Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.308.5407.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.308.5407.

When François Boucher created this pastel of Venus and Cupid in the early 1750s, his collaboration with Jeanne Antoinette Poisson (1721–64), the Marquise de Pompadour, had attained its zenith. Boucher scholar Jo Hedley has named the period from 1750 to 1759 as the era when Boucher was firmly “Pompadour’s Painter.”1Jo Hedley, François Boucher: Seductive Visions (London: Wallace Collection, 2004), 98. This was a critical time for both painter and Pompadour, when he was elevated at the court of Versailles and she transitioned from being King Louis XV’s powerful paramour, exercising a unique amount of control over his schedule and heart, to his advisor, friend, and the cultural center of aristocratic society, a position she would maintain until her premature death in 1764. Boucher painted three images of her between 1745 and 1759, but her inspiration was not limited to direct portraiture.2See Alexandre Ananoff and Daniel Wildenstein, François Boucher, vols. 1 and 2 (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des Arts, 1976), nos. 475, 521–22. They are in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich; Waddesdon Manor, Aylesbury, UK; and the Wallace Collection, London. The hold she maintained over court culture after leaving the King’s bed, and her patronage of leading artists, ensured that her spirit imbued Rococo depictions like Boucher’s Venus, the goddess of love.

The production of the Nelson-Atkins pastel coincided with Pompadour’s 1749 and 1750 appearances as Venus in two separate pieces by librettist Pierre Laujon and, subsequently, Laujon and composer Pierre La Garde.5The following each have an appendix stating which plays were performed and when: Winston Haverland Kaehler, “The Operatic Repertoire de Madame de Pompadour’s Théâtre des Petits-Cabinets (1747–1753)” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1971); Hourcade, Madame de Pompadour et le théâtre des Cabinets du Roi. Louis XV was thrilled by Pompadour’s creative output and even had a bound volume published of plays performed in the Theater of the Small Apartments from 1748 to 1749. Savill, Everyday Rococo, 94. In her opening stanzas, Venus-Pompadour commanded her chorus to “serve your mother well” in her efforts to attain the title “Queen of the beauties.”6Pierre Laujon, * “Le Matin, ou La Toilette de Vénus; Divertissement en un acte, Représenté en 1749 à Versailles, sur le théâtre des petits appartemen[t]s,” Oeuvres Choisies de P. Laujon, Membre de l’Institut (Paris: Imprimerie de C.-F. Patris, 1811), 3:373–76. Many of Venus-Pompadour’s lines read as unsubtle digs at her court foes, including the First Gentleman of the Chamber, the duc de Richelieu, who chastised her profligate spending on the exclusive theater.7By court standards, Richelieu should have had control over entertainments in the King’s apartments, but he was overruled by Pompadour. His stature was not restored until Pompadour’s death in 1764. Algrant, Madame de Pompadour, 84. From her proscenium, Venus-Pompadour declared: “My rivals seek to win over me: I never had such a desire to please,” to which her lover Mars, god of War (meant to flatter the King, who had recently ceded significant territory in military negotiations), responded, “Are there rivals to fear / With the attractions of Venus?”8Laujon, “Le Matin, ou La Toilette de Vénus,” 3:377–78. Beyond merely entertaining the most powerful figures at Versailles and later at the Château de Bellevue, where Pompadour moved in 1750, the Theater of the Small Apartments was one way in which Pompadour immersed herself in politics via her beauty, talent, charm, and wit. It was not mere attractiveness that enabled Pompadour’s rapid ascent at Versailles, but these attributes are emphasized (or find visual form) in the Nelson-Atkins composition of Venus and in the artist’s other drawings of the subject.

Both Venus’s and Cupid’s flesh tones are more modulated in the Nelson-Atkins pastel than in the Getty picture, eliminating the allover highlights in favor of small touches of white at Cupid’s wingtips. Additionally, Venus’s accoutrements are more developed in the Nelson-Atkins pastel. For example, the flowers at her feet, though still drawn in loose gestural strokes, here take on the look of a lover’s bouquet recently discarded instead of the wild plant climbing up to just below her extended arm in the Getty pastel. The outlines of bodies and cloth in the Nelson-Atkins picture are darker and more defined, and the anatomies of both Venus and Cupid are more naturalistic, although the impossibly pert, tacked-on busts in both pastels, in addition to the identical faces of all Boucher’s Venuses, suggest that the artist worked diligently to perfect and idealize his goddess over multiple sittings. The minute tuft of white highlight at the tip of Venus’s left little finger in the Nelson-Atkins pastel flaunts not only the artist’s fondness for flourishes but also the goddess’s potential to conjure and create beauty, something the Marquise de Pompadour was keen to associate herself with as her time as court ingenue drew to a close.

Fig. 3. Jean Marc Nattier, JeanneAntoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour in the Guise of Diana the Huntress, 1746, oil on canvas, 39 7/8 x 32 1/16 in. (101.3 x 81.5 cm), Château de Versailles, MV 9042. Photo: Gérard Blot. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 3. Jean Marc Nattier, JeanneAntoinette Poisson, Marquise de Pompadour in the Guise of Diana the Huntress, 1746, oil on canvas, 39 7/8 x 32 1/16 in. (101.3 x 81.5 cm), Château de Versailles, MV 9042. Photo: Gérard Blot. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY

Fig. 4. François Boucher, Earth: Vertumnus and Pomona, 1749, oil on canvas, 34 1/4 x 53 5/8 in. (86.9 x 136.2 cm), Columbus Museum of Art, OH, Museum Purchase: Derby Fund. In honor of Elizabeth M. Ross and in recognition of her dedication and service to the Columbus Museum of Art, 1980.027

