![]()

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765

| Artist | Jean-Baptiste Greuze, French, 1725–1805 |

| Title | The Nursemaids |

| Object Date | ca. 1765 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Les Sevreuses; The Dry Nurses |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 12 1/2 x 15 5/8 in. (31.8 x 39.7 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 31-61 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Richard Rand, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.5407.

MLA:

Rand, Richard. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.5407.

At the Paris SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. of 1765, Greuze exhibited a painting representing a rustic interior in which two women attend a group of six children. The picture was not listed in the Salon livret, the small catalogue printed for the benefit of visitors, meaning it likely was a late addition to the sixteen paintings, pastels, and drawings that the artist submitted that year.1Explication des Peintures, Sculptures, et Gravures, de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale, exh. cat. (Paris: Jean-Th. Herissant, 1765), nos. 110–25. The accounts of the picture offered by critics present a detailed description of the composition. Denis Diderot (1713–84) was particularly specific in his review of the Salon that year:

Moving from right to left, three upended barrels in a row; a table; on this table a bowl, a small saucepan, a cauldron, and other household utensils. In the foreground, a child leading a dog by a leash; to this child is turned the back of a peasant woman in whose lap a little girl is asleep. Further back, an older child holding a bird; one sees a drum at his feet. The bird’s cage is attached to the wall; then another seated woman grouped with three small children; behind her, a cradle. On the foot of the cradle a kitten; on the floor, beneath it, a chest, a pillow, some sticks, and other gear associated with cottages and nursemaids.2“En allant de la droite à la gauche, trois tonneaux debout sur une même ligne; une table; sur cette table une écuelle, un poëlon, un chaudron, et autres ustensiles de ménage. Sur le plan antérieur, un enfant qui conduit un chien avec une corde; à cet enfant tourne le dos une paysanne, sur le giron de laquelle une petite fille est endormie. Plus vers le fond, un assez grand enfant qui tient un oiseau, on voit un tambour à ses pieds, et la cage de l’oiseau attachée au mur. Ensuite une autre femme assise et grouppée [sic] avec trois petits enfans [sic]; derrière elle un berceau; sur le pied du berceau un chaton; à terre, au-dessous, un coffre, un oreiller, des bâtons de coteret [sic] et autres agrès de chaumières et de sevreuses”; Denis Diderot, Salon de 1765, 1765; repr., in Jacques-André Naigeon, ed., Œuvres de Denis Diderot (Paris: Deterville, 1799–1800), no. 121, pp. 13:194–95; translation by John Goodman, Diderot on Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 1:109–10.

The picture in Kansas City conforms closely to Diderot’s account (although the birdcage is not attached to the wall but rests on a table) and matches almost precisely the reproductive engraving issued in 1769 by Pierre Charles Ingouf (1746–1800) (Fig. 1). Entitled Les Sevreuses—usually translated as “The Nursemaids”—the engraving reverses the orientation of the composition, as typically happens in the printing process.3Yves Bruand and Michèle Hébert, Inventaire du Fonds Français: Graveurs du XVIIIe Siècle (Paris: Bibilothèque nationale, 1970), no. 15, p. 11:609. The principal difference between the Nelson-Atkins painting and the engraving occurs at the bottom of the composition, where the painting is missing several objects—some planks, a ball, and a bowl and spoon—that appear in the print. Technical evidence confirms that the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. and a small amount of the bottom edge were trimmed at some point, perhaps when it was relined; it is likely that the painting originally included the extra floor space and objects recorded in the engraving.4Conservation records indicate that the painting has been relined, and a radiograph reveals the location of a fill along the bottom edge, ranging between 1/8 and 3/8 inch in height, that extends to the edge of the picture plane across the length of the bottom edge. See the accompanying technical entry by Mary Schafer.

For many years following its acquisition, the Kansas City painting was assumed to be the picture Greuze had exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1765. Early authorities such as Smith (cited above) and Jean Martin and Charles Masson, who wrote the first catalogue raisonné of the works of Greuze in 1905, identified the painting in the Rothschild collection—i.e., the picture now in Kansas City—as the original sold in 1785.10J[ean] Martin and Ch[arles] Masson, Le Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint et Dessiné de Jean-Baptiste Greuze, in Camille Mauclair, Jean-Baptiste Greuze (Paris: H. Piazza, [1905]), no. 207, p.16. Later writers such as Anita Brookner and Carol Duncan, focusing more on interpreting the imagery of The Nursemaids than its authorship, also accepted the Nelson-Atkins painting as authentic.11Anita Brookner, Greuze: The Rise and Fall of an Eighteenth-Century Phenomenon (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1972), 64, 106; Carol Duncan, ”Happy Mothers and Other New Ideas in French Art,“ Art Bulletin 55, no. 4 (December 1973): 576–77. Nevertheless, Edgar Munhall, the leading recent authority on Greuze, did not include the painting in his groundbreaking Greuze exhibition of 1976–77 and later consistently maintained that it was a copy of the lost original.12Jean Baptiste Greuze 1725–1805, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, December 1, 1976–January 23, 1977; The California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, March 5–May 1, 1977; the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, June 4–July 31, 1977. See also Edgar Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, exh. cat. (London: Merrell, 2002), 115. Munhall characterized the execution of the Kansas City painting as “feeble” and never altered his view that it was a copy; see notes from a conversation between Ian Kennedy, NAMA, and Edgar Munhall, July 30, 2009, NAMA curatorial files. Subsequent scholars generally deferred to his opinion, and, as a result, the status of the Nelson-Atkins Nursemaids became uncertain; the museum reflected this uncertainty by designating the picture as “attributed to Greuze.”13For example, Colin B. Bailey, Patriotic Taste: Collecting Modern Art in Pre-Revolutionary Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 211 (”whereabouts unknown, copy in Kansas City, Nelson-Atkins Museum“); Emma Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 271n11 (“it is unlikely to be the work exhibited in 1765; it is probably a copy from another hand”).

Yet there are reasons to reconsider the painting and to accept it as Greuze’s original exhibited at the Salon of 1765.14More recently, Yuriko Jackall and Joseph Baillio have both supported the attribution to Greuze; personal communication with the author, July 2018. The argument can be made on several grounds. To start, the Kansas City Nursemaids is by far the best of the known versions of the composition, the only one qualitatively equal to the artist’s style of painting in the mid-1760s. Greuze was a frequently copied artist, even in his own lifetime; we know, for example, that his student Louis Joseph Donvé (1760–1802) exhibited a copy of The Nursemaids at the Salon in Lille in 1785.15“33. Tableau d’après M. Greuze, représentant les Sevreuses. D’un pied neuf pouces de largeur, sur un pied cinq pouces de hauteur” (approx. 18 x 22 1/3 in.). Donvé spent most of his career in Lille, but he was registered at the Royal Academy in Paris as a student of Greuze between February 5, 1781, and March 1785; the 1785 Lille Salon opened on August 30 of that year. See Gaëtane Maës, Les Salons de Lille de l’Ancien Régime à la Restauration (1773–1820) (Dijon: L’échelle de Jacob, 2004), 228, 463. I am grateful to Yuriko Jackall for bringing this information to my attention. This copy is untraced, but several others have come to light in recent years. The best of these, which emerged in France in 2013, appears to be an early copy of some quality, perhaps made in the eighteenth century (Fig. 2).16After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, oil on canvas, 12 5/8 x 15 3/4 in. (32 x 40 cm), private collection. Edgar Munhall to Richard Rand, September 9, 2013, copy in NAMA curatorial file; this version is too small to be identified with the copy by Donvé (see note 15 above). It is roughly the same size as the Nelson-Atkins painting and, tellingly, shows the extended area of the floor with the objects at the lower edge that appears in the engraving, but stylistically it bears little relationship to Greuze’s manner of painting. A far inferior copy, recorded in Germany in 1999, is larger in size and shows the composition in reverse, indicating that the copyist was working from the reproductive engraving.17As relayed to the author from Edgar Munhall. Its size is 19 15/16 x 23 5/8 in. (49 x 60 cm). Another, also in reverse and even less convincing, sold at an auction in Nantes in 2015 as a copy made in the nineteenth century.18“École XIXème s[iècle] d’après J-B Greuze,” Les Sevreuses, oil on canvas, 20 7/8 x 26 3/8 in. (53 x 67 cm), reproduced in Belle Vente Mobilière: Tableaux dont Moret Henry, Guerin Ernest; Art d’Asie dont un ensemble de Tanka, Boudha Maravijaya en Bronze 14e Siècle, Porcelaine Chine; Sculpture, Objets d’Art, Mobilier XVII, XIX, XXE Siècle (La Baule, France: Salorges Enchères, August 12, 2015), no. 55, https://www.encheres-nantes-labaule.com/vente-aux-encheres/22-belle-ventes-mobiliere/11541-ecole-xixeme-s-d-apres-j-b-greuze-les-sevreuses-huile-sur-toile-53-x-67-cm. No doubt others will surface over time. Of course, Greuze’s original may also still be awaiting rediscovery, but the painting technique and materials of the Nelson-Atkins picture are typical of eighteenth-century French practice and consistent with the work of Greuze. Moreover, while early copies were sometimes confused with originals even in Greuze’s lifetime, it is significant that the provenance of the Kansas City Nursemaids can be definitively traced to 1840, and very likely to 1785, and that the picture was long esteemed by early connoisseurs.19A possible exception was when the painting appeared at the Paris sale of the Berthault collection in 1840; the expert writing in the auction catalogue noted that “this picture has always been considered by M. Berthault as the original,” a backhanded compliment that might imply a modicum of doubt. “Ce tableau a toujours été considéré par M. Berthault comme original”; Une Belle Collection de Tableaux Anciens et Modernes, Principalement des Ecoles Hollandaise, Flamande et Française, Miniatures, Aquarelles et Dessins De nos plus célèbres Artistes modernes, Objets de Curiosités, tels que Meubles en marqueterie, écaille et bois de rose; Bronzes dorés et non dorés, Porcelaines d’ancien Sèvres, de Chine, du Japon et de Saxe; Pendules, Ivoires et Bois sculptés, Tabatières, Boîtes et Bas-Reliefs en argent repoussé et ciselé; Objets divers en pierre dure, Bustes en marbre, Vitraux anciens et Venise, Emaux de Limoges, Terres de Bernard Palissy et Faënza, Collection considérable d’Histoire Naurelle [sic], composée d’une suite de Coquilles marines, fluviales et terrestres; Oiseaux, Papillons indigènes et exotiques, Scarabés Reptiles, Minéraux, etc., dont la vente, Après le décès de M. Berthault, ancien Avoué (Paris: Genevoix et Théret, 1840), lot 40, p. 12.

