Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Kristel Smentek, “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.322.5407.

MLA:

Smentek, Kristel. “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.322.5407.

In this painting by Jean Etienne Liotard, a sumptuously clothed woman, wearing the layered garments typical of Ottoman Turkish women’s dress, gestures to her more modestly attired attendant. Every detail of clothing is carefully and accurately rendered in thin, smooth layers of paint, from the sheen of the servant’s striped silk habit to the details of her mistress’s embroidered red robe, loose trousers, and scarves, and the reflected light on her gold coin necklace, filigree bracelet, and delicate rings. The basin (kurna) in the background indicates that the women are in the public bath (hamam), as do the high pattens or clogs (nalin) that both wear to protect their feet from the damp floor. The double-sided comb and pot of henna on the servant’s tray additionally reference the rituals of the bath.

Both the rigorously descriptive technique and the subject of the painting are characteristic of Liotard’s work. Born in Geneva in 1702, Liotard was one of eighteenth-century Europe’s most eclectic artists. After training as a miniaturist in Geneva and in Paris, Liotard set sail in 1738 for the Ottoman Empire in the company of Sir William Ponsonby (1704–93), the future Earl of Bessborough, a British aristocrat embarking on his Grand TourGrand Tour: An extended tour of Europe, in particular Italy, in the eighteenth century, taken by wealthy young men (and some women), especially British and American ones, to complete their education and cultivation.. Ponsonby remained Liotard’s most dedicated patron for his entire career and served as his connection to other British peers. Liotard stayed in the Eastern Mediterranean until 1742, working first in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) and later at the court of the Ottoman vassal state of Moldavia (present-day Romania and Moldova). His sojourn in the Ottoman Empire and his firsthand encounters with its peoples were aspects of the persona of le peintre turc (the Turkish painter) that he fashioned for himself once he returned to Europe in 1743. Although Liotard resided in the capitals of western Europe for the rest of his life, he continued to wear the vaguely Turkish costume of a robe, cap, and baggy pants that he first adopted in Constantinople until his death in 1789 (Fig. 1). A prolific and incisive portraitist in pastel, enamel, and oils, Liotard forged an immensely successful practice for himself, working in Vienna, Paris, London, Amsterdam, Geneva, and elsewhere. Throughout his long career, Liotard continued to create and exhibit Turkish-themed drawings and pastels.1For a discussion of Liotard’s Ottoman drawings, see Anne de Herdt, Dessins de Liotard: Suivi du catalogue de l’œuvre dessiné (Geneva: Musée d’art et d’histoire, 1992), nos. 9–74, pp. 38–147; and Marcel Roethlisberger and Renée Loche, Liotard: Catalogue, Sources et Correspondance (Doornspijk, Netherlands: Davaco, 2008), 1:159–61. Such pictures simultaneously consolidated his reputation as le peintre turc and catered to widespread European interest in the Ottoman Empire and its inhabitants.

Nevertheless, like all his Turkish-themed pictures, Liotard’s painting of the women in the hamam is staged. Although they are dressed in Turkish clothing, the women are not Turkish Muslims but Franks, a catchall term used to describe Europeans living in the Ottoman Empire. As a European man, Liotard had no access to Muslim women, nor did he or any man, Frankish or Muslim, have access to the bath when women were present. Liotard’s painting thus presents the viewer with a fictional glimpse into the unseen lives of women in the empire. Like the equally inaccessible harem, the women’s bath had long been a subject of European fascination.2Leslie Leubbers, “Documenting the Invisible: European Images of Ottoman Women, 1567–1867,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter 24, no. 1 (March–April 1993): 1–7.

The painting purchased by Monckton-Arundell in 1787 reappears in the historical record in 1924. In a letter dated February 22, 1924, Robert Langton Douglas (1864–1951), an art critic, prominent dealer, and the director of the National Gallery of Ireland, wrote to thank George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscount Galway, for allowing him to visit his estate, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, York, and see his “paintings by Liotard and Pannini [sic].”14Letter from Douglas to George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, February 22, 1924, Correspondence and Personal Papers of George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscount Galway (1844–1931), and Vere Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscountess Galway (d. 1931), Manuscripts and Special Collections, Ga 2 E 180, University of Nottingham Libraries. The Liotard that Douglas mentions might have been the Nelson-Atkins painting. This would suggest that it passed by law of succession through the Monckton-Arundell family. In 1947, the painting, perhaps erroneously listed as “A Coloured Pastel” and titled Interior with Turkish Lady and Servant in Richly Coloured Robes, was sold by Lucia Emily Margaret Monckton-Arundell (née White, 1890–1983), 8th Viscountess Galway, in what appears to have been a large estate sale from her family home.15Oil Paintings and Water Colours by Old Masters; . . . By order of the Rt. Hon. the Viscountess Galway (Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK: Henry Spencer and Sons, 1947), 17, erroneously as A Coloured Pastel—Interior with Turkish Lady and Servant in richly coloured robes. This narrative does not correspond to any of the other four known versions of the painting, as each of them were accounted for in other collections in 1947.16The Geneva and Wintherthur versions have remained in Switzerland since the 1930s. The Qatar version was in London in 1935, and then it was with Alfred Hausammann in Zurich until it descended to his daughter in 1978. The version once possessed by John Hawkins was purchased from Geneva dealer Rodolphe Dunki by Bernard Naef, Geneva, in 1937, and remained with his descendants until 1995. Marcel Rœthlisberger, Liotard’s cataloguer, attests that it is highly unlikely that there is a sixth, undiscovered pastel version of this motif.17See email from Marcel Rœthlisberger, professor emeritus, University of Geneva, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, May 16, 2018, NAMA curatorial files. Instead, he agrees that the “Coloured Pastel” in the 1947 sale is probably the Nelson-Atkins oil painting. It was very common for Liotard’s works to be identified as pastels because the artist worked far more frequently in that medium than he did in oil. This makes it likely that the Nelson-Atkins picture belonged to the Monckton-Arundell family for most of its history. Furthermore, this fits with what we know of Liotard’s popularity among British collectors and suggests that for some of Liotard’s admirers, the artist’s Turkish genre scenes functioned as much to underscore their self-representation as men who had traveled to the empire as they did for le peintre turc himself.

Notes

-

For a discussion of Liotard’s Ottoman drawings, see Anne de Herdt, Dessins de Liotard: Suivi du catalogue de l’œuvre dessiné (Geneva: Musée d’art et d’histoire, 1992), nos. 9–74, pp. 38–147; and Marcel Roethlisberger and Renée Loche, Liotard: Catalogue, Sources et Correspondance (Doornspijk, Netherlands: Davaco, 2008), 1:159–61.

