![]()

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later

| Artist | Jean-Baptiste Greuze, French, 1725–1805 |

| Title | Head of a Girl |

| Object Date | ca. 1770 or later |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 17 1/2 x 14 1/2 in. (44.5 x 36.8 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 31-55 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Richard Rand, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.318.5407.

MLA:

Rand, Richard. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.318.5407.

This painting depicts the bust of an adolescent girl looking over her left shoulder at the viewer. Her reddish-blonde hair, parted in the middle, braided and coiled at the top of her head, is held in place by a blue ribbon; loose strands fall next to her right eye. She wears a white chemisechemise: A plain, thin white cotton garment with short sleeves and sometimes a low neckline. and an off-white scarf that fall loosely to reveal her bare shoulder and neck. A strong light illuminates her from the left, throwing her form into strong relief against the dark background. The compositional forms—the curves of the drapery folds; the rounded contours of the model’s shoulder, neck, and cheeks; the coiled braid of her hair—echo the oval format of the canvas. The artist’s smooth and creamy brushwork enhances the intimacy of the conceit. Indeed, the effect is startlingly intimate, as if we have surprised the girl from behind, causing her to turn suddenly, although her expression is more one of pleasing recognition than of fear or consternation.

Fig. 3. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, A Girl with a Dead Canary, 1765, oil on canvas, 21 x 18 1/8 in. (53.3 x 46 cm), Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh. Bequest of Lady Murray of Henderland 1861, NG

Fig. 3. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, A Girl with a Dead Canary, 1765, oil on canvas, 21 x 18 1/8 in. (53.3 x 46 cm), Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh. Bequest of Lady Murray of Henderland 1861, NG

Fig. 4. Jean Baptiste Greuze, Young Girl Seen from Behind, ca. 1770–80, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 14 15/16 in. (46 x 38 cm), Musée Fabre, Montpellier

Fig. 4. Jean Baptiste Greuze, Young Girl Seen from Behind, ca. 1770–80, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 14 15/16 in. (46 x 38 cm), Musée Fabre, Montpellier

Notes

-

In 1769, Greuze was voted a member of the Royal Academy. However, he was humiliated to discover that his colleagues had not received him as a history painter but as a genre painter. Enraged, he did not exhibit at the Salon again until 1800.

-

See Bernadette Fort, “The Greuze Girl: The Invention of a Pictorial Paradigm,” in Philip Conisbee, ed., French Genre Painting in the Eighteenth Century (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2007), 129.

-

Alte Meister, 1. Teil; Old Master Paintings, Part 1 (Vienna: Dorotheum, October 6, 2009), lot 114, as La Pudeur Agacante—Die sittsame Provokation. According to the auction catalogue, this version had been in a Swedish private collection since about 1790.

-

Edgar Munhall had previously considered the Kansas City painting “a contemporary copy, not by Greuze himself but probably by one of his students” (Munhall to the author, September 9, 2013), but revised his opinion after the cleaning of the painting: “I am convinced that in its cleaned state this Head of a Girl is a genuine work by Jean-Baptiste Greuze” (Munhall to the author, January 5, 2015). Yet another version of the Kansas City painting—by all appearances a copy—appeared at auction in 1991 in Lille, implausibly attributed to Ernest Dupont (1816/1825–1885); Art d’Afrique et d’Asie, Jouets et Poupées de Collection, Armes Anciennes, Objets d’Art et de Bel Ameublement, Céramiques, Bijoux; Tableaux Anciens, Modernes, Mobilier des XVIIe, XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles (Lille: Mercier, Velliet, Thullier, Duhamel, December 15, 1991), no. 218.

