![]()

Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775

| Artist | Etienne Aubry, French, 1745–81 |

| Title | The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship |

| Object Date | 1773 or 1775 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Deux Époux, allant voir un de leurs enfans en nourrice, font embrasser le petit nourriçon par son frère aîné; La première leçon d’amitié fraternelle; Visite à la nourrice |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 31 1/4 x 38 1/2 in. (79.4 x 97.8 cm) |

| Signature | Signed and dated lower right: Et. aubry, 177[5 or 3] |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 32-167 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Richard Rand, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.5407.

MLA:

Rand, Richard. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.5407.

Etienne Aubry was one of the more accomplished genre painters who emerged at the Paris SalonsSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. in the 1770s, filling the void left by Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725–1805), who had withdrawn from publicly exhibiting his work during that decade, and by Jean Siméon Chardin (1699–1779), who had turned his focus back to painting still lifes. Aubry first came to notice as a portraitist, the category in which he was accepted by the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture in 1771, but he aspired to be a painter of multifigure pictures. He achieved this first, and most successfully, with scenes of daily life, but he later turned to historical subjects. In 1777, at the urging of the comte d’Angivillier (1730–1810)—the influential directeur des batîments (in effect, the minister of culture) and one of Aubry’s principal patrons—he traveled to Italy, but his attempts at history painting met with little enthusiasm. He died in Paris soon after his return from Rome, at the age of thirty-six.

Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, in her foundational article on Aubry published in 1925, considered The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship to be “one of the most ambitious genre paintings painted by Aubry.”1“Un des plus ambitieux tableaux de genre qu’ait peints Aubry”; Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, “Quelques tableaux de genre inédits par Étienne Aubry (1745–81),” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 67 (1925): 82. The only systematic modern study of Aubry’s oeuvre is Caroline Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi 1745–1781” (PhD. diss., Université de Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989). He first exhibited it at the Paris Salon of 1777 with the description, “Two spouses, going to see one of their children at the wet nurse’s, encourage his older brother to embrace the little nurseling.”2“Deux Époux, allant voir un de leurs enfans [sic] en nourrice, font embrasser le petit nourriçon par son frère aîné”; Explication des Peintures, Sculptures et Gravures, de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale (hereafter Salon livret), exh. cat. (Paris: Herissant, 1777), 25. The rustic interior, with its rough stone floor and bare wall devoid of decoration, suggests the humble circumstances of the young nursemaid, who sits to the left of center, holding her young charge in her lap. The infant leans toward his older brother, who stands on the tips of his toes as he reaches up to kiss his sibling. He is encouraged by his mother, who gently presses him forward. His father, seated comfortably at the left, gazes upon this touching scene, as do two figures standing at the right: a younger man—probably the nursemaid’s husband—and a kindly older woman, who leans on the back of a chair. Aubry orchestrated the picture with considerable skill, arranging his figures with care and employing an array of eloquent gestures and expressions to convey the nuances of his little drama, techniques inspired by the works of Greuze. At his death, Aubry was recognized for bringing a level of sophistication to these pictures of daily life, which “he succeeded in making interesting by the pathos of his scenes, the moving predicaments of his actors, and virtuous subjects . . . and by a pleasing contrast of passions, feelings, and characters.”3“En intéressant par le pathétique des scenes, par la situation touchante des acteurs, par des sujets vertueux, . . . par une opposition heureusement contrastée des passions de sentimens [sic] et de caractères”; “Notice sur M. Aubry, peintre,” 1781, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 61, no.1903, p. 2–3.

Unlike Greuze, Aubry, as one art critic wrote in 1777, “has the merit of often bringing together in his pictures city folk with those from the countryside.”4“M. Aubry a le mérite de réunir ordinairement dans ses Tableaux les gens de la ville avec ceux de la campagne”; Jugement d’une demoiselle de quatorze ans sur le Sallon de 1777 (Paris: Quillau,1777), 16, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes,vol. 10, no. 178. In The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, he distinguished between the aristocratic parents and their rural counterparts—what the artist’s viewers would have recognized as representing the Second EstateThree Estates, the: In pre-Revolutionary France (before 1789), society was divided into three classes. The First Estate was composed of the clergy and those who directed the Catholic church. They could impose a ten-percent tax (tithe). The Second Estate comprised the nobility and members of the Royal family, who did not have to pay taxes. The Third Estate encompassed the rest of society, upon whom all taxes fell, from the poorest people to the upper-middle classes. and the Third Estate, respectively—through specificities of clothing, facial and body types, and poses and gestures.5As pointed out in Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi,” 480. These distinctions allowed viewers to appreciate the class dynamics in play, enhancing the underlying conflict enacted before their eyes. The infant’s birth parents have come, it is clear, from an entirely different world: the well-to-do father, seated at left, is dressed at the height of fashion in a red velvet coat trimmed in gold, knee breeches (culottes), and a tricorne hat displayed jauntily on his head, his long hair pulled back by a blue ribbon. He appears at ease, gazing with some amusement at his children’s encounter. His wife, wearing a magnificent white satin dress that swirls around her in billowing folds, with her hair pulled up in elaborate curls, leans toward her sons with a slightly anxious look crossing her face. This elegant couple anchors the composition, filling the modest surroundings with confidence and casual authority. By contrast, the rustic pair observing the scene at the right expresses in their poses and slight remove a deference befitting their social standing, even as their kindly expressions suggest the emotional bonds they have developed for their young charge.

At the center of the scene, Aubry placed the nursemaid herself, holding the little boy out to receive his brother’s embrace. Unlike the sour nurses in Greuze’s The Nursemaids, this young woman appears healthy and maternal, well suited for her job. She embodies contemporaneous notions of the ideal wet nurse, as described in 1765 in the Encyclopédie (a general encyclopedia published in France between 1751 and 1772): “The qualifications of a good wet nurse are usually considered to be her age, the amount of time since she has given birth, her physical condition, especially that of her breasts, the quality of her milk, and, finally, her morals.”6“Les conditions necessaires à une bonne nourrice se tirent ordinairement de son âge, du tems [sic] qu’elle est accouchée,de la constitution de son corps, particulierement de ses mamelles,de la nature de son lait, & enfin de ses mœurs”; “Nourrice,” in Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, ed. Denis Diderot (1765; repr. Stuttgart:Friedrich Frommann Verlag, 1966), 11:260. Aubry shows her in simple clothes, wearing a modest bonnet, and with one breast and nipple exposed, in pointed contrast to the elaborately draped and coiffed mother; the nursemaid represents “nature” rather than the world of “culture” signified by the high-born husband and wife. This dichotomy is also conveyed by the two brothers—one sporting an elegant white suit and black chapeau; the other nearly naked—and by the visual rhyme between the father’s walking stick and the long handle of the copper pot at the lower right. The latter forms part of a beautifully realized group of onions, cabbages, and cooking utensils; they are drawn straight from the repertoire of Chardin, another key influence on Aubry’s art. This still life in the corner of the painting suggests a well-stocked larder and the simple, healthy country diet of the nursemaid and her family.

The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship was only one of several genre scenes Aubry submitted to the Salon of 1777 (he also exhibited a Portrait of an Artist and “numerous small pictures” that have not been identified). It may have been painted several years earlier—the last numeral of the date on the Nelson-Atkins’ picture appears to be a “3” or a “5” rather than the “6” that is often assumed.7Aubry’s submissions to the Salon of 1777 are “no. 127. Portrait d’un Artiste” and “no. 128. Plusieurs petits Tableaux, sous le même numéro”; Salon livret, 25. Fossey has identified two of the latter as L’Heureuse mère and L’Enfant effrayé; Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi,” 26. Fossey also catalogued two drawings for the composition, both lost; Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi,” nos. 103 and 104. See report of examination by Nathan Sutton, NAMA conservation intern, November 2, 2009, NAMA curatorial files. It was not unusual at the time for artists to exhibit works made at an earlier date. At the Salon, the few critics who mentioned Aubry were generally admiring of his large family drama The Interrupted Wedding (private collection)8MMI, exh. cat. (London: Hall and Knight, 2001), 154–57; Emma Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2005), 226–29, fig. 87. but more critical of his other works. One of them wrote, “M. Aubry makes scenes of daily life: there is a certain merit in his works, but he is far too mannered . . . ; all in all, he would do better to devote himself to portraiture.”9“M. Aubry fera donc le genre familier: il y a quelque mérite dans ses productions; mais il est beaucoup trop maniéré . . . ; au surplus, il fera mieux de se livrer au portrait”; La Prêtresse, ou Nouvelle Manière de Prédire ce qui est arrivé (Rome: les Marchands de Nouveautés, 1777), 17, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 189, p. 17. The Nelson-Atkins painting received mixed reviews: one writer thought that “its vigor, its execution, and its expression are all admirable,”10“Les deux époux . . . forment aussi en Tableau où la vigeur, l’effet & l’expression se font également admirer”; Lettres Pittoresques, à l’Occasion des Tableaux Exposés au Sallon, en 1777 (Paris: P. F. Gueffier, [1777]), 22, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 190, p. 22. while another complained of its “badly painted” colors that were “laid on too thick.”11“Mal peint: les couleurs en sont épaisses & plaquées”; Les Tableaux du Louvre, Où Il n’y a Pas Le Sens Commun, Histoire Véritable (Paris: Cailleau, 1777), 17, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 186. The subject seems to have particularly disturbed the latter critic: “I will say nothing about it, because attitudes that give rise to a practice so contrary to nature as that of entrusting one’s children to a hired woman must not be very natural and, consequently, cannot touch the heart of a rational man.”12“Quant au sujet, je n’en dirai rien, parce que des sentimens [sic] qui tiennent à un usage aussi peu dans la Nature que celui de confier ses enfans [sic] à une femme mercenaire, ne doivent pas être fort naturels, & par conséquent ne peuvent toucher un home raisonnable”; Les Tableaux du Louvre, Où Il n’y a Pas Le Sens Commun, Histoire Véritable, 17. This was becoming a common refrain among reform-minded thinkers during these years, who condemned wet nursing in lieu of mothers breastfeeding their own children.13For a good analysis, see Bernadette Fort, “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing,” in Anja Müller, Fashioning Childhood in the Eighteenth Century (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006), 117–34. The writer in the Encyclopédie, for example, criticized the practice: “Aside from the usual rapport between the child and the mother, the latter is much more likely to take tender care of her child than a hired woman who is only motivated by the salary she receives, which is often very modest. One must conclude that a child’s mother, even if she is not as good a wet nurse, is still preferable to a stranger.”14“Indépendamment du rapport ordinaire du tempérament de l’enfant à celui de la mere [sic], celle-ci est bien plus propre à prendre un tendre soin de son enfant, qu’une femme empruntée qui n’est animée que par la récompense d’un loyer mercenaire, souvent fort modique. Concluons que la mere [sic] d’un enfant, quoique moins bonne nourrice, est encore préférable à une étrangere [sic]”; “Nourrice,” in Diderot, Encyclopédie, 261.

