Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Joseph Baillio, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.5407.

MLA:

Baillio, Joseph. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.5407.

Born at Carpentras, a town in the old French province of the Comtat Venaissin, Joseph Siffred Duplessis was the son of Joseph Guillaume Duplessis and his wife, Spirite Raynard.1The artist’s distinctive middle name, Siffred (or Siffrein), was the name of a late sixth- and early seventh-century bishop of Carpentras, Siffredus, a former monk in the abbey of Lérins who was venerated as a saint and has a cathedral dedicated to him. He was venerated throughout the region of the Vaucluse, where he performed many good works. Jules Belleudy, J.-S. Duplessis, peintre du roi, 1725–1802 (Chartres: Imprimerie Durand, 1913), 3n1. After his father, a surgeon and amateur artist, had taught him the basic precepts of painting, he began an apprenticeship in nearby Villeneuve-lès-Avignon under the tutelage of Joseph Gabriel Imbert (1654–1740), a Carthusian lay friar and painter of religious compositions. In 1744, Duplessis departed for Rome, where he entered the studio of a considerably more prominent painter from the south of France, Pierre Subleyras (1699–1749). Subleyras allowed Duplessis to copy some compositions with religious themes, but these were at best clumsy exercises. Subleyras was also a portraitist of considerable accomplishment, and it was in that often well-remunerated specialty that Duplessis found his calling. He spent some time in Lyon before venturing forth to Paris, where he settled permanently in 1752.

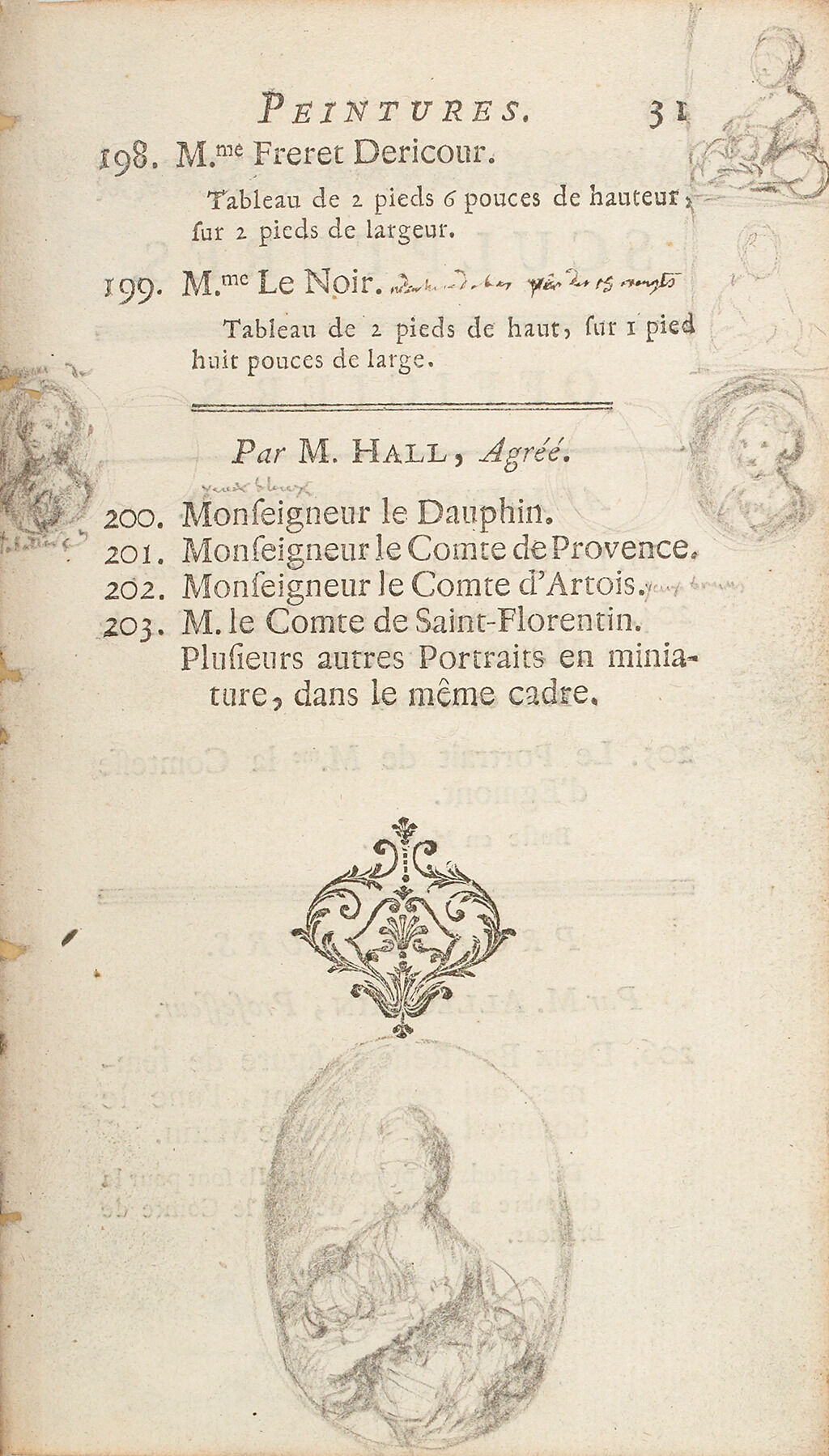

Duplessis registered in the Académie de Saint-Luc, and in 1764 he demonstrated his skills by exhibiting a number of portraits he had recently completed at that guild’s salon in the Hôtel d’Aligre.2At the salon of that institution, the newly matriculated Duplessis exhibited portraits of Joseph Dominique de Cheylus, Bishop of Tréguier; Pierre Jean-Baptiste Gerbier; Dr. Majault; an unnamed prosecutor in the law courts of the Châtelet and official of the Académie de Saint-Luc; and Madame Le Noir. Belleudy, J.-S. Duplessis, peintre du roi, 1725–1802, 319, 323, 326, 329, 338. Slowly, the notoriety he received attracted a well-paying clientele from the upper echelons of the middle class, the landed nobility, and even France’s ruling family. On July 29, 1769, he was elected as an associate (membre agréé) of the prestigious Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture, and this gave him access to the official exhibitionsSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. held biennially in the Salon Carré of the Louvre. That August, he took advantage of the privileges afforded him by this distinction to send to the Salon a total of ten bust- or half-length portraits, including the Nelson-Atkins painting, some of which he had already exhibited at the Académie de Saint-Luc.3According to the exhibition handbook, or livret, the Nelson-Atkins painting was no. 198, M.me Freret Dericourt. The nine other portraits sent by Duplessis to the Salon of 1769, three of which had already been featured in the 1764 exhibition of the Académie de Saint-Luc (see n. 2), depicted the following individuals (their biographies are compiled from Belleudy, J.-S. Duplessis, peintre du roi, 1725–1802): * 190. Louis François, Marquis de Rasilly (1718–1804), a military officer in the Gardes Françaises and a knight in the military order of Saint-Louis (present whereabouts unknown). * 191. François Arnauld, Abbé de Grandchamp (1721–84), a man of the cloth who at various times served as a journalist, linguist, librarian, historian of the Ordre militarie et hospitalier de Saint-Lazare de Jérusalem, and member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (later elected to the Académie Française), who, like Joseph Siffred Duplessis, was a native of Carpentras (Musée Comtadin-Duplessis, Carpentras). * 192. François Joseph Majault, a surgeon in the French army (location unknown). * 193. Pierre Jean-Baptiste Gerbier (1725–88), a famous lawyer known for the eloquence of his oratory and a journalist (with the aforementioned Abbé Arnauld and the writer Jean-Baptiste Antoine Suard, he founded the Journal étranger). According to Belleudy (p. 323), the portrait showed the bewigged Gerbier wearing spectacles. * 194. Monsieur Le-Ras-de-Michel, a hundred-year-old man wearing a dressing gown (location unknown). * 195–196. Monsieur Couturier, a former notary, and his wife (locations unknown). * 197. The Abbé Esprit Jean Fiacre Jourdan, a clergyman from a village north of Carpentras who was attached to the church of Saint-Louis du Louvre and was said to have been a confessor to Marie Antoinette. This may well be the painting sold as lot 2 at Bonham’s in London on July 9, 2008, where it was acquired by a private French collector. But there also exists a larger pastel version of the portrait, oval in shape (Belleudy no. 66; see Jean-Paul Chabaud, Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, 1725–1802: biographie [Mazan: Etudes Comtadines, 2003], 138; and Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800 [(Norwich: Unicorn Press, 2006)], 175). * 198. NAMA portrait. * 199. Madame Le Noir (Fig. 1), whom Gabriel de Saint-Aubin described in an annotation of his copy of the Salon livret as a purveyor of stockings near the Quinze-Vingts, the hospice for the blind (Musée du Louvre, Paris). She has been identified as Madame Alexandre Le Noir, née Louise Catherine Adam, the wife of a hatmaker and the mother of Alexandre Marin Le Noir, founder, during the French Revolution, of the Musée des Monuments Français. A number of critics were struck by the veracity of his portraits, notably the writer who penned a review of the exhibition in Élie Fréron’s periodical, L’Année littéraire:

A portrait painter, recently admitted to the Academy, M. Duplessis excels at capturing likenesses; & we think that we are able to say without offending anyone that there are very few painters in this genre who paint heads with such a variety of color, precise detail, well-modeled & salient effects. His brushstroke is broad, controlled, & uncomplicated. . . . All his portraits are, in general, of an interesting truth.4“Un Peintre de Portrait, nouvellement admis à l’Académie, M. Duplessis, saisit supérieurement la ressemblance; & l’on croit pouvoir dire, sans blesser personne, qu’il est très-peu de Peintres de ce genre qui peignent une tête avec autant de variétés de tons, de détails exacts, de rondeur & d’effets saillans [sic]. Son pinceau est large, moëlleux [sic] & facile. . . . Tous ses portraits sont, en général, d’une vérité intéressante.” Élie-Catherine Fréron, “Lettre XIII. Exposition des Peintures, Sculptures, et Gravûres [sic] de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale,” L’Année Littéraire 5 (1769): 313. All translations by the author unless otherwise indicated.