However compromised the current state of the picture may now be, it still exhibits the picturesque qualities that caught the attention of the Salon critics: “Here we recognize the ingenious naïveté of the author,” wrote the critic Charles Joseph Mathon de la Cour. “This painter sees nature as an artist should see it, that is to say, in love, with eyes that miss nothing and embellish everything.”21“On y reconnaît la naïveté ingénieuse de l’Auteur. Ce Peintre voit la nature comme un Artiste doit la voir, c’est-à-dire, en Amant, avec des yeux à qui rien n’échappe, & qui embellissent tout”; Troisième Lettre, à Monsieur **, Sur les Peintures, les Sculptures, et les Gravures, exposées au Sallon [sic] du Louvre en 1765, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Collection Deloynes, vol. 8, no. 110, p. 11, repr., in Charles Joseph Mathon de la Cour, Lettres à Monsieur ** sur les Peintures, les Sculptures et les Gravures, exposées au Sallon [sic] du Louvre en 1765 (Paris: Bauche and D’houry, 1765), 59. For Diderot, who was reminded of works by the Dutch genre painter Adriaen Ostade (1610–85), “the resulting effect rings true. . . . You believe yourself to be in the cottage, nothing suggests otherwise, in either its content or its handling.” Looking at the picture today, however, it is difficult to follow him when he exclaimed that “One can’t paint any more vigorously;” or to agree with him that “as for myself, it’s the picture itself that I’d ask for.”22“On ne peint pas avec plus de vigueur. L’effet en est vrai . . . Vous croyez être dans une chaumière. Rien ne détrompe, ni la chose, ni l’art. On demande que le berceau soit plus piqué de lumière; pour moi, c’est le tableaux que je demande”; Diderot, Salon de 1765, 195, English translation by Goodman, Diderot on Art, 110. But viewers today need to be mindful that the picture no longer presents itself as it must have in 1765.

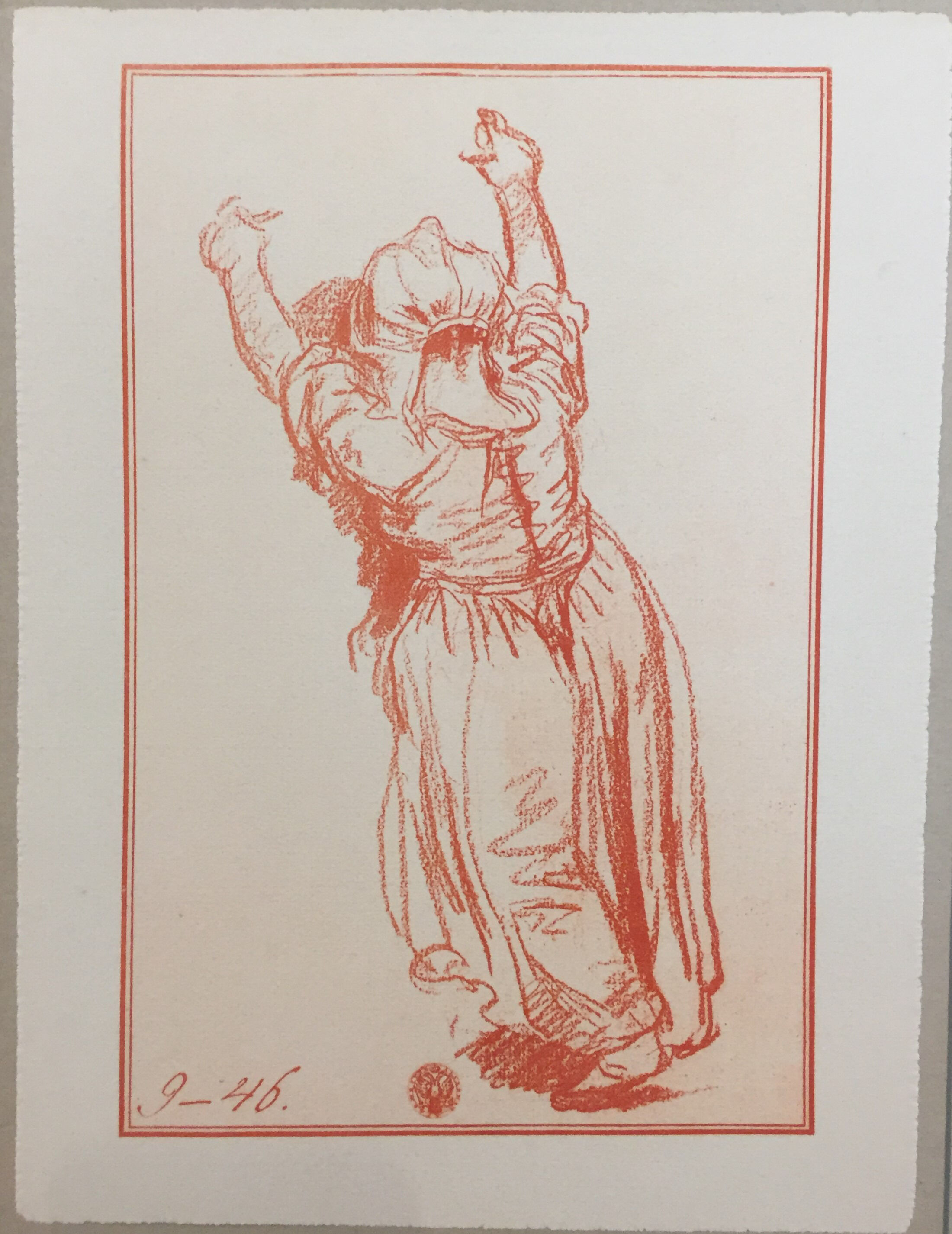

Fig. 4. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Figure of Little Girl, ca. 1765, red chalk on white laid paper, 12 1/8 x 7 15/16 in. (30.7 x 20 cm), State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Fig. 4. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Figure of Little Girl, ca. 1765, red chalk on white laid paper, 12 1/8 x 7 15/16 in. (30.7 x 20 cm), State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Fig. 5. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Study of a Boy Walking, 1765–69, red chalk on cream paper, 11 7/16 x 7 7/16 in. (29.1 x 19 cm), State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, ОР-14978

Fig. 5. Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Study of a Boy Walking, 1765–69, red chalk on cream paper, 11 7/16 x 7 7/16 in. (29.1 x 19 cm), State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, ОР-14978

Whatever function was served by the Nelson-Atkins picture, its subject represents exactly the kind of scene of domestic life that earned Greuze a considerable reputation in the 1750s and 1760s. These genre subjects, bearing such titles as A Father Reading the Bible to his Family, A Marriage Contract, The Spoiled Child, and The Well-Beloved Mother, played into Enlightenment debates regarding family life, motherhood, and childrearing that captured the public’s imagination in the last decades of the eighteenth century. Paintings with these subjects were eagerly sought by prominent collectors: the first recorded owner of The Nursemaids, Laurent Grimod de La Reynière, was a wealthy and well-connected fermier généralfermier général: French for “general farmer.” A private citizen who collects taxes on behalf of the French monarchy.; it later appeared in the sale of works belonging to Jean Dubois (active 1768–89), a goldsmith and jeweler who assembled a celebrated collection.33See Bailey, Patriotic Taste, 211, 225, 252n148, 303n35.

The practice of wet nursing—common across all classes of society, even as it was roundly condemned by such advanced thinkers as Jean Jacques Rousseau—was a theme Greuze explored on several occasions.34The best analysis is Bernadette Fort, “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing in Eighteenth-Century France,” in Anja Müller, ed., Fashioning Childhood in the Eighteenth Century: Age and Identity (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006), 117–34. See also Duncan, “Happy Mothers,” 570–83; and Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment, 271ff. In the Kansas City painting, Greuze depicted the subject with wry humor, evident in its shabby interior setting and the seemingly grouchy nursemaids, yet its warning against the dangers of farming children out to nursemaids would not have been lost on viewers. Munhall, noting that the French word sevrage means weaning, more specifically identified the women as “dry nurses,” who introduce broth and milk soup (bouillie) into the child’s diet as they transition from breastfeeding.35Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, 115–16; see also Fort, “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing,” 119. This comports with the actions represented in the painting, as the women are not shown actually nursing the children, and a bowl and spoon are visible on the table in the right background. In expressing a transitional moment in childhood, Greuze was typically intent—at least as revealed by the Kansas City picture and the reproductive engraving—in bringing meaningful specificity to the expressions and actions of the figures. Bernadette Fort recognized that the activities of the older children conform to traditional gender roles: “domination” for the two boys, one of whom controls the dog while the other places a bird in a cage, and “domesticity” for the girls, one of whom sits quietly holding a doll in her lap (anticipating the action of the central nursemaid) while the other turns to the second nurse for assistance.36Fort, “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing,” 120–21.