-

For example, several changes may be observed in the edge of the dress below the proper left shoulder and in the contour of the hair at the back of the head; See Scott A. Heffley, “Discoveries of Technique in Greuze’s Head of a Girl, 31-55,” July 29, 2014, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Emma Barker, “Reading the Greuze Girl: The Daughter’s Seduction,” Representations 117 (Winter 2012): 86–119. Barker noted that the first use of the term “Greuze Girl” appears to have been by John Rivers in “Of the Greuze Girl,” chapter 1 of his book Greuze and His Models (London: Hutchinson, 1912).

-

Thomas E. Crow, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth-Century Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1985), 153.

-

On Greuze’s relationship to this tradition, see Melissa Percival, The Appearance of Character: Physiognomy and Facial Expression in Eighteenth-Century France (London: W. S. Maney, 1999), 113–30.

-

Edgar Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, exh. cat (London: Merrell, 2002), no. 52, pp. 158–59. For other examples, see nos. 51 and 54.

-

Dagmar Hirschfelder, Tronie und Porträt in der niederländischen Malerei des 17. Jahrhunderts (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2008).

-

“This child is crying about something else, I tell you”; in John Goodman, ed. and trans., Diderot on Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 1:96–100. Barker, in “Reading the Greuze Girl,” has challenged the commonly held interpretation.

-

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, French Eighteenth-Century Painters: Watteau, Boucher, Chardin, La Tour, Greuze, Fragonard, trans. Robin Ironside (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1981), 248.

-

Chefs-d’œuvre du Musée Fabre de Montpellier, exh. cat. (Lausanne: Fondation de l’Hermitage, 2006), no. 32.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.318.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.318.2088.