Although he deplored the growing number of portraits of relatively unknown people that greeted visitors to the Salon, the art critic of the Mémoires secrets commented that “M. Duplessis gives a lot of warmth and expression to his portraits.”5“M. Duplessis donne beaucoup de chaleur & d’expression à ses portraits.” “Lettre II. Sur les Peintures, Sculptures et Gravures de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale, exposée au Sallon du Louvre le 25 Août 1769,” Mémoires secrets pour Servir à l’Histoire de la République des Lettres en France, Depuis MDCCLXII jusqu’à nos jours; ou Journal d’un Observateurs (London: John Adamson, 1780), 13:46. In Denis Diderot’s analysis of the exhibition is an astute observation that set Duplessis apart from the less naturalistic and more flashy portraiture of rivals such as Louis Michel van Loo (1652–1712), Jean Valade (1710–87), and the Swedish-born Alexandre Roslin (1718–93): “Here is an artist named Du Plessis, who has been hiding for ten years and suddenly shows up with three or four really beautiful portraits.”6“Voici un artiste appelé Du Plessis, qui s’est tenu caché pendant une dizaine d’années et qui se montre tout à coup avec trois ou quatre portraits vraiment beaux.” See Jean Seznec, ed., Diderot Salons (Oxford: Clarendon, 1967), 4:49. Diderot saw that Duplessis’s work had much more in common with the portraiture of such artists as a fellow agréé Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805), who showed several works at the 1769 Salon, among them his powerful portrait of the painter Étienne Jeaurat (Musée du Louvre).7Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. 5033.

Duplessis became one of the most accomplished French society and court portraitists at the very end of the Ancien Régimeancien régime: The period in French history from about 1650 to 1789 (before the French Revolution). It was characterized by a divine-right absolute monarchy, a society based upon privileges for the rich and well-connected, and the Catholic Church as the religious establishment. The monarchy fell on August 10, 1792, after months of royal intransigence, and the Revolution entered a new more radical phase. King Louis XVI was executed in January 1793.. Unlike many of his colleagues, he did not generally flatter the faces he scrutinized, revealing such physical imperfections as flaccid skin, pockmarks, florid complexions, and obesity. None of these qualities, however, describe the pleasant face and features Duplessis ascribed to Mme Fréret d’Héricourt. Working slowly, demanding numerous and sometimes tedious sittings from his clients,8In a passage from a page in a bound volume of the manuscripts of Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)’s Souvenirs (Rush Rhees Library, University of Rochester, acc. no. CX103), a text that was not included in the first volume of the autobiography published in Paris in 1835, the artist recalled that in her youth she saw Duplessis in her mother’s apartment. Although she admired his talent, she described him as “tout ennuÿeux” (utterly boring) and claimed, surely not without exaggeration, that few people wanted to have their portraits painted by him because he demanded thirty or forty posing sessions. Duplessis excelled at capturing perfect, characterful, and unidealized likenesses in a technique distinguished by a controlled modeling of flesh, hair, fabrics, furniture, and other accessories; a precise and sensitive attention to realistic detail; a taste for elegant color combinations; and a preference for neutral backgrounds. These were hallmarks of his inimitable and highly recognizable painting style. According to eighteenth-century specialist Thierry Bajou, Duplessis’s honest and sober approach to his art “was to have a great influence on the portraits of Jacques-Louis David [1748–1825].”9Jane Turner, ed., The Dictionary of Art (New York: Grove’s Dictionaries, 1998), 9:399. There is considerable truth to that remark when one recalls a number of David’s equally forthright, middle-class portraits dating from the 1780s.10One thinks in particular of David’s portraits of his uncle, the architect Jacques François Desmaisons (1782; Buffalo AKG Art Museum), of the obstetrician Alphonse Leroy (1783; Musée Fabre, Montpellier), and especially of his father- and mother-in-law, Charles Pierre Pécoul and Madame Pécoul, née Geneviève Jacqueline Potain (1784; Musée du Louvre, inv. nos. 3706 and 3707).

It is not possible to state unequivocally who the “Freret Dericour” lady was, but odds are that she was related by blood or marriage to Nicolas Louis Fréret d’Héricourt, a secretary in the royal Chancery who represented the interests of the French monarchy in the Parliament of Provence.16Fréret d’Héricourt was not the only official attached to the Parliament of Provence who was painted by Duplessis. The artist painted a powerful portrait of Jean François André Le Blanc de Castillon (1719–90), the General Prosecutor (Procureur général) of the Parliament of Provence, shown wearing his official robes. That lost work was engraved the year of the subject’s death by Étienne Beisson. (A copy of the print is in the Fonds de portrait gravés of King Louis-Philippe, now in the Musée national des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, inv. no. GRAV.LP 83.63.1.) In 1778, the bourgeois Fréret purchased from the Crown a lifetime lease of the Commanderie magistrale of Boigny,17For details of his life, see citation in n. 18. The Medieval estate of Boigny was the site of a magisterial commandery of the Military and Hospitaller Order of Saint-Lazarus of Jerusalem. (The head of the order during the reign of Louis XVI was the latter’s brother, the Comte de Provence, who patronized Duplessis and around 1778 and commissioned a bust-length portrait of himself, a work now in the Musée Condé, Chantilly, inv. no. PE 387.) The property leased to Fréret d’Héricourt was located outside of the village of Boigny-sur-Bionne, between the royal forest of Orléans and the Loire river. It retained its status as Crown property until feudal privileges were abolished by the Assemblée Nationale in August of 1789. near Orléans, which presumably carried with it a title and a number of nobiliary prerogatives. In 1785, his social climbing proved costly when the Council of State sitting at Versailles ordered him to pay a tax known as the franc-fief.18The ten-page official decree, dated June 7, 1785, ordering that the tax be paid by Fréret d’Héricourt, was published in pamphlet form on the presses of Jacques Gabriel Clousier in Paris: Arrêt du Conseil d’État du Roi, qui reçois FRANÇOIS MELLIN opposant à celui du 17 Juillet 1731, en conséquence, condamne le Sieur FRÉRET D’HÉRICOURT, Secrétaire du Roi en la Chancellerie, près le Parlement de Provence, au payement de la totalité du Droit de Franc-Fief des Biens Nobles qu’il possède, conformément à la demande qui en avait été formée avant sa récetion audit Office. Du 7 Juin 1785. In 1794, at the age of sixty-two, he was arrested at his house on the rue du Faubourg du Temple.19The Fréret d’Héricourt family seems to have originated in Aix-en-Provence. Archival records relating to the family are preserved in the Bibliothèque Arbaud in that city under “F Freret 268,” and others are in the Musée Paul Arbaud (dossier 1688-A-1). However, when Fréret entered the prison where he was incarcerated, he claimed that he had been born at Herbies, in the Swiss canton of Fribourg, and not in Aix-en-Provence. His somewhat older wife, née Élisabeth Gonnet (or Gounet), who had been born in Lyon around 1730, was apprehended with him. The couple and a number of their servants were brought to trial before the revolutionary tribunal under the so-called “Law of Suspects.” Charged with burying copperware and other metallic objects near a farm owned by the Frérets near Beauvais, all were acquitted.20See “Convention nationale: Tribunal Criminel Révolutionnaire,” Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel 6, no. 177 (March 17, 1794): 716 [repr. in Réimpression de l’Ancien Moniteur, seule histoire authentique et inaltérée de la Révolution française depuis la réunion des États-Généraux jusqu’au Consulat (mai 1789–novembre 1799), vol. 19, Convention Nationale (Paris: Henri Plon, 1861), 716. The official documents concerning the prosecution of the Fréret d’Héricourt couple and their servants are in the Archives nationales de France under the no. W338, dossier 602. It is tempting to speculate that, long before any of this happened, Élisabeth Fréret d’Héricourt was the woman whose portrait was sent by Duplessis to the Salon of 1769. She would have been almost forty years of age at the time.