-

Leslie Leubbers, “Documenting the Invisible: European Images of Ottoman Women, 1567–1867,” The Print Collector’s Newsletter 24, no. 1 (March–April 1993): 1–7.

-

Figure 2 in this catalogue entry is courtesy of the New York Public Library https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-69f9-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99. See other examples in Günsel Renda, “The Ottoman Bath Through the Painter’s Eye,” in Bathing Culture of Anatolian Civilizations: Architecture, History and Imagination, ed. Nina Ergin (Leuven: Peeters, 2011), pp. 305–29, esp. figs. 12–24; and Bronwen Wilson, “Foggie diverse di vestire de’ Turchi: Turkish Costume Illustration and Cultural Translation,” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 37, no. 1 (Winter 2007): pp. 97–139, esp. pp. 112–15, and fig. 12.

-

Roethlisberger and Loche, Liotard, nos. 67, 69, and 297, pp. 1:275–76, 464.

-

Roethlisberger and Loche, Liotard, no. 298, p. 1:464.

-

Roethlisberger and Loche, Liotard, 1:275.

-

Mary Schafer, Technical Notes, August 15, 2011, NAMA conservation files, 56-3.

-

See Andreas Holleczek’s essay in Thomas W. Gaehtgens and Christian Michel, eds., L’art et les normes sociales au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: Éditions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, 2001).

-

See A Catalogue of the late Sir Everard Fawkener’s Pictures, . . . Several large portraits of English Gentlemen, by Liotard, in frames and glasses . . . (London, 1759), lot 57, as “A Turkish lady and her slave small whole lengths in a Frame and glass.” The presence of glass suggests the work was a pastel. The works by Liotard in the Fawkener sale are transcribed in Roethlisberger and Loche, Liotard, 1:161. They note that Fawkener’s Turkish-themed works by Liotard were probably executed in Constantinople.

-

Roethlisberger and Loche, Liotard, no. 297, p. 1:464; De Herdt, Dessins, no. 29, pp. 70–71.

-

I thank Glynnis Napier Stevenson for the provenance of this painting, the information about the Monckton-Arundell and Westenra families, and the revisions to this entry. See A Catalogue of the Elegant Household Furniture, Collection of Pictures, . . . The Property of A Lady of Fashion, at her house, Situate no. 48, on the South Side of Charles Street, Berkeley Square (London: Christie’s, February 5–6, 1787), 12, as A Turkish lady and her Servant.

-

In the sales ledger, he was listed as “L Galway,” and the name “Monckton” appears repeatedly throughout the ledger.

-

Land tax records for Charles Street from 1786 to 1787 show that “Lady Galway” owned property there. Lady Galway lived there with her daughter, Miss Mary Monckton (1748–1840), who operated a renowned salon at the Charles Street property and was a well-known “lady of fashion”; see Amy Prendergast, Literary Salons Across Britain and Ireland in the Long Eighteenth Century (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015), 61. However, the year before the painting was sold, Mary Monckton married Edmund Boyle (1742–98), 7th Earl of Cork and 7th Earl of Orrery, and moved to his home in New Burlington Street, London.

-

Letter from Douglas to George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, February 22, 1924, Correspondence and Personal Papers of George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscount Galway (1844–1931), and Vere Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscountess Galway (d. 1931), Manuscripts and Special Collections, Ga 2 E 180, University of Nottingham Libraries.

-

Oil Paintings and Water Colours by Old Masters; . . . By order of the Rt. Hon. the Viscountess Galway (Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK: Henry Spencer and Sons, 1947), 17, erroneously as A Coloured Pastel—Interior with Turkish Lady and Servant in richly coloured robes.

-

The Geneva and Wintherthur versions have remained in Switzerland since the 1930s. The Qatar version was in London in 1935, and then it was with Alfred Hausammann in Zurich until it descended to his daughter in 1978. The version once possessed by John Hawkins was purchased from Geneva dealer Rodolphe Dunki by Bernard Naef, Geneva, in 1937, and remained with his descendants until 1995.

-

See email from Marcel Rœthlisberger, professor emeritus, University of Geneva, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, May 16, 2018, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Diana M. Jaskierny, “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.322.2088.

MLA:

Jaskierny, Diana M. “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.322.2088.

A Lady in Turkish Dress and her Servant by Jean Etienne Liotard (1702–89) exemplifies the artist’s abilities as a miniaturist and pastel painter, with a combination of detailed and diffused passages. Executed on a plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas, the painting appears to retain its original dimensions, despite the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. no longer being extant. Near the bottom edge, a linear bead of paint indicates where a frame

pressed into the picture planepicture plane: The two-dimensional surface where the artist applies paint. while the painting was still wet, and prominent cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. is present along the right side. These attributes, alongside the compositional layout that is nearly identical to four pastel versions, show that it is unlikely that any major format changes have occurred.

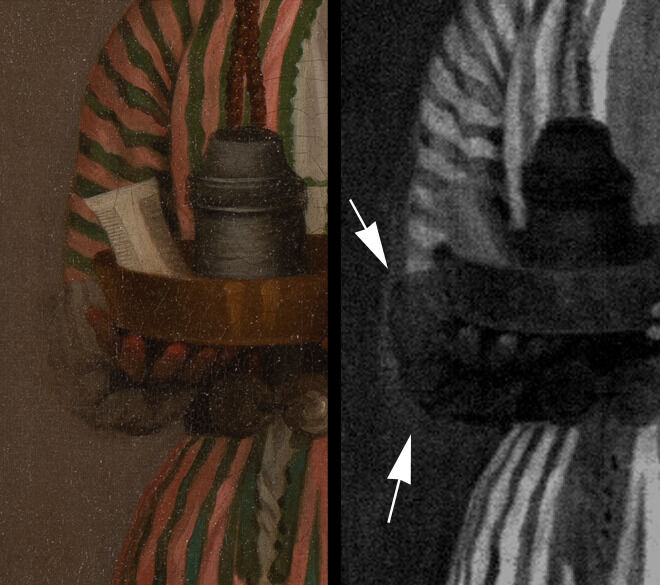

Fig. 5. Detail image of the servant’s proper right arm (left) and an infrared reflectogram (right) captured at 2400 nanometers, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 5. Detail image of the servant’s proper right arm (left) and an infrared reflectogram (right) captured at 2400 nanometers, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 6. Detail image of the adult figure’s proper right arm (top) and an infrared reflectogram (bottom) captured at 2400 nanometers, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 6. Detail image of the adult figure’s proper right arm (top) and an infrared reflectogram (bottom) captured at 2400 nanometers, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 7. Detail image of the drapery of the adult figure (left) and an infrared reflectogram (right) captured at 2400 nanometers, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 7. Detail image of the drapery of the adult figure (left) and an infrared reflectogram (right) captured at 2400 nanometers, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

