![]()

Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile,” ca. 1775

| Artist | Etienne Aubry, French, 1745–81 |

| Title | Scene from “Lucile” |

| Object Date | ca. 1775 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Le Fils Fautif, The Offending Son |

| Medium | Oil on paper, mounted on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 13 5/16 × 18 5/16 in. (33.87 × 46.57 cm) |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Allan Katz and Nancy Cohn, 2022.5 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.303.5407.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.303.5407.

This oil sketch by Etienne Aubry of a pair of young lovers in distress is by one of the eighteenth century’s leading genre painters. However, questions surrounding its attribution have intrigued scholars from the moment it appeared on the market in 1985. There has been little scholarship on Aubry overall, making any definite conclusions difficult.1A Sorbonne dissertation, which remains difficult to access, sought to create the first catalogue raisonné of Aubry’s works. See Caroline Fossey, “Etienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781” (PhD diss., Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989). Other Aubry studies have analyzed his take on the socially important issue of wet nursing, which was under debate during the French Enlightenment and is also at issue in Marmontel’s Lucile. See Patricia R. Ivinski et al., Farewell to the Wet Nurse: Etienne Aubry and Images of Breast-Feeding in Eighteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1998). Aubry is considered a genre painter for his interest in moralizing dramas. See Richard Rand, “The Intimate Interior in Eighteenth-Century French Genre Painting,” Antiques Magazine 152, no. 3 (September 1997): 324; Emma Barker, “Putting the Viewer in the Frame: Greuze as Sentimentalist,” Studies in the History of Art 72 (2007): 105–27; and Kristel Smentek, “Sex, Sentiment, and Speculation: The Market for Genre Prints on the Eve of the French Revolution,” Studies in the History of Art 72 (2007): 220–43. At one point, a label attached to a former frame suggested that this was the work of Aubry’s contemporary Etienne Théaulon (1730–80), though there was little to support this assertion.2One Hundred Drawings and Watercolours Dated from the 16th Century to the Present Day (London: Stephen Ongpin Fine Art and Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, 2013), 10. Ahead of the Nelson-Atkins’s acquisition of the painting, the dealer Derek Johns, who had once purchased it, affirmed that the late Greuze scholar Anita Brookner had attributed the painting to Aubry.3Derek Johns, London, to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, January 21, 2022, NAMA curatorial file. Johns purchased the sketch jointly with his business partners Philip Harari and Colnaghi Gallery in 1985. Brookner was an expert in the work of Jean-Baptiste Greuze, the best-known genre painter of his era. Her knowledge of Greuze extended to a keen understanding of Aubry’s œuvre as well. Johns also drew the museum’s attention to two pencil sketches on the verso (Fig. 1), which are no longer visible after relininglining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive..4Johns to Marcereau DeGalan, January 21, 2022. The relining may have been done while the painting was with Johns between 1985 and 1996. These drawings point to the centrality of the young woman’s emotions and reflect the artist’s desire to perfect his composition. The painted sketch on the front of the canvas softens the firm lines of the pencil drawings, heightening the drama and sentimentality of the work in a way that sharp edges could not. The drawings also reveal the extent to which Aubry developed this subject, even if he never produced a related finished canvas for the prestigious SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward..5Aubry, who died at age thirty-six, had a very short Salon career, spanning only the 1770s.

Lucile opens with the titular character excitedly readying for her wedding day to her fiancé Dorval in her father Timante’s home. Chrisman-Campbell has confirmed the wedding-centric aspect of the Nelson-Atkins picture, noting the figure of the marchande de modesmarchande de modes: A vendor who supplied women’s fashion accessories, such as trimmings to decorate caps and shawls. in the doorway, easy to identify by the bandbox under her arm.8Chrisman-Campbell to Stevenson, March 8, 2023. The translation “milliner,” which in modern times suggests hat-making, does not do this occupation justice. In the eighteenth century, a marchande de modes made bespoke gowns even more spectacular with individually selected gloves, lace, and other trimmings, as well as hats. This line of work was immortalized in many contemporaneous paintings and prints, most famously in François Boucher (1703–70)’s The Milliner (Fig. 2). In Boucher’s work, the marchande sits rather ignominiously on the floor as her well-heeled client looks through the available accessories in the bandbox.