Fig. 4. François Boucher, Earth: Vertumnus and Pomona, 1749, oil on canvas, 34 1/4 x 53 5/8 in. (86.9 x 136.2 cm), Columbus Museum of Art, OH, Museum Purchase: Derby Fund. In honor of Elizabeth M. Ross and in recognition of her dedication and service to the Columbus Museum of Art, 1980.027

In contrast, the Venuses of the 1750s, created after Pompadour was no longer sharing the King’s bed, are outrightly bold in their sexuality. Unlike Boucher’s portrait of Pompadour as Diana, the Venus pictures do not bear her exact features, granting plausible deniability as to the identity of the woman depicted. Nevertheless, the association between Venus and Pompadour was acknowledged both onstage, as previously noted, and off, as the Marquise herself commissioned images of the goddess of love to decorate her private Château de Bellevue.13The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Boucher, The Toilette of Venus, was initially created for Pompadour’s bath suite at the Château de Bellevue. François Boucher, The Toilette of Venus, 1751, oil on canvas, 42 5/8 x 33 1/2 in. (108.3 x 85.1 cm.), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 20.155.9, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/435739. Xavier Salmon, Madame de Pompadour et les arts, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées nationaux, 2002), 176. For another example that Pompadour commissioned, see François Boucher, The Bath of Venus, 1751, oil on canvas, 42 1/8 x 33 3/8 in. (107 x 84.8 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1943.7.2, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.12200.html.

Notes

-

Jo Hedley, François Boucher: Seductive Visions (London: Wallace Collection, 2004), 98.

-

See Alexandre Ananoff and Daniel Wildenstein, François Boucher, vols. 1 and 2 (Lausanne: Bibliothèque des Arts, 1976), nos. 475, 521–22. They are in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich; Waddesdon Manor, Aylesbury, UK; and the Wallace Collection, London.

-

For a few examples beyond Hedley, see Ian McInnes, Painter, King and Pompadour: François Boucher at the Court of Louis XV (London: Frederick Muller, 1965); Margaret Crosland, Madame de Pompadour: Sex, Culture, and Power (Phoenix Mill, UK: Sutton Publishing, 2000); Evelyne Lever, Madame de Pompadour: A Life, trans. Catherine Temerson (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000); Christine Pevitt Algrant, Madame de Pompadour: Mistress of France (New York: Grove Press, 2002); Colin Jones, Madame de Pompadour: Images of a Mistress, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery Company, 2002); Xavier Salmon, Madame de Pompadour et les arts, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées nationaux, 2002); Penelope Hunter-Stiebl and Philippe Le Leyzour, La Volupté du Goût: La Peinture française au temps de Madame de Pompadour, exh. cat. (Tours: Musée des Beaux-Arts, 2008); Rosalind Savill, Everyday Rococo: Madame de Pompadour and Sèvres Porcelain, vol. 1 (Bracondale, UK: Unicorn Press, 2021).

-

Hedley, François Boucher, 104; Philippe Hourcade, Madame de Pompadour et le théâtre des Cabinets du Roi (Éditions Michel de Maule, 2014), 21.

-

The following each have an appendix stating which plays were performed and when: Winston Haverland Kaehler, “The Operatic Repertoire de Madame de Pompadour’s Théâtre des Petits-Cabinets (1747–1753)” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1971); Hourcade, Madame de Pompadour et le théâtre des Cabinets du Roi. Louis XV was thrilled by Pompadour’s creative output and even had a bound volume published of plays performed in the Theater of the Small Apartments from 1748 to 1749. Savill, Everyday Rococo, 94.

-

Pierre Laujon, “Le Matin, ou La Toilette de Vénus; Divertissement en un acte, Représenté en 1749 à Versailles, sur le théâtre des petits appartemen[t]s,” Oeuvres Choisies de P. Laujon, Membre de l’Institut (Paris: Imprimerie de C.-F. Patris, 1811), 3:373–76.

-

By court standards, Richelieu should have had control over entertainments in the King’s apartments, but he was overruled by Pompadour. His stature was not restored until Pompadour’s death in 1764. Algrant, Madame de Pompadour, 84.

-

Laujon, “Le Matin, ou La Toilette de Vénus,” 3:377–78.

-

Hedley’s discussion of Boucher’s artistic production beginning in 1750 testifies to the artist’s newfound appreciation for Rubens, whose depictions of women were fleshy, curvy, and pink. Hedley, François Boucher, 109.

-

The frequency with which Boucher’s works were replicated makes it difficult to identify which are originals and which are working drawings, counterproofs, or copies. See Regina Shoolman Slatkin, “Some Boucher Drawings and Related Prints,” Master Drawings 10, no. 3 (Autumn 1972): 264–331. Both the Nelson-Atkins and Getty drawings are accepted as original works by the artist. The solid dating of the Getty picture to the early 1750s, confirmed by the drawing’s inscription documenting Boucher’s gift to a “M. Denis” in 1752, supports that the Nelson-Atkins pastel shares a similar date and was produced in the afterglow of Pompadour’s performance as Venus.

-

Hedley, François Boucher, 99.

-

For a 1749 production of Handel’s opera Acis and Galatea, in which Pompadour played Galatea, her dress was described by the head of costuming, Madame Schneider: “Large skirt of white taffeta painted with roses, shells, and water jets, embroidered with silver frieze edged with a green chenille network; corset of soft pink taffeta; large drapery of silver and green with small stripes, with a weave of another water gauze; the mantle and drapery fully lined with white taffeta. The whole outfit is bordered with tassels and strings of pearls part of which has been rented.” Hourcade, Madame de Pompadour et le théâtre des Cabinets du Roi, 1748. There is an informative gouache by Charles-Nicolas (the Younger) Cochin of this production, made in situ, now in the collection of the National Gallery of Canada; it shows that, even playing a water nymph, Pompadour wore a surplus of fabric. Charles-Nicolas (the Younger) Cochin, Marquise de Pompadour in a Scene from “Acis et Galatée,” 1749, gouache over graphite with traces of pen and brown ink on ivory laid paper, with gold-leaf paper borders, sheet: 6 1/2 x 16 1/8 in. (16.5 x 41 cm.); image: 5 11/16 x 15 1/4 in. (14.5 x 38.8 cm.), National Gallery of Canada, 41953, https://www.gallery.ca/collection/artwork/marquise-de-pompadour-in-a-scene-from-acis-et-galatee.