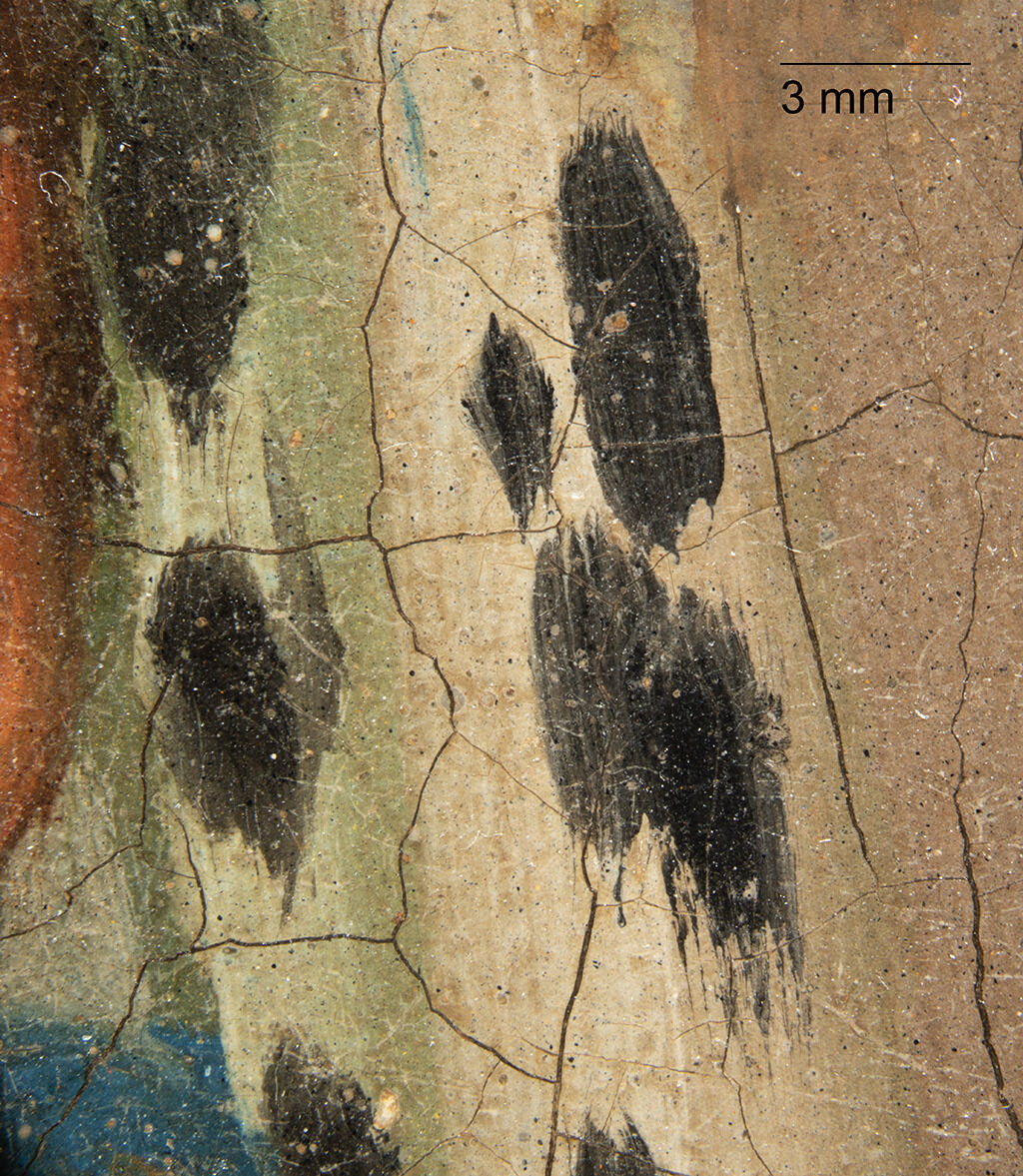

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the gray ground layer visible on the servant’s face, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the gray ground layer visible on the servant’s face, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph in raking light of the incised line along the length of the pipe, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 9. Photomicrograph in raking light of the incised line along the length of the pipe, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