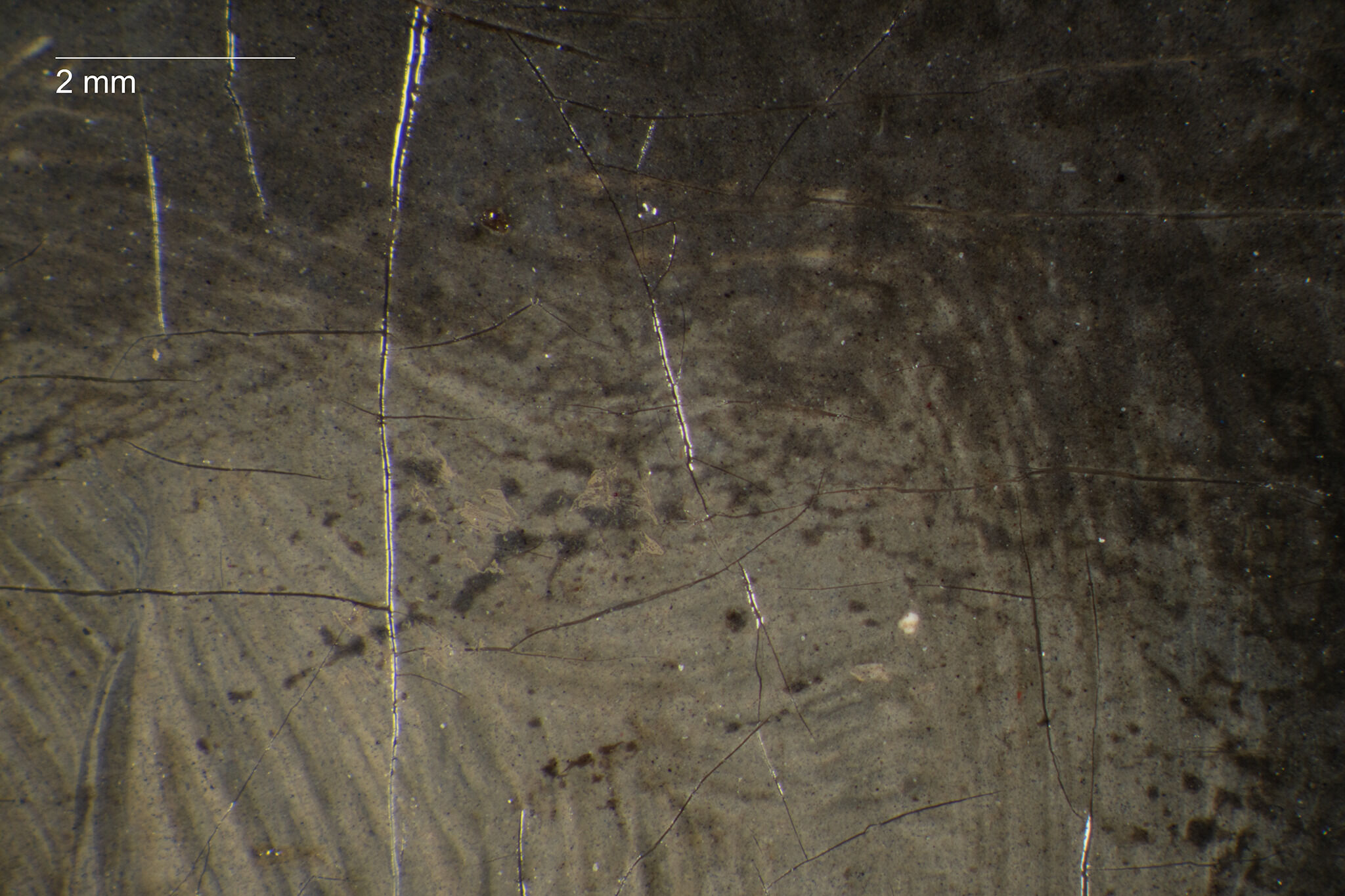

Although there are few opportunities to study the original canvas or the painting edges because the painting has been linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive., radiographyX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. confirms the presence of a plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. fabric with numerous weave irregularities (Fig. 5).2Film-based radiograph no. 564, NAMA conservation file, 31-55. Stretcher cracksstretcher cracks: Linear cracks or deformations in the painting’s surface that correspond to the inner edges of the underlying stretcher or strainer members. at the perimeter edges of the painting do not align with the location of the underlying support members, indicating that the current stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging. is a modern replacement. However, the combination of the stretcher cracks and cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. (right, left, and bottom edges) suggests that the dimensions of the painting have not been significantly altered.

Although Greuze occasionally painted on canvases prepared with a double groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer.,3Humphrey Wine, The Eighteenth-Century French Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2018), 221–42. only a single layer of white ground is evident between the cracks of the Nelson-Atkins painting. No underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. is detected beneath the paint layers using infrared reflectography (IRR)infrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. or examination with the stereomicroscope. Greuze initially blocked in the figure with preliminary washes of gray and brown, and many of these initial layers remain visible and provided the basis for the shadows, as illustrated by the proper right eye in Figure 6. The sitter’s smooth skin and rosy cheeks are rendered with opaque, fluid layers of peach and pink, applied with light crisscrossing movements of the brush. In the artist’s modelling of the face, back, and shoulder, he applied scumbles—cool, pale gray in color—to establish the mid-tones between highlights and shadow. Highlights on the forehead and shoulder were thickly painted with loose, diagonal brushwork that produced some low impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges.. Light, painterly touches of bright red, pink, and magenta, applied wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface., delineate the lips, while subtle strokes of bright blue are evident at the corner of the mouth and inner edge of the proper right eye (Figs. 6, 7). In the final stages of painting, Greuze applied strokes of semitransparent orange to accent the sitter’s neck, eyebrows, and the part of her hair.