-

The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Boucher, The Toilette of Venus, was initially created for Pompadour’s bath suite at the Château de Bellevue. François Boucher, The Toilette of Venus, 1751, oil on canvas, 42 5/8 x 33 1/2 in. (108.3 x 85.1 cm.), Metropolitan Museum of Art, 20.155.9, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/ 435739. See Salmon, Madame de Pompadour et les arts, 176. For another example that Pompadour commissioned, see François Boucher, The Bath of Venus, 1751, oil on canvas, 42 1/8 x 33 3/8 in. (107 x 84.8 cm), National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1943.7.2, https://www.nga.gov/collection/art-object-page.12200.html.

-

Anya Shulman, “Layers of Fantasy in Francois Boucher’s The Toilette of Venus” (master’s thesis, University of California, Davis, 2022), 11.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Rachel Freeman, “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

MLA:

Freeman, Rachel. “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

Venus with Cupid was a theme François Boucher and his workshop returned to often, and the pastel in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is one of a cohort of drawings that presents Venus, recently disrobed and meeting the viewer’s gaze with a sidelong glance. She stands in contrappostocontrapposto: Italian for “counterpoise.” A term used in the visual arts to describe a figure standing with their weight on one straightened leg while the other leg is more relaxed. The posture shifts the hips and the shoulders in opposite axes. with one hand raised to her ear or cheek while the other holds back billows of drapery. Behind her is a rosebush, and at her side is an oversized Cupid. This entry offers a long-form description that focuses primarily on the paper supports, as these appear to have been assembled prior to media application and may provide insight into other drawings by Boucher.

The paper support is a layering of three papers laminated together, with an unknown adhesive, before media application. In the Nelson-Atkins artwork, the primary support is the paper that bears the pastel and other painting media; the secondary support is the middle sheet; and the tertiary support is the final, or backmost paper. Together the three sheets form a stiff, medium-weight paperboard1Paperboard refers to “stiff and thick ‘paper’ which may range from a ‘card’ of 0.20 mm or 1/125th of an inch or more and vary in composition from pure rag to wood, straw, and other substances having little or no affinity with ‘paper’ beyond the method of manufacture.” See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-Making Terms (Amsterdam: N. V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 208–09. that was ideal for pastelpastel: A type of drawing stick made from finely ground pigments or other colorants (dyes), fillers (often ground chalk), and a small amount of a polysaccharide binder (gum arabic or gum tragacanth). While many artists made their own pastels, during the nineteenth century, pastels were sold as sticks, pointed sticks encased in tightly wound paper wrappers, or as wood encased pencils. Pastels can be applied dry, dampened, or wet, and they can be manipulated with a variety of tools including paper stumps, chamois cloth, brushes, or fingers. Pastel can also be ground and applied as a powder, or mixed with water to form a paste. Pastel is a friable media, meaning that it is powdery or crumbles easily. To overcome this difficulty, artists have used a variety of fixatives to prevent image loss. and other friablefriable: When paint is no longer sufficiently bound. Friable paint often appears powdery or crumbles easily. media.

A survey of paper descriptions for Boucher drawings discloses a wide variety of paper colors, and imagery on some collection websites reveals the presence of laid molds with an assortment of chain-line intervals and laid-line densities.2Handmade laid papers are characterized by the spacing, or density, of the laid lines, which are typically fine and closely aligned, and the distance, or interval, between the lines created by the chain wires of the mold, which hold the laid wires together. Another identifying characteristic imparted by the mold is the watermark. In the case of the Nelson-Atkins Venus and Cupid, all papers are estimated to be handmade on laid-paperlaid paper: One of the two types of paper. Laid papers are machine or handmade papers, formed on a screen with parallel and tightly spaced wires that form "laid lines" which are visible on the sheet. The laid wires are held together by more widely spaced wires called "chain" lines. In handmade papermaking, the chain wires also secured the screen to the ribs of a wooden frame (the frame and wire assembly is referred to as a mold) that was dipped into a vat of paper-making fibers. In the late eighteenth century, there were widespread changes in the laid mold structure, and papers produced prior to this time are distinguishable by an accumulation of fibers along the chain lines. The other type of paper is wove paper. molds, and the visible papers (primary and tertiary supports) are cream to beige in color,3The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated. with the original paper color in the cream tonal range. With magnification, blue and brown fibers appear infrequently and are well mixed with the dominant furnishfurnish: in paper making, furnish refers to the fibers that compose the paper as well as to the mixture of fibers and water that eventually form the paper sheet. of the primary support. While the blue fibers are well beaten, the brown fibers occasionally appear in clumps. The tertiary support paper is composed of a homogeneous furnish. It is impossible to determine the color of the secondary support paper or comment on aspects of the fiber composition.