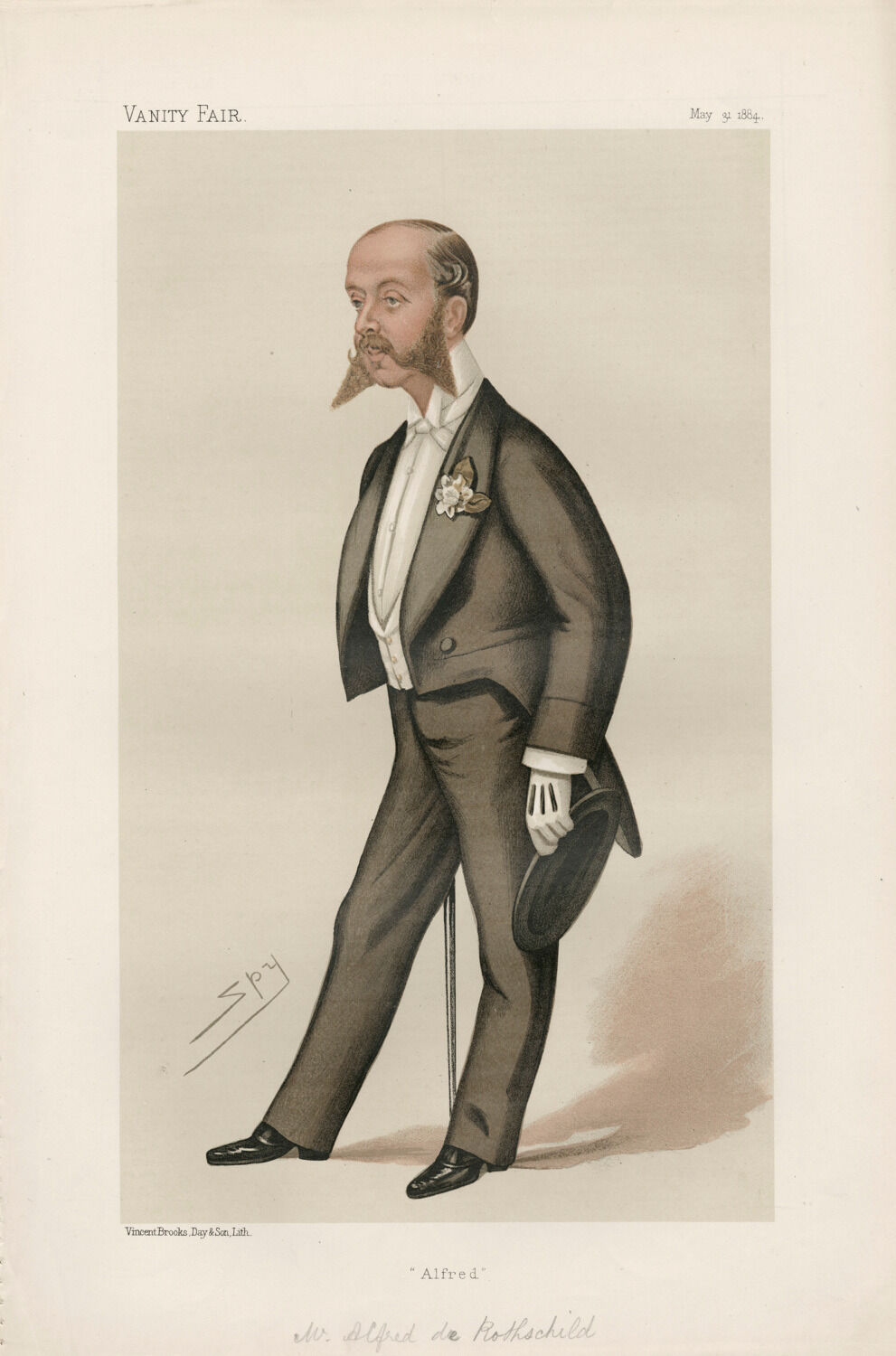

Born in Frankfurt-am-Main on October 9, 1839, Pavel Pavlovich was the first of the two sons of Pavel Nikolaievich Demidov (1798–1840) and his Finnish spouse, Baroness Eva Aurora Charlotta Stjernvall (1808–1902). They derived their enormous fortune from mines in the Ural region and in Siberia, iron foundries, an arms manufactory that supplied weaponry to the Russian imperial armies, and from large deposits of malachite on their lands. Pavel Pavlovich’s first wife, Princess Maria Elimovna Meshcherskaya, died in 1868 soon after she gave birth to a son, the first of the Prince of San Donato’s four children. His distress was so great that he abandoned the palace his grandfather had built and purchased the remnants of the nearby Villa di Pratolino, which after many expansions and improvements came to be known as the Palazzo Demidov or, alternatively, the Villa Demidov. He resided there with his second wife, Princess Elena Petrovna Trubetskaya, and their children, until 1880, when he sold the property to a French business tycoon, Gaston Mestayer. It was then that much of the fabled Demidov art collection was dispersed in a sale organized in large part by the French auctioneer Charles Pillet. The Duplessis painting was included as no. 1439, with an attribution to Drouais, and was reproduced with an engraving of the painting made by the Belgian-born engraver Léopold Flameng (1831–1911).

“A Portrait by Drouais (Picture in the Blue Drawing-room at Aston Clinton)”

Whence come you? Oh my lady fair!

With haunting, wistful smile,

With countenance bereft of guile,

With softly powder’d hair,

With searching eyes that gaze, not stare,

With beauteous garb—not vulgar style.

I love to sit and gaze awhile

Upon your garments rich and rare.

I would that little dog I were

So closely held within your arm,

So warmly shielded from alarm,

So happy in your loving care!

Oh, fair unknown! But known to me—

A friend I on the canvas see.23Constance Flower Battersea, Thoughts in Verse (Norwich: Goose and Son, 1920), 8.

At some point, this inspirational painting returned to Lionel Nathan’s son, Major Edmund de Rothschild. Finding himself in financial straits due to inheritance taxes beginning around 1942, Edmund was forced to sell many of the treasures from the collection of his great-uncle Alfred,24See Edmund de Rothschild, A Gilt-Edged Life: Memoir (London: John Murray, 1998), 166. among them the Duplessis, which by 1950 was the joint property of the Kleinberger Galleries in New York and Edward Speelman, Ltd., in London. Although the identity of the artist and sitter were unknown for decades—even after its acquisition from Kleinberger and Speelman by the Nelson-Atkins Museum in 1953—the artist’s skillful treatment of the luxurious fabrics, plump skin, and attentive pet captivated the museum’s trustees and visitors. Today, with the painting returned to the oeuvre of Joseph Siffred Duplessis, viewers have reason to acquaint themselves with his career and technique, and now they have a glimpse into the possible life of Mme Fréret d’Héricourt as well.

Notes

-

The artist’s distinctive middle name, Siffred (or Siffrein), was the name of a late sixth- and early seventh-century bishop of Carpentras, Siffredus, a former monk in the abbey of Lérins who was venerated as a saint and has a cathedral dedicated to him. He was venerated throughout the region of the Vaucluse, where he performed many good works. Jules Belleudy, J.-S. Duplessis, peintre du roi, 1725–1802 (Chartres: Imprimerie Durand, 1913), 3n1.

-

At the salon of that institution, the newly matriculated Duplessis exhibited portraits of Joseph Dominique de Cheylus, Bishop of Tréguier; Pierre Jean-Baptiste Gerbier; Dr. Majault; an unnamed prosecutor in the law courts of the Châtelet and official of the Académie de Saint-Luc; and Madame Le Noir. Belleudy, J.-S. Duplessis, peintre du roi, 1725–1802, 319, 323, 326, 329, 338.

-

According to the exhibition handbook, or livret, the Nelson-Atkins painting was no. 198, M.me Freret Dericourt. The nine other portraits sent by Duplessis to the Salon of 1769, three of which had already been featured in the 1764 exhibition of the Académie de Saint-Luc (see n. 2), depicted the following individuals (their biographies are compiled from Belleudy, J.-S. Duplessis, peintre du roi, 1725–1802):

- 190. Louis François, Marquis de Rasilly (1718–1804), a military officer in the Gardes Françaises and a knight in the military order of Saint-Louis (present whereabouts unknown).

- 191. François Arnauld, Abbé de Grandchamp (1721–84), a man of the cloth who at various times served as a journalist, linguist, librarian, historian of the Ordre militarie et hospitalier de Saint-Lazare de Jérusalem, and member of the Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (later elected to the Académie Française), who, like Joseph Siffred Duplessis, was a native of Carpentras (Musée Comtadin-Duplessis, Carpentras).

- 192. François Joseph Majault, a surgeon in the French army (location unknown).

- 193. Pierre Jean-Baptiste Gerbier (1725–88), a famous lawyer known for the eloquence of his oratory and a journalist (with the aforementioned Abbé Arnauld and the writer Jean-Baptiste Antoine Suard, he founded the Journal étranger). According to Belleudy (p. 323), the portrait showed the bewigged Gerbier wearing spectacles.

- 194. Monsieur Le-Ras-de-Michel, a hundred-year-old man wearing a dressing gown (location unknown).

- 195–196. Monsieur Couturier, a former notary, and his wife (locations unknown).

- 197. The Abbé Esprit Jean Fiacre Jourdan, a clergyman from a village north of Carpentras who was attached to the church of Saint-Louis du Louvre and was said to have been a confessor to Marie Antoinette. This may well be the painting sold as lot 2 at Bonham’s in London on July 9, 2008, where it was acquired by a private French collector. But there also exists a larger pastel version of the portrait, oval in shape (Belleudy no. 66; see Jean-Paul Chabaud, Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, 1725–1802: biographie [Mazan: Etudes Comtadines, 2003], 138; and Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800 [(Norwich: Unicorn Press, 2006)], 175).

- 198. NAMA portrait.

- 199. Madame Le Noir (Fig. 1), whom Gabriel de Saint-Aubin described in an annotation of his copy of the Salon livret as a purveyor of stockings near the Quinze-Vingts, the hospice for the blind (Musée du Louvre, Paris). She has been identified as Madame Alexandre Le Noir, née Louise Catherine Adam, the wife of a hatmaker and the mother of Alexandre Marin Le Noir, founder, during the French Revolution, of the Musée des Monuments Français.

-

“Un Peintre de Portrait, nouvellement admis à l’Académie, M. Duplessis, saisit supérieurement la ressemblance; & l’on croit pouvoir dire, sans blesser personne, qu’il est très-peu de Peintres de ce genre qui peignent une tête avec autant de variétés de tons, de détails exacts, de rondeur & d’effets saillans [sic]. Son pinceau est large, moëlleux [sic] & facile. . . . Tous ses portraits sont, en général, d’une vérité intéressante.” Élie-Catherine Fréron, “Lettre XIII. Exposition des Peintures, Sculptures, et Gravûres [sic] de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale,” L’Année Littéraire 5 (1769): 313. All translations by the author unless otherwise indicated.

-

“M. Duplessis donne beaucoup de chaleur & d’expression à ses portraits.” “Lettre II. Sur les Peintures, Sculptures et Gravures de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale, exposée au Sallon du Louvre le 25 Août 1769,” Mémoires secrets pour Servir à l’Histoire de la République des Lettres en France, Depuis MDCCLXII jusqu’à nos jours; ou Journal d’un Observateurs (London: John Adamson, 1780), 13:46.

-

“Voici un artiste appelé Du Plessis, qui s’est tenu caché pendant une dizaine d’années et qui se montre tout à coup avec trois ou quatre portraits vraiment beaux.” See Jean Seznec, ed., Diderot Salons (Oxford: Clarendon, 1967), 4:49.

-

Musée du Louvre, Paris, inv. no. 5033.

-

In a passage from a page in a bound volume of the manuscripts of Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)’s Souvenirs (Rush Rhees Library, University of Rochester, acc. no. CX103), a text that was not included in the first volume of the autobiography published in Paris in 1835, the artist recalled that in her youth she saw Duplessis in her mother’s apartment. Although she admired his talent, she described him as “tout ennuÿeux” (utterly boring) and claimed, surely not without exaggeration, that few people wanted to have their portraits painted by him because he demanded thirty or forty posing sessions.

-

Jane Turner, ed., The Dictionary of Art (New York: Grove’s Dictionaries, 1998), 9:399.