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the proper right eye, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the proper right eye, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later), showing painterly touches of bright red, pink, and magenta on the lip as well as bright blue strokes at the lower right corner

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later), showing painterly touches of bright red, pink, and magenta on the lip as well as bright blue strokes at the lower right corner

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later), showing the thickly painted folds of the garment at the lower left

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later), showing the thickly painted folds of the garment at the lower left

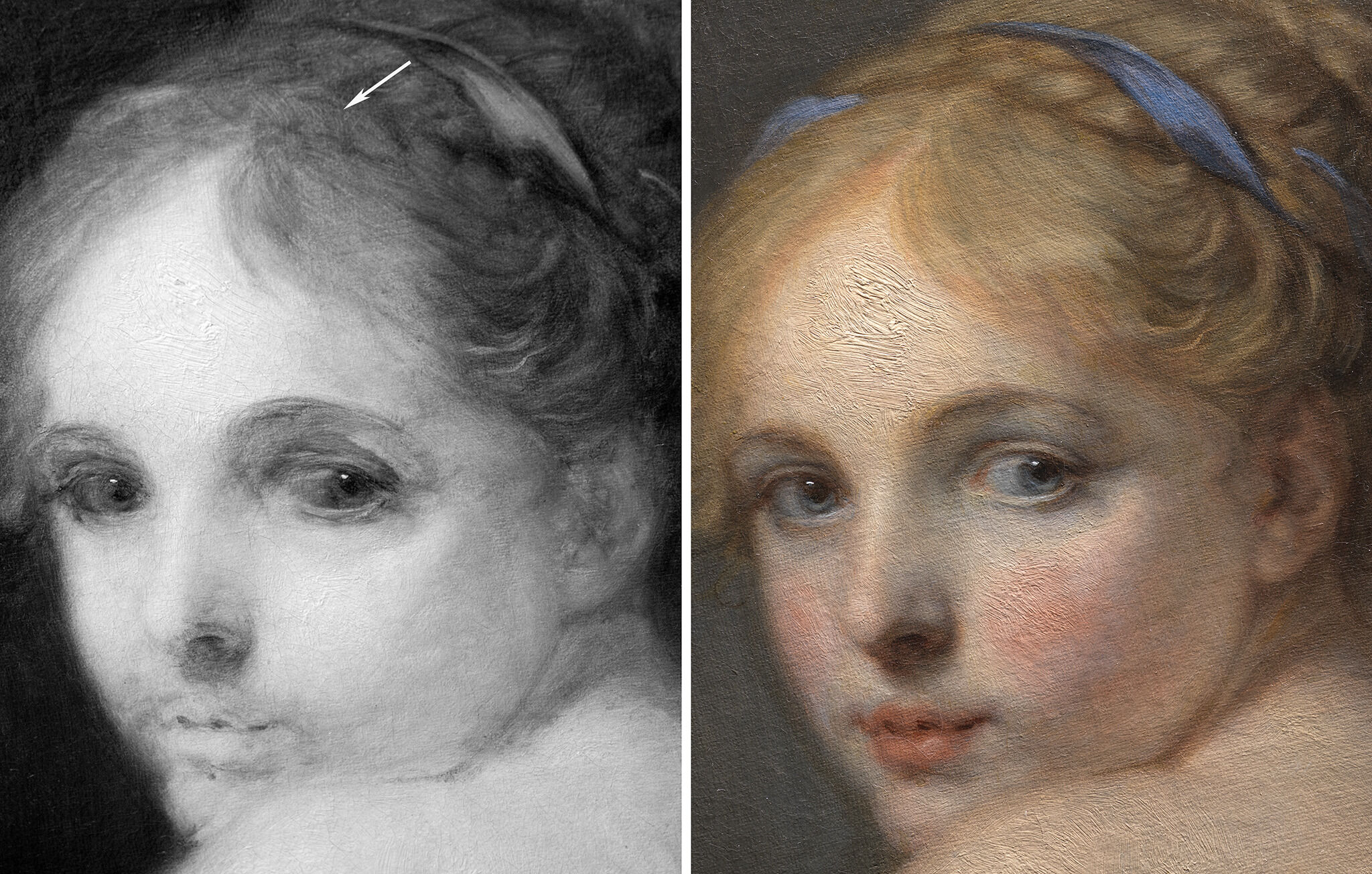

Pentimentipentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind." reveal that Greuze made several adjustments to the composition. The braid adorning the sitter’s head was initially positioned roughly one centimeter lower; the pentimento associated with this shift is faintly visible to the naked eye and also evident with infrared reflectography (Fig. 11). Underlying paint strokes reveal that the thick contours of the beige garment once dropped slightly, approximately two centimeters, at the center of the sitter’s back (Fig. 12). This artist change is also readily visible in the radiograph (Fig. 5). Lastly, Greuze added light gray background paint to the hair at the nape of the sitter’s neck, cropping the hair by roughly half of a centimeter (Fig. 13).