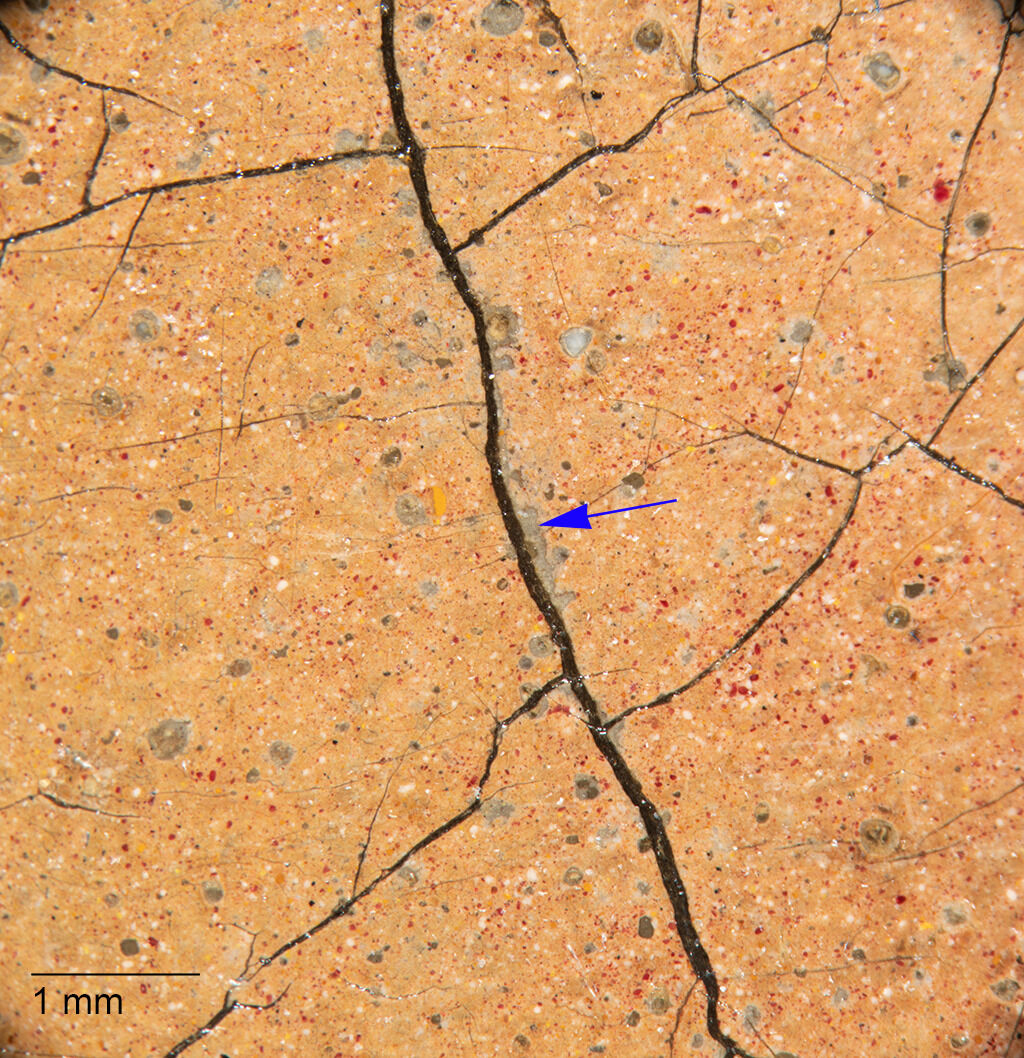

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the lower pink layer beneath the servant’s clothing, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the lower pink layer beneath the servant’s clothing, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

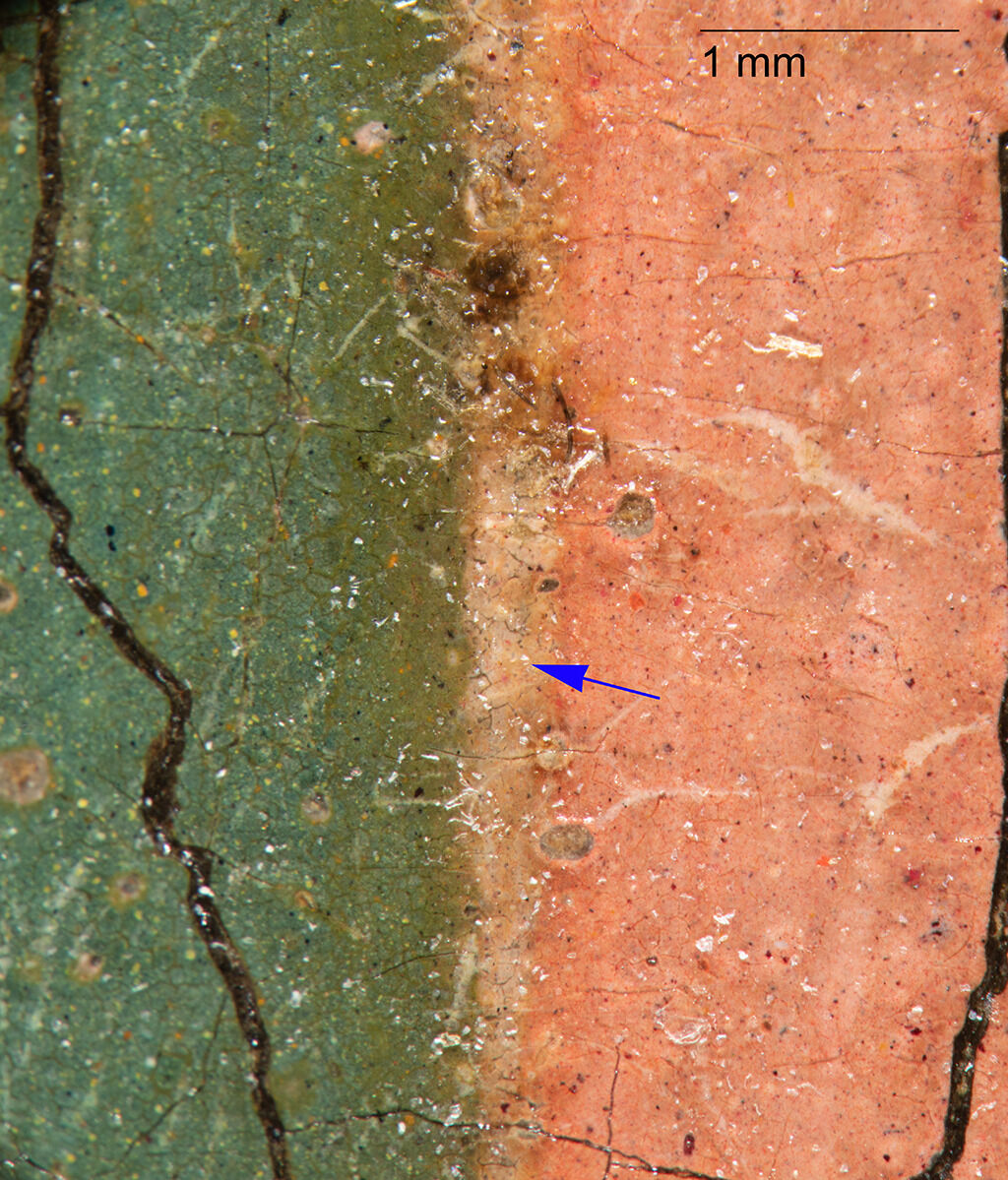

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the highlight colors on the servant’s clothing, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the highlight colors on the servant’s clothing, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 12. Detail image of the reserve around the adult figure’s face, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 12. Detail image of the reserve around the adult figure’s face, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