-

One thinks in particular of David’s portraits of his uncle, the architect Jacques François Desmaisons (1782; Buffalo AKG Art Museum), of the obstetrician Alphonse Leroy (1783; Musée Fabre, Montpellier), and especially of his father- and mother-in-law, Charles Pierre Pécoul and Madame Pécoul, née Geneviève Jacqueline Potain (1784; Musée du Louvre, inv. nos. 3706 and 3707).

-

Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton describes the spaniel breed like this: “L’épagneul de la petite espèce a le nez plus court que le grand à proportion de la grosseur du corps: les yeux sont gros et à fleur de tête, et la cravate est garnie de soie blanche. C’est de tous les chiens celui qui a la plus belle tête: plus il a les soies des oreilles et de la queue longues & douces, plus il est estimé: il est fidèle et caressant” (The small species of spaniel has a shorter nose than the large one in proportion to the thickness of the body; the eyes are large and protruding from the head, and around the neck is a white, silky tie. Of all dogs, it is the one that has the most beautiful head; the longer and softer the bristles of its ears and tail, the more it is esteemed; it is faithful and caressing). Louis-Jean-Marie Daubenton, “Chien, canis,” Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, par une Société de Gens de lettres, ed. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert (Paris: Briasson et al., 1753), 3:329.

-

Sometimes the family name of Count Pavel Pavlovich is spelled Demidoff, but this was not in regular use until after February Revolution of 1917 when the family lost its fortune. “Demidov Family,” Encyclopedia Britannica, May 30, 2013, https://www.britannica.com

/topic ./Demidov-family -

Explication des Peintures, Sculptures et Gravures, de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale, Dont l’exposition a été ordonnée, suivant l’intention de Sa Majeste [sic], par M. le Marquis de Marigny, Conseiller du Roi en ses Conseils, Commandeur de ses Ordres, Lieutenant Général des Provinces de Beauce et Orléanois, Directeur et Ordonnateur général des Bâtimens [sic] Du Roi, Jardins, Arts, Académies et Manufactures Royales; Gouverneur des villes de Blois, Suevres [sic] et Menars, et Capitaine Gouverneur du Château de Blois, exh. cat. (Paris: Herissant Pere, 1769), nos. 50–61.

-

Pierre Rosenberg, The Age of Louis XV: French Painting, 1710–1774, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1975), 38.

-

Explication des peintures, p. 31, no. 198 (“Mme. Freret Dericour. Tableau de 2 pieds 6 pouces de hauteur, sur 2 pieds de largeur”). Saint-Aubin’s illustrated copy is at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Estampes et photographie, RESERVE 8-YD2-1133.

-

Fréret d’Héricourt was not the only official attached to the Parliament of Provence who was painted by Duplessis. The artist painted a powerful portrait of Jean François André Le Blanc de Castillon (1719–90), the General Prosecutor (Procureur général) of the Parliament of Provence, shown wearing his official robes. That lost work was engraved the year of the subject’s death by Étienne Beisson. (A copy of the print is in the Fonds de portrait gravés of King Louis-Philippe, now in the Musée national des Châteaux de Versailles et de Trianon, inv. no. GRAV.LP 83.63.1.)

-

For details of his life, see citation in n. 18. The Medieval estate of Boigny was the site of a magisterial commandery of the Military and Hospitaller Order of Saint-Lazarus of Jerusalem. (The head of the order during the reign of Louis XVI was the latter’s brother, the Comte de Provence, who patronized Duplessis and around 1778 and commissioned a bust-length portrait of himself, a work now in the Musée Condé, Chantilly, inv. no. PE 387.) The property leased to Fréret d’Héricourt was located outside of the village of Boigny-sur-Bionne, between the royal forest of Orléans and the Loire river. It retained its status as Crown property until feudal privileges were abolished by the Assemblée Nationale in August of 1789.

-

The ten-page official decree, dated June 7, 1785, ordering that the tax be paid by Fréret d’Héricourt, was published in pamphlet form on the presses of Jacques Gabriel Clousier in Paris: Arrêt du Conseil d’État du Roi, qui reçois FRANÇOIS MELLIN opposant à celui du 17 Juillet 1731, en conséquence, condamne le Sieur FRÉRET D’HÉRICOURT, Secrétaire du Roi en la Chancellerie, près le Parlement de Provence, au payement de la totalité du Droit de Franc-Fief des Biens Nobles qu’il possède, conformément à la demande qui en avait été formée avant sa récetion audit Office. Du 7 Juin 1785.

-

The Fréret d’Héricourt family seems to have originated in Aix-en-Provence. Archival records relating to the family are preserved in the Bibliothèque Arbaud in that city under “F Freret 268,” and others are in the Musée Paul Arbaud (dossier 1688-A-1). However, when Fréret entered the prison where he was incarcerated, he claimed that he had been born at Herbies, in the Swiss canton of Fribourg, and not in Aix-en-Provence.

-

See “Convention nationale: Tribunal Criminel Révolutionnaire,” Gazette Nationale ou Le Moniteur Universel 6, no. 177 (March 17, 1794): 716 [repr. in Réimpression de l’Ancien Moniteur, seule histoire authentique et inaltérée de la Révolution française depuis la réunion des États-Généraux jusqu’au Consulat (mai 1789–novembre 1799), vol. 19, Convention Nationale (Paris: Henri Plon, 1861), 716. The official documents concerning the prosecution of the Fréret d’Héricourt couple and their servants are in the Archives nationales de France under the no. W338, dossier 602.

-

See paper label with ink script, partially encapsulated, on a stretcher on the reverse of painting: “Purchased for A de Rothschild Esq / by Thos Agnew Sons from the / [S]a[n] Donato Collection March 1880.”

-

Rothschild left his London house to a woman widely believed to be his natural daughter, Almina Wombell, wife of the Earl of Carnarvon, who with her generous dowry funded the archaeological expedition that led to the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt.

-

Constance Flower Battersea, Thoughts in Verse (Norwich: Goose and Son, 1920), 8.

-

See Edmund de Rothschild, A Gilt-Edged Life: Memoir (London: John Murray, 1998), 166.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Sophia Boosalis, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.2088.

MLA:

Boosalis, Sophia. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.2088.

The portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt is among a small minority of female sitters painted by Joesph Siffred Duplessis.1Duplessis is estimated to have painted less than 200 portraits during his career, the majority of which represent male sitters. Katharine Baetjer, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis,” in French Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art from the Early Eighteenth Century through the French Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 194. For information regarding the attribution of the portrait, see the accompanying curatorial essay by Joseph Baillio. The portrait was executed on a coarse, plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas with several weave irregularities. There is limited information about the original canvas, as the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. are no longer present. The painting appears to be close to its original dimensions as cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. is visible along all edges, despite the close cropping of the vase in the upper-left corner. The radiographX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. of the portrait shows dark bands extending perpendicularly from the left and right edges, suggesting a thinner groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. application at the original attachment points.2Digital radiograph, no. 600, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 53-80. The canvas was prepared with a double ground typical of the period: a brownish-red lower layer and a light gray upper layer (Fig. 6).3Elma O’Donoghue, Rafael Romero, and Joris Dik, “French Eighteenth-Century Painting Techniques,” Studies in Conservation 43 (sup1) (1998): 185–89.

No underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. was detected beneath the paint layers using infrared (IR) photographyinfrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700-1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film. or examination with the stereomicroscope.4Although an underdrawing was not detected, Duplessis may have used a non-carbon-based material, such as chalk or crayon, to lay in the initial idea. For eighteenth-century artistic practices, see O’Donoghue, Romero, and Dik, “French Eighteenth-Century Painting Techniques,” 187. Duplessis is known to have made a preparatory study of Benjamin Franklin in pastel before executing his oil portrait due to the sitter’s dislike of posing. However, this was not a common practice for the artist. Katherine Baetjer, Marjorie Shelley, Charlotte Hale, and Cynthia Moyer, “Benjamin Franklin, Ambassador to France: Portraits by Joseph Siffred Duplessis,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 52 (2017): 61. Duplessis initially blocked in major elements of the portrait using various colors to serve as an underpaintingunderpainting: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called ébauche.. On top of the gray background, thin paint layers were blended to create subtle transitions between light and shadow.5The portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, as represented in the etching from the 1880 Demidov-San Donato sale catalogue, is depicted with a dramatic shadow in the background. However, the accuracy of the print remains uncertain, as it omits details in the depiction of the vase. Léopold Flameng (1831–1911), Portrait of a Woman (Madame Fréret d’Héricourt), 1880, etching on paper, 12 1/8 x 9 5/16 in. (30.8 x 23.7 cm), British Museum, London, 1881,0813.87.

Duplessis blocked in the sitter’s face with opaque beige paint before constructing the facial features with thin applications of paint. Dark brown, brownish-red, and bright pink paint were used to render the nose and lips, as well as outline the contours of the sitter’s eyes. Duplessis proceeded to apply dark brown and yellow ochre paint to form the iris, thin black lines to strengthen the contours of the eyelid and the shape of the pupil, and a small dab of white paint to create a highlight in the pupils and along the inner edge of the eyes. A transparent magenta, most likely a red lake, marks the separation of the lips and darkens each nostril. Madame Fréret d’Héricourt’s smooth skin consists of wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. blending of the fluid, opaque layers over the beige underpainting (Fig. 7). This same technique is evident in the sitter’s chest and arms, where there are little to no visible brushstrokes. Duplessis added shades of pink to accentuate the sitter’s rosy complexion, complemented by thin brown and gray paint to strengthen areas of shadow and mid-tones. A few streaky brushstrokes of white paint, applied wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color., highlight the sitter’s cheeks and nose.

Duplessis efficiently constructed the pearl necklace, using the beige paint of the neck as a mid-tone, and simply adding shadows in brown and cool gray. Using a fine-tipped brush, dabs of white paint portray the reflection of light on each individual pearl (Fig. 8). This straightforward painting technique was also applied to the sitter’s lace bonnet, where the gray background remains visible to mimic the transparency of the fabric.

The fabrics in the sitter’s costume were skillfully rendered using distinct tonal underlayers and varied brushwork to convey different textures. In the pink and white dress, Duplessis appears to have created broad passages of color over an opaque, light pink underpainting (Fig. 9). Shades of pink, magenta, light gray, and white were layered to build these passages, with instances of wet-over-wet application. Delicate touches with a fine brush were used to create the embroidered floral design.