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the gray background paint overlapping the sitter’s garment at her proper right shoulder, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the gray background paint overlapping the sitter’s garment at her proper right shoulder, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later)

Fig. 11. The pentimento of the braid’s earlier position is evident in the reflected infrared digital photograph (left) and raking illumination detail (right), Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later).

Fig. 11. The pentimento of the braid’s earlier position is evident in the reflected infrared digital photograph (left) and raking illumination detail (right), Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later).

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of a thick, underlying paint stroke that reveals the former drape of the garment at the sitter’s back, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of a thick, underlying paint stroke that reveals the former drape of the garment at the sitter’s back, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later)

Fig. 13. Detail of a pentimento at the back of the sitter’s hair, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later)

Fig. 13. Detail of a pentimento at the back of the sitter’s hair, Head of a Girl (ca. 1770 or later)

Notes

-

James Thompson, ”Jean-Baptiste Greuze,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 47, no. 3 (1989): 47. In his discussion of oval formats, Thompson describes how “the artist is forced to demonstrate his or her virtuosity in an instinctive, felicitous inner sequence of curves and countercurves that must relate in an occult balance to the outer shape of the picture.”

-

Film-based radiograph no. 564, NAMA conservation file, 31-55.

-

Humphrey Wine, The Eighteenth-Century French Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2018), 221–42.

-

A clear instance of a fugitive pigment on a work by Greuze is A Child with an Apple (ca. 1800; National Gallery, London), in which a yellow lake has faded and caused the green apple to now appear blue. See David Saunders and Jo Kirby, “Light-induced Colour Changes in Red and Yellow Lake Pigments,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 15 (1994): 81.

-

Scott Heffley, November 2014, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 31-55.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

Probably with [Baron] Nicolas (né Falsenburg, 1882–1952) and Paula (née Schaposchnikoff, d. after 1973) de Koenigsberg, Moscow and Paris [1];

With Bachstitz Gallery, New York, stock no. Ru-63, as Portrait of a Young Girl Looking Over her Shoulder, by January 26, 1931 [2];

Purchased from Bachstitz Gallery, through Harold Woodbury Parsons, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1931.

Notes

[1] The Koenigsberg (Königsberg) collection is listed on Kurt Walter Bachstitz’s invoice to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (see NAMA curatorial file). It is unclear whether they were acting as dealers or if they owned this painting personally. A “Koenigsberg, Paris” (along with Wildenstein and Co., New York) is listed in the provenance of Jean Baptiste Greuze’s Portrait of a Young Woman, sold at Important Old Master Paintings and European Works of Art, Sotheby’s, New York, January 25–26, 2007, lot 97. Wildenstein believes that this is a reference to the art dealers Nicolas and Paula (née Schaposchnikoff) de Koenigsberg, Russian-born émigrés who specialized in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French art. See email from Wildenstein and Co., Inc., New York, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, October 26, 2020.

See also Larissa Murray and Anatol Shmelev, “Basily Treasures at the Hoover Institution,” Slavic and East European Information Resources 17, no. 3 (2016): 132–50, for more on the De Koenigsbergs and the myths surrounding Nicolas’ claim to being a Russian land-owning baron. The authors also note that, during the window the De Koenigsbergs likely had the painting, they were selling art from Russian collections.