Normally, the critics reveled in such meaningful nuances in Greuze’s paintings, yet the few writers who discussed the painting focused more on its aesthetic qualities than its broader meanings. Diderot offered a telling exception, informing his readers that Greuze’s picture was hung at the 1765 Salon beneath Alexandre Roslin’s group portrait of the La Rochefoucauld family (private collection, France), a painting that was roundly criticized by Salon reviewers: “It’s as though he’d written below one of these paintings, ‘Example of Discord,’ and below the other, ‘Example of Harmony.’”37Diderot, Salon de 1765, 194. The “he” referenced was the artist Jean Siméon Chardin (1699–1779) who served as Salon tapissier (curator responsible for the installation) from 1761 to 1773. Diderot further related that Roslin competed with Greuze for the commission, ultimately winning it through the intervention of the marquis de Marigny. The unsatisfactory result (in the opinion of Diderot) prompted the critic to describe in detail what Greuze would have painted; Naigeon, ed., Œuvres de Denis Diderot, 131–37. For Gabriel de Saint-Aubin’s sketch of Roslin’s portrait, see Gunnar W. Lundberg, Roslin: liv och verk (Malmö: AB Allhems Förlag, 1957), no. 209, pp. 1:87–89; 3:41–42. For criticism of Roslin’s portrait, see Emma Barker, “ ‘No Picture More Charming’: The Family Portrait in Eighteenth-Century France,” Art History, 40, no. 3 (2017): 535–36, http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12247. In Gabriel de Saint-Aubin’s celebrated drawing of the Salon installation in 1765 (Musée du Louvre, Paris), one can make out several small, framed pictures hanging directly beneath Roslin’s large painting in the middle of the left wall, one of which must be Greuze’s Sevreuses. Unfortunately, Saint-Aubin did not provide sufficient detail to identify the picture precisely.

Notes

-

Explication des Peintures, Sculptures, et Gravures, de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale, exh. cat. (Paris: Jean-Th. Herissant, 1765), nos. 110–25.

-

“En allant de la droite à la gauche, trois tonneaux debout sur une même ligne; une table; sur cette table une écuelle, un poëlon, un chaudron, et autres ustensiles de ménage. Sur le plan antérieur, un enfant qui conduit un chien avec une corde; à cet enfant tourne le dos une paysanne, sur le giron de laquelle une petite fille est endormie. Plus vers le fond, un assez grand enfant qui tient un oiseau, on voit un tambour à ses pieds, et la cage de l’oiseau attachée au mur. Ensuite une autre femme assise et grouppée [sic] avec trois petits enfans [sic]; derrière elle un berceau; sur le pied du berceau un chaton; à terre, au-dessous, un coffre, un oreiller, des bâtons de coteret [sic] et autres agrès de chaumières et de sevreuses”; Denis Diderot, Salon de 1765, 1765; repr., in Jacques-André Naigeon, ed., Œuvres de Denis Diderot (Paris: Deterville, 1799–1800), no. 121, pp. 13:194–95; translation by John Goodman, Diderot on Art (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), 1:109–10.

-

Yves Bruand and Michèle Hébert, Inventaire du Fonds Français: Graveurs du XVIIIe Siècle (Paris: Bibilothèque nationale, 1970), no. 15, p. 11:609.

-

Conservation records indicate that the painting has been relined, and a radiograph reveals the location of a fill along the bottom edge, ranging between 1/8 and 3/8 inch in height, that extends to the edge of the picture plane across the length of the bottom edge. See the accompanying technical entry by Mary Schafer.

-

Harold Woodbury Parsons to J. C. Nichols, NAMA trustee, July 8, 1930, NAMA curatorial files.

-

Catalogue of Pictures by Old Masters and some Water Colour Drawings, The Property of The Hon. Mrs. Yorke, deceased, Late of 17 Curzon Street, W. 1, and Hamble Cliff, Netley, Southampton, Most of the Old Pictures were Inherited from her Father, the Late Sir Anthony Rothschild, Bt.; Also Choice Pictures of the French School, the Property of the Rt. Hon. Viscountess Harcourt and Old Pictures and Drawings From Other Sources (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, May 6, 1927), lot 28, p. 7.

-

John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters; In which is included a short Biographical Notice of the Artists, with a Copious Description of Their Principal Pictures; A Statement of the Prices at which such Pictures have been Sold at Public Sales on the Continent and in England; A Reference to the Galleries and Private Collections, in which a Large Portion are at Present; and the Names of the Artists by whom they have been Engraved to which is added, A Brief Notice of the Scholars and Imitators of the Great Masters of the Above Schools (London: Smith and Son, 1837), no. 39, p. 8:411.

-

John Smith, Supplement to the Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters; In which is included a short Biographical Notice of the Artists, with a Copious Description of Nearly The Whole of Their Pictures; A Statement of the Prices at which Such Pictures Have Been Sold at Public Sales on the Continent and in England; A Reference to the Galleries and Private Collections, in which a Large Portion are at Present; And the Names of the Artists by whom They Have Been Engraved to which is added, A Brief Notice of the Scholars and Imitators of the Great Masters of the Above Schools (London: Messrs. Smith, 1842), no. 10, p. 9:812

-

Exhibition of the Works of the Old Masters, Associated with A Collection from the Works of Charles Robert Leslie, R.A., and Clarkson Stanfield, R.A., exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1870), no. 133, p. 14.

-

J[ean] Martin and Ch[arles] Masson, Le Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint et Dessiné de Jean-Baptiste Greuze, in Camille Mauclair, Jean-Baptiste Greuze (Paris: H. Piazza, [1905]), no. 207, p. 16.

-

Anita Brookner, Greuze: The Rise and Fall of an Eighteenth-Century Phenomenon (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1972), 64, 106; Carol Duncan, “Happy Mothers and Other New Ideas in French Art,” Art Bulletin 55, no. 4 (December 1973): 576–77.

-

Jean Baptiste Greuze, 1725–1805, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, December 1, 1976–January 23, 1977; The California Palace of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco, March 5–May 1, 1977; the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Dijon, June 4–July 31, 1977. See also Edgar Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, exh. cat. (London: Merrell, 2002), 115. Munhall characterized the execution of the Kansas City painting as “feeble” and never altered his view that it was a copy; see notes from a conversation between Ian Kennedy, NAMA, and Edgar Munhall, July 30, 2009, NAMA curatorial files.

-

For example, Colin B. Bailey, Patriotic Taste: Collecting Modern Art in Pre-Revolutionary Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 211 (“whereabouts unknown, copy in Kansas City, Nelson-Atkins Museum”); Emma Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 271n11 (“it is unlikely to be the work exhibited in 1765; it is probably a copy from another hand”).

-

More recently, Yuriko Jackall and Joseph Baillio have both supported the attribution to Greuze; personal communication with the author, July 2018.

-

“33. Tableau d’après M. Greuze, représentant les Sevreuses. D’un pied neuf pouces de largeur, sur un pied cinq pouces de hauteur” (approx. 18 x 22 1/3 in. or 45.7 x 56.7 cm). Donvé spent most of his career in Lille, but he was registered at the Royal Academy in Paris as a student of Greuze between February 5, 1781, and March 1785; the 1785 Lille Salon opened on August 30 of that year. See Gaëtane Maës, Les Salons de Lille de l’Ancien Régime à la Restauration (1773–1820) (Dijon: L’échelle de Jacob, 2004), 228, 463. I am grateful to Yuriko Jackall for bringing this information to my attention.

-

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, oil on canvas, 12 5/8 x 15 3/4 in. (32 x 40 cm), private collection. Edgar Munhall to Richard Rand, September 9, 2013, copy in NAMA curatorial files; this version is too small to be identified with the copy by Donvé (see note 15 above).

-

As relayed to the author from Edgar Munhall. Its size is 19 15/16 x 23 5/8 in. (49 x 60 cm).

-

“École XIXème s[iècle] d’après J-B Greuze,” Les Sevreuses, oil on canvas, 20 7/8 x 26 3/8 in. (53 x 67 cm), reproduced in Belle Vente Mobilière: Tableaux dont Moret Henry, Guerin Ernest; Art d’Asie dont un ensemble de Tanka, Boudha Maravijaya en Bronze 14e Siècle, Porcelaine Chine; Sculpture, Objets d’Art, Mobilier XVII, XIX, XXE Siècle (La Baule, France: Salorges Enchères, August 12, 2015), no. 55, http://www.encheres-nantes-labaule.com/vente-aux-encheres/22-belle-ventes-mobiliere/11541-ecole-xixeme-s-d-apres-j-b-greuze-les-sevreuses-huile-sur-toile-53-x-67-cm.

-

A possible exception was when the painting appeared at the Paris sale of the Berthault collection in 1840; the expert writing in the auction catalogue noted that “this picture has always been considered by M. Berthault as the original,” a backhanded compliment that might imply a modicum of doubt. “Ce tableau a toujours été considéré par M. Berthault comme original”; Une Belle Collection de Tableaux Anciens et Modernes, Principalement des Ecoles Hollandaise, Flamande et Française, Miniatures, Aquarelles et Dessins De nos plus célèbres Artistes modernes, Objets de Curiosités, tels que Meubles en marqueterie, écaille et bois de rose; Bronzes dorés et non dorés, Porcelaines d’ancien Sèvres, de Chine, du Japon et de Saxe; Pendules, Ivoires et Bois sculptés, Tabatières, Boîtes et Bas-Reliefs en argent repoussé et ciselé; Objets divers en pierre dure, Bustes en marbre, Vitraux anciens et Venise, Emaux de Limoges, Terres de Bernard Palissy et Faënza, Collection considérable d’Histoire Naurelle [sic], composée d’une suite de Coquilles marines, fluviales et terrestres; Oiseaux, Papillons indigènes et exotiques, Scarabés Reptiles, Minéraux, etc., dont la vente, Après le décès de M. Berthault, ancien Avoué (Paris: Genevoix et Théret, 1840), lot 40, p. 12.

-

See accompanying technical entry by Schafer.

