Painting and Sculpture of the XVIII Century, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1935), 10, (repro.), as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

News Flashes (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 2, no. 4 (January 1–16, 1936): 3.

Jean Morgan, “La Double Erreur: Dernière Partie,” Revue Des Deux Mondes 40, no. 3 (August 1, 1937): 650.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 41, 47, 168, (repro.), as Terrace of the Chateau of Marly.

Dorothy Adlow, “Terrace of the Chateau of Marly: A Painting by Hubert Robert,” Christian Science Monitor 34, no. 71 (February 17, 1942): 12, (repro.), as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

Jeanne and Alfred Marie, Marly (Paris: Editions Tel, 1947), 19.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 61, (repro.), as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

French Painting, 1100–1900, exh. cat. (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute, 1951), (repro.), as Terrace of Château de Marly.

French Eighteenth Century Painters: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Education Program of The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1954), unpaginated, as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

Pierre Rossillion, “Art et urbanisme: Les forêts de l’Ile-de-France,” Le Jardin des Arts 1, no. 12 (October 1955): 705, (repro.), as Vue de Marly sur Saint Germain.

Winifred Shields, “Sketch of French Landscape Acquired by Nelson Gallery: Drawing Purchased from a Dealer is a Preliminary Study for the ‘Terrace of the Chateau [sic] of Marly,’ a Painting Long in the Collection Here,” Kansas City Star 75, no. 329 (August 12, 1955): 14, (repro.), as Terrace of the Chateau of Marly.

Great French Paintings: An Exhibition in Memory of Chauncey McCormick, exh. cat. (Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 1955), unpaginated, as Terrace at the Château de Marly.

“The Century of Mozart: January 15 through March 4, 1956,” exh. cat., Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 1, no. 1 (January 1956): 13, 31, as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

“Special Exhibition: The Century of Mozart,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 23, no. 5 (February 1956): unpaginated, as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

Homage to Mozart: A Loan Exhibition of European Painting, 1750–1800, Honoring the 200th Anniversary of Mozart’s Birth, exh. cat. (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1956), 21, as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

Fontinalia: The Art of the Fountain and the Fountain in Art; A Loan Exhibition of Sculpture, Paintings, Drawings, Prints, and Photographs, exh. cat. (Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Museum of Art, 1957), 25, as The Terrace at Marly.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 113, 261, (repro.), as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

Thomas J. McCormick, Hubert Robert, 1733–1808: Paintings and Drawings, exh. cat. (Poughkeepsie, NY: Vassar College Art Gallery, 1962), unpaginated, as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

Clare Le Corbeiller, “Mercury, Messenger of Taste,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 22, no. 1 (Summer 1963): 26–27, (repro.), as The Terrace of the Château de Marly.

“Gallic Fete at Gallery,” newspaper unknown (ca. November 1964), (repro.), clipping, scrapbook, NAMA Archives, vol. 20, p. 83.

The Romantic Era: Birth and Flowering, 1750–1850, exh. cat. (Indianapolis: Art Association of Indianapolis, Herron Museum of Art, 1965), (repro.), as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

W. G. Constable, “‘The Romantic Era’ Exhibition,” Connoisseur 158, no. 638 (April 1965): 257, (repro.), as The Terrace at the Château de Marly.

Ralph T. Coe, “The Baroque and Rococo in France and Italy,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 537–39, (repro.) [repr. in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 69–71, (repro.)], as Terrace of Château de Marly.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 137, 258, (repro.), as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

The Elegant Academics: Chroniclers of Nineteenth-Century Parisian Life, exh. cat. (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1974), 21, as The Terrace of the Château de Marly.

William Howard Adams, ed., The Eye of Thomas Jefferson, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1976), 132, 368, (repro.), as The Terrace of the Château at Marly.

Joseph A. Lastelic, “Jefferson Exhibit Probes Remarkable Mind,” Kansas City Times 108, no. 229 (May 31, 1976): 18C, as Terrace of the Chateau de Marly.

Jean-René Gaborit, Jean-Baptiste Pigalle, 1714–1785: Sculptures du Musée du Louvre (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1985), 44–45, (repro.), as Terrasse du château de Marly.

Collection de Monsieur et Madame Roberto Polo: Vingt-six Chefs-d’Œuvre de la Peinture Française du XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Ader Picard Tajan, May 30, 1988), 50, as Terrasse du Château de Marly.

Hubert Robert: The Pleasure of Ruins, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1988), 46, 87, (repro.), as Terrace of the Château de Marly.

Joseph Baillio, “Hubert Robert’s Decorations for the Chateau de Bagatelle,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 27 (1992): 164–65, 181n28, (repro.), as The Terrace of the Château de Marly.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 195, (repro.), as The Terrace of the Château de Marly.

William Howard Adams, The Paris Years of Thomas Jefferson (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997), 240, (repro.), as The Terrace of the Château at Marly.

Arts of France: Important French Furniture, Paintings, Sculpture, Silver, Porcelain, and Tapestries (New York: Christie, Manson and Woods, October 23, 1998), 189, as The Terrace of the Château at Marly.