[2] According to a note in the Bachstitz Gallery Archive, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Box 15, folder 19 (copy in NAMA curatorial file), the Bachstitz Gallery acquired the painting in New York in January 1931. Bachstitz Gallery began negotiating the painting’s sale to the Nelson-Atkins by January 26, 1931. See letter from J. C. Nichols, NAMA, to Arthur M. Hyde, NAMA, January 26, 1931, NAMA curatorial file.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Young Girl Seen from Behind, ca. 1770–80, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 14 15/16 in. (46 x 38 cm), Musée Fabre, Montpellier.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Young Girl, oil on canvas, 18 15/16 x 15 9/16 in. (48 x 39.5 cm), sold at Van Gogh, Gauguin, Renoir: Collection Mme Théa Sternheim, La Hulpe, près Bruxelles, Frederik Muller et Cie, Amsterdam, February 11, 1919, no. 14.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, A Young Girl, pastel on paper, 17 3/10 x 13 4/5 in. (44 x 35 cm), Gösta Serlachius Museum, Mänttä, Finland.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl Looking Up, undated, red chalk, framing lines in brown and black ink, 14 x 11 3/16 in. (35.6 x 28.4 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Known Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Demure Protest, ca. 1785, oil on canvas, 18 1/2 x 15 7/16 in. (47 x 39 cm), sold at Alte Meister, I. Teil; Old Master Paintings, Part I, Dorotheum, Vienna, October 6, 2009, no. 114.

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Youth Seen from Behind, second half of the eighteenth century, oil on canvas, 18 1/8 x 15 in. (46 cm x 38 cm), Museo nacional del Prado, Madrid.

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Portrait of a Young Woman, oil on canvas, 19 15/16 x 15 3/4 in. (49 x 40 cm), sold at Art d’Afrique et d’Asie, Jouets et Poupées de Collection, Armes Anciennes, Objets d’Art et de Bel Ameublement, Céramiques, Bijoux; Tableaux Anciens, Modernes, Mobilier des XVIIe, XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles (Lille: Mercier, Velliet, Thuillier, Duhamel, December 15, 1991), no. 218, as attributed to Ernest Dupont, Portrait de jeune femme.

Follower of Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Portrait of a Young Woman, undated, oil on canvas, 17 1/2 x 14 1/4 in. (44.5 x 36.2 cm), sold at Fine Art: Old Masters To Contemporary, Sotheby’s, New York, June 13–14, 2007, lot 128, as Portrait of a Young Woman.

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Young Girl, 17 9/10 x 14 3/4 in. (45.5 x 37.5 cm), oil on canvas, with Gottschewski und Schäffer, Berlin, 1928.

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Portrait of a girl in the lid of a round ivory box, 2 1/4 x 2 19/20 in. (8.3 x 7.5 cm), sold at Kunst-Sammlung und Innen-Einrichtung der Villa des Geh. Kommerzienrats Hammerschmidt: Französisches und deutsches Porzellan des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts, altdeutsche Gläser, Arbeiten in Silber, Halbedelsteinen, Elfenbein, Bronzen, Email, Cloisonnʹe, Bildnisminiaturen, Dosen; Bücher, Speiseservice, Gläsergarnituren, Barock-Sandsteinfiguren, reiches Antikes und neuzeitliches Mobiliar, Beleuchtungskörper, Dekorationen, Gemälde alter und neuzeitlicher Meister, Perser-Teppiche, Bahnen-Teppiche, Kunsthaus Lempertz, Cologne, December 4–7, 1928, no. 405, as Mädchenbildnis im Deckel einer runden Elfenbeindose.

Henri Legrand, after Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Modest Provocation, engraving, 16 7/10 x 20 2/3 in. (42.5 x 52.5 cm), offered on Antique-Authie.com, as of November 2020, https://antique-authie.com/boutique-brocante-vintage/tableaux-et-gravures/estampe-la-pudeur-agacante-dapres-greuze-grave-par-henri-legrand/

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

Kansas City’s Art Purchases, Kansas City Art Institute, October 1931, no cat., as Portrait of a Young Girl Looking Over her Shoulder.