-

“On y reconnaît la naïveté ingénieuse de l’Auteur. Ce Peintre voit la nature comme un Artiste doit la voir, c’est-à-dire, en Amant, avec des yeux à qui rien n’échappe, & qui embellissent tout”; Troisième Lettre, à Monsieur **, Sur les Peintures, les Sculptures, et les Gravures, exposées au Sallon [sic] du Louvre en 1765, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Collection Deloynes, vol. 8, no. 110, p. 11, repr., in Charles Joseph Mathon de la Cour, Lettres à Monsieur ** sur les Peintures, les Sculptures et les Gravures, exposées au Sallon [sic] du Louvre en 1765 (Paris: Bauche and D’houry, 1765), 59.

-

“On ne peint pas avec plus de vigueur. L’effet en est vrai . . . Vous croyez être dans une chaumière. Rien ne détrompe, ni la chose, ni l’art. On demande que le berceau soit plus piqué de lumière; pour moi, c’est le tableaux que je demande”; Diderot, Salon de 1765, 195, English translation by Goodman, Diderot on Art, 110.

-

“Petit Tableau,” and “Les figures de ce Tableau sont très-petites”; Troisième Lettre, à Monsieur **, 10–11.

-

For example, Les Œufs Cassés (Salon of 1757; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; 73 x 94 cm); L’Accordée de Village (Salon of 1761; Musée du Louvre, Paris; 92 x 117 cm); Filial Piety (Salon of 1763; Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg; 115 x 146 cm).

-

The drawings in the collection of the Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, are all in red chalk on white paper and are generally 30 x 20 cm to 38 x 30 cm in size. They are studies for the girl reaching up to the nursemaid at the left; the little girl seated with a doll in her lap; the boy holding a bird in his upraised hand; the nursemaid cradling a child at right; and the boy leading the dog. See François Monod and Louis Hautecoeur, Les Dessins de Greuze conservés à l’Académie des Beaux-Arts de Saint-Pétersbourg (Paris: Éditions Albert Morancé, 1922), nos. 30, 33, 36, 40, 64, pp. 11, 15, 25–27, 30, 47. See Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, nos. 34–35.

-

Diderot, Salon de 1765, 194. For the other sketches, see Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, nos. 43, 48–49.

-

“On ne peu pas peint avec plus de vigeur” (Diderot, Salon de 1765, 195).

-

The dimensions of the Nelson-Atkins painting approximate those recorded for Les Sevreuses that sold at auction in 1785 and 1831; see Le Brun, Catalogue d’une Belle Collection de Tableaux des Écoles Flamande, Hollandoise [sic], Allemande et Françoise (Paris: Le Brun et Julliot, 1785), lot 95, p. 45: “Hauteur 12 pouces, largeur 15”; Pierre Roux, Catalogue d’une Précieuse et Riche Collection de Tableaux Provenant de l’Étranger, Après le Décès de M. Bondon, des Trois Écoles Anciennes et Modernes (Paris: Coutellier, Roux, et Le Concierge de la galerie, 1831), lot 81, p. 38: “T. l. 14 p., h. 11 p.”

-

For the Currier painting, see Edgar Munhall, “The First Lessons in Love by Jean-Baptiste Greuze,” Currier Gallery of Art Bulletin (1977): 3–13. The oil sketch served as the model for the engraving by Nicolas Joseph Voyez.

-

Such copy drawings exist for the prints made after at least three of Greuze’s paintings: The Spoiled Child (Salon of 1765), The Well-Beloved Mother (1769), and The Father’s Curse: the Punished Son (Salon of 1777); see Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, nos. 33, 70, and 82. A possible exception is a painted replica of the Getty Laundress in the Harvard University Art Museums undoubtedly by Greuze himself and nearly matching the quality of the prime version. Colin B. Bailey has suggested that this replica may have been painted as a guide for Jean-Claude Danzel’s engraving of 1765; Bailey, Jean-Baptiste Greuze: The Laundress (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Trust, 2000), 20–22. Greuze’s red chalk drawing for the central woman and child in The Nursemaids (Saint Petersburg, Hermitage Museum) is in reverse orientation (it is not a counterproof), which may indicate that it was made as part of the engraving process; see Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, 115. However, it is difficult to see how such a rough, sketchy drawing would benefit the engraver.

-

The full inscription reads: “Les Sevreuses. Gravées d’après le Tableau Original de même grandeur, de Jean Baptiste Greuze Peintre du Roy. Tiré du Cabinet de Monsieur de la Reyniere; Commencé par Mr. Tilliard, et fini par Pierre Charles Ingouf en 1769.”

-

Bruand and Hébert, Inventaire du fonds français, no. 15, p. 609.

-

See Bailey, Patriotic Taste, 211, 225, 252n148, 303n35.

-

The best analysis is Bernadette Fort, “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing in Eighteenth-Century France,” in Anja Müller, ed., Fashioning Childhood in the Eighteenth Century: Age and Identity (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006), 117–34. See also Duncan, “Happy Mothers,” 570–83; and Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment, 271ff.

-

Munhall, Greuze the Draftsman, 115–16; see also Fort, “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing,” 119.

-

Fort, “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing,” 120–21.

-

Diderot, Salon de 1765, 194. The “he” referenced was the artist Jean Siméon Chardin (1699–1779) who served as Salon tapissier (curator responsible for the installation) from 1761 to 1773. Diderot further related that Roslin competed with Greuze for the commission, ultimately winning it through the intervention of the marquis de Marigny. The unsatisfactory result (in the opinion of Diderot) prompted the critic to describe in detail what Greuze would have painted; Naigeon, ed., Œuvres de Denis Diderot, 131–37. For Gabriel de Saint-Aubin’s sketch of Roslin’s portrait, see Gunnar W. Lundberg, Roslin: liv och verk (Malmö: AB Allhems Förlag, 1957), no. 209, pp. 1:87–89; 3:41–42. For criticism of Roslin’s portrait, see Emma Barker, “ ‘No Picture More Charming’: The Family Portrait in Eighteenth-Century France,” Art History, 40, no. 3 (2017): 535–36, http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12247. In Gabriel de Saint-Aubin’s celebrated drawing of the Salon installation in 1765 (Musée du Louvre, Paris), one can make out several small, framed pictures hanging directly beneath Roslin’s large painting in the middle of the left wall, one of which must be Greuze’s Sevreuses. Unfortunately, Saint-Aubin did not provide sufficient detail to identify the picture precisely.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Mary Schafer, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.2088.

MLA:

Schafer, Mary. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.2088.

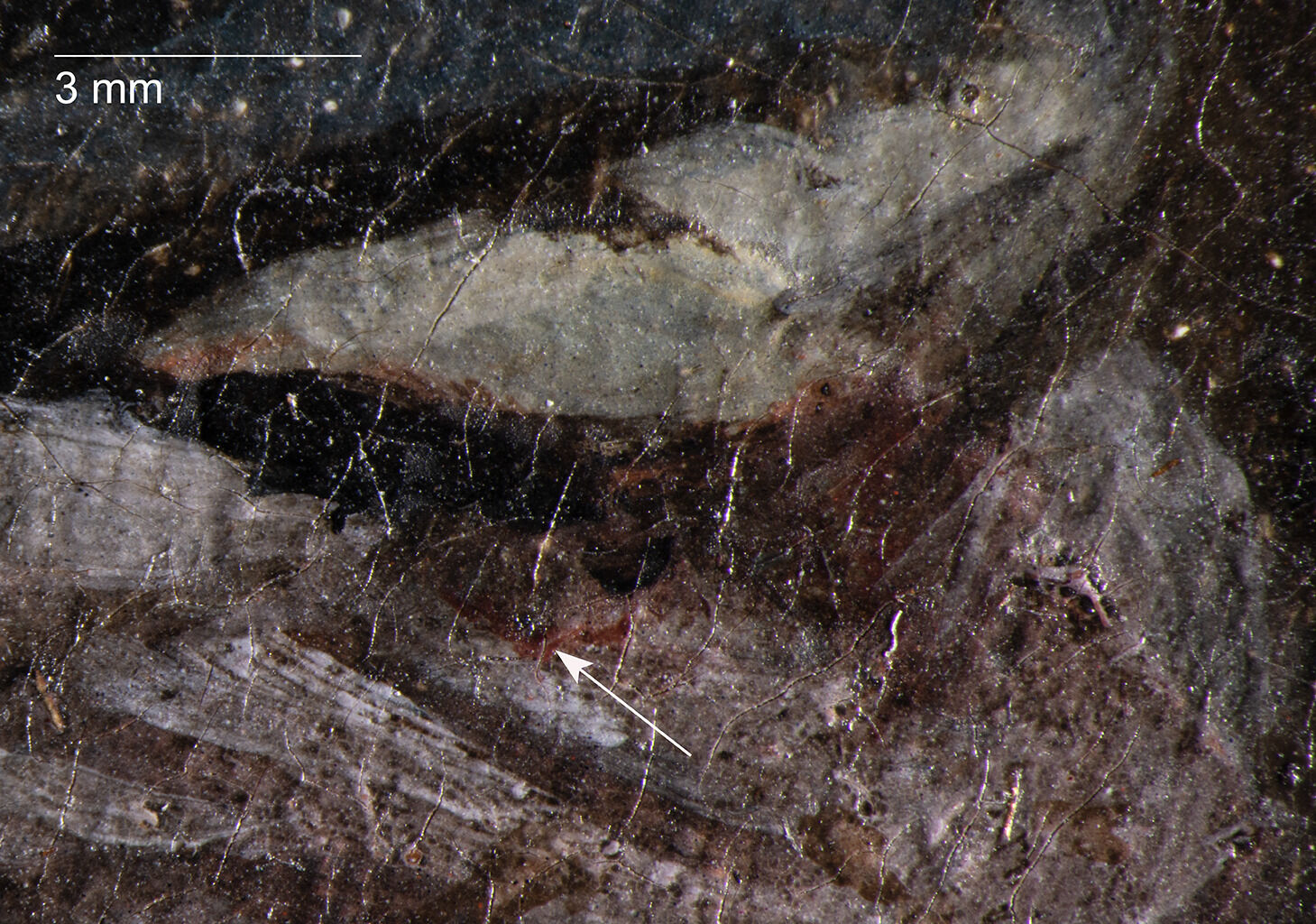

The Nursemaids was acquired by the Nelson-Atkins in 1931 as an autograph work by Jean-Baptiste Greuze, and its authenticity was first questioned in 1979; up until recently, many Greuze specialists referred to the painting as a copy of a lost original. In his accompanying catalogue essay, Richard Rand summarizes the provenance and recorded dimensions of the small-scale canvas and identifies select passages that align with Greuze in terms of quality and style, in spite of the compromised paint surface from past cleaning. Technical study of The Nursemaids with transmitted infrared (IR) photographytransmitted infrared (IR) photography: An examination technique whereby the light source is placed on one side of the artwork while an electronic infrared imager or IR-modified digital camera placed on the opposite side captures the IR that is transmitted. This form of IR photography can be used to detect characteristics of the artist’s paint application, underlying compositions, artist changes, or inscriptions now covered by a lining canvas. and raking illuminationraking light: An examination technique in which light is placed at a shallow angle from one direction to reveal the surface topography. has revealed several artist changes that are significant for any painting whose status has been questioned.