Duplessis underpainted the outer gown with opaque yellow and ochre tones, followed by wet-into-wet blending to create seamless transitions. Black, brown, and orangish-brown glazesglaze: A transparent, oil or resin-rich paint application that influences the tonality of the underlying paint. reinforced the shadows and defined the folds. Large dabs of brown and yellow paint were added wet-over-wet to achieve the shimmering appearance of a dot pattern in the silky fabric.

Unlike other parts of the sitter’s costume, Duplessis used drier brushwork over an opaque pale brown paint to capture the soft texture of the dark fur lining. Duplessis also meticulously painted the lace of the false sleeves over an ochre and dark brown underpainting, incorporating cool gray shadows and light beige highlights. The false sleeves appear to have been completed in one session, with wet-into-wet blending in the lower layers, along with finely painted, wet-over-wet crisscrossing brushstrokes to depict the delicate lace (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the lace sleeve in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69)

Fig. 10. Photomicrograph of the lace sleeve in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69)

Fig. 11. Detail of the dog in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69)

Fig. 11. Detail of the dog in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69)

The dog was painted in tandem with the sitter, as the paint of her proper left arm and floral dress subtly extend beneath the animal, while the yellow outer gown slightly covers it. The fur was made up of overlapping brushstrokes of white, light gray, beige, and brown paint, applied wet-over-wet with areas of impastoimpasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. (Fig. 11). Dark glazes were later added to model the shadows and define the dog’s contours after the eyes and snout were executed. As with the sitter, a limited palette of pink, ochre, brownish-red, brown, black, and white was used for the dog’s facial features. Microscopic examination revealed that the sequence of paint application in the dog’s eyes closely mirrors that of the sitter’s eyes (Fig. 12). Parallels in the techniques used to paint the dog and sitter suggest that the artist intended to draw a visual connection and highlight the resemblance between the two, perhaps alluding to eighteenth-century beliefs surrounding the depiction of aristocrats with their companion animals.6See Joanna M. Gohmann, “The Four-Legged Sitter: A Note on the Significance of the Dog in Jean-Marc Nattier’s La Marquise D’Argenson,” Journal of the Walters Art Museum 73 (2018): 96–100.

Fig. 12. Details of sitter’s and dog’s eyes in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69)

Fig. 12. Details of sitter’s and dog’s eyes in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69)

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of the yellow outer gown in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69). White arrows point to turquoise blue paint below the yellow paint layer.

Fig. 13. Photomicrograph of the yellow outer gown in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69). White arrows point to turquoise blue paint below the yellow paint layer.