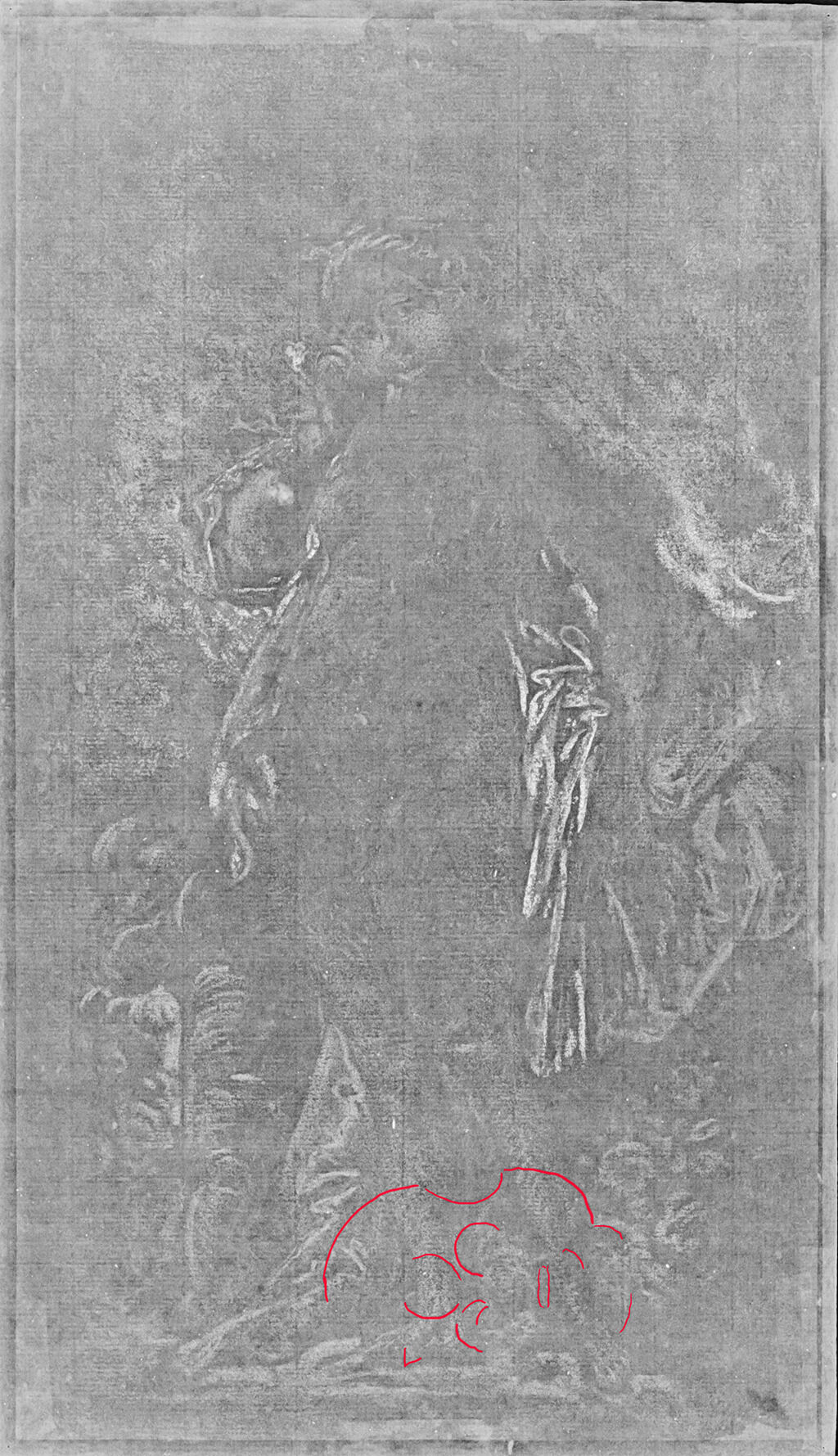

Fig. 7. Radiograph of Venus with Cupid (1750s). The partial watermark, a shield with a fleur-de-lis at the center, is annotated for visibility and appears along the lower edge. The image is reversed as the sharpest capture was attained by placing the digital cassette against the back of the artwork.

Fig. 7. Radiograph of Venus with Cupid (1750s). The partial watermark, a shield with a fleur-de-lis at the center, is annotated for visibility and appears along the lower edge. The image is reversed as the sharpest capture was attained by placing the digital cassette against the back of the artwork.