Fig. 7. Details of the objects on the tabletop in the right edge of The Nursemaids (ca. 1765). On the left, normal illumination detail. On the right, a transmitted infrared digital photograph that reveals the outlines of an earlier shape, possibly a cloth.

Fig. 7. Details of the objects on the tabletop in the right edge of The Nursemaids (ca. 1765). On the left, normal illumination detail. On the right, a transmitted infrared digital photograph that reveals the outlines of an earlier shape, possibly a cloth.

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the sleeping child with raking illumination, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765). Thick underlying paint textures are present at the infant’s knee and extend toward the caregiver’s forearm.

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the sleeping child with raking illumination, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765). Thick underlying paint textures are present at the infant’s knee and extend toward the caregiver’s forearm.

Fig. 9. Reflected infrared digital photograph of the crib on the left side of The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 9. Reflected infrared digital photograph of the crib on the left side of The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 10. Stretcher reverse of The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 10. Stretcher reverse of The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the pink-brown wash that lies beneath the left child’s arm, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 11. Photomicrograph of the pink-brown wash that lies beneath the left child’s arm, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the exposed brown wash between the windowpanes, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 12. Photomicrograph of the exposed brown wash between the windowpanes, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

The brightest areas of fabric were constructed with lively strokes of

thick white paint (Fig. 13), while dark glazes deepen areas of

shadows. In the construction of the right female’s dress and the right

boy’s pants, thickly painted highlights establish the drape and fold of

the fabric beneath an overlying violet glaze (Fig. 14).6While the materials of the Nelson-Atkins painting have not been analyzed, Greuze’s writings describe pigment mixtures for rendering violet and yellow drapery: “For violet draperies / White lake, burnt ‘cendre,’ d’angleterre, ultramarine for the lights / For the shadows burnt carmine, Prussian blue.” See “Undated ‘Liste de pigments manuscrite par Greuze,’” Fondation Custodia, Paris, invoice no. i9069a, translated and cited in Yuriko Jackall, Barbara H. Berrie, John Delaney, and Michael Swicklik, “Greuze’s Greens: Ephemeral Colours, Classical Ambitions,” Burlington Magazine 165, no. 1440 (March 2023): 279. A

glimpse of transparent magenta is evident on the boy’s pants

(Fig. 15), and a pink UV-induced visible fluorescenceultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. on the woman’s purple sleeve may indicate a red lake.7Helmut Schweppe and John Winter, “Madder and Alizarin,” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, ed. Elisabeth West FitzHugh (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1997), 3:124. Although no

analysis has been conducted on The Nursemaids, technical study of

other Greuze paintings has confirmed significant color changes resulting

from the artist’s use of fugitive red and yellow lakes that disappeared

after exposure to light.8See David Saunders and Jo Kirby, “Light-Induced Colour Changes in Red and Yellow Lake Pigments,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 15 (1994): 81; Humphrey Wine, The Eighteenth Century French Paintings, 255; and Jackall, Berrie, Delaney, and Swicklik, “Greuze’s Greens,” 268–79.

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph with raking illumination, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765), showing the painterly brushwork of the woman’s skirt

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph with raking illumination, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765), showing the painterly brushwork of the woman’s skirt

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the thick white highlights, overlying glaze, and dark semitransparent shadows of the woman’s blouse, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of the thick white highlights, overlying glaze, and dark semitransparent shadows of the woman’s blouse, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of transparent magenta on the right boy’s pants, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 15. Photomicrograph of transparent magenta on the right boy’s pants, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the right woman, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765), underscoring the deleterious effects of overcleaning on Greuze’s thin paint layers and delicate scumbles

Fig. 16. Photomicrograph of the right woman, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765), underscoring the deleterious effects of overcleaning on Greuze’s thin paint layers and delicate scumbles

Fig. 17. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Fig. 17. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, The Nursemaids (ca. 1765)

Notes

-

See film-based x-radiograph, no. 234, NAMA conservation file, 31-61.

-

For an overview of the painting’s provenance history and recorded dimensions, see the accompanying catalogue entry by Richard Rand.

-

Although double grounds have been identified in many works by Greuze, the white or off-white ground described here is based on limited visual observation without analysis. See Humphrey Wine, The Eighteenth Century French Paintings (London: National Gallery, 2018), 221, 225, 229.

-

No clear underdrawing was identified when the painting was examined with the stereomicroscope. Although finely painted lines at the girl’s wrist in Figure 11 suggest a preliminary sketch, these reinforcing strokes lie on top of the gray sleeve. However, transmitted IR photography suggests the use of fine paint strokes to mark compositional elements.

-

James Thompson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 47, no. 3 (1989): 10–12.

-

While the materials of the Nelson-Atkins painting have not been analyzed, Greuze’s writings describe pigment mixtures for rendering violet and yellow drapery: “For violet draperies / White lake, burnt ‘cendre,’ d’

angleterre, ultramarine for the lights / For the shadows burnt carmine, Prussian blue.” See “Undated ‘Liste de pigments manuscrite par Greuze,’” Fondation Custodia, Paris, invoice no. i9069a, translated and cited in Yuriko Jackall, Barbara H. Berrie, John Delaney, and Michael Swicklik, “Greuze’s Greens: Ephemeral Colours, Classical Ambitions,” Burlington Magazine 165, no. 1440 (March 2023): 279. -

Helmut Schweppe and John Winter, “Madder and Alizarin,” in Artists’ Pigments: A Handbook of their History and Characteristics, ed. Elisabeth West FitzHugh (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1997), 3:124.

-

See David Saunders and Jo Kirby, “Light-Induced Colour Changes in Red and Yellow Lake Pigments,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 15 (1994): 81; Humphrey Wine, The Eighteenth Century French Paintings, 255; and Jackall, Berrie, Delaney, and Swicklik, “Greuze’s Greens,” 268–79.

-

Scott Heffley, September 14, 1992, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 31-61.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

Laurent Grimod de la Reynière (1734–93), Paris, by October 30, 1769 [1];

Jean Dubois (active 1768–89), by December 20, 1785 [2];

Purchased from his sale, Une belle collection de tableaux des écoles flamande, hollandoise, allemande, et françoise, par M. Le Brun, garde des tableaux du mgr. Comte d’Artois, ce catalogue est suivi de celui des marbres, figures de bronze, et bronzes dorés, porcelaines du Japon, de la Chine, laques, bijoux, meubles de Boule, et autres objets de curiosité, par Ph. F. Julliot, Hôtel de Bullion, Paris, December 20, 1785, no. 95, as L’intérieur d’une Maison de paysan, où l’on voit une famille au nombre de sept personnes, femmes et enfans, parmi lesquels on distingue principalement et sur le devant une jeune femme assise, tenant dans ses bras un enfant à la mammelle, et près d’elle un jeune garçon debout tenant un chien en lesse, by Louis François Saubert, 1785–at least February 13, 1793 [3];

Bondon (probably Louis François Bondon, 1767–1825, Darmstadt, Germany), by January 12, 1825 [4];

His posthumous sale, Une Précieuse et Riche Collection de Tableaux Provenant de l’Étranger, Après le Décès de M. Bondon, des Trois Écoles Anciennes et Modernes, la salle Lebrun, rue de Cléry, no. 21, Paris, June 7–8, 1831, no. 81, as les Sèvreuses;

Berthault (possibly Nicolas Gilles Berthault, ca. 1751–ca. 1840, Versailles), by 1840 [5];

His posthumous sale, Une Belle Collection de Tableaux Anciens et Modernes, Principalement des Ecoles Hollandaise, Flamande, et Française, Miniatures, Aquarelles et Dessins De nos plus célèbres Artistes modernes, Objets de Curiosités, tels que Meubles en marqueterie, écaille et bois de rose; Bronzes dorés et non dorés, Porcelaines d’ancien Sèvres, de Chine, du Japon et de Saxe; Pendules, Ivoires et Bois sculptés, Tabatières, Boîtes et Bas-Reliefs en argent repoussé et ciselé; Objets divers en pierre dure, Bustes en marbre, Vitraux anciens et Venise, Emaux de Limoges, Terres de Bernard Palissy et Faënza, Collection considérable d’Histoire Naturelle, composée d’une suite de Coquilles marines, fluviales et terrestres; Oiseaux, Papillons indigènes et exotiques, Scarabés Reptiles, Minéraux, etc., dont la vente, Après le décès de M. Berthault, ancien Avoué, Hôtel des Commissaires-Priseurs, Paris, November 23–24, 1840, no. 40, as Les sevreuses;

Sir Anthony Nathan (Billy) de Rothschild, First Baronet (1810–76), London, and Aston Clinton, Buckinghamshire, England, by 1842–January 3, 1876 [6];

Inherited by his daughter, the Hon. Mrs. Eliot Constantine Yorke (née Annie de Rothschild, 1844–1926), London, and Hamble Cliff, Netley, Southampton, by 1876–November 21, 1926 [7];

Purchased from her posthumous sale, Pictures by Old Masters and some Water Colour Drawings, The Property of The Hon. Mrs. Yorke, deceased, Late of 17 Curzon Street, W. 1, and Hamble Cliff, Netley, Southampton, Most of the Old Pictures were Inherited from her Father, the Late Sir Anthony Rothschild, Bt.; Also Choice Pictures of the French School, the Property of the Rt. Hon. Viscountess Harcourt and Old Pictures and Drawings From Other Sources, Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, May 6, 1927, no. 28, as Les Sevreuses, by Thomas Agnew and Sons, Inc., New York, stock no. 6685, 1927–February 10, 1931 [8];

Purchased from Thomas Agnew and Sons, Inc., through Count Antoine Frederic Adolphe Sala and Harold Woodbury Parsons, by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1931 [9].