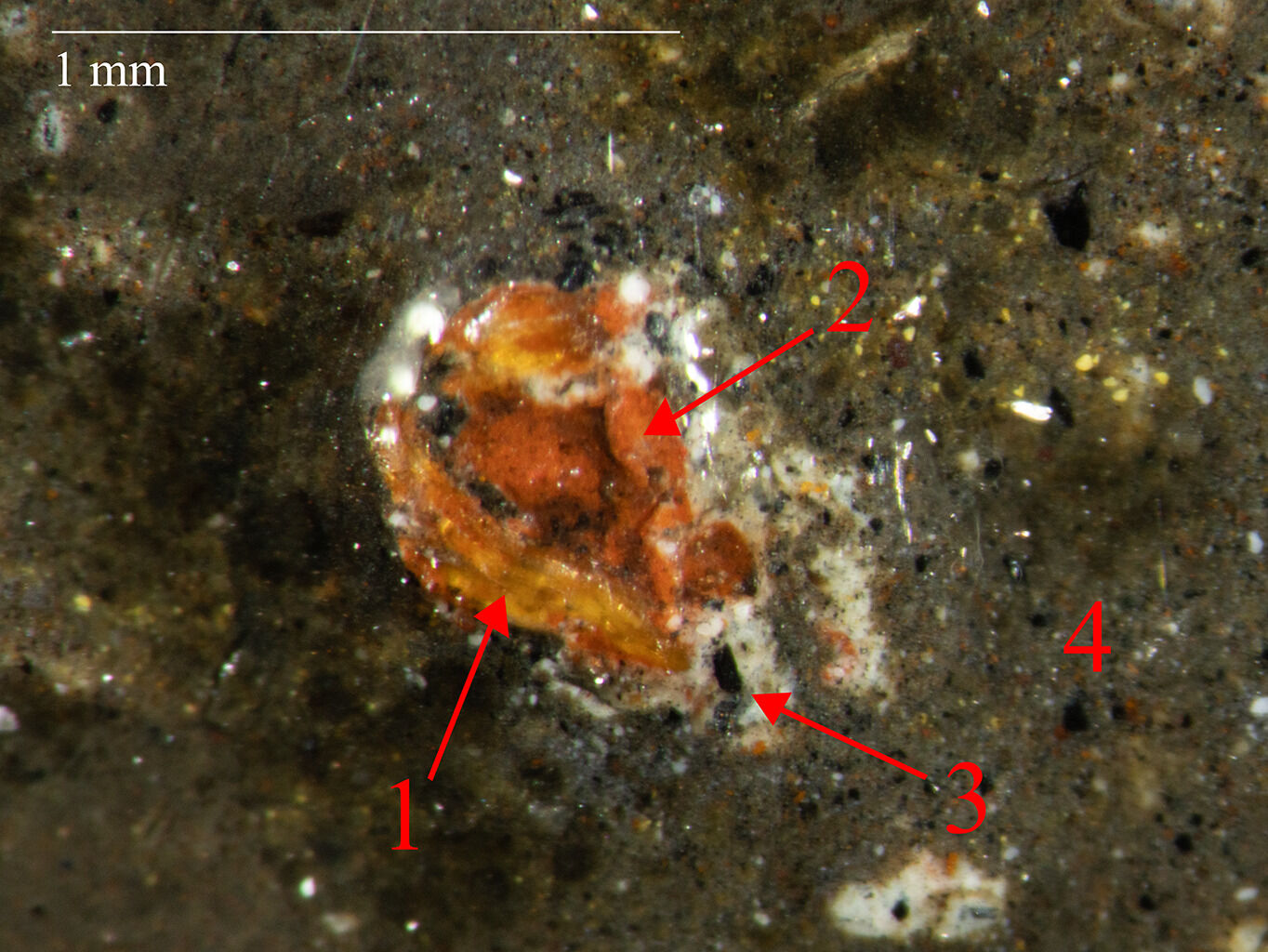

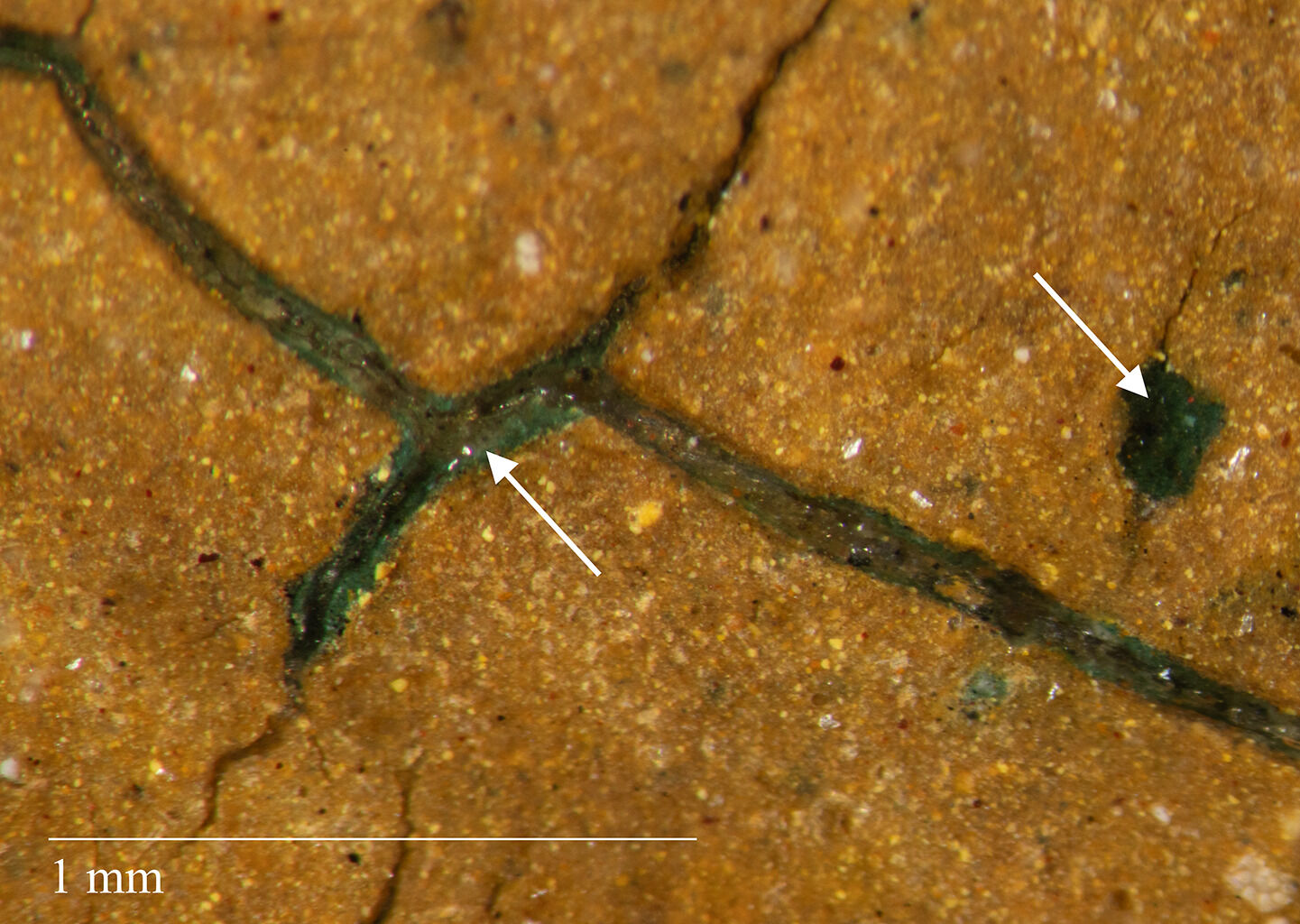

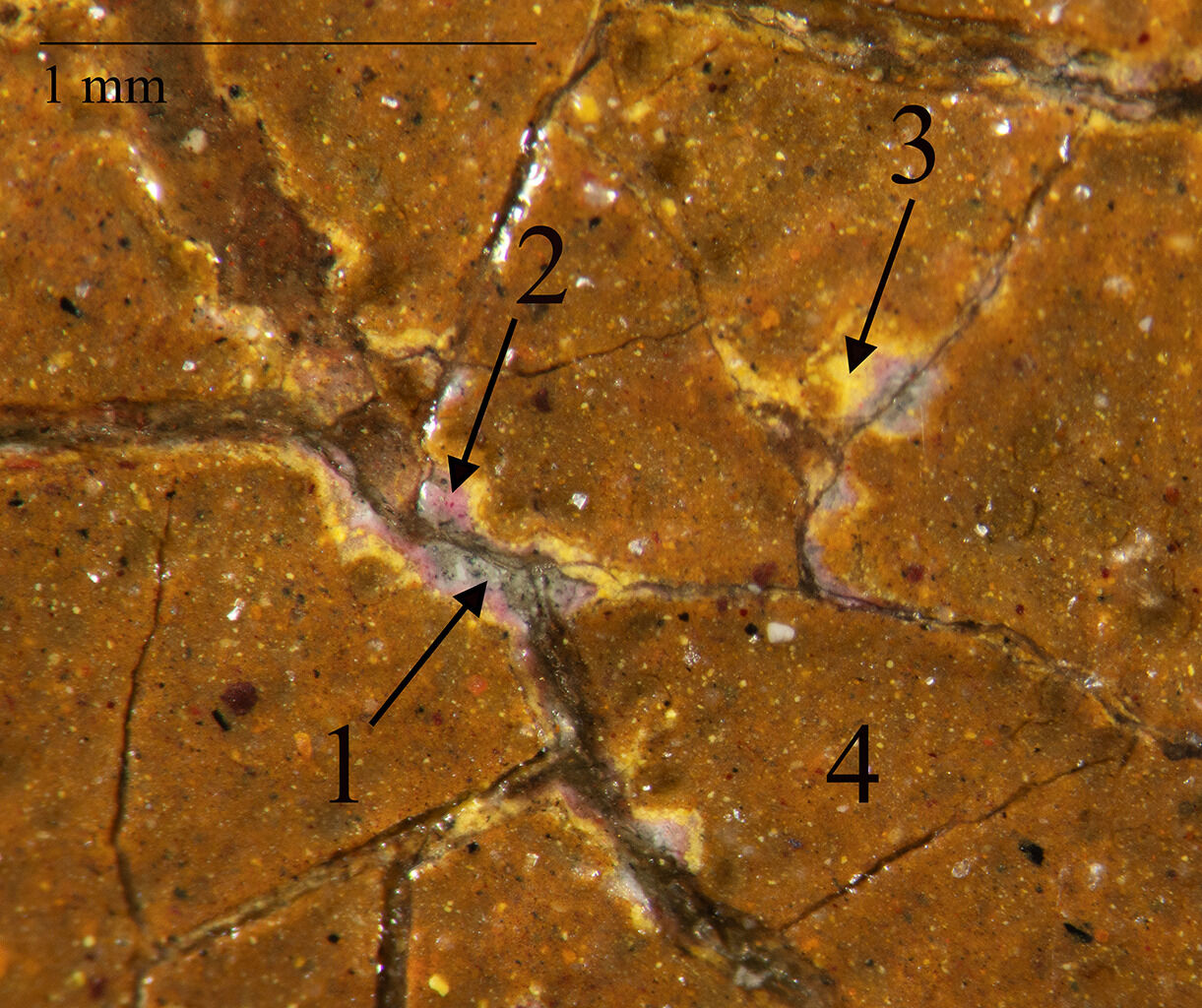

Duplessis appears to have made several adjustments to the sitter’s costume during the painting process. These alterations suggest that the yellow outer gown was a later addition to the portrait. Microscopic examination revealed traces of pink paint, likely associated with the floral dress, visible in the mechanical cracksmechanical cracks: Cracks, either localized or overall, that form in response to movement or stress. of both sleeves in the golden-yellow gown. Duplessis subtly widened the proper left sleeve by adding a fold over the dark chair. As part of this modification, the lower portion of the yellow gown was also extended. A modulating turquoise paint layer is present beneath the outer part of the lace sleeve and the outer gown, although it does not appear to have served as a preparatory layer for the sitter’s attire (Fig. 13). Duplessis further enlarged the outer gown by adding yellow fabric beneath the dog’s paw, a modification made after the dog and pink dress had already been painted. A modulating pink paint layer, likely related to the sitter’s pink dress, is visible beneath the yellow and ochre layers of the outer gown (Fig. 14).

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69), showing the paint structure of the yellow outer gown below the dog’s extended paw, with numbers corresponding to the order of application: light gray ground (1), light pink layer (2), bright yellow layer (3), and ochre paint layer (4)

Fig. 14. Photomicrograph of Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69), showing the paint structure of the yellow outer gown below the dog’s extended paw, with numbers corresponding to the order of application: light gray ground (1), light pink layer (2), bright yellow layer (3), and ochre paint layer (4)

Fig. 15. Details of the the proper right sleeve in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69). The annotated, normal-light image (right) and the digital x-radiograph (left) highlight the alterations: the green line indicates the change to the arm, while the red line shows the modifications to the sleeve.

Fig. 15. Details of the the proper right sleeve in Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt (1768–69). The annotated, normal-light image (right) and the digital x-radiograph (left) highlight the alterations: the green line indicates the change to the arm, while the red line shows the modifications to the sleeve.

The radiograph reveals dense brushstrokes, applied in a sweeping band, below the sleeve of the yellow outer gown and extending into the background, suggesting a change in the position of the lace sleeve (Fig. 15). Microscopic examination revealed pinkish beige paint beneath the upper layers of the dog’s fur, a change made visible due to extensive abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. of the upper paint that occurred during a past solvent cleaning. Duplessis appears to have altered the placement of the sleeve to create the illusion of foreshortening in the arm while adjusting the placement of the sitter’s hand.

The portrait was treated at least once prior to the Nelson-Atkin’s acquisition in 1953. During this treatment, the canvas was glue-linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive., the tacking margins were removed, and the paint surface was cleaned with overly strong solvent.7James Roth, November 18,1953, technical report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 53-80. Extensive loss of thin upper paint layers occurred throughout the composition, and microscopic examination reveals pitting, characterized by numerous small, circular depressions in the paint surface. The interstices of the paint are filled with discolored natural resin varnish which enhances the canvas weave, already made more prominent by the lining process. During a 2009 treatment, efforts were made to visually reintegrate the abraded paint surface,8Mary Schafer, March 4, 2009, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 53-80. and the extent of the retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. campaign is evident under ultraviolet (UV) fluorescenceultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. (Fig. 16).

Notes

-

Duplessis is estimated to have painted less than 200 portraits during his career, the majority of which represent male sitters. Katharine Baetjer, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis,” in French Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art from the Early Eighteenth Century through the French Revolution (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019), 194. For information regarding the attribution of the portrait, see the accompanying curatorial essay by Joseph Baillio.

-

Digital radiograph, no. 600, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 53-80.

-

Elma O’Donoghue, Rafael Romero, and Joris Dik, “French Eighteenth-Century Painting Techniques,” Studies in Conservation 43 (sup1) (1998): 185–89.

-

Although an underdrawing was not detected, Duplessis may have used a non-carbon-based material, such as chalk or crayon, to lay in the initial idea. For eighteenth-century artistic practices, see O’Donoghue, Romero, and Dik, “French Eighteenth-Century Painting Techniques,” 187. Duplessis is known to have made a preparatory study of Benjamin Franklin in pastel before executing his oil portrait due to the sitter’s dislike of posing. However, this was not a common practice for the artist. Katherine Baetjer, Marjorie Shelley, Charlotte Hale, and Cynthia Moyer, “Benjamin Franklin, Ambassador to France: Portraits by Joseph Siffred Duplessis,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 52 (2017): 61.

-

The portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, as represented in the etching from the 1880 Demidov-San Donato sale catalogue, is depicted with a dramatic shadow in the background. However, the accuracy of the print remains uncertain, as it omits details in the depiction of the vase. Léopold Flameng (1831–1911), Portrait of a Woman (Madame Fréret d’Héricourt), 1880, etching on paper, 12 1/8 x 9 5/16 in. (30.8 x 23.7 cm), British Museum, London, 1881,0813.87.

-

See Joanna M. Gohmann, “The Four-Legged Sitter: A Note on the Significance of the Dog in Jean-Marc Nattier’s La Marquise D’Argenson,” Journal of the Walters Art Museum 73 (2018): 96–100.

-

James Roth, November 18,1953, technical report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 53-80.

-

Mary Schafer, March 4, 2009, treatment report, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 53-80.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, with Pegeen Blank, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L., with Pegeen Blank. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, with Pegeen Blank, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L., with Pegeen Blank. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

Possibly to the presumed sitter, Élisabeth Fréret d’Héricourt (née Gonnet, b. ca. 1730, Lyon) or her husband, Nicolas Louis Fréret d’Héricourt (b. ca. 1732, Herbies/Vispens, Fribourg, Switzerland), Paris and Beauséjour, Beauvais, France, 1769 [1];

Count Pavel Pavlovich Demidov, 2nd Prince of San Donato (1839–85), Villa San Donato, Polverosa, Italy, by 1880 [2];

Purchased at his sale, Palais de San Donato: Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement, Tableaux, Villa San Donato, Polverosa, March 15, 1880, lot 1439, as by François-Hubert Drouais, Portrait de Femme, by Thomas Agnew and Sons, London, no. 1402, March 15–April 7, 1880 [3];

Purchased from Agnew by Alfred Charles de Rothschild (1842–1918), London and Halton, Buckinghamshire, England, April 7, 1880–at least 1884 [4];

To his cousin, Constance Flower, Lady Battersea (née de Rothschild, 1843–1931), Aston Clinton, Buckinghamshire, by 1918 [5];

Possibly inherited by her first cousin twice removed, Rosemary de Rothschild (1913–2013), 1931 [6];

To Edmund Leopold de Rothschild (1916–2009), London and Exbury Estate, Hampshire, England, until possibly 1942 [7];

With Edward Speelman Ltd., London, on joint account with F. Kleinberger Galleries, New York, no. 1187, as by Francois-Hubert Drouais, Woman with dog on her Lap, December 1950–December 8, 1953 [8];

Purchased from Speelman and Kleinberger by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1953.