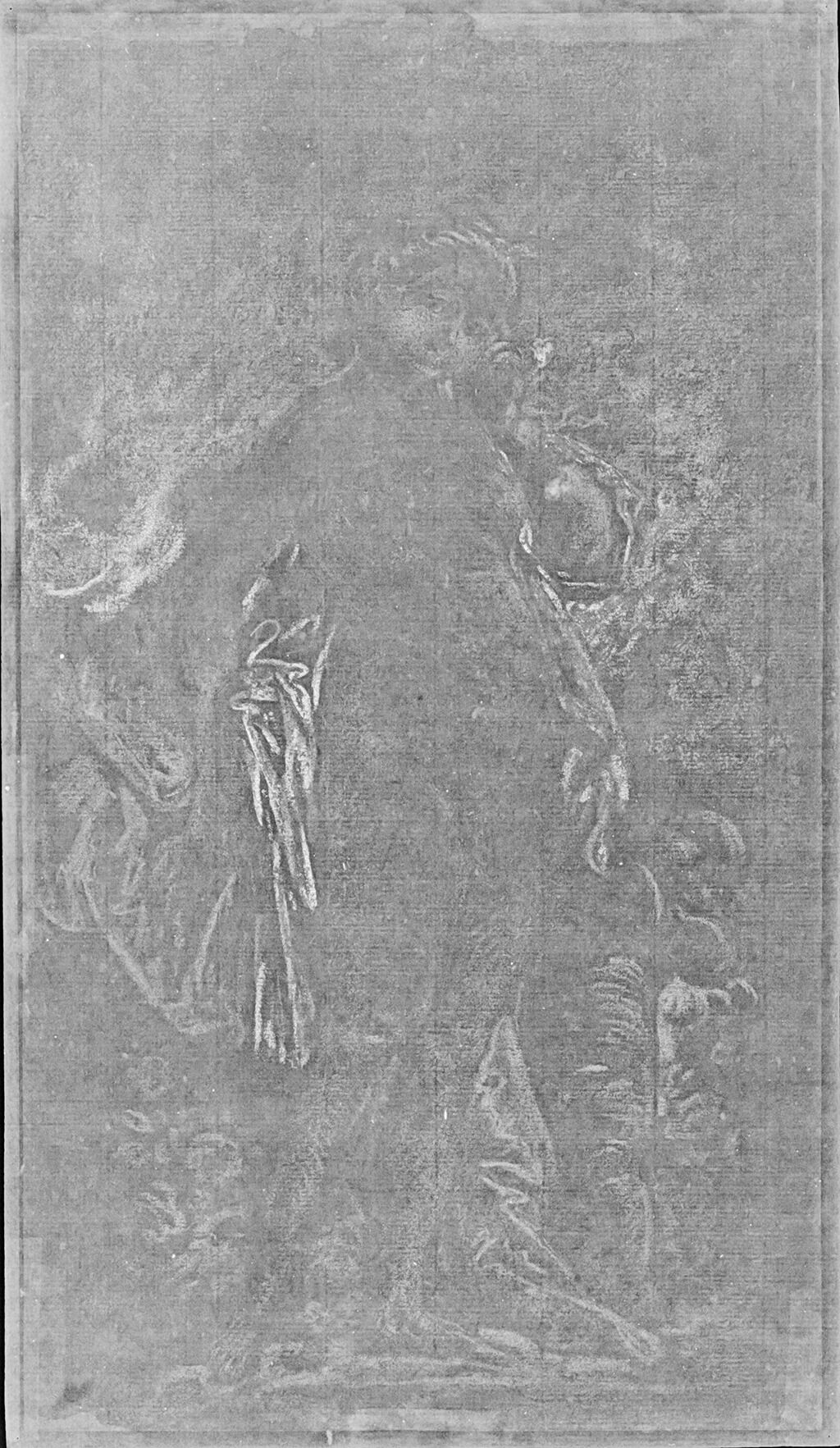

Fig. 8. Transmitted infrared digital photograph of the verso of Venus with Cupid (1750s). The sun or star watermark is annotated for visibility.

Fig. 8. Transmitted infrared digital photograph of the verso of Venus with Cupid (1750s). The sun or star watermark is annotated for visibility.

Boucher’s palette is dominated by blue, pink, an ocher yellow, and white. Vine charcoalvine or willow charcoal: Long, thin charcoal sticks created by burning grape vines or willow twigs in a low carbon environment. Vine and willow charcoal produce brown to black shades. With magnification, the pastel particles often have a splintered appearance and display a characteristic sparkle. appears in both the underdrawing and for shading or detailed work in the final stages of the composition. Red is applied sparingly. During the early stages of composition, Boucher focused on the figures, rounding the forms with lightly applied ochers and touches of pink white. Tiny points of blue are present in the eyes and along Venus’s chin. Blue and charcoal are intermingled to add volume to the right side of her body. Cupid’s round figure is depicted predominantly with yellow ocher, white, and charcoal. The next step in the composition process appears to have been the drapery. Boucher used white, pink, and touches of ocher in the drapery that is either uppermost or closest to Venus’s body. Tiny strokes of red appear in the shadows. The underlayers of drapery are shades of blue and blue blended with white or pink. The roses are pink and white over charcoal hatching, with the leaves indicated in green and the curves of the petals and other foliage reinforced with thin lines of charcoal. There is no evidence of a fixativefixative: An adhesive or varnish that is applied to the surface of powdery media (pastel, chalk, charcoal, or graphite pencil) to prevent smudging or smearing. Fixatives may be applied during the composition process, so that new layers of media can be added without disturbing the underlayers, or after the artwork is complete. Historic fixatives include natural resins, vegetable gums or starches, animal or fish glues, casein, egg white, and a variety of other materials. In the nineteenth century, cellulose nitrate and other early synthetic polymers were available, and in the twentieth century, acrylics and polyvinyl co-polymers were included in fixative solutions. Until the early twentieth century, when methods for containing pressurized gasses were developed and disposable spray cans became common, the fixative could be spattered over the paper with a brush or applied with an atomizer (also called a blow-pipe or mouth sprayer). or similar coating, and the artwork is unsigned.

For the most part, Boucher used pointed pastel sticks for media application; however, he employed the broadside of a blue pastel to tone the background. The pastel is applied so that it does not completely obliterate the color of the paper, which the artist utilized as a mid-tone and to emphasize Venus’s fair skin and hair. Two reds are present: the most common is a warm color and was frequently used in shading. The other red is cooler and is blended with white in the drapery and highlights the blush in Venus’s cheeks, nipples, and labia majora. In radiographsX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. taken to identify watermarks, even lightly applied white media is readable as white, radio-opaque masses (Fig. 9).6See x-radiograph digital capture, no. 575.3, NAMA conservation file, 66-16. The digital x-radiograph was captured in 2022 under the following conditions: 10 kV, 5mAs, and 3.5 seconds. This indicates that a metal, likely white leadlead white: The most widely used white pigment from Roman times until well into the industrial period, it consists of cerussite and/or hydrocerussite, mineral names for neutral lead carbonate and basic lead carbonate, respectively. Plumbonacrite, another basic lead carbonate with proportionately less carbonate than hydrocerussite, can sometimes be found, as well. The whitest forms used in painting were historically produced by inducing lead metal to corrode in the presence of vinegar fumes., was a component of the pastel stick.

The primary support was cut down after the image was completed. The thin, dark ink line around the perimeter of the image is applied over the powdery media. The wider ruled line is drawn on a paper attached to the secondary support and, almost seamlessly, abutted against the primary support. There are several graphite pencil inscriptions on the back of the artwork. These are in a modern hand and refer to catalogue or provenance information (see provenance section below). A brown ink line in the lower right corner appears to be the remains of a line of script that was removed when the paper was cut down (Fig. 10).