The marchande is being rushed out of the room after Lucile’s pre-nuptial preparations are interrupted by Blaise, the widower of Lucile’s wet nurse, who reveals the shocking family secret that Lucile was switched at birth.10David Charlton, “Lucile,” Grove Music Online, December 1, 1992, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.O005009. The practice of sending infants to nurses in the countryside was a subject of debate during the Enlightenment. It inspired treatises by thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–78) and canvases like Aubry’s pro–wet-nurse composition, First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (32-167) and Jean-Baptiste Greuze’s The Nursemaids (31-61), which shows a more negative association with this practice.11For an in-depth look at the issue of wet nursing in eighteenth-century French society and painting, see Ivinski et al., Farewell to the Wet Nurse. As the wet nurse’s dishonesty sets in motion the comedy of errors in Lucile, this play offers another, more lighthearted, take on the issue. To emphasize the point that this wedding day has not started in the best way, the earthenware tureen in the middle of the table at center is ajar. Broken crockery was a common metaphor for sexual impropriety in eighteenth-century genre scenes, but this piece’s lid is simply askew, and the viewer knows that all is easily put right.12P. J. Vinken, “Some Observations on the Symbolism of the Broken Pot in Art and Literature,” American Imago 15, no. 2 (1958): 149–74.

Aubry painted two scenes that allow the status of the Fonroses to contrast with that of Adélaïde, her family, and their rustic home. For example, the elderly woman in both compositions, probably the maid Julie, wears a shawl and a bonnet much like Countess Fonrose’s costume, though Julie’s shawl is black, not white, and her bonnet does not have fine silk ribbons like the Countess’s does. Lucile, like The Shepherdess of the Alps, is a class-mixing comedy that lightly ribs the elite for their adherence to superficial rules of dress and status. Lucile’s fiancé, Dorval, wears several expensive items, like a gray laced coat and red heels, but collapses at the first sign of difficulty.15Chrisman-Campbell identifies the chicness of the young man’s clothing but also emphasizes that none of it goes together. See Chrisman-Campbell to Stevenson, March 8, 2023. Perhaps this is meant to show his immaturity or the limitations of a theater’s costume department. The heroines of both plays prove themselves worthy brides, perhaps better than their hapless suitors deserve, via the contents of their characters.

Notes:

-

A Sorbonne dissertation, which remains difficult to access, sought to create the first catalogue raisonné of Aubry’s works. See Caroline Fossey, “Etienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781” (PhD diss., Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989). Other Aubry studies have analyzed his take on the socially important issue of wet nursing, which was under debate during the French Enlightenment and is also at issue in Marmontel’s Lucile. See Patricia R. Ivinski et al., Farewell to the Wet Nurse: Etienne Aubry and Images of Breast-Feeding in Eighteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1998). Aubry is considered a genre painter for his interest in moralizing dramas. See Richard Rand, “The Intimate Interior in Eighteenth-Century French Genre Painting,” Antiques Magazine 152, no. 3 (September 1997): 324; Emma Barker, “Putting the Viewer in the Frame: Greuze as Sentimentalist,” Studies in the History of Art 72 (2007): 105–27; and Kristel Smentek, “Sex, Sentiment, and Speculation: The Market for Genre Prints on the Eve of the French Revolution,” Studies in the History of Art 72 (2007): 220–43.

-

One Hundred Drawings and Watercolours Dated from the 16th Century to the Present Day (London: Stephen Ongpin Fine Art and Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, 2013), 10.

-

Derek Johns, London, to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, January 21, 2022, NAMA curatorial file. Johns purchased the sketch jointly with his business partners Philip Harari and Colnaghi Gallery in 1985. Brookner was an expert in the work of Jean-Baptiste Greuze, the best-known genre painter of his era. Her knowledge of Greuze extended to a keen understanding of Aubry’s œuvre as well.

-

Johns to Marcereau DeGalan, January 21, 2022. The relining may have been done while the painting was with Johns between 1985 and 1996.

-

Aubry, who died at age thirty-six, had a very short Salon career, spanning only the 1770s.

-

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell to Glynnis Napier Stevenson, NAMA, March 8, 2023, NAMA curatorial file.

-

Jean-François Marmontel and André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry, Lucile: Comédie en un acte, melée d’ariettes, représentée pour la première fois par les Comédiens italiens ordinaires du roi, le 5 janvier 1769 (Besançon: Chez Fantet, 1769).