Notes

[1] Madame Fréret d’Héricourt’s maiden name is also variously spelled Gounet or Gonet. For more on the Fréret d’Héricourts, see the curatorial entry by Joseph Baillio, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1769,” in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.5407.

A man named Nicolas Louis Freret, who had been born in Vispens, diocese of Fribourg in Switzerland, became a naturalized French citizen in 1756. See “FRERET (Nicolas Louis),” Archives nationales, Paris, cote P//2595, https://francearchives.gouv.fr/fr/facomponent/366dc84b6227fb573c26baf3cc39ea1561168541 In 1794, the Fréret d’Héricourts were acquitted by the Revolutionary Tribunal for the charge of burying and hiding various valuable metal objects. At the time, the family lived at rue du Faubourg du Temple in Paris and also owned a house in Beauséjour, Beauvais.

[2] This constituent is also sometimes known as Paul Demidoff. His grandfather Nikolai Nikitich Demidov (1773–1828) was an art collector active in Paris, Russia, and Italy. He began building the Villa San Donato in 1827, but he died the following year before it was completed. His first son and Pavel II’s father, Pavel Nikolaievich Demidov (1798–1840), probably inherited Villa San Donato but seems to have not been interested in art due to ill health. Nikolai’s younger son, Count Anatoly Nikolaievich Demidov (1813–70), inherited the Villa San Donato next, and a few months after his brother’s death in 1840, he was named the 1st Prince of San Donato (so that his new wife princess Mathilde-Létizia Bonaparte could retain her title). Anatoly was an active art collector in Paris. When he died without legitimate issue, his nephew Count Pavel Pavlovich Demidov, 2nd Prince of San Donato (1839–85), inherited the Villa San Donato. He may have inherited the painting from any of these relatives. The 2nd Prince spent much of his life between Paris, Vienna, Kiev, and St. Petersburg, and he also collected art. According to Juliette Adam, In Memoriam. Prince Paul Demidoff, Mort le 26 janvier, 1885, trans. H. Guedalla (London, 1885), p. 6, “In 1874, he returned [from Kiev] to Petersburg, then to San Donato, which he continued to enrich with objects of art.” In 1872, he bought a property formerly belonging to the Medici and transformed it into the Villa Pratolino. It seems unlikely that the painting ever hung in one of the buildings on this second property since by 1880 it was hanging in the boudoir of the Villa San Donato.

[3] See National Gallery, London, Thomas Agnew Archive, NGA 27/1/1/6, Picture Stock Book 4, p. 70–71. See also paper label with ink script, partially encapsulated, on stretcher reverse of painting: Purchased for A de Rothschild Esq / by Thos Agnew Sons from the / [S]a[n] Donato Collection March 1880.

[4] The painting may have hung in Halton, Alfred’s mansion in Buckinghamshire, until his death in January 1918. See Rothschild Archive, London, Alfred Charles de Rothschild (1842–1918): will and estate papers, RAL 000/174, Halton, “Schedule of Furniture and General Contents of the Mansion and Outbuildings, Messers. Knight, Frank and Rutley, Auctioneers and Values,” August 1918, p. 127, as Library–Drouais, A three-quarter length portrait of a lady. However, as of 1884, Alfred also owned another Drouais, known then as Portrait of Mademoiselle Duthé (or Dutet); see Charles Davis, A Description of the Works of Art Forming the Collection of Alfred de Rothschild, vol. 1 (London: [Chiswick Press], 1884), nos. 50 and 198. If the Duplessis painting was still in Alfred’s collection at the time of his death, it would have been inherited, along with his estate, by his nephew, Lionel Nathan de Rothschild (1882–1942). Lionel sold the estate to the War Office in May 1918, but retained ownership of the contents of the mansion.

[5] See small paper label on upper left corner of the stretcher reverse, faint graphite, which appears to read: Lord Barters[z?]e. The first and last Lord Battersea (né Cyril Flower, 1843–1907) received his title to Baron on September 5, 1892. In 1877, he married Constance de Rothschild, who was Alfred de Rothschild’s first cousin. By 1918, the painting hung in the “Blue Drawing Room” at Aston Clinton, which was Lady Battersea’s family home. See Constance Flower Battersea, Thoughts in Verse (Norwich: Goose and Son, 1920), 8. After the death of Lady Battersea’s mother, Louisa, in 1910 and Alfred de Rothschild in 1918 (the last of Lionel Nathan de Rothschild’s sons), Aston Clinton and its contents were inherited by Lady Battersea’s first cousin once removed, N. Charles de Rothschild (1877–1923). Throughout this time, Lady Battersea continued to live there. After Charles’ death in 1923, his executors convinced Lady Battersea to sell Aston Clinton and its contents, although the Duplessis painting does not appear in the sales catalogues.

[6] The painting may have gone with Lady Battersea to another one of her houses after 1923. She leased a London mansion at 10, Connaught Place and owned an estate called The Pleasaunce in Overstrand, Norfolk, England. After Lady Battersea’s death in 1931, these houses were inherited by her first cousin twice removed, Rosemary de Rothschild. See Lucy Cohen, Lady de Rothschild and her daughters, 1821–1931 (London: John Murray, 1937), 285. According to Michael Hall, curator of Exbury House, in an email to Meghan Gray, Curatorial Associate, October 22, 2018, NAMA curatorial files, because Rosemary was only 18 at the time, her father, Lionel Nathan de Rothschild (1882–1942), took over Rosemary’s interest in the estates. He sold The Pleasaunce in 1936 and 10, Connaught Place, sometime after 1931, but the painting is not listed in either sales catalogue.

[7] In his memoirs, Edmund de Rothschild, A Gilt-Edged Life: Memoir (London: John Murray, 1998), 7–8, Edmund de Rothschild recounts inheriting his great-uncle’s estate and artwork through his father and Alfred de Rothschild’s nephew, Lionel Nathan de Rothschild (1882–1942), London. It is possible that this painting was among the works he inherited in this manner. Although Edmund inherited his art collection from Lionel, the presence of Lady Battersea and possibly Rosemary de Rothschild in the provenance makes a direct transfer between Lionel and Edmund unlikely. Edmund was forced to sell most of the family’s fine art and furniture in 1942 in order to raise funds for estate duties. Many of the paintings were sold to Thomas Agnew and Sons and to the Finnish dealer Tancred Borenius (1885–1948), who was also a part-time advisor to Sotheby’s. This painting may have been one of them.

A handwritten note in the NAMA curatorial files amends the provenance listed in the accessioning paperwork, crossing out the name Edmund and replacing it with Edouard. Alfred’s second cousin, Edouard Alphonse de Rothschild (1868–1949) was a banker and art collector who lived in Paris. The German National Socialist (Nazi) regime confiscated most of his art collection in late 1941. This version of the provenance, in which Edmund is replaced with Edouard, was published in the 1975 exhibition catalogue titled The Age of Louis XV. French Painting, 1715–1774. It is not clear who made this amendment, and though it appears very likely to have been an error, research is being conducted in the appropriate archives to verify the painting was in Edmund’s possession and that there are no known claims to the painting.

[8] See The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, F. Kleinberger Galleries (New York, N.Y.), Stock cards, 1897–1973, and clipping file.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of M. de Héricourt, 1771, oil on canvas, unknown dimensions, location unknown, cited in Explication des Peintures, Sculptures, et Gravures, de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale [Salon de 1771] (Paris: Herissant Père, 1771), no. 211, p. 37.

Reproductions

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

Leopold Flameng (1831–1911), after Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait de femme tenant un chien sur ses genoux (Portrait of a Woman Holding a Dog on Her Lap), 1880, etching, 12 x 9 7/16 in. (30.5 x 24 cm), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Known Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

Gabriel Jacques de Saint-Aubin (1724–80), after Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Sketch of M.me Freret Dericour, 1769, graphite in margin of Salon Livret, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, département Estampes et photographie, RESERVE 8-YD2-1133, p. 31.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

Salon de 1769, Salon du Louvre, Paris, opened August 25, 1769, no. 198, as M.me Freret Dericourt.

Exhibition of Masterpieces Honoring Hazel Barker King, Retiring Curator of the Allen Memorial Art Museum, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, June 1–15, 1952, no. 2, erroneously as by Francois Hubert Drouais, Portrait of a Lady with a Dog.

French Eighteenth Century Painters: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Education Program of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, Minneapolis Institute of Arts, October 6–November 2, 1954; Wildenstein, New York, November 16–December 11, 1954, no. 7, erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Portrait of a Lady Holding a Dog.

The Century of Mozart, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 15–March 4, 1956, no. 29, erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Lady Holding A Dog.

Age of Elegance: The Rococo and its Effect, Baltimore Museum of Art, April 25–June 14, 1959, no. 9.

school exhibit, Corpus Christi Art Foundation, TX, March 3–29 or March 12–25, 1961, no cat.

The Age of Louis XV: French Painting 1715–1774, Toledo Museum of Art, October 26–December 7, 1975; The Art Institute of Chicago, January 10–February 22, 1976; National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, March 21–May 2, 1976, no. 33, as Portrait de Mme Freret-Déricour.

Those Beguiling Women, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, September 27–October 30, 1983, as Portrait of Mme. Freret-Dericour.

Picturing French Style: Three Hundred Years of Art and Fashion, Mobile Museum of Art, Mobile, AL, September 6, 2002–January 5, 2003; Norton Museum of Art, West Palm Beach, FL, February 4–April 27, 2003, hors cat.