Notes

-

“Un des plus ambitieux tableaux de genre qu’ait peints Aubry”; Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, “Quelques tableaux de genre inédits par Étienne Aubry (1745–1781),” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 67 (1925): 82. The only systematic modern study of Aubry’s oeuvre is Caroline Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi 1745–1781” ( Université de Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989).

-

“Deux Époux, allant voir un de leurs enfans [sic] en nourrice, font embrasser le petit nourriçon par son frère aîné”; Explication des Peintures, Sculptures et Gravures, de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale (hereafter Salon livret), exh. cat. (Paris: Herissant, 1777), 25.

-

“En intéressant par le pathétique des scenes, par la situation touchante des acteurs, par des sujets vertueux, . . . par une opposition heureusement contrastée des passions de sentimens [sic] et de caractères”; “Notice sur M. Aubry, peintre,” 1781, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 61, no. 1903, p. 2–3.

-

“M. Aubry a le mérite de réunir ordinairement dans ses Tableaux les gens de la ville avec ceux de la campagne”; Jugement d’une demoiselle de quatorze ans sur le Sallon de 1777 (Paris: Quillau, 1777), 16, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 178.

-

As pointed out in Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi,” 480.

-

“Les conditions necessaires à une bonne nourrice se tirent ordinairement de son âge, du tems [sic] qu’elle est accouchée, de la constitution de son corps, particulierement de ses mamelles, de la nature de son lait, & enfin de ses mœurs”; “Nourrice,” in Encyclopédie, ou Dictionnaire Raisonné des Sciences, des Arts et des Métiers, ed. Denis Diderot (1765; repr. Stuttgart: Friedrich Frommann Verlag, 1966), 11:260.

-

Aubry’s submissions to the Salon of 1777 are “no. 127. Portrait d’un Artiste” and “no. 128. Plusieurs petits Tableaux, sous le même numéro”; Salon livret, 25. Fossey has identified two of the latter as L’Heureuse mère and L’Enfant effrayé; Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi,” 26. Fossey also catalogued two drawings for the composition, both lost; Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi,” nos. 103 and 104, pp. 474–76. See report of examination by Nathan Sutton, NAMA conservation intern, November 2, 2009, NAMA curatorial files.

-

MMI, exh. cat. (London: Hall and Knight, 2001), 154–57; Emma Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2005), 226–29, fig. 87.

-

“M. Aubry fera donc le genre familier: il y a quelque mérite dans ses productions; mais il est beaucoup trop maniéré . . . ; au surplus, il fera mieux de se livrer au portrait”; La Prêtresse, ou Nouvelle Manière de Prédire ce qui est arrivé (Rome: les Marchands de Nouveautés, 1777), 17, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 189, p. 17.

-

“Les deux époux . . . forment aussi en Tableau où la vigeur, l’effet & l’expression se font également admirer”; Lettres Pittoresques, à l’Occasion des Tableaux Exposés au Sallon, en 1777 (Paris: P. F. Gueffier, [1777]), 22, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 190, p. 22.

-

“Mal peint: les couleurs en sont épaisses & plaquées”; Les Tableaux du Louvre, Où Il n’y a Pas Le Sens Commun, Histoire Véritable (Paris: Cailleau, 1777), 17, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 186.

-

“Quant au sujet, je n’en dirai rien, parce que des sentimens [sic] qui tiennent à un usage aussi peu dans la Nature que celui de confier ses enfans [sic] à une femme mercenaire, ne doivent pas être fort naturels, & par conséquent ne peuvent toucher un home raisonnable”; Les Tableaux du Louvre, Où Il n’y a Pas Le Sens Commun, Histoire Véritable, 17.

-

For a good analysis, see Bernadette Fort, “Greuze and the Ideology of Infant Nursing,” in Anja Müller, Fashioning Childhood in the Eighteenth Century (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2006), 117–34.

-

“Indépendamment du rapport ordinaire du tempérament de l’enfant à celui de la mere [sic], celle-ci est bien plus propre à prendre un tendre soin de son enfant, qu’une femme empruntée qui n’est animée que par la récompense d’un loyer mercenaire, souvent fort modique. Concluons que la mere [sic] d’un enfant, quoique moins bonne nourrice, est encore préférable à une étrangere [sic]”; “Nourrice,” in Diderot, Encyclopédie, 261.

-

See, for example, Fossey, “Étienne Aubry, Peintre du Roi,” 480.

-

Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment, 192.

-

“All are united in the warmth of this charming moment of the first filial embrace, which serves as a metaphor for the idea of universal brotherhood which flourished in this period”; Eric M. Zafran, The Rococo Age: French Masterpieces of the Eighteenth Century, exh. cat. (Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 1983), 119. See also Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment, 192, with the fair point that such meaning could have been posthumously applied to the engraving: “Some such didactic and even symbolic significance seems to underlie the title that Aubry’s composition acquired when the print after it [sic] appeared in 1787.”

-

“Notice sur Jacques-Augustin de Silvestre,” in François Léandre Regnault-Delalande, Catalogue Raisonné d’Objets d’Arts du Cabinet de Feu M. de Silvestre, ci-devant Chevalier de l’Ordre de Saint-Michel, et Maitre à Dessiner des Enfans de France (Paris: [François Léandre Regnault-Delalande], 1810), iii–viii. The works by Aubry are catalogued under nos. 1 (Coriolanus), 2 (First Lesson), and 166–72 (drawings). The title given for the Kansas City painting, Les Adieux d’un villageois et de sa femme au nourrisson que le père et la mère leur retirent, has caused confusion with the Williamstown Farewell to the Wet Nurse (Fig. 1), but the dimensions recorded (29.6 x 39 pouces [inches]) match the Kansas City painting, and the painting is described as the one engraved by Delaunay under the title La première Leçon d’Amitié fraternelle.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Sophia Boosalis, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” technical entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.2088.

MLA:

Boosalis, Sophia. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” technical entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2026. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.2088.