-

Chrisman-Campbell to Stevenson, March 8, 2023.

-

Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, Fashion Victims: Dress at the Court of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 78, 80.

-

David Charlton, “Lucile,” Grove Music Online, December 1, 1992, https://doi.org

/10.1093 ./gmo /9781561592630 .article .O005009 -

For an in-depth look at the issue of wet nursing in eighteenth-century French society and painting, see Ivinski et al., Farewell to the Wet Nurse.

-

P. J. Vinken, “Some Observations on the Symbolism of the Broken Pot in Art and Literature,” American Imago 15, no. 2 (1958): 149–74.

-

Aubry regularly populates his canvases with recycled characters. The little boy with the drum, who does not appear in the Lucile cast list, nonetheless appears in the Nelson-Atkins picture and another Aubry of 1775, Paternal Love, at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham, UK.

-

Jean-François Marmontel, The Shepherdess of the Alps: A Very Interesting, Pathetic, and Moral History (Glasgow: The Booksellers, 1840), 4.

-

Chrisman-Campbell identifies the chicness of the young man’s clothing but also emphasizes that none of it goes together. See Chrisman-Campbell to Stevenson, March 8, 2023. Perhaps this is meant to show his immaturity or the limitations of a theater’s costume department.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Sophia Boosalis, “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile,” ca. 1775,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.303.2088.

MLA:

Boosalis, Sophia. “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile,” ca. 1775,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.303.2088.

The painted study, Scene from “Lucile,” was executed on a sheet of lightly textured laid paperlaid paper: One of the two types of paper. Laid papers are machine or handmade papers, formed on a screen with parallel and tightly spaced wires that form "laid lines" which are visible on the sheet. The laid wires are held together by more widely spaced wires called "chain" lines. In handmade papermaking, the chain wires also secured the screen to the ribs of a wooden frame (the frame and wire assembly is referred to as a mold) that was dipped into a vat of paper-making fibers. In the late eighteenth century, there were widespread changes in the laid mold structure, and papers produced prior to this time are distinguishable by an accumulation of fibers along the chain lines. The other type of paper is wove paper. that was later lined to a paper interleaf and stretched canvas.1An archival photograph of the painting reveals the presence of the two pencil sketches on the verso. See the accompanying catalogue entry by Glynnis Napier Stevenson. Now concealed, a pencil sketch of two women, one facing frontally and the other in profile, exists on the reverse of the paper (Fig. 1).2The frontally facing woman was rendered with loose, circular, continuous lines that suggest a quick, gestural approach. Conversely, the profile figure is more carefully executed, featuring subtle shading and noticeable variation in line density. Transmitted infrared (IR) photographytransmitted infrared (IR) photography: An examination technique whereby the light source is placed on one side of the artwork while an electronic infrared imager or IR-modified digital camera placed on the opposite side captures the IR that is transmitted. This form of IR photography can be used to detect characteristics of the artist’s paint application, underlying compositions, artist changes, or inscriptions now covered by a lining canvas. revealed that the sketch was executed with the sheet in a vertical orientation. Etienne Aubry later flipped the sheet over, rotated it 90 degrees clockwise, and repurposed it to paint the horizontal format of Scene from “Lucile.”

The sketch was drawn on the mold side of the paper, where it provided slightly better grip for the friablefriable: When paint is no longer sufficiently bound. Friable paint often appears powdery or crumbles easily. media. In contrast, laid and chain lines are barely visible in the oil sketch, as the artist preferred the felt side of the sheet for its smoother surface.3Rachel Freeman and Mary Schafer, February 22, 2022, examination report, NAMA conservation file, no. 2022.5., 4The texture of the paper support was later reduced through the application of preparatory layers. The paper was originally part of a larger sheet and appears to have been trimmed after the painting was completed; on one side, the drawn bonnet of the female has been cropped, while on the other, the oil sketch extends to the sheet’s edges. No watermarkwatermark: An identifying mark in a paper sheet which is created by tying wires to the papermaking mold. Watermarks are most easily viewed with transmitted light; however, some can be read with raking light. is present.