Notes

-

Paperboard refers to “stiff and thick ‘paper’ which may range from a ‘card’ of 0.20 mm or 1/125th of an inch or more and vary in composition from pure rag to wood, straw, and other substances having little or no affinity with ‘paper’ beyond the method of manufacture.” See E. J. Labarre, A Dictionary of Paper and Paper-Making Terms (Amsterdam: N. V. Swets and Zeitlinger, 1937), 208–09.

-

Handmade laid papers are characterized by the spacing, or density, of the laid lines, which are typically fine and closely aligned, and the distance, or interval, between the lines created by the chain wires of the mold which hold the laid wires together. Another identifying characteristic imparted by the mold is the watermark.

-

The description of paper color, texture, and thickness follows the standard set forth in Elizabeth Lunning and Roy Perkinson, The Print Council of America Paper Sample Book: A Practical Guide to the Description of Paper (Boston: Print Council of America, 1996), unpaginated.

-

Although it is impossible to verify, it is likely that the primary and secondary supports were adhered together with the mold side of the papers facing away from each other. In a series of radiographs, taken to document the watermarks on the primary and secondary supports, the clearest images of the watermark on the secondary support where captured when the digital cassette was placed on the back of the artwork (see Fig. 7).

-

See x-radiograph digital capture, no. 575.4, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 66-16. The digital x-radiograph was captured in 2022 under the following conditions: 10 kV, 5mAs, and 3.5 seconds.

-

See x-radiograph digital capture, no. 575.3, Nelson-Atkins conservation file, 66-16. The digital x-radiograph was captured in 2022 under the following conditions: 10 kV, 5mAs, and 3.5 seconds.

-

See the accompanying curatorial entry by Glynnis Napier Stevenson.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

Possibly François Boucher (1703–70), Paris, by May 30, 1770;

Possibly purchased at his posthumous sale, Tableaux, desseins [sic], estampes, bronzes, terres cuites, laques, porcelaines de différentes sortes, montées et non montées, meubles curieux, bijoux, minéraux, cristallisations, madrepores, coquilles et autres curiosités, qui composent le cabinet de feu M. Boucher, premier peintre du Roi, cette vente se fera au Vieux Louvre, dans l’appartement du défunt Sieur Boucher, Boucher’s apartments, Louvre, Paris, February 18, 1771, lot 382, as Vénus debout, appuyée sur ses vêtemens, accompagnée de l’Amour, dessein [sic] au trois crayons, sur papier bleu, by Pierre Rémy, 1770 [1];

Possibly Pierre Louis Paul Randon de Boisset (1708–76), Paris, by September 28, 1776;

Possibly purchased at his posthumous sale, Tableaux et desseins [sic] précieux des maîtres célèbres des trois écoles, figures de marbres, de bronze et de terre cuite, estampes en feuilles et autres objets du cabinet de feu M. Randon de Boisset, Receveur général des Finances, par P. Rémy, on a joint à ce catalogue celui des vases, colonnes de marbres, porcelaines, des laques, des meubles de Boule et d’autres effets précieux, Chariot, Rémy, Julliot, Paris, March 10, 1777, lot 350, as Deux différentes compositions de Vénus et l’Amour, faites au pastel, by Robert Quesney (d. 1811), 1777–89 [2];

Possibly “Calonne Angelot,” by May 11, 1789 [3];

Possibly sold at his anonymous sale, Une belle collection de tableaux des trois écoles, dessins montés, miniatures, estampes en recueils et en feuilles, marbres, figures de bronzes, belles tables de porphyre rouge et vert du plus beau choix, meubles et autres objets curieux, composant le cabinet de M**** [Calonne Angelot], C. P. Lebrun et Brusley, Paris, May 11–14, 1789, lot 228, as Deux beaux dessins au pastel, représentant Vénus et l’Amour. Ces deux compositions différentes, sont du meilleur temps de ce Maître. Ils viennent de la Collection de M. Randon de Boisset;

With Alexander Barker, London, by March 1841 [4];

Purchased from Barker by Bindon Blood, Esq. (1775–1855), Ennis, County Clare, Ireland, and Edinburgh, as Cupid unrobing Venus, March 1841–55 [5];

Purchased at his posthumous sale, The Very Extensive Collection of Engravings, from the Earliest Period of the Art to the present time, Formed by the Late Bindon Blood, Esq. of Ennis, County Clare, Ireland, Embracing Historical, Sacred and Profane Subjects, Portraits, Landscapes and Compositions, of the Italian, German, Dutch, Flemish, and French Schools, An Extensive Series of Engravings, After the paintings of Rubens, VanDyck [sic] and Others, The Works of Rembrandt and Hollar, The Productions of Wille and Other Engravers, A Large Assemblage of English and Foreign Portraits, Prints to Illustrate the Dictionaries of Pilkington, Strutt, Bryan, etc., Numerous Original Drawings, by the Old Masters, And a Thousand Original Sketches, by the Eminent Artist, Walter Geikie, Capital Portfolios, etc., S. Leigh Sotheby and John Wilkinson, London, July 18–23, 1856, no. 86, as Venus and Cupid, by François Rapilly, 1856 [6];

With Richard H[ans] Zinser, Forest Hills, Queens, NY, stock no. 439, as Venus with Cupid, by March 11, 1966 [7];

Purchased from Zinser by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1966.

NOTES

[1] Rémy (1715/6–97) was a dealer and author of Boucher’s posthumous sale catalogue. According to an annotation in that catalogue, he bought the drawing from this sale.