Etienne Aubry executed The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship on a plain-weaveplain weave: A basic textile weave in which one weft thread alternates over and under the warp threads. Often this structure consists of one thread in each direction, but threads can be doubled (basket weave) or tripled to create more complex plain weave. Plain weave is sometimes called tabby weave. canvas that was linedlining: A procedure used to reinforce a weakened canvas that involves adhering a second fabric support using adhesive, most often a glue-paste mixture, wax, or synthetic adhesive. prior to its acquisition by the Nelson-Atkins in 1932. Information about the original canvas is limited, as the tacking marginstacking margins: The outer edges of canvas that wrap around and are attached to the stretcher or strainer with tacks or staples. See also tacking edge. have been removed and the outer edges are obscured by retouchingretouching: Paint application by a conservator or restorer to cover losses and unify the original composition. Retouching is an aspect of conservation treatment that is aesthetic in nature and that differs from more limited procedures undertaken solely to stabilize original material. Sometimes referred to as inpainting or retouch. and brown tape. However, the genregenre: Figural scenes of ordinary people engaged in the activities of everyday life. painting appears to be close to its original dimensions, as cuspingcusping: A scalloped pattern along the canvas edges that relates to how the canvas was stretched. Primary cusping reveals where tacks secured the canvas to the support while the ground layer was applied. Secondary cusping can form when a pre-primed canvas is re-stretched by the artist prior to painting. is visible along all edges in the radiographX-ray radiography (also referred to as x-radiography or radiography): Radiography is an examination tool analogous to the use of X-rays in medicine whereby denser components of a painted composition can be recorded as an inverted shadow image cast on film or a digital X-ray imaging plate from a source such as an X-ray tube. The method has been used for more than a century and is most effective with dense pigments incorporating metallic elements such as lead or zinc. It can reveal artist changes, underlying compositions, and information concerning the artwork’s construction and condition. The resulting image is called an x-radiograph or radiograph. It differs from the uses of X-ray spectrometry in being dependent on the density of the paint to absorb X-rays before they reach the film or image plate and being non-specific as to which elements are responsible for the resulting shadow image..1Digital radiograph, no. 605, NAMA conservation file, 32-167. The canvas was prepared with a thin, light-gray groundground layer: An opaque preparatory layer applied to the support, either commercially or by the artist, to prevent absorption of the paint into the canvas or panel. See also priming layer. that is now visible due to extensive abrasionabrasion: A loss of surface material due to rubbing, scraping, frequent touching, or inexpert solvent cleaning. throughout the composition and along the craquelurecraquelure: The network or pattern of cracks that develop on a paint surface as it ages..