Aubry applied a thin white groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. across the entire sheet to reduce surface texture and prevent the oil paint from sinking into the paper fibers (Fig. 6). The x-radiographX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image. reveals that the lead-containing ground was rapidly applied using streaky, zigzagging, and overlapping brushstrokes (Fig. 7).5See digital radiographs, no. 604, September 11, 2025, NAMA conservation file, no. 2022.5.

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the little boy’s hair in Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775), showing the paper support (1) and white ground (2)

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the little boy’s hair in Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775), showing the paper support (1) and white ground (2)

Fig. 7. X-radiograph of Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775), showing short streaky brushstrokes of the lead-containing ground

Fig. 7. X-radiograph of Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775), showing short streaky brushstrokes of the lead-containing ground

The compositional layout for the Scene from “Lucile” was sketched in pencil on top of the ground, with traces of the underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint. still visible beneath the thin paint layers (Fig. 8). Loose, continuous lines establish the placement of figures and objects, reflecting a quick approach reminiscent of the frontally facing woman sketched on the reverse of the paper. Multiple overlapping lines roughly define the shape of the figures’ faces, limbs, and garments, along with a few marks for the placement of facial features (Fig. 9). Aubry may have applied a brownish yellow imprimaturaimprimatura: A thin layer of paint applied over the ground layer to establish an overall tonality.; however, this warmer tonality could relate to the presence of a yellowed natural-resin varnish.6No paint samples were taken for analysis during this technical study.

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the underdrawing in Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775). Black arrows indicate the visible pencil marks below the paint layers.

Fig. 8. Photomicrograph of the underdrawing in Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775). Black arrows indicate the visible pencil marks below the paint layers.

Fig. 9. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775)

Fig. 9. Reflected infrared digital photograph of Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775)

With efficiency, Aubry painted the scene using a combination of thin washwash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent.-like applications and opaque paint applied wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color.. The background was laid in with brown washes that extend into some of the figures and objects. Darker brown brushstrokes define architectural details, particularly on the left side of the painting, while the addition of opaque gray scumblesscumble: A thin layer of opaque or semi-opaque paint that partially covers and modifies the underlying paint. suggest the right wall and floor.

Figures and objects were initially blocked in with transparent washes that remain visible in the shadows, while highlights were created using lead-white mixtures applied wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface.. With a fine 1/16-inch brush, the folds in the fabric and minor details such as buttons were defined with brown paint. Faces were rendered economically. The artist made use of the dark preparatory washes for areas of shadow and indicated features with opaque strokes of beige and touches of pink to model skin and convey subtle complexion. The three central figures received the greatest attention, while secondary figures were executed more quickly, with thinner paint and minimal detail.