Notes

[1] See the inscription under the engraving after the painting, “Gravées d’après le Tableau Original de mème grandeur, de Jean Baptiste Greuze Peintre du Roy/ Tiré du cabinet de Monsieur de la Reyniere; Commencé par Mr. Tilliard,/ et fini par Pierre Charles Ingouf en 1769.” Jean-Baptiste Tilliard and P.-C. Ingouf, after Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, 1769, engraving, 12 5/8 x 15 3/4 in. (32 x 40 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, BN, Dc-8-Fol. Reynière must have had the painting by 1769, when the engraving was announced in L’Avant-Coureur, no. 44 (October 30, 1769): 689–90. John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters (London: Smith and Son, 1837), 8:411, says that the painting was “Engraved by P.C. Ingouf, 1769, from a picture then in the cabinet of M. Tilliard.” This is probably an erroneous translation of the engraving inscription.

[2] The collector was possibly Jean Dubois, a jeweler, goldsmith and art dealer, who was received by the guild on August 22, 1781. See Colin B. Bailey, Patriotic Taste: Collecting Modern Art in Pre-Revolutionary Paris (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), 28, 252n148, and Henry Nocq, Le Poinçon de Paris: Répertoire des Maîtres-Orfèvres de la Juridiction de Paris depuis le Moyen-Âge jusqu’à la fin du XVIIIe Siècle (Pairs: H. Floury, 1927), 2:103.

[3] The painting also appears in this sale, where dealer Saubert was both the seller and the buyer: Une Collection de Tableaux des Trois Écoles, Dessins, Estampes montées et en feuilles, Bibliothèques, Secrétaires, Commodes en bois d’Acajou, Bronze, Porcelaine, Bijoux, Montres à répétitions, et autres objets curieux, provenant en partie de l’Etranger (Paris: Lebrun, February 13, 1793), no. 85, as a work after Greuze, Un petit Tableau, d’après ce Maître, représentant les Sevreuses.

[4] The constituent’s name is listed as “Bondon” in the 1831 sales catalogue, but it has also been written as “Bondon père,” “Bonbon père,” or “Boudonpère.” Frits Lugt, Répertoire des Catalogues de Ventes Publiques Intéressant, l’Art ou la Curiosité, vol. 2 (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1953), gives the name as “Bonbon père” and says the constituent died in Germany. Bondon is also cited as “une amateur du Midi de la France” in a May 30–June 1, 1839, sale (Lugt 15471). Louis François Bondon, a likely option for this constituent, was a goldsmith and jeweler who was born in Avignon in the south of France (called the Midi) and died in 1825 in Darmstadt, Germany.

[5] Sometimes the constituent’s name is erroneously written as “Berthaud.” We defer here to the sales catalogue from 1840 for his spelling. This constituent might be Nicolas Gilles Berthault (ca. 1751–ca. 1840), an attorney living in Versailles from 1785 until at least 1824. See marriage bans of Nicolas Gilles Berthault and Catherine Bonté, Registre de la Paroisse de Bièvre, no. 11, dated May 9, 1785. Nicolas Gilles Berthault’s residence in Versailles was documented on May 7, 1824 in Bulletin des lois de la République Française, no. 691 bis (1824): 13.

[6] John Smith, Supplement to the Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters; In which is included a short Biographical Notice of the Artists, with a Copious Description of Nearly The Whole of Their Pictures; A Statement of the Prices at which Such Pictures Have Been Sold at Public Sales on the Continent and in England; A Reference to the Galleries and Private Collections, in which a Large Portion are at Present; And the Names of the Artists by whom They Have Been Engraved to which is added, A Brief Notice of the Scholars and Imitators of the Great Masters of the Above Schools (London: Messrs. Smith, 1842), 9:812.

[7] The painting was possibly inherited by his wife, Louisa (née Montefiore, 1821–1910), Lady de Rothschild, Aston Clinton, Buckinghamshire, England, 1876, but the catalogue of Hon. Mrs. Eliot Constantine Yorke’s (née Annie de Rothschild) posthumous sale in 1927 says “Most of the Old Pictures were Inherited from her Father, the Late Sir Anthony Rothschild, Bt.” in the title. See Catalogue of Pictures by Old Masters and some Water Colour Drawings, The Property of The Hon. Mrs. Yorke, deceased, Late of 17 Curzon Street, W. 1, and Hamble Cliff, Netley, Southampton, Most of the Old Pictures were Inherited from her Father, the Late Sir Anthony Rothschild, Bt.; Also Choice Pictures of the French School, the Property of the Rt. Hon. Viscountess Harcourt and Old Pictures and Drawings From Other Sources (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, May 6, 1927.

[8] The painting was sold from Yorke’s estate by direction of her niece, Hon. Marie Constance (née Adeane, 1862–1934), Lady Mallet. See Yorke’s sales catalogue, page 5. Genealogical research on Lady Mallet conducted by Ann Friedman, NAMA volunteer, fall 2018. For the purchaser, see The National Gallery, London, Thomas Agnew and Sons Ltd. Archive, NGA27/1/1, Picture Stock Books. Also an annotated catalogue from the Art Institute of Chicago for Yorke’s 1927 sale indicates that “Agnew” purchased the painting from the sale. Many newspapers reported that Agnew purchased the painting from the 1927 Yorke sale.

[9] Count Antoine Sala (1876–1946) was an art dealer and the representative of Thomas Agnew and Sons, Inc. in Paris; see René Gimpel, Diary of an Art Dealer (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1966), 255. Harold Woodbury Parsons, art advisor to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in the 1930s, was in discussion with Count Sala about purchasing the painting on behalf of the museum as early as July 8, 1930; see letter from Harold Woodbury Parsons to J. C. Nichols, NAMA trustee, July 8, 1930, NAMA curatorial files. See letter from February 4, 1931, Ernest E. Brown, secretary to Thomas Agnew and Sons, London, which says the painting was “purchased through Count Antoine Sala” (emphasis added; see letter in NAMA curatorial files).

Reproductions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

Jean-Baptiste Tilliard and Pierre Charles Ingouf, after Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, 1769, engraving, image: 12 5/8 x 15 3/4 in. (32 x 40.2 cm), plate: 15 1/16 x 16 5/8 in. (38.3 x 42.2 cm), sheet: 15 13/16 x 20 11/16 in. (40.2 x 52.6 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, BN, Dc-8-Fol.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Figure of a little girl, sitting facing forward, square neckline and wearing a hat, ca. 1765, red chalk on white laid paper, 11 x 8 7/8 in. (28 x 22.5 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Figure of little girl, in cap, laced bodice and long skirt; seen from the back, she raises her arms to the left, ca. 1765, red chalk on white laid paper, 12 1/8 x 7 15/16 in. (30.7 x 20 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Figure of little boy, seen from back and 3/4; his pants are attached to his corset; his right hand holds an object (not drawn), ca. 1765, red chalk on white laid paper, 11 7/16 x 7 1/2 in. (29 x 19.1 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Figure of young boy, standing, facing front; he raises his left arm and advances with a happy air, ca. 1765, red chalk on white laid paper, 15 3/4 x 10 13/16 in. (40 x 27.5 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Woman with a Child on Her Knees, 1765, red chalk on yellowish laid paper, 15 x 10 5/8 in. (38 x 27 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia, ОР-14803.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Study of a Boy Walking, 1765–69, red chalk, 11 7/16 x 7 1/2 in. (29.1 x 19 cm), The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia, ОР-14978.

Jean-Baptiste Greuze, A Cradle, ca. 1765, drawing, Hôtel-Dieu-Musée Greuze, Tournus, France.

Known Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

Louis Joseph Donvé (1760–1802), after Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, ca. 1785, oil on canvas, 18 x 22 1/3 in. (45.7 x 56.7 cm), location unknown, cited in Gaëtane Maës, Les Salons de Lille de l’Ancien Régime à la Restauration (1773–1820) (Dijon: L’Échelle de Jacob, 2004), 228, 463.

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, 18th century, oil on panel, 11 1/2 x 14 1/4 in. (29.2 x 10.8 cm), cited in Catalogue de tableaux originaux . . . gouaches et dessins encadrés et en feuilles; nombreuse collection d’estampes Françaises et étrangères . . . du cabinet du Citoyen *** (Paris: Maison de Bullion, September 3–7, 1795), no. 22.

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, oil on canvas, 12 5/8 x 15 3/4 in. (32 x 40 cm), private collection, Saint-Cloud, France.

After Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, oil on canvas, 12 5/8 x 15 in. (32 x 38 cm), cited in Catalogue des Tableaux Anciens, Dessins, Aquarelles, Pastels, Gouaches de l’École Française du XVIIIe Siècle et des Écoles Flamande, Hollandaise, et Italienne, Nombreux cadres en bois doré des XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles, Objets d’art et d’ameublement, anciennes porcelaines de la Chine et du Japon; Orfèvrierie du XVIIIe siècle; Miniatures, objets divers; Relieures Louis XV et Lou XVI; Bronzes, Pendules, Sièges, Glaces, Meubles; Dont la Vente aura lieu à Paris par suite du décès de M. Henri Lacroix (Paris: Hotel Drouot, March 18–23, 1901), 7, 26.

After Jean-Baptiste Tilliard and Pierre Charles Ingouf, after Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, oil on canvas, 19 15/16 x 23 5/8 in. (49 x 60 cm), location unknown.

After Jean-Baptiste Tilliard and Pierre Charles Ingouf, after Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Les Sevreuses, oil on canvas, 20 15/16 x 26 7/16 in. (53 x 67 cm), illustrated in Belle Vente Mobiliere: Tableaux dont Moret Henry, Guerin Ernest; Art d’Asie dont un ensemble de Tanka, Boudha Maravijaya en Bronze 14e Siècle, Porcelaine Chine, Sculpture, Objets d’Art, Mobilier XVII, XIX, XXe Siècle (La Baule, France: Salorges Enchères, August 12, 2015), no. 55, http://www.encheres-nantes-labaule.com/vente-aux-encheres/22-belle-ventes-mobiliere/11541-ecole-xixeme-s-d-apres-j-b-greuze-les-sevreuses-huile-sur-toile-53-x-67-cm.%20.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

Salon de 1765, Salon du Louvre, Paris, hors cat.

Exhibition of the Works of the Old Masters, Associated with A Collection from the Works of Charles Robert Leslie, R.A., and Clarkson Stanfield, R.A., Royal Academy of Arts, Burlington House, London, January–February 1870, no. 133, as A French Family.

The Century of Mozart, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 15–March 4, 1956, no. 46, The Nursemaids.

Genre, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 5–May 15, 1983, no. 18, The Nursemaids.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Jean-Baptiste Greuze, The Nursemaids, ca. 1765,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2023. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.316.4033.

Denis Diderot, The Salon of 1765 (1765; repr., in Jacques-André Naigeon, ed., Œuvres de Denis Diderot [Paris: Deterville, 1799]), 13:194–95, as Les Sevreuses.

Troisième Lettre, à Monsieur **, Sur les Peintures, les Sculptures, et les Gravures, exposées au Sallon du Louvre en 1765, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Collection Deloynes, vol. 8, nos. 108, 110, pp. 10–11 [repr., in Charles Joseph Mathon de la Cour, Lettres à Monsieur ** sur les Peintures, les Sculptures et les Gravures, exposées au Sallon du Louvre en 1765 (Paris: Bauche and D’houry, 1765), 58–59], as Les Sevreuses.

“Arts: Gravure,” L’Avant-Coureur, no. 44 (October 30, 1769): 689–90.

“Annonces et Avis Divers,” Annonces, Affiches, et Avis Divers, no. 87 (November 9, 1769): 962.

“Gravure,” Mercure de France (December 1769): 199.

“Nouvelles Littéraires,” Journal des Beaux-Arts et des Sciences 1 (February 1770): 380.

Catalogue d’une Belle Collection de Tableaux des Écoles Flamande, Hollandoise, Allemande, et Françoise, par M. Le Brun, Garde des Tableaux du Mgr. Comte d’Artois, Ce Catalogue est suivi de celui des Marbres, Figures de bronze, et bronzes dorés, Porcelaines du Japon, de la Chine, Laques, Bijoux, Meubles de Boule, et autres Objets de curiosité, par Ph. F. Julliot (Paris: Hôtel de Bullion, December 20, 1785), 45, as L’intérieur d’une Maison de paysan, où l’on voit une famille au nombre de sept personnes, femmes et enfans, parmi lesquels on distingue principalement et sur le devant une jeune femme assise, tenant dans ses bras un enfant à la mammelle, et près d’elle un jeune garçon debout tenant un chien en lesse.

Catalogue d’une Collection de Tableaux des Trois Écoles, Dessins, Estampes montées et en feuilles, Bibliothèques, Secrétaires, Commodes en bois d’Acajou, Bronze, Porcelaine, Bijoux, Montres à répétitions, et autres objets curieux, provenant en partie de l’Etranger (Paris: Lebrun, February 13, 1793), 17, as Un petit tableau, d’après ce maître, représentant les Sevreuses.

Denis Diderot, Œuvres Inédites. Le Neveu de Rameau. Voyage de Hollande (Paris: J.L.J. Brière 1821), 413, as Les sevreuses.

Œuvres Complètes de Diderot (Paris: J.L.J. Brière, 1821), 8:268–69, as Les Sevreuses.

Pierre Roux, ed., Catalogue d’une Précieuse et Riche Collection de Tableaux Provenant de l’Étranger, Après le Décès de M. Bondon, des Trois Écoles Anciennes et Modernes (Paris: Coutellier, Roux, et Le Concierge de la galerie, June 7–8, 1831), 38.

John Smith, A Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters; In which is included a short Biographical Notice of the Artists, with a Copious Description of Their Principal Pictures; A Statement of the Prices at which such Pictures have been Sold at Public Sales on the Continent and in England; A Reference to the Galleries and Private Collections, in which a Large Portion are at Present; and the Names of the Artists by whom they have been Engraved to which is added, A Brief Notice of the Scholars and Imitators of the Great Masters of the Above Schools (London: Smith and Son, 1837), 8:411, as Les Sevreuses.

Catalogue d’Une Belle Collection de Tableaux Anciens et Modernes, Principalement des Ecoles Hollandaise, Flamande, et Française, Miniatures, Aquarelles et Dessins De nos plus célèbres Artistes modernes, Objets de Curiosités, tels que Meubles en marqueterie, écaille et bois de rose; Bronzes dorés et non dorés, Porcelaines d’ancien Sèvres, de Chine, du Japon et de Saxe; Pendules, Ivoires et Bois sculptés, Tabatières, Boîtes et Bas-Reliefs en argent repoussé et ciselé; Objets divers en pierre dure, Bustes en marbre, Vitraux anciens et Venise, Emaux de Limoges, Terres de Bernard Palissy et Faënza, Collection considérable d’Histoire Naurelle [sic], composée d’une suite de Coquilles marines, fluviales et terrestres; Oiseaux, Papillons indigènes et exotiques, Scarabés Reptiles, Minéraux, etc., dont la vente, Après le décès de M. Berthault, ancien Avoué (Paris: Genevoix et Théret père, November 23–24, 1840), 11–12, as Les sevreuses.

John Smith, Supplement to the Catalogue Raisonné of the Works of the Most Eminent Dutch, Flemish, and French Painters; In which is included a short Biographical Notice of the Artists, with a Copious Description of Nearly The Whole of Their Pictures; A Statement of the Prices at which Such Pictures Have Been Sold at Public Sales on the Continent and in England; A Reference to the Galleries and Private Collections, in which a Large Portion are at Present; And the Names of the Artists by whom They Have Been Engraved to which is added, A Brief Notice of the Scholars and Imitators of the Great Masters of the Above Schools (London: Messrs. Smith, 1842), 9:812, as The Nursery.

“Works of the Great Masters: Jean-Baptiste Greuze,” Illustrated Magazine of Art 2, no. 8 (1853): 111, as Les Sevreuses.

Gustav Waagen, Treasures of Art in Great Britain: Being an Account of the Chief Collections of Paintings, Drawings, Sculptures, Illuminated MSS., etc., etc. (London: John Murray, 1854), 2:281–82, as The Nursery.

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, “Greuze,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 13 (December 1, 1862): 520, as les Sevreuses.

Jules Renouvier, Histoire De L’Art Pendant La Revolution, Considéré Principalement Dans Les Estampes; Ouvrage Posthume. Suivi D’Une Étude Du Même Sur J.-B. Greuze, Avec Une Notice Biographique Et Une Table Par M. Anatole de Montaiglon (Paris: Vve J. Renouard, 1863), 511, as les Sevreuses.

Théodore Lejeune, Guide Théorique Et Pratique De L’Amateur De Tableaux; Études Sur Les Imitateurs Et Les Copistes Des Maitres De Toutes Les Écoles Dont Les Œuvres Forment La Base Ordinaire Des Galleries (Paris, Vve. Jules Renouard, 1864), 1:281, as Les Sevreuses.

Charles Blanc, Histoire des Peintres de Toutes les Écoles: École Française (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1865), 2:16, as Les Sevreuses.

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, “La Peinture de Greuze,” Revue du XIXe siècle 9 (October 1868): 65, as Sevreuses.

Exhibition of the Works of the Old Masters, Associated with A Collection from the Works of Charles Robert Leslie, R.A., and Clarkson Stanfield, R.A., exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1870), 14, as A French Family.

Jules Assezat, ed., Œuvres Complètes De Diderot, Revues Sur Les Éditions Originales, Comprenant Ce Qui A Été Publié À Diverses Époques Et Les Manuscrits Inédits, Conservés À La Bibliothèque de l’Ermitage, Notices, Notes, Table Analytique. Étude sur Diderot et le Mouvement Philosophique Au XVIIIe Siècle (Paris: Garnier frères, 1876), 10:358–59, as Les Sevreuses.

“L’Académie des Arts de Lille,” Mémoires de la Société des Sciences de l’Agriculture et des Arts de Lille et Publications Faits par ses soins 4, no. 3 (1877): 303–04.

P. Martin, “Greuze et Diderot,” Annales de l’Académie de Macon, 2nd ser., vol. 2 (1880): 89n3, as Sevreuses.

Baron Roger Portalis and Henri Beraldi, Les Graveurs du Dix-Huitième Siècle, vol. 2, pt. 2 (Paris: Damascène Morgand et Charles Fatout, 1881), 454.