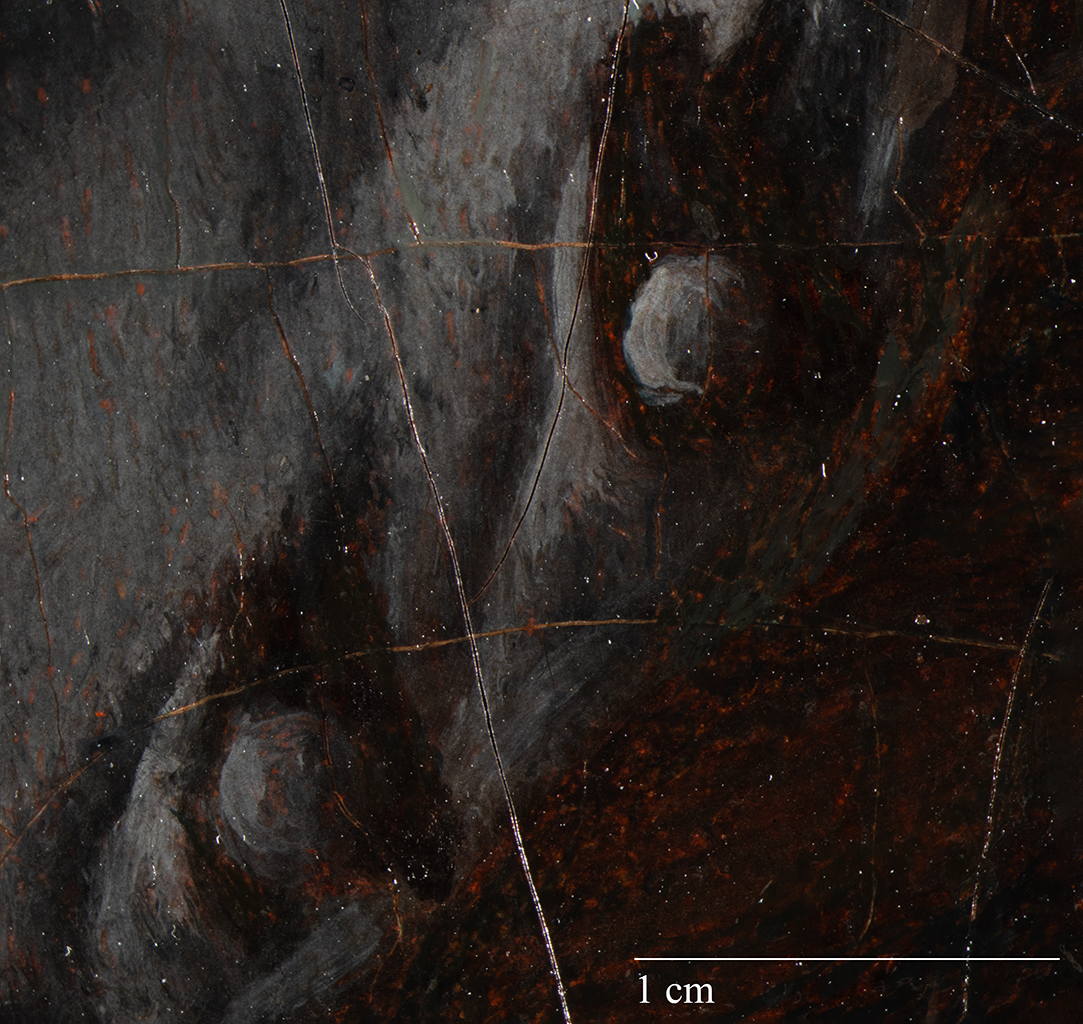

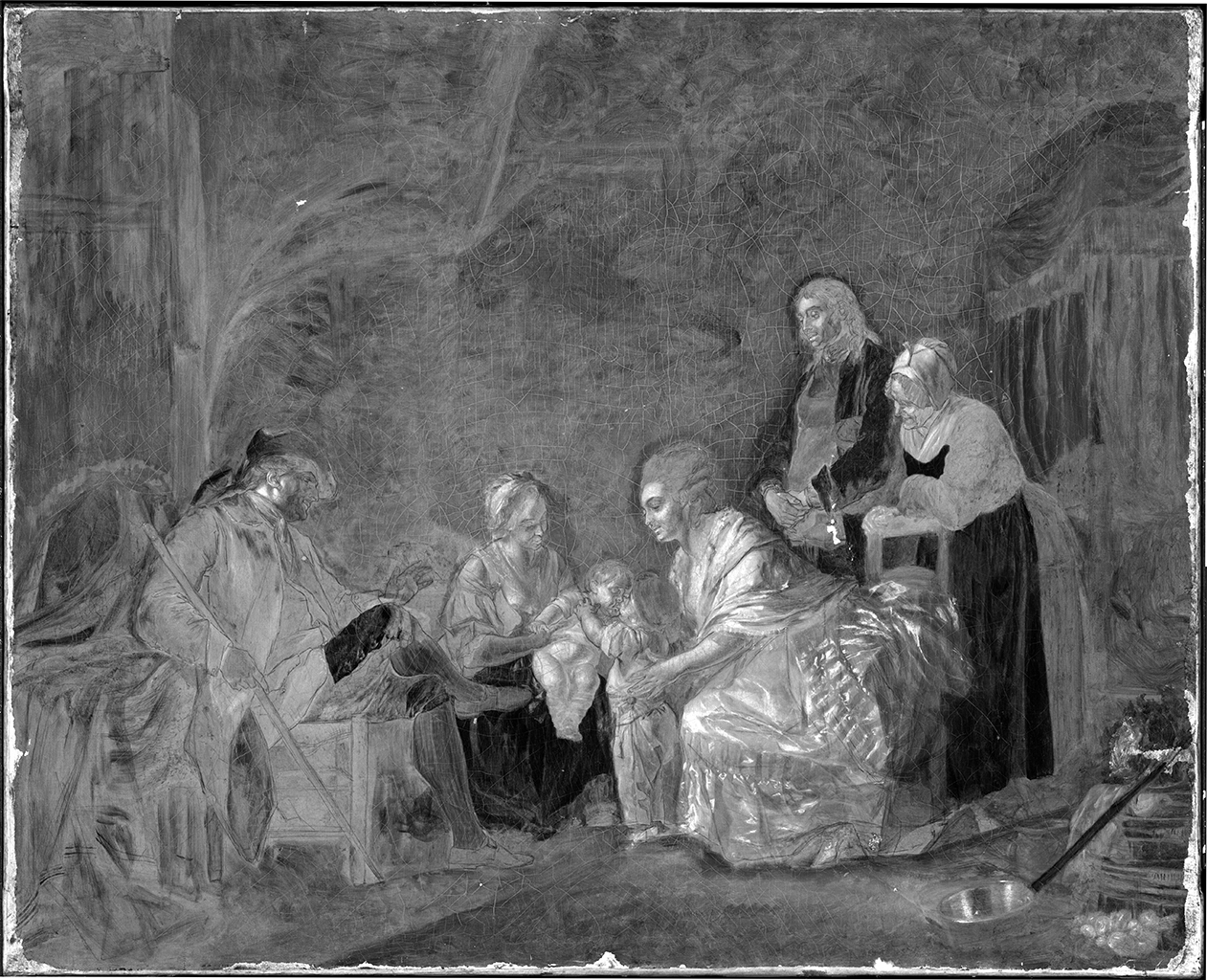

Aubry typically used preparatory studies on paper as a means of developing his compositions,2Etienne Aubry appears to have made preparatory studies on paper prior to painting, making slight refinements to his compositions. For instance, the study Mother and Children (1755–81; Clark Art Institute, https://www.clarkart.edu/ArtPiece/Detail/Mother-and-Children), executed in pen and black ink over pencil, served as a preparatory work for the painting La Mère Heureuse, which was later reproduced in Maurice Blot’s (1753–1818) etching La Bonté Maternelle (1770–1818; Albertina, Vienna, https://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/objects/565058/la-bonte-maternelle). Aubry slightly deviated from the preparatory sketch by altering the mother’s dress, revealing her shoulders and cleavage in the painting. For the painting, see Etienne Aubry, La Mère Heureuse, oil on oval canvas, 21 1/2 x 26 in. (54.7 x 66.1 cm), sold at Christie’s, London, Property from the Collection of the Late Lord Matthews, October 30, 2014, lot 183, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5836696. and Caroline Fossey identified L’Heureuse Famille (The Happy Family) (date and location unknown), a pencil drawing heightened with white chalk, as an early study for the Nelson-Atkins painting, though in a vertical format.3It is not possible to assess how the preparatory drawing L’Heureuse Famille informed the Nelson-Atkins painting. Etienne Aubry, L’Heureuse Famille (The Happy Family), pencil heightened with white chalk on paper, 16 5/16 × 8 11/16 in. (41.5 × 22 cm), private collection, location unknown, cited in Caroline Fossey, “Étienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781” (master’s thesis, Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989), no. 103, p. 474. For further discussion, see the accompanying catalogue entry by Richard Rand. Examination of The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship under the stereomicroscope revealed a rough graphite sketch, traces of which remain visible beneath the thinly painted passages in the figures and surrounding objects (Fig. 3).4Aubry most likely employed a comparable rough sketch, as indicated by hints of graphite lines in Paternal Love (exhibited 1775; Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, England, https://barber.org.uk/etienne-aubry-1745-1781/) and The Shepherdess of the Alps (1775; Detroit Institute of Arts, https://dia.org/collection/shepherdess-alps-33299). The author is grateful to Edith Brown (assistant curator) and Robert Wenley (head of collections and deputy director) at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts for facilitating the examination of Paternal Love on April 30, 2025. Traces of graphite lines are visible beneath the thinly painted areas, roughly outlining the figures’ faces and hands, as well as diagonal lines delineating the cracks in the rough stone floor. The underdrawing is difficult to discern in areas with thicker or more opaque paint; infrared reflectography could potentially reveal the full extent of the underdrawing. The author thanks Grace An (Andrew W. Mellon fellow in painting conservation) at the Detroit Institute of Art (DIA) for sharing the conservation records for The Shepherdess of the Alps. Infrared reflectography (IRR)infrared reflectography (IRR): A form of infrared imaging that exploits the behavior of painting materials at wavelengths beyond those accessible to infrared photography. These advantages sometimes include a continuing increase in the transparency of pigments beyond wavelengths accessible to infrared photography (i.e, beyond 1,000 nanometers), rendering underdrawing more clearly. The resulting image is called an infrared reflectogram. Devices that came into common use in the 1980s such as the infrared vidicon effectively revealed these features but suffered from lack of sharpness and uneven response. Vidicons continue to be used out to 2,200 nanometers but several newer pixelated detectors including indium gallium arsenide and indium antimonide array detectors offer improvements. All of these devices are optimally used with filters constraining their response to those parts of the infrared spectrum that reveal the most within the constraints of the palette used for a given painting. They can be used for transmitted light imaging as well as in reflection. shows an extensive underdrawingunderdrawing: A drawn or painted sketch beneath the paint layer. The underdrawing can be made from dry materials, such as graphite or charcoal, or wet materials, such as ink or paint., with lines defining the contours of the figures and their clothing, including facial features, hands, and hairstyles (Fig. 4). Additional gestural lines roughly indicate the major folds of the garments, particularly in the aristocratic woman.

Fig. 3. Photomicrograph of the elder woman’s head, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775)). Black arrows indicate the presence of the graphite underdrawing.

Fig. 3. Photomicrograph of the elder woman’s head, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775)). Black arrows indicate the presence of the graphite underdrawing.

Fig. 4. Infrared reflectogram captured at 2100 nanometers of The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775)

Fig. 4. Infrared reflectogram captured at 2100 nanometers of The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775)

With the underdrawing in place, Aubry began to underpaintunderpainting: The first applications of paint that begin to block in color and loosely define the compositional elements. Also called ébauche. various parts of the composition, leaving a reservereserve: An area of the composition left unpainted with the intention of inserting a feature at a later stage in the painting process. for the figures. Brown and gray washeswash: An application of thin paint that has been diluted with solvent. further defined architectural elements and created spatial depth in the rustic interior. Aubry then proceeded to apply a light gray underpainting, followed by streaky brushstrokes of pinkish beige, blue, and brown washes to suggest the appearance of cracked stone in the floor. Extensive paint abrasion and retouching make it difficult to determine whether Aubry built up the surrounding background all at once or painted it gradually in concert with the figures. However, the hemline of the noblewomen’s dress and the nobleman’s hat appear to sit on top of the underlying paint, indicating that in these areas the interior was completed before the figures.

The loose, sketchy appearance of the room contrasts with the tightly rendered still life in the right foreground. Using an extremely fine brush, Aubry applied short, overlapping strokes and dabs of opaque paint wet-over-wetwet-over-wet: An oil painting technique which involves drawing a stroke of one color across the wet paint of another color. to capture the play of light across each onion and within the reflective surface of the cooking pot.

Aubry appears to have modeled the faces over a beige underpainting. A light gray wash defines the cool shadows while a peachy pink wash was applied to create warm shadows and the figures’ rosy complexions. Pink, beige, white, and light blue were layered in the highlights of some figures, where the paint was applied wet-over-wet in small, fluid strokes that allowed the colors to blend subtly (Fig. 5). The facial features were constructed with brown tones used for the shadows, followed by pinkish-red paint, and finished with a dark purplish red to define the lips, nostrils, and pupils. Similar colors were used in the hands and arms, where brown and red tones form the shadows and outline the fingers, while the highlights were built up with soft, intermingling strokes of paint applied wet-over-wet.