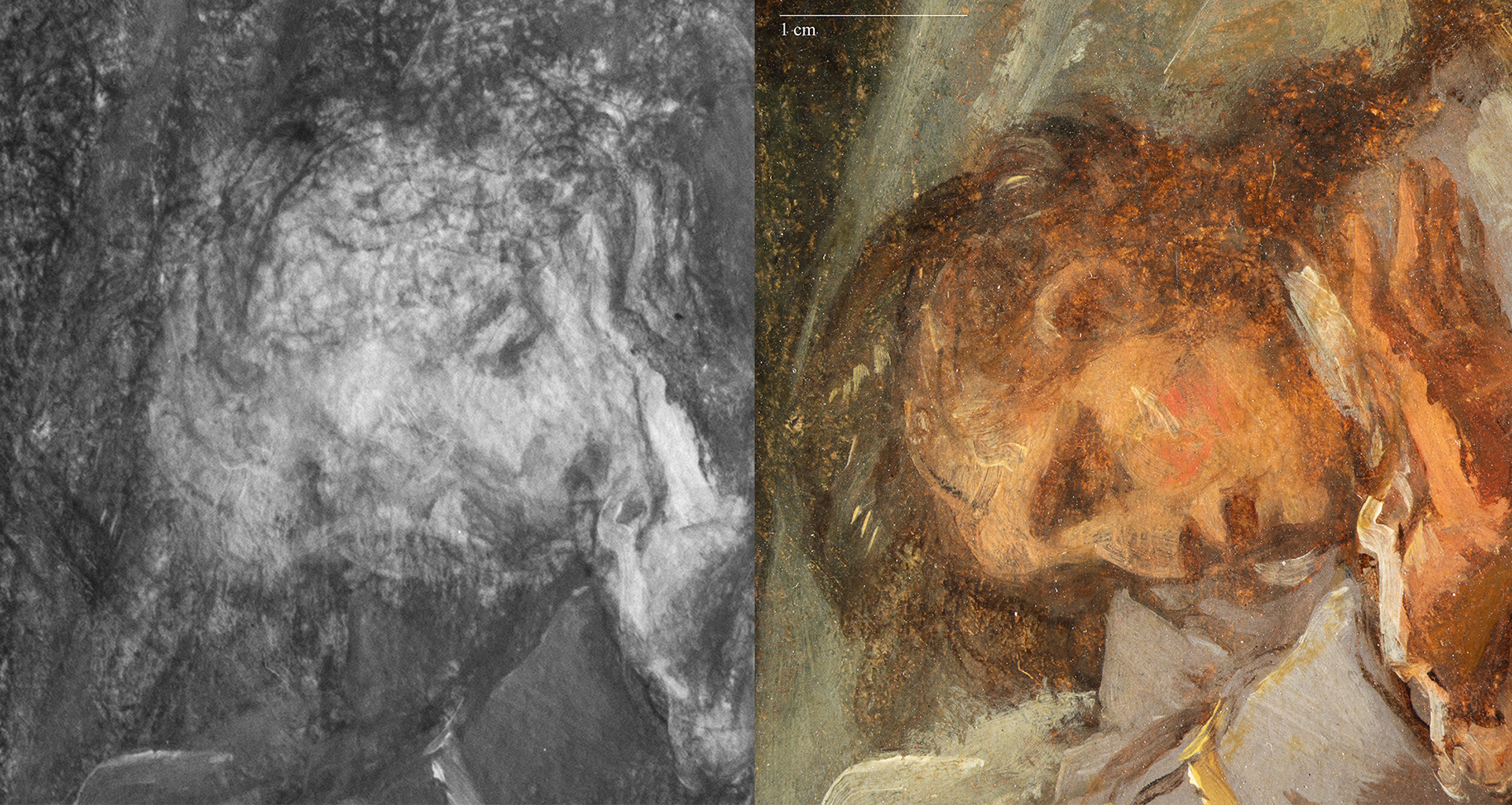

The painted composition closely follows the underdrawing with one notable exception in the central male figure. Infrared (IR) photographyinfrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700-1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film. shows that the man’s head was initially placed at a higher angle, his hand concealing his face from the two women (Fig. 10). During the painting process, the artist repositioned the head, tilting it more steeply downward and intensifying his dramatic collapse to the floor.

Fig. 10. Details of the man’s face, Scenes from “Lucile,” (ca. 1775), reflected infrared digital photograph (left) and a photomicrograph (right)

Fig. 10. Details of the man’s face, Scenes from “Lucile,” (ca. 1775), reflected infrared digital photograph (left) and a photomicrograph (right)

Fig. 11. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775)

Fig. 11. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, Scene from “Lucile” (ca. 1775)

The Scene from “Lucile” underwent at least two treatment campaigns prior to its acquisition by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in 2022. The painted sketch was glue-paste lined onto a white wove paperwove paper: One of the two types of paper. Wove papers may be either machine or handmade, and are produced from molds that have a woven wire mesh. The weave of the mesh can be so tight that it produces no visible pattern within the paper sheet, and often wove papers have a smoother surface than laid papers. Wove papers were developed during the mid-eighteenth century, but did not come into widespread use until later. The other type of paper is laid paper. interleaf and a tightly woven plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas and attached to a modern stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging..7See the accompanying provenance by Glynnis Napier Stevenson. Retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. is primarily concentrated in the abradedabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. brown background, with additional inpainting in the darker paint passages of the figures. Under ultraviolet radiationultraviolet (UV) radiation: A segment of the electromagnetic spectrum, just beyond the sensitivity of the human eye, with wavelengths ranging from 100–400 nanometers. For a description of its use in the study of art objects, see ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence., two distinct retouching campaigns appear dark: the earlier features broader, lighter strokes applied with a larger brush, while the more recent consists of smaller, darker dabs that, in some areas, overlap the earlier campaign (Fig. 11). In addition, the surface is coated with two varnish layers, likely a natural resin and a synthetic. Brown gum tape was applied along the outer edges of the support after the second campaign of retouching. A more recent varnish removal test is visible in the lower left corner of the composition.