Maurice Tourneux, ed., Morceaux Choisis de D. Diderot (Paris: Charavay frères, 1881), 201, as Les Sevreuses; autre esquisse.

Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, L’Art du XVIIIme Siècle, 2nd ser. (Paris: G. Charpentier, 1882), 89 [repr., in Edmond and Jules de Goncourt, L’Art du XVIIIe Siècle, ed. Jean-Louis Cabanès (Tusson, Charente, France: Du Lérot, 2007), 1:255, 402n91], as Les Sevreuses.

Denis Diderot, Paradoxe sur le Comédien (Paris: Librairie de la Bibliothèque nationale, 1887), 179–80, as Les Sevreuses.

Ch[arles] Normand, J.-B. Greuze (Paris: L. Allison et Cie, 1892), 50, 109, as Les Sevreuses.

Gustave Bourcard, Dessins, Gouaches, Estampes et Tableaux du Dix-Huitième Siècle; Guide de l’Amateur (Paris: Damascène Morgand, 1893), 259, as Les Sevreuses.

Denis Diderot, Œuvres Choisies de Diderot; Précédées de Sa Vie par Mme de Vandeul et d’une introduction par François Tulou (Paris: Garnier frères, 1901), 2:354, as Les Sevreuses.

Alfred Picard et al., Musée Rétrospectif du Groupe I: Éducation et Enseignement à l’Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1900 à Paris: Rapport du Comité d’Installation, exh. cat. (Saint-Cloud, France: Imprimerie Belin frères, 1901), 44, as Les Sevreuses.

J[ean] Martin and Ch[arles] Masson, Le Catalogue Raisonné de l’Œuvre Peint et Dessiné de Jean-Baptiste Greuze (Paris: H. Piazza, 1905), no. 207, p. 16 [repr., in Camille Mauclair, Jean-Baptiste Greuze (Paris: H. Piazza, 1905)], as Les Sevreuses.

Camille Mauclair, Jean-Baptiste Greuze (Paris: H. Piazza, 1905), 88, as les Sevreuses.

Jean Martin, Œuvre de J.-B. Greuze: Catalogue raisonné, Suivi de la liste des gravures exécutées d’après ses ouvrages (Paris: G. Rapilly, 1908), no. 207, p. 16, as Les Sevreuses.

Étienne Deville, Index du Mercure de France, 1672–1832 (Paris: Jean Schemit, 1910), 104, 115, as Les Sevreuses and erroneously as Les Semeuses.

Hippolyte Mireur, Dictionnaire des Ventes d’Art faites en France et à l’Étranger pendant les XVIIIme et XIXme Siècles (Paris: Maisons d’Éditions d’Œuvres Artistiques, 1911–12), 3:358, 4:5, 7:186, as Les sevreuses.

John Rivers, Greuze and His Models (London: Hutchinson, 1912), 272, as Les Sévreuses [sic].

J. J. Mahéo, “Chroniques de la Semaine: Bibliographie,” Revue Contemporaine, no. 74 (March 23, 1913): 180.

Louis Hautecœur, Greuze (Paris: Librairie Félix Alcan, 1913), 58, as Sevreuses.

Gemälde alter und neuer Meister Handzeichnungen, Aquarelle, Ölstudien aus Freiherrlichem und anderem Besitz (Berlin: Rudolph Lepke’s Kunst-Auctions-Haus, April 30–May 1, 1916), 14.

Georges Giacometti, Le Statuaire Jean-Antoine Houdon et Son Époque (1741–1828) (Paris: Jouve et Cie, 1918), 1:250.

Teekeningen, Gravuren en Etsen, Topographie in Teekening en Prent: Verzamelingen Mr. C. P. Donket, notaris te Hoorn en S. Wigersma te Leeuwarden (Amsterdam: R.W.P. De Vries, March 11–13, 1919), 27.

[Augustin] Cabanès, Mɶurs intimes du Passé, 6th ser. (Paris: Albin Michel, [1920]), 232–33.

Versteigerung einer Sammlung von Ölgemälden, Aquarellen und Kupferstichen, sowie einer kleinen Kunstbibliothek, alter Wiener Privatbesitz nebst einigen Beiträgen (Vienna: C.J. Wawra, May 10, 1922), 34.

François Monod and Louis Hautecœur, Les Dessins de Greuze Conservés à l’Académie des Beaux-Arts de Saint-Pétersbourg (Paris: Éditions Albert Morancé, 1922), 11, 15, 25–27, 30, 47, as Les Sevreuses.

Beatrice A. Waldram, Greuze, 1725–1805 (New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1923), 95, as Les Sevreuses.

François Courboin, Histoire Illustrée de la Gravure en France: De 1600 a [sic] 1800 (Paris: Maurice Le Garrec, 1924), 2:91.

Camille Mauclair, Greuze et Son Temps (Paris: Albin Michel, 1926), 180–81, as Les sevreuses.

A.C.R. Carter, “Forthcoming Auctions: Pallavicini Collections and Others,” Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 50, no. 289 (April 1927): li, as Les Sevreuses.

“The Sale Room: Rothschild Pictures and Furniture,” Times (London), no. 44,553 (April 11, 1927): 11, as Les Sevreuses.

“Christie, Manson, and Woods,” Times (London), no. 44,559 (April 19, 1927): 19, as Les Sevreuses.

A.C.R. Carter, “Forthcoming Auction Sales: The Promise of May,” Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 50, no. 290 (May 1927): xlix, as Les Sevreuses.

Catalogue of Pictures by Old Masters and some Water Colour Drawings, The Property of The Hon. Mrs. Yorke, deceased, Late of 17 Curzon Street, W. 1, and Hamble Cliff, Netley, Southampton, Most of the Old Pictures were Inherited from her Father, the Late Sir Anthony Rothschild, Bt.; Also Choice Pictures of the French School, the Property of the Rt. Hon. Viscountess Harcourt and Old Pictures and Drawings From Other Sources (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, May 6, 1927), 7, as Les Sevreuses.

“The Sale Room: Old French Pictures,” Times (London), no. 44,575 (May 7, 1927): 9, as Les Sevreuses.

“L’Art et la Curiosité: Les grandes ventes à Londres,” Le Figaro (May 16, 1927): 8, as Les Sevreuses.

“À l’Étranger Grande-Bretagne,” La Renaissance de l’Art Français et des Industries de Luxe (June 1927): 303, as Les Sevreuses.

Art Prices Current: A Record of Sale Prices at the Principal London Auction Rooms from October 1926 to July 1927 (London: Art Trade Press Ltd., 1927), 6:273, as Les Sevreuses.

Possibly M[inna] K. P[owell], “Art: Large Crowd at Art Institute Sees Seven Canvases Under Consideration for the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and H. A. Botkin’s Ultra-Modern Water Colors,” Kansas City Times 94, no. 10 (January 12, 1931): 6.

“A Big Gallery Addition: Rembrandt and Hals Paintings to Nelson Group,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 148 (February 12, 1931): 3.

Probably “Half-Million for Art: A Rembrandt in New Purchases for Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 156 (February 20, 1931): 3.

“Kansas City Gets $1,000,000 Art Here: William Rockhill Nelson Trust Buys Paintings by Rubens, Rembrandt and Others. Guelph Objects Included Treasures to Be Placed in New Structure Being Built by Publisher’s Endowment,” New York Times 80, no. 26,690 (February 20, 1931): 16.

“Add Seven Art Works: Group for Nelson Gallery on View at Institute,” Kansas City Star 51, no. 182 (March 18, 1931): 15, as Les Sevreuses or The Weaning.

“Camera Records News Events Here and in Other Parts of the World,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 284 (March 18, 1931): 26, (repro.), as Les Sevreuses.

“Art,” Kansas City Times 94, no. 67 (March 19, 1931): 7, as Weaning.

Kansas City Star 51, no. 193 (March 29, 1931), 6(D), (repro.), as Les Sevreuses, or The Weaning.

“What to See In Kansas City: A guide to principal Points of Interest Presented in the Style of A Baedeker,” Kansas City Star 52, no. 101 (December 27, 1931): 3C, as Les Sevreuses.

“Treasure in Lore of Art: ‘Read,’ says Parsons to Those Who Would Appreciate Works,” Kansas City Times 95, no. 10 (January 12, 1932): 2.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 13, 21, as The Nurses.

“The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, 30, as The Nurses.

Minna K. Powell, “The First Exhibition of the Great Art Treasures: Paintings and Sculpture, Tapestries and Panels, Period Rooms and Beautiful Galleries Are Revealed in the Collections Now Housed in the Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Kansas City Star 54, no. 84 (December 10, 1933): 4C, as The Nurses.

Luigi Vaiani, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand: Critic Views Wide Collection of Beauty as Public Prepares to Pay its First Visit to Museum,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 187 (December 11, 1933): 7.

Paul V. Beckley, “Art News,” Kansas City Journal-Post, no. 193 (December 17, 1933): 2C.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 41, 137, as The Nurses.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 40–41, 46, 168, (repro.), as The Nursemaids.

“French Art is Topic: Sixth in Gallery Lecture Series to be Given Tomorrow; Rare Brocades and Silks Will Be Discussed by Paul Gardner in Session on Wednesday,” Kansas City Star 68, no. 61 (November 17, 1947): 16.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 3rd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1949), 55.

“The Century of Mozart, January 15 through March 4, 1956,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 1, no. 1 (January 1956): 28, as The Nursemaids.

Isabel Stevenson Monro and Kate M. Monro, Index to Reproductions of European Paintings: A guide to pictures in more than three hundred books (New York: H. W. Wilson Company, 1956), 263, as The nursemaids.

Denis Diderot, Salons, ed. Jean Seznec and Jean Adhémar (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960), 2:7, 37, 160, as Les Sevreuses.