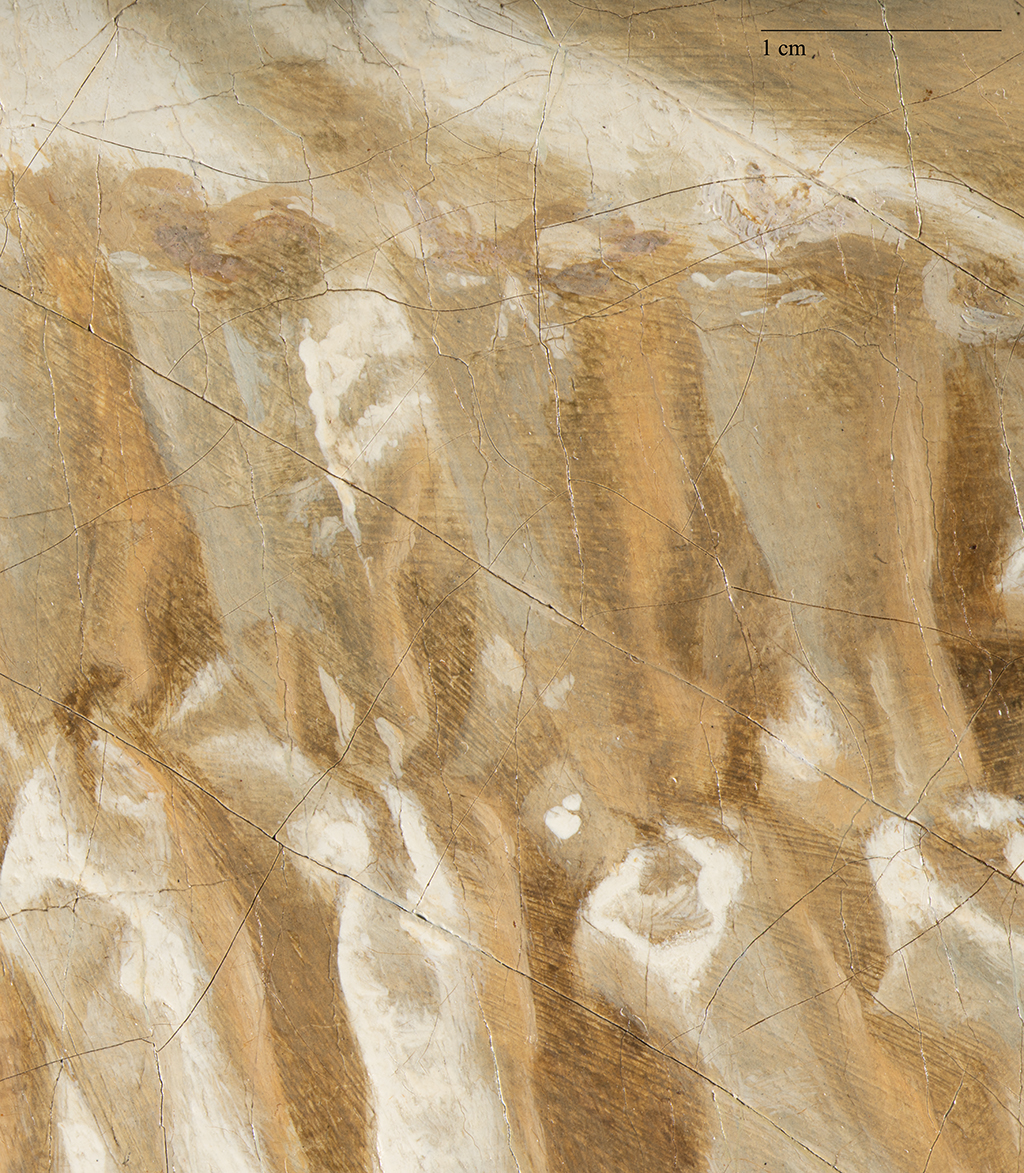

The figures’ clothing was thinly painted with controlled and delicate layering, showing careful attention to the different fabrics and their textures. Aubry appears to have applied washes to various components of the costumes, traces of which remain visible in the shadowed passages. The underpainting ranges from light brown to black, with the exception of a red wash in the nobleman’s velvet attire. Highlights were introduced with thin, fluid paint and wet-into-wetwet-into-wet: An oil painting technique which involves blending of colors on the picture surface. application. Aubry gave more attention to the two central women, whose garments were rendered with greater complexity than those of the surrounding figures. The wet nurse’s clothing is distinctive for its patterned fabrics: streaky, crisscrossing brushstrokes and dabs of white paint define her blue skirt (Fig. 6), while vertical strokes of red, black, and ochre, worked wet-over-wet, create the striped effect of her beige underskirt. The noblewoman’s dress was constructed with greater delicacy and precision. Using an extremely fine brush, Aubry carefully built up fluid layers of gray and beige over streaky brown underpainting to establish warm and cool shadows, adding dabs of white to suggest the shimmering quality of the silk (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the young nursemaid’s skirt in The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775), showing streaky, crisscrossing brushstrokes

Fig. 6. Photomicrograph of the young nursemaid’s skirt in The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775), showing streaky, crisscrossing brushstrokes

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of the noblewoman’s skirt, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775)

Fig. 7. Photomicrograph of the noblewoman’s skirt, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775)

IRR shows that Aubry diverged from the established underdrawing in the folds and contours of the aristocratic woman’s dress and the blanket draped over the bassinet. The older child, who stands on his tiptoes, was originally sketched with his feet flat on the floor in a less-animated greeting.5Email communication with John Twilley, science advisor to the Nelson-Atkins, November 29, 2025. Additionally, the placement of the copper pan in the still life was shifted slightly during the painting process. The greatest departure from the underdrawing is seen in the placement of the nobleman’s proper left hand, originally drawn as an open-palm gesture that partially obscured the cat (Fig. 8). Aubry later repositioned the man’s hand to wrap around his left knee and lowered the jacket cuff, an adjustment conceived early in the execution of the genre painting.

During the painting process, Aubry may have altered the color of the nobleman’s clothing. The man’s velvet trousers appear to have been initially underpainted with red paint like his coat (Fig. 9). Aubry subsequently applied blue paint over this underpainting, leaving traces of the red wash visible along the edges and within the shadows. Due to extensive abrasion of the upper paint layers, it remains uncertain whether Aubry intended to fully obscure the red wash. Nevertheless, the use of such a bright, contrasting underpainting for the trousers appears inconsistent with the construction of the other figures.

Art historian Caroline Fossey first connected La Visite à la Nourrice (The Visit to the Nurse) (Fig. 10), a sepia wash on paper, to the Nelson-Atkins painting in 1989.6Fossey, “Étienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781,” no. 104, pp. 474–76. For the reproduction of this drawing, see the Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, box and folder “Courtauld_032153_Witt_048526 / Aubry, Etienne / 1745–1781, Drawings,” https://photocollections.courtauld.ac.uk/sec-menu/search/detail/8bb1c8c2-7ca3-ccbd-fe49-cdb5e2f76311/media/8639cc93-9543-b156-47a0-09df3e2adfa7. Pentimentipentimento (pl: pentimenti): A change to the composition made by the artist that is visible on the paint surface. Often with time, pentimenti become more visible as the upper layers of paint become more transparent with age. Italian for "repentance" or "a change of mind." observed in The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship confirm that the drawing was made after the painting and possibly served as the model for Nicolas Delaunay’s engraving (Fig. 2).7Aubry produced sepia washes of paintings that were later reproduced as etchings. For example, Das Hirtenmädchen in den Alpenmade (The Shepherd Girl of the Alps, 1775; Albertina, Vienna, https://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/objects/33231/das-hirtenmadchen-in-den-alpen), a sepia wash on paper, relates to the painting The Shepherdess of the Alps (1775; Detroit Institute of Arts) and its engraving by Jean Jacques Leveau (1729–1786) (1774–86; one example is at British Museum, London, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1891-0511-93). There is a slight difference in the face of the noble lady between the sepia wash and the painting. Paul L. Grigaut, “Marmontel’s ‘Shepherdess of the Alps’ in Eighteenth Century Art,” Art Quarterly (Detroit Institute of Arts) 12, no. 1 (Winter 1949): 45. Its composition reflects the final placement of the older child’s feet and the nobleman’s proper left hand, rather than the positions visible in the underdrawing. In addition, the composition was embellished by the inclusion of a jug in the background, an object that also appears in the engraved reproduction.

Fig. 10. Etienne Aubry, La Visite à la Nourrice (The Visit to the Nurse), ca. 1776, sepia wash on paper, 15 1/8 x 18 7/8 in. (39 x 48 cm), unknown location. Photo courtesy of Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC-BY-NC).

Fig. 10. Etienne Aubry, La Visite à la Nourrice (The Visit to the Nurse), ca. 1776, sepia wash on paper, 15 1/8 x 18 7/8 in. (39 x 48 cm), unknown location. Photo courtesy of Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London; Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial (CC-BY-NC).

Fig. 11. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775)

Fig. 11. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence photograph, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775)

The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship was treated at least once prior to the acquisition by the Nelson-Atkins in 1932. The canvas was glue-paste lined, the tacking margins were removed, and a tear was repaired. The varnish was also removed, although an overly strong cleaning solvent caused extensive abrasion and paint loss along the edges of the mechanical cracksmechanical cracks: Cracks, either localized or overall, that form in response to movement or stress..8James Roth, July 1941, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 32-167. More than one distinct set of vertical and horizontal cracksstretcher cracks: Linear cracks or deformations in the painting’s surface that correspond to the inner edges of the underlying stretcher or strainer members. have formed in the center of the canvas, indicating that the painting is no longer supported by its original stretcherstretcher: A wooden structure to which the painting’s canvas is attached. Unlike strainers, stretchers can be expanded slightly at the joints to improve canvas tension and avoid sagging due to humidity changes or aging.. The painting has undergone three treatments while in the Nelson-Atkins collection. Conservator James Roth cleaned and retouched the painting shortly after its acquisition.9Roth, treatment report. It was later consolidated in 1984 to address a few areas of flaking.10Forrest Bailey, February 2, 1984, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 32-167. In 2009, the painting was cleaned and efforts were made to visually reintegrate the pronounced craquelure, losses, and areas of extensive abrasion including in the background, crib, and cat.11Nathan Sutton, August 12, 2010, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 32-167. The extent of the retouching campaign is evident when the painting is examined under ultraviolet (UV) radiationultraviolet (UV) radiation: A segment of the electromagnetic spectrum, just beyond the sensitivity of the human eye, with wavelengths ranging from 100–400 nanometers. For a description of its use in the study of art objects, see ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence. (Fig. 11).

Notes

-

Digital radiograph, no. 605, NAMA conservation file, 32-167.

-

Etienne Aubry appears to have made preparatory studies on paper prior to painting, making slight refinements to his compositions. For instance, the study Mother and Children (1755–81; Clark Art Institute, https://www.clarkart.edu

/ArtPiece ), executed in pen and black ink over pencil, served as a preparatory work for the painting La Mère Heureuse, which was later reproduced in Maurice Blot’s (1753–1818) etching La Bonté Maternelle (1770–1818; Albertina, Vienna, https://sammlungenonline.albertina.at/Detail /Mother -and -Children /objects ). Aubry slightly deviated from the preparatory sketch by altering the mother’s dress, revealing her shoulders and cleavage in the painting. For the painting, see Etienne Aubry, La Mère Heureuse, oil on oval canvas, 21 1/2 x 26 in. (54.7 x 66.1 cm), sold at Christie’s, London, Property from the Collection of the Late Lord Matthews, October 30, 2014, lot 183, https://www.christies.com/565058 /la -bonte -maternelle /en ./lot /lot -5836696 -

It is not possible to assess how the preparatory drawing L’Heureuse Famille informed the Nelson-Atkins painting. Etienne Aubry, L’Heureuse Famille (The Happy Family), pencil heightened with white chalk on paper, 16 5/16 × 8 11/16 in. (41.5 × 22 cm), private collection, location unknown, cited in Caroline Fossey, “Étienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781” (master’s thesis, Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989), no. 103, p. 474. For further discussion, see the accompanying catalogue entry by Richard Rand.