The early provenances of Boucher’s multiple pastel drawings of a nude, standing Venus are often difficult to differentiate. Boucher’s posthumous sale featured a Standing Venus, Leaning Against Her Clothes, Accompanied by Love, which was a “drawing in three crayons, on blue paper.” Technical analysis by Rachel Freeman, conservator, paper and Asian art, NAMA, has shown that this Boucher drawing does feature multiple colors, but the paper is a cream/beige color rather than blue.

The Albertina Museum’s François Boucher, Venus with Apple and Cupid of 1763 features black and white chalk on blue natural paper colored brown, so the artist did sometimes tone his papers before settling down to draw. See François Boucher, Venus with Apple and Cupid, 1763, black and white chalk, blue natural paper colored brown, 14 1/2 x 8 7/20 in. (36.8 x 21.2 cm), Albertina Museum, Vienna, Inv. Nr. 12131, https://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/?query=search=/record/objectnumbersearch=12131 &showtype=record.

After further discussion with Alastair Laing and Neil Jeffares, it is very likely that the unusual pose of Venus “leaning against her clothes,” as well as the strong potential that catalogue author Pierre Rémy made a mistake in noting the paper color, confirms the early provenance of the Nelson-Atkins Boucher. The works in the 1771 posthumous Boucher sale and the 1777 posthumous Randon de Boisset sale have the same dimensions and descriptions and are likely the same work. According to Laing, “we do not have such a well-matched pair, each with Cupid, as the Randon de Boisset and ‘Calonne Angelot’ sales.” See email thread from Alastair Laing, Boucher expert, and Neil Jeffares, pastel expert, to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Rachel Freeman, Meghan Gray, and Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, begun April 30, 2023, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] Pierre Rémy organized the Randon de Boisset sale in 1777; therefore, it is possible that he inserted the Boucher pastel into the sale, and Randon de Boisset did not own the work at all.

[3] According to the Getty Provenance Index, “There is a good chance that Calonne Angelot was a fictitious name. It appears that most, if not all, of the lots had belonged a short time earlier to the dealers A. J. Lebrun or Langlier. The name appears nowhere other than as an annotation on this catalogue.” “Sale Catalog F-A967,” Getty Provenance Index, Los Angeles.

[4] See inscription on verso of mounting card in graphite in a hand that matches Bindon Blood’s: f/ / Barker [Ane (?)] 1820 / March / 1841. The inscription probably means Blood bought the pastel from (“f/”) Barker for an amount of 1820 in March 1841.

For further corroboration of Blood’s style of inscription and confirmation of Barker selling to Blood in March 1841, see email from Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, to Hugo Chapman, British Museum, London, February 16, 2022, NAMA curatorial files. See also Frits Lugt, Les Marques de Collections de Dessins et d’Estampes (Amsterdam: Vereenigde Drukkerijen, 1921), no. L.3011.

Alexander Barker (1802–73), based in London and Yorkshire, was a collector and dealer who also frequently worked with the Rothschilds. See “Barker, Alexander,” Grove Art Online (2003): http://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T006390.

[5] Bindon Blood was a collector of prints and antique books. He acquired the nickname “the Vampire” for his voracious appetite for these objects at auction.

[6] For buyer’s last name, see annotated sales catalogue from the Philadelphia Museum of Art Library. The Rapilly family were publishers of prints and art publications active on Paris’s Quai Malaquais; François Rapilly (1820–92) was a print dealer attached to the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

[7] See a letter from Richard H[ans] Zinser to Ross Taggart, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, March 4, 1966, NAMA curatorial files, which says, “this pastel was for many years as a loan from the imperial family deposited in this [Albertina’s] Drawing collection. But after the first war, all claims for property of the imperial family, was handed over to them, as well as many of the imperial Crown jewels.”

In 1919, the ownership of Royal Habsburg collection passed from the Habsburgs to the newly founded Republic of Austria. In 1921, the Albertina Museum was created with this collection. However, because there are no identifying marks on this pastel, it is unlikely that the work was owned by Archduke Friedrich, Duke of Teschen. See email from Meghan Gray, NAMA, to Julia Eßl, Albertina Museum, December 12–14, 2018, and Julia Eßl to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, October 12, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

From 1895 until 1919, Archduke Friedrich, Duke of Teschen (1856–1936), owned a collection of prints and drawings that he inherited from his uncle, Archduke Albrecht Friedrich Rudolf Dominik of Austria, Duke of Teschen (1817–95). In 1921, these formed the collection of the Albertina Museum, Vienna.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art did not purchase the pastel until 1966, which the Albertina’s provenance specialist Julia Eßl argues is a long time after the Albertina acquired the Habsburgs’ old collection and other old Habsburg items were sold through the Viennese auctioneer Albert Kende in the early 1930s. However, this does not negate that Zinser may have owned the pastel for a long time. See Julia Eßl, Albertina Museum, to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, October 12, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

The Nelson-Atkins acquired from Zinser a facsimile of Venus with Cupid (1730–70; Albertina Museum, https://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/?query=search=/record/objectnumbersearch=12133 &showtype=record) at the same time as the acquisition of the pastel. There are several other interesting, related works in that collection.

Due diligence has been performed on sales catalogues that contain Boucher works from the 1750s until 1966. Additional care has been taken to research the window from 1933 to 1945. Due to the suggested provenance from the Albertina, we looked at the well-documented sales from Albert Kende Auction House in Vienna in 1933 and the Dorotheum in Vienna in 1941. Neither of these sales, which both featured works formerly in the Habsburg Collections, contained this drawing.