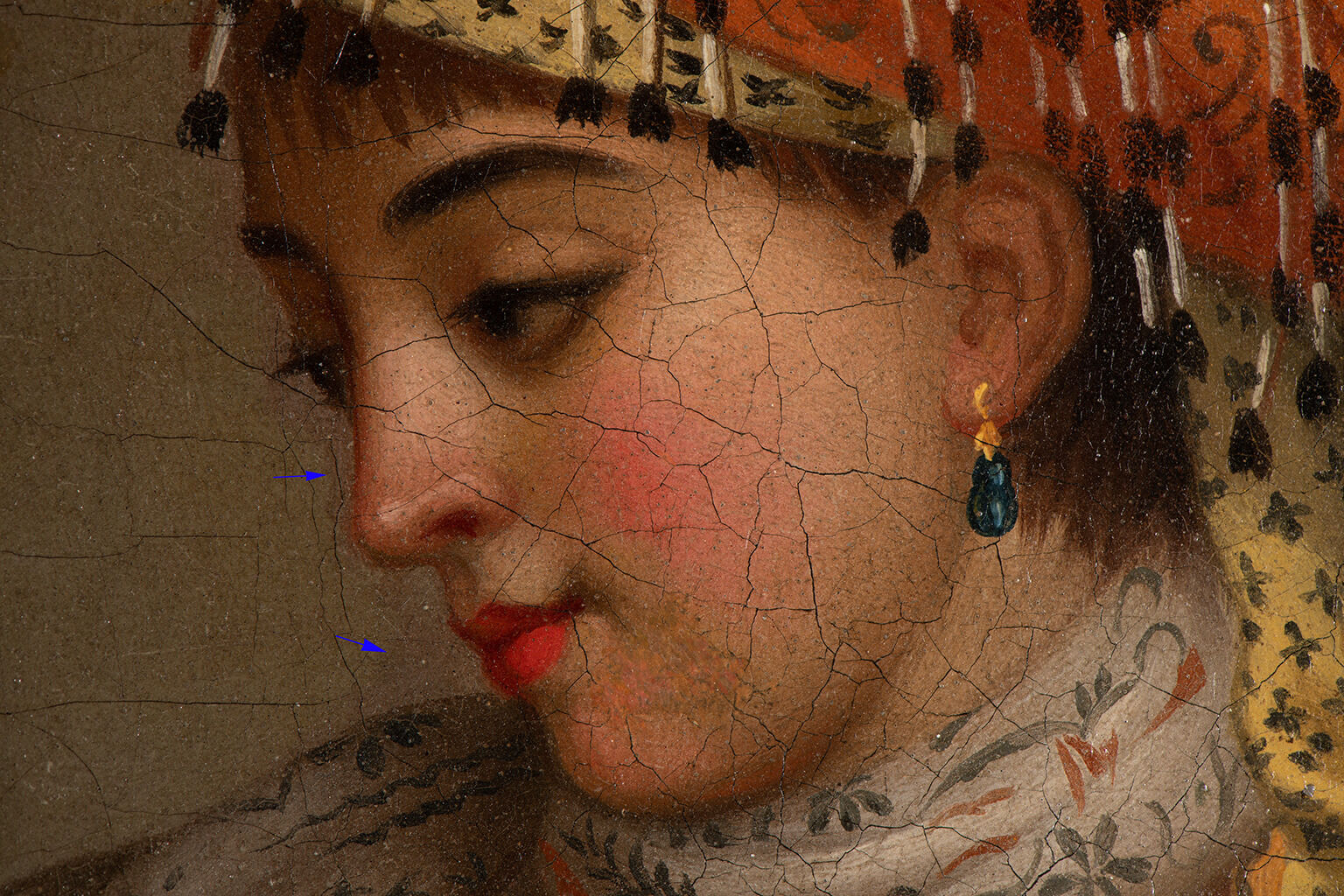

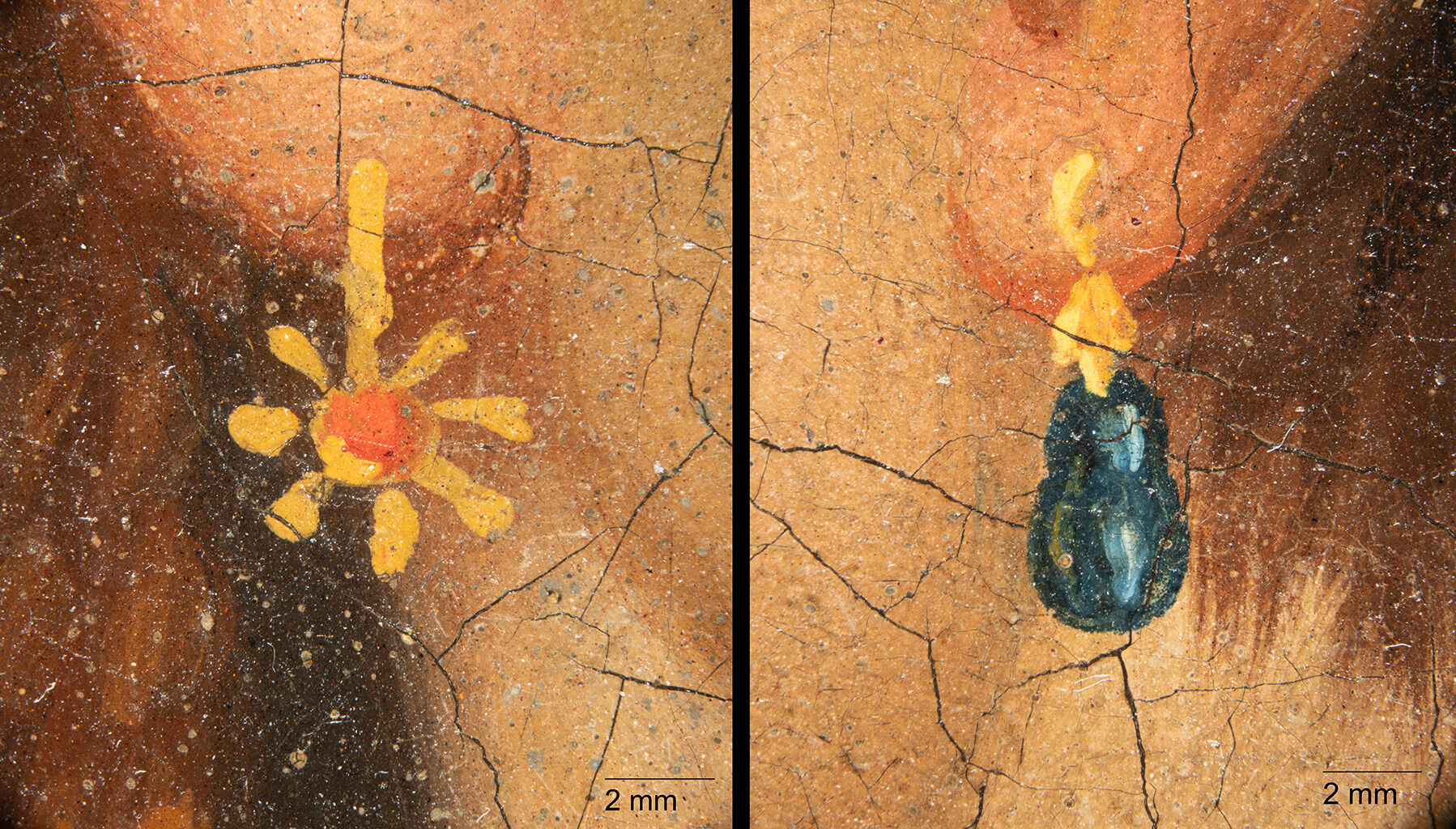

Fig. 14. Photomicrographs of the earrings on the servant (left) and adult figure (right), A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 14. Photomicrographs of the earrings on the servant (left) and adult figure (right), A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 15. Photomicrographs of the fabric details on the adult figure, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Fig. 15. Photomicrographs of the fabric details on the adult figure, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750)