-

Aubry most likely employed a comparable rough sketch, as indicated by hints of graphite lines in Paternal Love (exhibited 1775; Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, England, https://barber.org.uk

/etienne ) and The Shepherdess of the Alps (1775; Detroit Institute of Arts, https://dia.org-aubry -1745 -1781/ /collection ). The author is grateful to Edith Brown (assistant curator) and Robert Wenley (head of collections and deputy director) at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts for facilitating the examination of Paternal Love on April 30, 2025. Traces of graphite lines are visible beneath the thinly painted areas, roughly outlining the figures’ faces and hands, as well as diagonal lines delineating the cracks in the rough stone floor. The underdrawing is difficult to discern in areas with thicker or more opaque paint; infrared reflectography could potentially reveal the full extent of the underdrawing. The author thanks Grace An (Andrew W. Mellon fellow in painting conservation) at the Detroit Institute of Art (DIA) for sharing the conservation records for The Shepherdess of the Alps./shepherdess -alps -33299 -

Email communication with John Twilley, science advisor to the Nelson-Atkins, November 29, 2025.

-

Fossey, “Étienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781,” no. 104, pp. 474–76. For the reproduction of this drawing, see the Witt Library, Courtauld Institute of Art, London, box and folder “Courtauld_032153_Witt_048526 / Aubry, Etienne / 1745–1781, Drawings,” https://photocollections.courtauld.ac.uk/sec-menu/search/detail/8bb1c8c2-7ca3-ccbd-fe49-cdb5e2f76311/media/8639cc93-9543-b156-47a0-09df3e2adfa7.

-

Aubry produced sepia washes of paintings that were later reproduced as etchings. For example, Das Hirtenmädchen in den Alpenmade (The Shepherd Girl of the Alps, 1775; Albertina, Vienna, https://sammlungenonline

.albertina ), a sepia wash on paper, relates to the painting The Shepherdess of the Alps (1775; Detroit Institute of Arts) and its engraving by Jean Jacques Leveau (1729–1786) (1774–86; one example is at British Museum, London, https://www.britishmuseum.org.at /objects /33231 /das -hirtenmadchen -in -den -alpen /collection ). There is a slight difference in the face of the noble lady between the sepia wash and the painting. Paul L. Grigaut, “Marmontel’s ‘Shepherdess of the Alps’ in Eighteenth Century Art,” Art Quarterly (Detroit Institute of Arts) 12, no. 1 (Winter 1949): 45./object /P _1891 -0511 -93 -

James Roth, July 1941, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 32-167.

-

Roth, treatment report.

-

Forrest Bailey, February 2, 1984, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 32-167.

-

Nathan Sutton, August 12, 2010, treatment report, NAMA conservation file, 32-167.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

Jacques Augustin de Silvestre (1719–1809), Paris, by 1787–1811;

Silvestre’s posthumous sale, Catalogue Raisonné d’Objets d’Arts du Cabinet de Feu M. de Silvestre, ci-devant Chevalier de l’Ordre de Saint-Michel, et Maitre à Dessiner des Enfans [sic] de France, Hôtel de la Rochefoucault, Paris, February 28–March 23, 1811, no. 2, erroneously as Les Adieux d’un villageois et de sa femme au nourrisson que le père et la mère leur retirent [1];

Évrard Charlemagne Rhoné (Valenciennes, 1782–Paris, 1861), by May 7, 1861 [2];

Purchased from Rhoné’s posthumous sale, La Belle et Riche Collection de Tableaux Anciens et Modernes, des Écoles Flamande, Hollandaise et Française, Formant la Galerie de feu M. Évrard Rhoné, à Paris, 3 rue Drouot, Hôtel des Commissaires-Priseurs, Paris, May 7, 1861, no. 74, as Visite à la Nourrice, by Symphorien Casimir Joseph Boittelle (1813/1816–1897), May 7, 1861–April 25, 1866 [3];

Boittelle’s sale, Tableaux de l’École Française composant la Collection de M. Boittelle, Sénateur, Ancien Préfet de Police, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, April 24–25, 1866, no. 1, as La Première Leçon d’Amitié fraternelle;

Georges Wildenstein (1892–1963), Paris, by 1925;

Presumably sold by Wildenstein to his brother-in-law, Louis Isaac Paraf (b. 1871), Paris, by March 20, 1928–April 1929 [4];

Purchased from Paraf by D. A. Hoogendijk and Co., Amsterdam, stock number O. S. 855, as La première leçon d’amitié fraternelle, April 1929–December 27, 1932 [5];

Purchased from Hoogendijk by The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, as Family Scene, 1932.

Notes

[1] The dimensions given in the catalogue entry—“H. 29 p. 61., L. 37 p.”—are much closer to the Nelson-Atkins painting than to those of the same title by Etienne Aubry at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, and The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Further confirming this reference to NAMA’s painting is the inclusion in the lot description of an engraved reproduction of the painting by Nicolas Delaunay titled La première Leçon d’Amitié fraternelle, which was made after the Kansas City painting. See also Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, “Quelques Tableaux de Genre Inédits par Étienne Aubry (1745–1781),” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 2, no. 5 (1925): 82.

[2] [Alban Jules] Lambert, “Inventaire d’après décès de M. Rhoné,” April 26, 1861, Archives nationales, Paris, Minutier central des notaires de Paris, étude CXXII, cote 2094, folio 9, no. 155, as La Visite à la nourrice [photocopy in The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Collectors Files, Evrard Charlemagne Rhoné].

[3] This collector has been listed as Symphorien Casimir Joseph Boittelle and alternately as Edouard Charles Joseph Boittelle.

[4] Correspondence from Eliot Rowlands, Wildenstein and Co., New York, to Meghan Gray, NAMA, May 12, 2011 and June 28, 2011, NAMA curatorial files. Rowlands conjectures that Wildenstein may have bought the picture for Paraf.

[5] See D. A. Hoogendijk stock card, Rijksbureau voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie (RKD), Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague, Hoogendijk archives, as La première leçon d’amitié fraternelle. While the painting was in possession of Hoogendijk, he lent it to E. F. Heylel [?], Berlin, from May–June 1930.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

Etienne Aubry, Les adieux à la nourrice (Farewell to the Nurse), ca. 1776–77, oil on canvas, 20 7/16 x 24 3/4 in. (51.9 x 62.8 cm), Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA.

Etienne Aubry, Parting with a Wet-Nurse, 1777, oil on canvas, 20 1/2 x 24 13/16 in. (52 x 63 cm), The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow.

Reproductions

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

Nicolas Delaunay, after Etienne Aubry, Première leçon d’amitié fraternelle, 1787, engraving, 18 13/16 x 24 1/2 in. (47.8 x 62.2 cm), first proof image only, second proof image and colophon, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Preparatory Works

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

Etienne Aubry, L’Heureuse famille (The Happy Family), pencil heightened with white on paper, 16 5/16 x 8 11/16 in. (41.5 x 22 cm), private collection, location unknown, cited in Caroline Fossey, “Etienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781” (master’s thesis, Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989), no. 103, p. 474.

Etienne Aubry, La Visite à la nourrice (The Visit to the Nurse), ca. 1776, sepia wash on paper, 15 3/8 x 18 7/8 in. (39 x 48 cm), location unknown, illustrated in Caroline Fossey, “Etienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781” (master’s thesis, Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989), no. 104, pp. 474–76.

Known Copies

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

Attributed to Etienne Aubry, The Visit (also called La Visite à la Nourrice and La Première Leçon d’Amitié Fraternelle), copy in reverse, oil on canvas, 19 x 24 1/2 in. (48 x 62 cm), location unknown, illustrated in Objets d’Art Anciens des XVIe, XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles provenant pour la plupart de l’ancienne Collection du Baron Carl Mayer de Rothschild et appartenant à Madame de X . . . . (Paris: Galerie Charpentier, March 30, 1935), no. 82.

Attributed to Etienne Aubry, La visite à la nourrice (The Visit to the Nurse), copy in reverse, oil on canvas, 24 x 27 15/16 in. (61 x 71 cm), location unknown, illustrated in Importants Tableaux Anciens des XVIe, XVIIe, XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles notamment par: Constantin Guys, J.-B. Huet, Nicolas Loire, Demachy, J.-B. Peronneau, Peter Laer, Van Swanewelt, Van Falens, Roux, Michel Drolling, Théodore Géricault, Trorelli, Hubert Robert, Le Prince, Eugène Delacroix, Etc.; Objets d’Art des XVIIIe et XIXe Siècles; Très Bel Ameublement principalement du XVIIIe Siècle dont la plupart estampillés des grands Maitres-Ebénistes de leur temps tels que: Roussel, Avril, Delporte, Gourdin, Mauter, Criaerd, Lapic, Elleume, Fromageau, Dusautoy, Cordier, etc . . . ; Très Belle Tapisserie de Coypel (XVIIe Siècle), Tapis d’Orient (Versailles: Palais des Congrès, June 2, 1971), no. 62.