Notes

-

An archival photograph of the painting reveals the presence of the two pencil sketches on the verso. See the accompanying catalogue entry by Glynnis Napier Stevenson.

-

The frontally facing woman was rendered with loose, circular, continuous lines that suggest a quick, gestural approach. Conversely, the profile figure is more carefully executed, featuring subtle shading and noticeable variation in line density.

-

Rachel Freeman and Mary Schafer, February 22, 2022, examination report, NAMA conservation file, no. 2022.5.

-

The texture of the paper support was later reduced through the application of preparatory layers.

-

See digital radiographs, no. 604, September 11, 2025, NAMA conservation file, no. 2022.5.

-

No paint samples were taken for analysis during this technical study.

-

See the accompanying provenance by Glynnis Napier Stevenson.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

Private collection, France;

Purchased from Ader Picard Tajan, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, as by François Guérin, by Philip Harari and Derek Johns, Ltd., London, in half shares with P. and D. Colnaghi, London, 1985–May 10, 1996 [1];

Purchased from Colnaghi by Allan J. Katz (b. 1947) and Nancy E. Cohn (b. 1947), Kansas City, MO, May 10, 1996–February 24, 2022 [2];

Given by Allan Katz and Nancy Cohn to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2022.

Notes:

[1] See email from Derek Johns, Derek Johns Fine Art, to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, January 21, 2022, NAMA curatorial files. Johns acquired the painting from a sale in Paris (no catalogue/date), although he recalled that it was 1985. At the time, the painting was attributed to François Guerin. The late Greuze scholar, Anita Brookner (Courtauld), subsequently attributed the picture to Aubry.

Stephen Ongpin, who worked for P. and D. Colnaghi, New York, from 1986 to 1996, and then at the firm’s London gallery from 1996 to 2006, remembered that the sale was at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris and operated by the auctioneers Ader-Picard-Tajan, although he thought it was between 1993 and 1995. See email from Ongpin to Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, NAMA, December 15, 2021, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] Cohn and Katz offered the painting for sale at Old Master Paintings Part II, Christie’s, New York, January 31, 2013, lot 286, as by Etienne Aubry, Le Fils Fautif; and at Old Master Drawings, Sotheby’s, New York, January 30, 2019, lot 74, as by Etienne Aubry, The Offending Son (Le Fils Fautif), but it failed to sell both times.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

Étienne Aubry, The Shepherdess of the Alps, 1775, oil on canvas, 20 x 20 1/2 in. (50.8 x 62.2 cm.), Detroit Institute of Arts, Founders Society Purchase with funds from Mr. and Mrs. Edgar B. Whitcomb, 48.12.

Robert Delaunay, after Étienne Aubry, An episode in “Sheperdess of the Alps” by Jean-François Marmontel: Fonrose disguised as a shepherd begs forgiveness from his father M. de Fonrose, while the seated goatherd Adelaide de Sevile is embraced by Madame de Fonrose, 1786, etching, 12 11/16 x 13 7/8 in. (32.2 x 35.2 cm), Wellcome Collection, London, 28851i.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

One Hundred Drawings and Watercolours dated from the 16th century to the present day, Stephen Ongpin Fine Art, Riverwide House, London, Winter 2013–2014, no. 8, as by Etienne Aubry, The Offending Son (Le fils fautif).

References

Citation

Chicago:

Glynnis Napier Stevenson, “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

MLA:

Stevenson, Glynnis Napier. “Etienne Aubry, Scene from “Lucile”, ca. 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.303.4033.

One Hundred Drawings and Watercolours dated from the 16th century to the present day, exh. cat. (London: Stephen Ongpin Fine Art and Guy Peppiatt Fine Art, Ltd., Winter 2013), 10, (repro.), as by Etienne Aubry, The Offending Son (Le fils fautif).

Old Master Paintings Part II: Property from the Château de Dampierre, France; Property from the collection of Charles and Nonie de Limur, San Francisco; Property from the collection of Nancy Cohn and Allan Katz (New York: Christie’s, January 31, 2013), 80, as by Étienne Aubry, Le fils fautif.

Old Master Drawings (New York: Sotheby’s, January 30, 2019), l18, as by Étienne Aubry, The Offending Son (Le fils fautif).