Notes

-

As addressed in the curatorial entry, a major difference between the Nelson-Atkins oil painting and the Geneva pastel is the distance between the figures. See accompanying catalogue entry by Kristel Smentek.

-

A carbon-based underdrawing was found in some of Liotard’s pastel paintings. Leila Sauvage and Cécile Gombaud, “Liotard’s Pastels: Techniques of an 18th-Century Pastellist,” in Studying 18th-Century Paintings and Works of Art on Paper: CATS Proceedings, II, 2014, ed. Helen Evans and Kimberley Muir (London: Archetype Publications, 2015), 39.

-

Liotard’s use of rich colors became more prominent after his travels to Constantinople. Mark Fehlmann, “Orientalism,” in Jean-Etienne Liotard, 1702–1789, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2015), 71.

-

Film-based radiograph no. 076, NAMA conservation file, 56.3.

-

James Roth, treatment report, July 9, 1973, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 56-3.

-

Forrest R. Bailey, treatment report, February 6, 1987, NAMA conservation file, 56-3.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

Probably Jane Westenra (ca. 1710–88), Dowager Viscountess Galway, London, by 1787 [1];

Purchased from her sale, Elegant Household Furniture, Collection of Pictures, By Old Esteemed Masters, Particularly A Capital Landscape and Figures by Berghem, etc. And other Valuable Effects, The Property of A Lady of Fashion, at her house, Situate no. 48, on the South Side of Charles Street, Berkeley Square, Christie’s, London, February 6, 1787, lot 60, as A Turkish lady and her servant, by Robert Monckton-Arundell (1758–1810), 4th Viscount Galway, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK, 1787–1810 [2];

Probably by descent to his son, William Monckton-Arundell (1782–1834), later Monckton, 5th Viscount Galway, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK, by 1810–34;

Probably by descent to his son, George Edward Arundell Monckton-Arundell (1805–76), 6th Viscount Galway, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK, by 1834–76;

Probably by descent to his son, George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell (1844–1931), 7th Viscount Galway, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK, by 1876–1931 [3];

Probably by descent to his son, George Vere Arundell Monckton-Arundell (1882–1943), 8th Viscount Galway, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK, by 1931–43;

To his wife, Lucia Emily Margaret Monckton-Arundell (née White, 1890–1983), 8th Viscountess Galway, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK, by 1943–47 [4];

Sold at her sale, Oil Paintings and Water Colours by Old Masters; English and Continental Porcelain Groups and Figures, Furniture, Objects of Vertu, Miniatures and Books, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK, October 24, 1947, lot 156, as A Coloured Pastel—Interior with Turkish Lady and Servant in richly coloured robes [5];

With Brookfields Successors, Ltd., Stafford, UK, by November 20, 1953 [6];

Purchased at their sale, Old Pictures and Drawings: The Property of Ernest B. Hall, Esq., deceased, removed from Hales Hall, Market Drayton (Sold by Order of the Executors); The Property of the Hon. Charles Nelson and from Other Sources, Christie, Manson and Woods, Ltd., London, November 20, 1953, lot 138, as Two Eastern Girls at a Fountain, by P. and D. Colnaghi, London, stock no. A 3021, as A Turkish Lady with her Attendant, 1953–January 1, 1956 [7];

Purchased from Colnaghi by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1956.

Notes

[1] Cited as a “lady of fashion” in the 1787 Christie’s sale, the owner was likely Jane Westenra (ca. 1710–88), Dowager Viscountess Galway, also known as Lady Galway. Land tax documents from 1786–87 show that Lady Galway owned property in Charles Street, although they do not specify house numbers or who lived in no. 48. “Lady Galway in the London, England, Land Tax Records, 1692–1932,” LMA/4263/01/1157, Ancestry.co.uk. Another less likely possibility for the “lady of fashion” is Lady Galway’s daughter, Mary Monckton (1748–1840), who, until her marriage in 1786, lived with her mother in Charles Street.

[2] The buyer of lot 60 in the 1787 sale was annotated as “Ld Galway,” and has been identified by the Getty Provenance Databases as Robert Monckton-Arundell, 4th Viscount Galway, who was the step-grandson of the painting’s likely seller, Jane Westenra, Dowager Viscountess Galway, also known as Lady Galway. “Lot 60, Sale Catalog Br-A1553,” Getty Provenance Index Databases, Los Angeles. “Ld Galway” only appears once in the sale’s buyers’ list; however, the name “Monckton” appears repeatedly.

[3] In a letter dated February 22, 1924, Robert Langton Douglas (1864–1951), the art critic, prominent dealer, and director of the National Gallery of Ireland, wrote to thank George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscount Galway, for allowing him to visit his estate, Serlby Hall, and see his “paintings by Liotard and Pannini [sic]”. The Liotard that Douglas mentioned might be the Nelson-Atkins painting. “Letter from R. Langton Douglas, 2 Hill Street, Berkeley Square [London] to George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscount Galway; 22 Feb. 1924,” Ga 2 E 180, Correspondence and Personal Papers of George Edmund Milnes Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscount Galway (1844–1931) and Vere Monckton-Arundell, 7th Viscountess Galway (d. 1931), University of Nottingham Libraries, Manuscripts and Special Collections, copy in NAMA curatorial files.

[4] The provenance from 1810 to 1947 is based upon the right of succession and assumes that the painting descended from parent to firstborn child.