Joseph-Siffred Duplessis (1725–1802): Le Van Dyck de la France, La Bibliothèque-Musée Inguimbertine de Carpentras, France, June 14–September 28, 2025.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Joseph Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, 1768–69,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.314.4033.

Explication des Peintures, Sculptures, et Gravures, de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale, Dont l’exposition a été ordonnée, suivant l’intention de Sa Majesté, par M. le Marquis de Marigny, Conseiller du Roi en ses Conseils, Commandeur de ses Ordres, Lieutenant Général des Provinces de Beauce et Orléanois, Directeur et Ordonnateur général des Bâtimens Du Roi, Jardins, Arts, Académies et Manufactures Royales; Gouverneur des villes de Blois, Suèvres et Menars, et Capitaine Gouverneur du Château de Blois, exh. cat. (Paris: Herissant Pere, 1769), 31, as M.me Freret Dericourt.

Élie-Catherine Fréron, “Lettre XIII. Exposition des Peintures, Sculptures et Gravûres de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale,” L’Année Littéraire 5 (1769): 313, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Collection Deloynes, vol. 9, no. 128, p. 311.

Lettre sur L’Exposition Des Ouvrages De Peinture et de Sculpture au Sallon [sic] du Louvre 1769 (Paris, 1769), Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Collection Deloynes, vol. 49, no. 120, p. 43.

“Lettre II. Sur les Peintures, Sculptures, et Gravures de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale, exposée au Sallon [sic] du Louvre, le 25 Août 1769,” Mémoires Secrets pour Servir à l’Histoire de la République des Lettres en France, Depuis MDCCLXII jusqu’à nos jours; ou Journal d’un Observateur (London: John Adamson, 1780), 13:46.

“Catalogue Général des Ouvrages Exposés au Salon du Louvre, Depous 1699 jusqu’en 1789: Première Partie; Tableaux et Dessins,” Le Cabinet de l’amateur et de l’antiquaire (Paris: Librairie Firmin-Didot frères, fils et cie, 1845), 4:182, as Madame Freret Dericour.

Charles Pillet, Palais de San Donato: Catalogue des Objets d’Art et d’Ameublement Tableaux (Paris: Pillet et Dumoulin, 1880), 332–33, erroneously as by François-Hubert Drouais, Portrait de femme.

“La Vente de San-Donato,” Le Gaulois (March 16, 1880): 1, erroneously as by Drouais, Portrait de la Femme au Chien.

“Échos de Partout,” La Liberté (March 17, 1880): 3, erroneously as by Drouais, Portrait de la Femme au Chien.

[untitled article], L’Entr’acte (March 17, 1880): 3, erroneously as by Drouais, La Femme au Chien.

“Informations,” Le XIXe Siècle (March 17, 1880): 2, erroneously as by Drouais, Portrait de la Femme au Chien.

“Informations et Faits,” Journal Officiel de la République Française 2, no. 77 (March 18, 1880): 3180, erroneously as by Drouais, La Femme au Chien.

“Échos du Jour,” Le Peuple français (March 18, 1880): 2, erroneously as by Drouais, La Femme au Chien.

“The San Donato Sale,” Times (London) (March 18, 1880): 11, erroneously as by F. H. Drouais, Portrait of a Lady, Seated, with a Spaniel on her Knee.

“Article 13: Vente San Donato commencée le 15 mars 1880,” Journal des Amateurs d’Objets d’Art et de Curiosité 24 (May–June 1880): 59, erroneously as by Drouais, Portrait de la Femme au Chien.

“L’Art, Tome xxi [review],” The Nation 31, no. 796 (September 30, 1880): 244.

Paul Leroi, “Le Palais de San Donato et Ses Collection: XV (Suite),” L’Art: Revue Hebdomadaire Illustrée 6, no. 20 (1880): 310.

L’Art: Revue Hebdomadaire Illustrée 6, no. 21 (1880): (repro.), erroneously as by F. H. Drouais, Portrait.

Victor Champier, L’Année Artistique: Beaux-Arts en France et à l’Étranger (Paris: A. Quantin, 1881), 3:365, erroneously by Drouais, La Femme au Chien.

Charles Davis, A Description of the Works of Art Forming the Collection of Alfred de Rothschild, vol. 1 (London: [Chiswick Press], 1884), unpaginated, erroneously as by Drouais, A Portrait of a Lady.

F. G. Stephens, “Mr. Alfred de Rothschild’s Collection,” Art Journal (July 1885): 218.

Jules Guiffrey, “Table des Portraits Exposés aux Salons du Dix-Huitième Siècle jusqu’en 1800,” Nouvelles Archives de l’Art Français, 3rd ser. (Paris: Charavay Frères, 1889), 5:17.

Emile Dacier, Catalogues de Ventes et Livrets de Salons Illustrés par Gabriel de Saint-Aubin (1909; repr. Jacques Laget, Librairie des Arts et Métiers-Éditions, 1993), 2:71, 83, as Mme Freret-Dericour.

Jules Belleudy, J.-S. Duplessis: Peintre du Roi, 1725–1802 (Chartres: Imprimerie Durand, 1913), 26, 305, 322–23, as Mme Freret-Dericourt.

Constance Flower Battersea, Thoughts in Verse (Norwich: Goose and Son, 1920), 8, erroneously as A Portrait by Drouais.

“Exhibition of Masterpieces Honoring Hazel Barker King, Retiring Curator of the Allen Memorial Art Museum,” Supplement, exh. cat., Bulletin (Allen Memorial Art Museum) 9, (June 1952): 130–31, (repro.), erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Portrait of a Lady with a Dog.

French Eighteenth Century Painters: Loan Exhibition for the Benefit of the Education Program of the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, exh. cat. (New York: Wildenstein, 1954), unpaginated, erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Portrait of a Lady Holding a Dog.

“Accessions of American and Canadian Museums, October–December 1953,” Art Quarterly 17, no. 2 (Summer 1954): 184, 186–87, (repro.), erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Portrait of a Lady Holding a Dog.

“Chardin’s Brilliant Contemporaries,” Art News 53, no. 6 (October 1954): 40, (repro.), erroneously as by Drouais.

“The Century of Mozart: January 15 through March 4, 1956,” Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 1, no. 1 (January 1956): 27, erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Lady Holding a Dog.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 102, 110, (repro.), erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Portrait of a Lady Holding a Dog.

Age of Elegance: The Rococo and Its Effect, exh. cat. (Baltimore: Baltimore Museum of Art, 1959), 29, as Portrait of a Lady Holding a Dog.

“Treasures of Kansas City,” Connoisseur 145, no. 584 (April 1960): 123, erroneously as by F. H. Drouais.

Jean Seznec, ed., Diderot Salons (Oxford: Clarendon, 1967), 4:49, as Mme Freret Dericour.

Ralph T. Coe, “The Baroque and Rococo in France and Italy,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 538–39, (repro.) [repr. in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 70–71, (repro.)], erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Portrait of a lady holding a dog.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 136, (repro.), erroneously as by François Hubert Drouais, Portrait of A Lady Holding a Dog.

Pierre Rosenberg, The Age of Louis XV: French Painting 1710–1774, exh. cat. (Toledo, OH: Toledo Museum of Art, 1975), 38, (repro.), as Portrait of Mme Freret-Déricour.

Else Marie Bukdahl, Diderot, Critique d’Art, trans. Jean-Paul Faucher (Copenhagen: Rosenkilde et Bagger, 1980), 1:154, (repro.).

“Those Beguiling Women,” Calendar of Events (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (September 1983): 3–4, (repro.), as Portrait of Mme. Freret-Dericour.

Santina M. Levey, Lace: A History (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1983), (repro.), as Portrait of Madame Freret-Déricour Holding a Dog.

Ellen R. Goheen, The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988), 71, 73–74, (repro.), as Portrait of Mme Freret Dericour.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 193, (repro.), as Portrait of Mme Freret Déricour.

Denis Diderot, Héros et martyrs, ed. Else Marie Bukdahl et al. (Paris: Hermann, 1995), 4:99n283, as Mme Fréret Dericour.

Alan Wintermute and Donald Garstang, The French Portrait, 1550–1850, exh. cat. (New York: Colnaghi, 1996), 56, (repro.), as Madame Freret-Déricour.

Jane Turner, ed., The Dictionary of Art (New York: Grove’s Dictionaries, 1998), 9:399.

Pierre Sanchez and Xavier Seydoux, Les Estampes de “l’Art” (1875–1907) (Paris: l’Echelle de Jacob, 1999), 87.

Images (Norton Museum of Art) 9, no. 3 (January–February 2003): (repro.), as Mme Freret Déricour.

Jean-Paul Chabaud, Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, 1725–1802: biographie (Mazan: Etudes Comtadines, 2003), 28, 124, (repro.).

Pierre Sanchez, Dictionnaire des Artistes Exposant dans les Salons des XVII et XVIIIème Siècles à Paris et en Province, 1673–1800 (Dijon: L’Echelle de Jacob, 2004), 2:607, as Mme Freret Dericour.

“Art Tasting with Julián,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2010): 11, (repro.), as Portrait of Madame Freret Déricour.

Lesley Ellis Miller, Selling Silks: A Merchant’s Sample Book 1764 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 2014), 16, as Portrait of Madame Freret Déricour.

Joanna M. Gohmann, “The Four-Legged Sitter: A Note on the Significance of the Dog in Jean-Marc Nattier’s La Marquise d’Argenson,” Journal of the Walters Art Museum 73 (2018): 97–98, (repro.), https://thewalters.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/jwam_73_04_24_2018.pdf, as Madame Freret Déricour.

Hannah Williams, “Dog,” in Artists’ Things: Rediscovering Lost Property from Eighteenth-Century France, ed. Katie Scott and Hannah Williams (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2024), 106–07, (repro.), as Madame Fréret d’Héricourt and Her Dog, https://www.getty.edu/publications/artists-things/things/dog/.

Xavier Salmon, Joseph-Siffred Duplessis (1725-1802): Le Van Dyck de la France, exh. cat. (Paris: Editions Lienart, forthcoming 2025).