Attributed to Etienne Aubry, La visite à la nourrice (The Visit to the Nurse), oil on canvas, 19 11/16 x 25 9/16 in. (50 x 65 cm), location unknown, cited in Tableaux Anciens et Modernes; Portraits des Écoles Française, Flamande, Hollandaise, Italienne, etc.; Par ou Attribués à P. Alboni, E. Aubry, L. Boilly, P. Breughel, J.-B. Charpentier, Ch. Coypel, de Condamy, S. de Vos, G. Doré, M. Drolling, Giran-Max, Grimoud, D. Hals, J. Jordaens, Le Nain, Michel, M. Mierevelt, N. Molenaer, B. Monnoyer, A. Point, F. Pourbus, J. Ruisdael, P. P. Rubens, F. Snyders, A. van Dyck, J. Van Goyen, B. Van der Helst, M. Van Loo, J. Vernet, E. Vartz, etc., etc., (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, December 7, 1904), no. 2, unpaginated.

Attributed to Etienne Aubry, Visite à la nourrice (Visit to the Nurse), 18th century, copy in reverse, oil on canvas, Musée des beaux-arts et d’archéologie de Châlons-en-Champagne.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

Salon de 1777, Paris, opened August 25, 1777, no. 125, as Deux Époux, allant voir un de leurs enfans [sic] en nourrice, font embrasser le petit nourriçon par son frère aîné.

La Vie Parisienne au XVIIIe Siècle, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, March 20–April 30, 1928, no. 1, as La Visite à la Nourrice.

Tentoonstelling van Oude Kunst door de Vereeniging van Handelaren in Oude Kunst in Nederland, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, July–August 1929, no. 2, as La Première Leçon d’Amitié Fraternelle.

D. A. Hoogendijk en Co.: Oude Schilderijen, Oude Teekeningen, D. A. Hoogendijk en Co., Amsterdam, October 1929, no. 2, as La première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

Tentoonstelling van Oude Schilderijen, Rotterdamsche Kunstkring, Amsterdam, November 16–December 9, 1929; Pulchri Studio, The Hague, December 14, 1929–January 6, 1930, no. 2, as La première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

Exhibition of Figure Paintings, University of Iowa, Iowa City, November 5–30, 1936, no. 1, as The Visit.

Pictures of Everyday Life: Genre Painting in Europe, 1500–1900, Carnegie Institute, Department of Fine Arts, Pittsburgh, October 14–December 12, 1954, no. 67, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

The Century of Mozart, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, January 15–March 4, 1956, no. 1, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Homage to Mozart: A Loan Exhibition of European Painting, 1750–1800, Honoring the 200th Anniversary of Mozart’s Birth, Wadsworth Athenaeum, Hartford, CT, March 22–April 29, 1956, no. 1, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Great Stories in Art, The Denver Art Museum, February 13–March 27, 1966, no cat.

Genre, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, April 5–May 15, 1983, no. 19, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

The Rococo Age: French Masterpieces of the Eighteenth Century, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, October 5–December 31, 1983, no. 54, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Farewell to the Wet Nurse: Etienne Aubry and Images of Breast-Feeding in the Eighteenth-Century France, Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA, September 12, 1998–January 3, 1999, no. 3, as First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

George Washington: Military Leader, Statesman, and Legend, Oklahoma City Museum of Art, December 12, 2003–April 11, 2004, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Meghan L. Gray, “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

MLA:

Gray, Meghan L. “Etienne Aubry, The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship, 1773 or 1775,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2022. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.302.4033.

Explication des Peintures, Sculptures et Gravures, de Messieurs de l’Académie Royale, exh. cat. (Paris: Herissant, 1777), 25, as Deux Époux, allant voir un de leurs enfans [sic] en nourrice, font embrasser le petit nourriçon par son frère aîné [repr., in H. W. Janson, Catalogues of the Paris Salon 1673 to 1881, vol. 5, Paris Salons de 1775, 1777, 1779, 1781, 1783 (New York: Garland, 1977), unpaginated].

Pierre Samuel Du Pont de Nemours, “Lettre à la margrave Caroline-Louise de Bade,” [October 24, 1777], Les Trois Sallons de 1773, 1777 et 1779: Lettres à Son Altesse Sérénissime Madame la Margrave Régnante de Bade, Manuscript Accession 84, P. S. du Pont de Nemours Letters, p. 79, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, DE, as la visite à l’Enfant en nourrice.

Lettres Pittoresques, à l’Occasion des Tableaux Exposés au Sallon, en 1777 (Paris: P. F. Gueffier, [1777]), 22, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 190, as Les deux époux, allant voir un de leurs enfans [sic] en nourrice.

Les Tableaux du Louvre, Où Il n’y a Pas Le Sens Commun, Histoire Véritable (Paris: Cailleau, 1777), p. 17, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Collection Deloynes, vol. 10, no. 186, as deux Époux qui vont voir leur enfant en nourrice.

Pierre Jean Baptiste Nougaret [Jean Charles François Bidault de Montigny], Étrennes pittoresques, allégoriques et critiques; opuscule mélangé, Dont une partie peut faire suite et matière aux Annales de Nos Beaux-Arts (Paris: Veuve Duchesne et Cailleau, 1778), 116 [repr., in Paul Lacroix, “État de l’Académie Saint-Luc, au Moment de sa suppression, en 1776,” Revue Universelle des Arts 16 (October 1862–March 1863): 307].

[Carmontelle], Coup de Patte sur le Sallon de 1779, Dialogue; précédé et suivi de Réflexions sur la Peinture (Athens: Cailleau, 1779), 16.

Journal de Paris, no. 307 (November 3, 1787): 1323.

François Léandre Regnault-Delalande, Catalogue Raisonné d’Objets d’Arts du Cabinet de Feu M. de Silvestre, ci-devant Chevalier de l’Ordre de Saint-Michel, et Maitre à Dessiner des Enfans [sic] de France (Paris: [François Léandre Regnault-Delalande], 1810), 2, erroneously as Les Adieux d’un villageois et de sa femme au nourrisson que le père et la mère leur retirent.

[Alban Jules] Lambert, “Inventaire d’après décès de M. Rhoné,” April 26, 1861, Archives nationales, Paris, Minutier central des notaires de Paris, étude CXXII, cote 2094, folio 9, as La Visite à la nourrice [photocopy in The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, Collectors Files, Evrard Charlemagne Rhoné].

Catalogue de La Belle et Riche Collection de Tableaux Anciens et Modernes, des Écoles Flamande, Hollandaise et Française, Formant la Galerie de feu M. Évrard Rhoné, à Paris (Paris, 1861), 38, S3.

Pierre Defer, Catalogue Général des Ventes Publiques de Tableaux et Estampes Depuis 1737 jusqu’à nos Jours; Contenant: 1e Les Prix des plus beaux Tableaux, Dessins, Miniatures, Estampes, Ouvrages à figures et Livres sur les Arts; 2e des Notes Biographiques formant un Dictionnaire Des Peintres et des Graveurs les plus célèbres de toutes les Écoles, part 2, Tableaux, vol. 1, Dessins, Gouaches et Miniatures (Paris: Aubry, Clement, et Rapilly, 1865), 157.

Catalogue des Tableaux de l’École Française composant la Collection de M. Boittelle, Sénateur, Ancien Préfet de Police (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1866), IV–V, 1.

Pierre Defer, Catalogue Général des Ventes Publiques, de Tableaux et Estampes Depuis 1737 jusqu’à nos Jours; Contenant: 1e Les Prix des plus beaux Tableaux, Dessins, Miniatures, Estampes, Ouvrages à figures et Livres sur les Arts; 2e des Notes Biographiques formant un Dictionnaire Des Peintres et des Graveurs les plus célèbres de toutes les Écoles, part 2, Tableaux, vol. 2, Dessins, Gouaches et Miniatures (Paris: Aubry, Clement, et Rapilly, 1868), 562, as Première Leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

Julius Meyer and Wilhelm Schmidt, eds., Allgemeines Künstler-Lexikon (Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann, 1878), 378, as Première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

Edmond de Goncourt, La Maison d’un Artiste (Paris: G. Charpentier, 1881), 1:41, erroneously as Les Adieux à la Nourrice.

Émile Bellier de la Chavignerie and Louis Auvray, Dictionnaire Général des Artistes de l’École Française depuis l’origine des arts du dessin jusqu’à nos jours: Architectes, Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs et Lithographes (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1882), 1:25, as Jeunes époux visitant leur enfant chez sa nourrice [repr., in Émile Bellier de la Chavignerie and Louis Auvray, Dictionnaire Général des Artistes de l’École Française depuis l’origine des arts du dessin jusqu’à nos jours vol. 1 (New York: Garland, 1979), unpaginated].