[5] Although the picture is listed as a pastel, this is probably erroneous, since the four other pastel versions of the painting are accounted for in other collections at this time. See email from Marcel Rœthlisberger, Professor Emeritus, University of Geneva, to Glynnis Stevenson, the Nelson-Atkins, May 16, 2018, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] Brookfields Successors, Ltd., was a department store and estate liquidation company in Stafford, who consigned the painting to the Christie’s sale of November 20, 1953. Several advertisements in The Staffordshire Advertiser in the 1940s and 1950s show that Brookfield’s Successors also provided funeral director services. By late 1953, Brookfield’s was going out of business and liquidating their stock. See email from Daniel Jarmai, Christie’s Archives, London, to Glynnis Stevenson, the Nelson-Atkins, May 22, 2018, NAMA curatorial files. The William Salt Library in Stafford was unable to provide further information.

[7] See email from MacKenzie Mallon, the Nelson-Atkins, to Jeremy Howard, Head of Research, Colnaghi, June 28, 2017, NAMA curatorial files.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

Jean Etienne Liotard, Lady and her Maid at the Bath (Dame et sa servante au bain), 1738–42, pastel on parchment, 27 11/12 x 20 5/6 in. (71.0 x 53.0 cm), Musée d’art et d’histoire, Geneva.

Jean Etienne Liotard, Lady and her Maid at the Bath (Dame et sa servant au bain), 1738–42, pastel on parchment, 28 1/2 x 22 1/2 in. (72.4 x 57.2 cm), Museum Oskar Reinhart am Stadtgarten, Winterthur.

Jean Etienne Liotard, Lady and her Maid at the Bath (Dame et sa servant au bain), 1750–53, pastel on parchment, 27 2/3 x 22 1/2 in. (70.3 x 56.3 cm), private collection.

Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Costume with Her Servant at the Hammam, ca. 1748–54, pastel on paper mounted to canvas, 27 11/12 x 22 1/12 in. (70.9 x 56.0 cm), Lusail Museum (formerly the Orientalist Museum), Doha, Qatar.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

Paintings by Old Masters, P. and D. Colnaghi and Company, London, April 1954, no. 14, as A Turkish Lady with her Attendant.

European Masters of the Eighteenth Century: Winter Exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts, London, November 27, 1954–February 27, 1955, no. 157, as A Turkish Lady with her Attendant.

The Century of Mozart, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 15–March 4, 1956, no. 67, as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

Acquisitions of 1956, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 1957, no cat., as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

The Age of Louis XV: French Painting 1710–1774, The Toledo Museum of Art, OH, October 26–December 7, 1975; The Art Institute of Chicago, January 10–February 22, 1976; The National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, March 21–May 2, 1976, no. 67, as Dame franque et sa servante.

Vanity Fair: A Treasure Trove from the Costume Institute, The Costume Institute, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, December 12, 1977–September 3, 1978, hors cat.

Orientalism: The Near East in French Painting, 1800–1880, Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, NY, August 27–October 17, 1982; Neuberger Museum, State University of New York College, Purchase, NY, November 14–December 23, 1982, no. 59, A Turkish Lady and her Attendant.

Genre, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 5–May 15, 1983, no. 17, as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

A Glimpse of Rococo France: “The Amorous Proposal” by François Le Moyne, The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, April 4–June 13, 1987, no. 9, as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Casanova: The Seduction of Europe, Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX, August 27–December 31, 2017; Legion of Honor, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, February 10–May 28, 2018; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, July 8–October 8, 2018, no. 51, as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean Etienne Liotard, A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant, ca. 1750,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.322.4033.

A Catalogue of the Elegant Household Furniture, Collection of Pictures, By Old Esteemed Masters, Particularly A Capital Landscape and Figures by Berghem, etc. And other Valuable Effects, The Property of A Lady of Fashion, at her house, Situate no. 48, on the South Side of Charles Street, Berkeley Square (London: Christie’s, February 5–6, 1787), 12, as A Turkish lady and her Servant.

Oil Paintings and Water Colours by Old Masters; English and Continental Porcelain Groups and Figures, Furniture, Objects of Vertu, Miniatures and Books, Serlby Hall, Bawtry, Yorks, By order of the Rt. Hon. the Viscountess Galway (Bawtry, Yorkshire, UK: Henry Spencer and Sons, 1947), 17, erroneously as A Coloured Pastel—Interior with Turkish Lady and Servant in richly coloured robes.

Art Prices Current: A Record of Sale Prices at the Principal London Continental and American Auction Rooms, vol. 26, New Series: August 1947 to July 1949 (London: Art Trade, 1949), A10, erroneously as Pastel, Interior with Turkish Lady and Servant, richly coloured robes.

Catalogue of Old Pictures and Drawings: The Property of Ernest B. Hall, Esq., deceased, removed from Hales Hall, Market Drayton (Sold by Order of the Executors); The Property of the Hon. Charles Nelson and from Other Sources (London: Christie, Manson and Woods, 1953), 18, as Two Eastern Girls at a Fountain.

Paintings by Old Masters, exh. cat. (London: P. and D. Colnaghi, 1954), unpaginated, (repro.), as A Turkish Lady with her Attendant.

B[enedict] N[icholson], “Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions,” Burlington Magazine 96, no. 614 (May 1954): 162.

European Masters of the Eighteenth Century: Winter Exhibition, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1954), 58, as A Turkish Lady with her Attendant.

“The Century of Mozart,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 1, no. 1 (January 1956): 14, 29, 86–88, (repro.), as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

“Special Exhibition: The Century of Mozart,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 23, no. 4 (January 1956): unpaginated, as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

Winifred Shields, “Among the New Acquisitions of the Nelson Gallery of Art: Paintings, Sculptures, and an 18th Century Room Are Added to the Art Treasures,” Kansas City Star 76, no. 113 (January 8, 1956): [1]E, as Turkish Lady with Her Attendant.

“New Acquisition,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 23, no. 5 (February 1956): unpaginated, (repro.), as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

“Accessions of American and Canadian Museums: January–March, 1956,” Art Quarterly 19, no. 3 (Autumn 1956): 305, as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

“Special Exhibition: Acquisitions 1956,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Art) 24, no. 7 (April 1957): unpaginated, as A Turkish Lady and her Attendant.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 115, 263, (repro.), as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

“Treasures of Kansas City,” Connoisseur 145, no. 584 (April 1960): 123, as Turkish Lady with her Attendant.

Art Institute of Chicago, Index to Art Periodicals (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1962), 6:5299, as A Turkish Lady and her attendant.

Dino Fabbri, ed., I Maestri del colore, vol. 240, Liotard (Milan: Fratelli Fabbri Editori, 1966), unpaginated, as Due turche.