See Kunstmobiliar, Luster, Uhren, Bronzen, kunstgewerbliche Gegenstände usw. aus der Louis-XVI., Empire– und Biedermeierzeit, ein grosser Savonerie-Teppich aus dem Beginn des XVIII. Jahrhunderts, Teppiche, Gemälde alter Meister aus dem Wiener Palais und den österreichischen Schlössern des Herrn Erzherzog Friedrich (Vienna: Auktionshaus Albert Kende, February 8–10, 1933); and Gemälde des 15. bis 20. Jahrhunderts, Aquarelle, Handzeichnungen, Graphik, Skulpturen, Möbel, Porzellan, Gläser, Arbeiten aus Gold, Silber und Metall, darunter eine Feinzinnsammlung: Versteigerung (Katalog Nr. 467) (Vienna: Dorotheum Kunstabteilung, July 8–10, 1941).

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

François Boucher, Venus and Cupid, about 1750–52, black, white, red, blue, and green chalk, 14 3/4 × 8 3/8 in. (37.5 × 21.3 cm), J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.GB.20.

François Boucher, Standing Girl, 1730–70, black and white chalk, red chalk, green and purple pastel pencil, 13 2/3 x 7 4/5 in. (34.7 x 20 cm), Albertina Museum, Vienna, 12133.

François Boucher, Venus and Cupid with Doves, 1750s, black chalk and pastel, 12 1/5 x 8 1/2 in. (38 x 21.7 cm), Albertina Museum, Vienna, 12132.

François Boucher, Venus with Apple and Cupid, 1763, black and white chalk, blue natural paper colored brown, 14 1/2 x 8 7/20 in. (36.8 x 21.2 cm), Albertina Museum, Vienna, 12131.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

Eighteenth-Century European Drawings from the Collections of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City, and the Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri-Columbia, Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri-Columbia, October 18–November 18, 1979, unnumbered, as Venus and Cupid.

Art in the Age of Revolution, Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, July 14–December 1, 1989, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “François Boucher, Venus with Cupid, 1750s,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.308.2088.

Possibly Pierre Rémy and C. F. Julliot, Catalogue de tableaux et desseins [sic] précieux des maîtres célèbres des trois écoles, figures de marbres, de bronze et de terre cuite, estampes en feuilles et autres objets du cabinet de feu M. Randon de Boisset, Receveur général des Finances, par P. Remy, on a joint à ce catalogue celui des vases, colonnes de marbres, porcelaines, des laques, des meubles de Boule et d’autres effets précieux (Paris: February 27–March 25, 1777), 135, as Deux différentes compositions de Vénus et l’Amour, faites au pastel.

Possibly Tableaux et desseins [sic] précieux des maîtres célèbres des trois écoles, figures de marbres, de bronze et de terre cuite, estampes en feuilles et autres objets du cabinet de feu M. Randon de Boisset, Receveur général des Finances, par P. Rémy, on a joint à ce catalogue celui des vases, colonnes de marbres, porcelaines, des laques, des meubles de Boule et d’autres effets précieux (Paris: Chariot, Rémy, Julliot, March 10, 1777), lot 350, as Deux différentes compositions de Vénus et l’Amour, faites au pastel.

Possibly Catalogue d’une belle collection de tableaux des trois écoles, dessins montés, miniatures, estampes en recueils et en feuilles, marbres, figures de bronzes, belles tables de porphyre rouge et vert du plus beau choix, meubles et autres objets curieux, composant le cabinet de M**** [Calonne Angelot] (Paris: C. P. Lebrun et Brusley, May 11–14, 1789), lot 228, as Deux beaux dessins au pastel, représentant Vénus et l’Amour.

Catalogue of The Very Extensive Collection of Engravings, from the Earliest Period of the Art to the present time, Formed by the Late Bindon Blood, Esq. of Ennis, County Clare, Ireland, Embracing Historical, Sacred and Profane Subjects, Portraits, Landscapes and Compositions, of the Italian, German, Dutch, Flemish and French Schools, An Extensive Series of Engravings, After the paintings of Rubens, VanDyck [sic] and Others, The Works of Rembrandt and Hollar, The Productions of Wille and Other Engravers, A Large Assemblage of English and Foreign Portraits, Prints to Illustrate the Dictionaries of Pilkington, Strutt, Bryan, etc., Numerous Original Drawings, by the Old Masters, And a Thousand Original Sketches, by the Eminent Artist, Walter Geikie, Capital Portfolios, etc. (London: S. Leigh Sotheby and John Wilkinson, July 18–23, 1856), 5, as Venus and Cupid.

Possibly Le Bulletin des beaux-arts: Répertoire des Artistes Français (Paris: Fabré, 1884–85), 53, as Vénus débout.

Henri Frantz, “Paris Letter,” Printseller and Print Collector 1, no. 6 (June 1903): 266, as Love and Venus.

Possibly “Hotel [sic] Drouot,” Le Matin, no. 7014 (May 10, 1903): 2, as Vénus et l’Amour.

Possibly Haldane Macfall and W. G. Menzies, Boucher: The Man, His Times, His Art, and His Significance, 1703–1770 (London: Connoisseur, 1908), 175, as Venus and Cupid.

“Accessions of American and Canadian Museums: January–March, 1966,” Art Quarterly 29, no. 2 (1966): 168, 185, (repro.): as Venus with Cupid.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 186, (repro.), as Venus and Cupid.

Richard G. Baumann and Patricia Crown, Eighteenth-Century European Drawings from the Collections of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City and the Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri-Columbia, exh. cat. (Columbia, MO: Museum of Art and Archaeology, University of Missouri-Columbia, 1979), unpaginated, as Venus with Cupid.

George R. Goldner, European Drawings: Catalogue of the Collections (Malibu, CA: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1988), 1:144.

Roger Ward and Patricia J. Fidler, eds., The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A Handbook of the Collection (New York: Hudson Hills Press, in association with Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 130.

Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastelists; lists before 1800 (London: Unicorn Press, 2006), no. J.173.687, p. 71, as Venus with Cupid.