Portraits from Four Centuries, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, February 1957, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Head of a Girl, ca. 1770 or later,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.318.4033.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Large Crowd at Art Institute Sees Seven Canvases Under Consideration for the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and H. A. Botkin’s Ultra-Modern Water Colors; Pupils of Nora LaMar Moss in Recital,” Kansas City Times 94, no. 10 (January 12, 1931): 6.

Possibly “Half-Million for Art: A Rembrandt in New Purchases for Nelson Gallery; Works Acquired Should Not Be Judged Solely by Their Financial Value, Herbert V. Jones Points Out,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 156 (February 20, 1931): 3.

“Kansas City Gets $1,000,000 Art Here: William Rockhill Nelson Trust Buys Paintings by Rubens, Rembrandt and Others. Guelph Objects Included Treasures to Be Placed in New Structure Being Built by Publisher’s Endowment,” New York Times 80, no. 26,690 (February 20, 1931): 16.

“A Treasure Island of Art Masterpieces; From Kansas City’s Art Purchases: Now on Display at the Kansas City Art Institute,” [Kansas City Visitor?] (October 1931): 6, (repro.), as Portrait of a Young Girl Looking Over Her Shoulder.

“Art Tangle for Others: Nelson Trustees Say They Are Not Involved in Dispute; ‘Old Parr’ Was Bought in a Group and the Legal Differences Are for Agent and Dealer to Solve,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 100 (December 26, 1931): 12.

“What to See In Kansas City: A guide to principal Points of Interest Presented in the Style of A Baedeker,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 101 (December 27, 1931): 3C, as Portrait of a Young Girl.

“Treasure in Lore of Art: ‘Read,’ says Parsons to Those Who Would Appreciate Works; Kansas City Has the Finest Museum In the Country, Adviser for the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery Asserts,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 10 (January 12, 1932): 2.

“Frank Lauder’s Slides made by Color Photography are Something New in the Field of Art Education Here,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 54 (March 3, 1932): 6.

“Suit over ‘Old Parr:’ Owner Asks $20,000 of Dealer Who Sold Canvas; The Trustees of the Nelson Gallery Are Not Involved in Action, as the Sale to Them Is Not Questioned,” Kansas City Star, 53, no. 253 (May 28, 1933): 3A.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 13, 21, as Portrait of a Young Girl.

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, 30, 45, (repro.), as Portrait of a Young Girl.

Minna K. Powell, “The First Exhibition of the Great Art Treasures: Paintings and Sculpture, Tapestries and Panels, Period Rooms and Beautiful Galleries Are Revealed in the Collections Now Housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum—Some of the Rare Objects and Pictures Described,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 84 (December 10, 1933): 4C, as Portrait of a Girl.

Paul V. Beckley, “Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 193 (December 17, 1933): 2C, as Portrait of a Young Girl.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 41, 45, 137, (repro.), as Portrait of a Young Girl.

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 168, as Head of a Girl.

“French Art is Topic: Sixth in Gallery Lecture Series to be Given Tomorrow; Rare Brocades and Silks Will Be Discussed by Paul Gardner in Session on Wednesday,” Kansas City Star 68, no. 61 (November 17, 1947): 16.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 55.

“Mezzanine Galleries Portraits from Four Centuries,” Gallery News (The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts) 24, no. 5 (February 1957): unpaginated.

Winifred Shields, “The Inner-Self of Portrait Subjects Shown on Canvass [sic],” Kansas City Star 77, no. 134 (February 1, 1957): 6.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 260, as Head of a Girl.

Ralph T. Coe, “The Baroque and Rococo in France and Italy,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 539 [repr., in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 71], as Head of a Girl.

Alte Meister, I. Teil; Old Master Paintings, Part I (Vienna: Dorotheum, October 6, 2009), 224.