Ralph T. Coe, “The Baroque and Rococo in France and Italy,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 531, 539 [repr., in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 63, 71], as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

Ross E. Taggart, “The Charm of Chinoiserie,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 524, 529, (repro.) [repr., in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 56, 61, (repro.)], as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 138, 262, (repro.), as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

Pierre Rosenberg, The Age of Louis XV: French Painting 1710–1774, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1975), 56, (repro.), as Dame franque et sa servante.

Renée Loche, Jean-Étienne Liotard (Geneva: Musée d’art et d’histoire, 1976), 27, as Femme turque et fillette sur des échasses.

Renée Loche, Jean-Etienne Liotard: Genf 1702–1789, trans. Brigitte Zehmisch, eds. Felix Baumann and Romy Storrer, exh. cat. (Zurich: Kunsthaus Zürich, 1978), 25, as Türkischen Dame mit Dienerin.

Renée Loche and Marcel Rœthlisberger, L’opera completa di Liotard (Milan: Rizzoli Editore, 1978), no. 51, pp. 93, 127, as Dama franca vestita alla turca con domestica.

Donald A. Rosenthal, Orientalism: The Near East in French Painting, 1800–1880, exh. cat. (Rochester, NY: Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, 1982), 18–19, 167, (repro.), as A Turkish Lady and her Attendant.

Donald Hoffmann, “More about Oudry,” Kansas City Star 103, no. 292 (August 28, 1983): 8E.

Genre, exh. cat. (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1983), 12, as A Turkish Lady and Her Attendant.

Frans Grijzenhout, Liotard in Nederland, exh. cat. (Utrecht, The Netherlands: Uitgeverij Kwadraat, 1985), 15, as Westerse vrouw in Turkse kleding met een dienstmeisje.

Brian de Breffny, “Liotard’s Irish Patrons,” Irish Arts Review 4, no. 2 (Summer 1987): 32.

Jennifer Gordon Lovett, A Glimpse of Rococo France: “The Amorous Proposal” by François Le Moyne, exh. cat. (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1987), unpaginated, (repro.), as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Ellen R. Goheen, The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), 16, 68–69, (repro.), as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Auguste Boppe, Les peintres du Bosphore au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: ACR Édition Internationale, 1989), 72, 74, 76, as Dame franque et sa servante.

Marcel G. Rœthlisberger, “The Unseen Faces of Jean-Etienne Liotard’s Drawings,” Drawing 11, no. 5 (January–February 1990): 98.

Nicholas H. J. Hall, ed., Colnaghi in America: A Survey to Commemorate the First Decade of Colnaghi New York (New York: Colnaghi, 1992), 129, as A Frankish Woman and her Servant.

Anne de Herdt, Dessins de Liotard: Suivi du catalogue de l’œuvre dessiné, exh. cat. (Geneva: Musée d’art et d’histoire, 1992), 70, as Dame franque et son esclave au hammam.

Aleth Jourdan et al., Frédéric Bazille: Prophet of Impressionism, trans. John Goodman, exh. cat. (New York: Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1992), 74–75, (repro.), as Frankish Woman and Her Servant and Femme Franque et sa servante.

Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 74, as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, 1993), 186, (repro.), as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Old Master Drawings (London: Christie’s, July 4, 1995), 74, as A Woman in Turkish Costume in a ‘hamam’ instructing her Servant.

Patricia Pate Havlice, World Painting Index: Second Supplement, 1980–1989 (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1995), 2:1316, as A Frankish woman and her servant.

Harold Koda, Extreme Beauty: The Body Transformed, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2001), 142–43, (repro.), as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Old Master and 19th Century Drawings (New York: Christie’s, January 23, 2002), 104, as A woman in Turkish costume in a ‘hammam’ instructing her servant.

Linda Abrams, Vanity: The Art of Looking Good (New York: Red Rock Press, 2003), 109, 115, (repro.), as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of pastellists before 1800 (London: Unicorn Press, 2006), 352, (repro.), as Dame en turque avec servant.

Claire Stoullig et al., Jean-Étienne Liotard, 1702–1789: Masterpieces from the Musées d’art et d’histoire of Geneva and Swiss Private Collections, exh. cat. (Paris: Somogy Éditions d’Art, 2006), 11.

Abigail Solomon-Godeau, “Jean-Etienne Liotard: Facing the Enlightenment,” Art in America 94, no. 10 (November 2006): 152.

Marcel Rœthlisberger, “Liotard’s Sleeping Venus after Titian,” artibus et historiae, no. 55 (2007): 153, as Lady in Turkish dress and her slave.

Deborah Emont Scott, ed., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection, 7th ed. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2008), 98, (repro.), as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Marcel Rœthlisberger and Renée Loche, Liotard: Catalogue, Sources et Correspondance (Doornspijk, The Netherlands: Davaco, 2008), no. 68; pp. 1: 31–32, 40–41, 115, 275–76, 464; 2: unpaginated, (repro.), as Dame et sa servante au bain and Dame et son esclave au bain.

Old Masters and 19th Century Art: Including Paintings, Drawings and Watercolours (London: Christie’s, July 7, 2009), 132, as A lady in Turkish costume with her servant at the hammam.

Neil Jeffares, “Two English portraits by Liotard: Lady Anne Somerset and Catherine, Lady Hawke,” British Art Journal 15, no. 3 (Spring 2015): 7, as Dame et sa servant au bain.

Thea Burns and Philippe Saunier, The Art of the Pastel (New York: Abbeville Press, 2015), 97, as Lady and Her Servant at the Bath.

Beatrice Gullström et al., Jean-Etienne Liotard: 1702–1789, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 2015), 169.

Didier Rykner, “Une peinture de Liotard acquise par le Rijksmuseum,” La Tribune de l’art (December 2016): unpaginated.

Frederick Ilchman et al., eds., Casanova: The Seduction of Europe, exh. cat. (Boston: MFA Publications, 2017), 99, 109–11, 284n25, 306, (repro.), as A Frankish Woman and Her Servant.

Karen Wilkin, “Art: Casanova in Forth Worth,” New Criterion 36, no. 2 (October 2017): 50.

Duncan Bull, “Recent Acquisitions,” Rijksmuseum Bulletin 66, no. 1 (2018).

Old Master and British Works on Paper (London: Sotheby’s, July 3, 2019), n7.

Stephen Cribb and Steve Huxham, Out of the Mud: The History of the Worshipful Company of Pattenmakers, ed. Richard Kottler (Inverness, UK: Phillimore Book Publishing, 2020).