Adolphe Siret, Dictionnaire historique et raisonné des peintres de toutes les écoles depuis l’origine de la peinture jusqu’à nos jours, 3rd ed. (Brussels: Chez les Principaux Libraires, 1883), 1:42, as première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

H. Hombron, Catalogue des Tableaux, Dessins et Gravures exposés dans les galeries du Musée de la Ville de Brest (Brest: L. Évian-Roger, 1891), 9.

Dr. Karl Obser, “Lettres sur les Salons de 1773, 1777 et 1779 adressées par Du Pont de Nemours à la margrave Caroline-Louise de Bade,” Archives de l’art français: recueil de documents inédits (Paris: Jean Schemit, 1908): 2:58–59, as Visite à l’enfant en nourrice.

Louis Hautecœur, “Le Sentimentalisme dans la Peinture Française de Greuze à David (Deuxième et Dernier Article),” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 1, no. 621 (March 1909): 276, as La Première leçon de l’amitié fraternelle.

Emile Dacier, “Livret du Salon de 1777 (Cabinet des Étampes de la Bibliothèque Nationale),” Catalogues de Ventes et Livrets de Salons illustrés par Gabriel de Saint-Aubin, vols. 3–4 (Paris: Société de Reproduction des Dessins de Maitres, 1910), 50, unpaginated.

H[ippolyte] Mireur, Dictionnaire des Ventes d’Art faites en France et à l’Étranger pendant les XVIIIme et XIXme siècles (Paris: Maison d’Éditions d’Œuvres Artistiques, 1911), 1:66, as Première leçon d’amitié fraternelle and Visite à la nourrice.

Florence Ingersoll-Smouse, “Quelques Tableaux de Genre Inédits par Étienne Aubry (1745–1781),” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 11, no. 754 (February 1925): 79–80, 82–83, (repro.), as Première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

Louis Réau, Histoire de la Peinture Française au XVIIIe siècle (Paris: G. van Oest, 1926), 2:57, as la Première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

La Vie Parisienne au XVIIIe Siècle, exh. cat. (Paris: Musée Carnavalet, 1928), 7.

François Boucher, “L’Exposition de la Vie Parisienne au XVIIIe Siècle au Musée Carnavalet,” Gazette des Beaux-Arts 17, no. 786 (April 1928): 206–07, 406, (repro.), as La Visite à la Nourrice.

François Boucher, “Une Exposition au Musée Carnavalet: La Vie Parisienne au XVIIIe Siècle,” Le Gaulois Artistique 2, no. 19 (April 7, 1928): 165, as Visite à la nourrice.

La Vie Parisienne au XVIIIe Siècle: Conférences du Musée Carnavalet (1928) (Paris: Payot, 1928), (repro.), as La Visite à la Nourrice.

Art News 27, no. 38 (July 13, 1929): 12, (repro.), as First Lesson of Brotherly Love.

Catalogus van de Tentoonstelling van Oude Kunst door de Vereeniging van Handelaren in Oude Kunst in Nederland, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: H. J. Koersen, 1929), 1, (repro.).

C. H. de Jonge, “De Nederlandsche Schilderijen op de Tentoonstelling van Oude Kunst te Amsterdam,” Oude Kunst 7, no. 2 (October 1929): 53.

D. A. Hoogendijk en Co.: Oude Schilderijen, Oude Teekeningen, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: D. A. Hoogendijk, 1929), 5, (repro.).

Tentoonstelling van Oude Schilderijen, Rotterdamsche Kunstkring, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: D. A. Hoogendijk, 1929), 5, (repro.).

advertisement, Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 55, no. 321 (December 1929): lx, (repro.), as La Première Leçon d’Amitié Fraternelle.

Tentoonstelling van Oude Schilderijen,“Pulchri Studio,” ’s-Gravenhage, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: D. A. Hoogendijk, 1929), 5, (repro.).

Oude Schilderijen: Catalogus van eenige schilderijen en een beeldhouwwerk door de firma D. A. Hoogendijk en Co. te Amsterdam afgestaan voor de tentoonstelling, die de “Vereeniging van Handelaren in Oude Kunst in Nederland” gedurende de maanden juli en augustus 1929, in het Rijksmuseum te Amsterdam zal Houden (Amsterdam: D. A. Hoogendijk, [1929]), unpaginated, (repro.), as La Première Leçon d’Amitié Fraternelle.

Karl T. Parker, “Etienne Aubry (1745–1781): Study of a Standing Male Figure,” Old Master Drawings 5, [no. 18] (September 1930): 38, as La Première Leçon d’Amitié fraternelle.

Erna Schiefenbusch, “L’Influence de Jean-Jacques Rousseau sur les Beaux-Arts en France,” trans. Elie Moroy, Annales de la Société Jean-Jacques Rousseau 19 (1930): 139, as Visites à la nourrice and Première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

M[inna] K. P[owell], “The Nelson Art Gallery a Lure, Although Incomplete: Exterior Finishing Touches and Landscaping Bring Many Visitors—The Opening Date Still an Uncertainty,” Kansas City Star 53, no. 107 (January 2, 1933): 8, as Interior Scene.

Kansas City Star 53, no. 113 (January 8, 1933): 4, (repro.), as A French Cottage Interior.

“Nelson Gallery of Art Special Number,” Art Digest 8, no. 5 (December 1, 1933): 21, 25, (repro.), as Interior Scene.

“Complete Catalogue of Paintings and Drawings,” in “The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 28, as Interior Scene.

Alfred M. Frankfurter, “The Paintings in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art,” in “The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art, Kansas City Special Number,” Art News 32, no. 10 (December 9, 1933): 30.

Luigi Vaiani, “Art Dream Becomes Reality with Official Gallery Opening at Hand: Critic Views Wide Collection of Beauty as Public Prepares to Pay its First Visit to Museum,” Kansas City Journal Post 80, no. 187 (December 11, 1933): 7.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Handbook of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1933), 46, (repro.), as Interior Scene.

A. J. Philpott, “Kansas City Now in Art Center Class: Nelson Gallery, Just Opened, Contains Remarkable Collection of Paintings, Both Foreign and American,” Boston Sunday Globe 125, no. 14 (January 14, 1934): 16, as Interior Scene.

“A Thrill to Art Expert: M. Jamot is Generous in his Praise of Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Times 97, no. 247 (October 15, 1934): 7.

Exhibition of Figure Paintings, exh. cat. ([Iowa City]: University of Iowa, 1936), unpaginated.

The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, The William Rockhill Nelson Collection, 2nd ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1941), 167, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Louis Hautecœur, Les Peintres de la Vie Familiale: Évolution d’un Thème (Paris: Éditions de la Galerie Charpentier, 1945), 80, as La première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

Michel Florisoone, Le Dix-Huitième Siècle (Paris: Pierre Tisné, 1948), 71, (repro.), as La Première Leçon d’Amitié Fraternelle.

Paul L. Grigaut, “Marmontel’s ‘Shepherdess of the Alps’ in Eighteenth Century Art,” Art Quarterly (The Detroit Institute of Arts) 12, no. 1 (Winter 1949): 40–41, 44, 46, 47n19, (repro.), as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Pictures of Everyday Life: Genre Painting in Europe, 1500–1900, exh. cat. (Pittsburgh: Carnegie Institute, Department of Fine Arts, 1954), (repro.).

Patrick J. Kelleher, “The Century of Mozart: January 15 through March 4, 1956,” exh. cat., Bulletin (The Nelson Gallery and Atkins Museum) 1, no. 1 (January 1956): 13, 25, 58, (repro.).

Mario Praz, The Hero in Eclipse in Victorian Fiction, trans. Angus Davidson (London: Geoffrey Cumberlege and Oxford University Press, 1956), 26.

Evan H. Turner, Homage to Mozart: A Loan Exhibition of European Painting, 1750–1800, Honoring the 200th Anniversary of Mozart’s Birth, exh. cat. (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum, 1956), 7, 15, (repro.).

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 114, (repro.), as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Germain Bazin, et al., Kindlers Malerei Lexikon (Zurich: Kindler, 1964), 1:148, as Die erste brüderliche Lektion.

Jacques Thuillier and Albert Châtelet, French Painting: From Le Nain to Fragonard, trans. James Emmons (Geneva: Skira, 1964), 229, as The First Lesson of Brotherly Friendship.

Ralph T. Coe, “The Baroque and Rococo in France and Italy,” Apollo 96, no. 130 (December 1972): 539, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship [repr., in Denys Sutton, ed., William Rockhill Nelson Gallery, Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City (London: Apollo Magazine, 1972), 71, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship].

Anita Brookner, Greuze: The Rise and Fall of an Eighteenth-Century Phenomenon (Greenwich, CT: New York Graphic Society, 1972), 142, (repro.), as La Première Leçon d’Amitié Fraternelle.

Ross E. Taggart and George L. McKenna, eds., Handbook of the Collections in The William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, Kansas City, Missouri, vol. 1, Art of the Occident, 5th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1973), 133, 136, (repro.), as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Phyllis Hattis, Four Centuries of French Drawings in The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1977), 215, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Elizabeth LaMotte Cates Milroy, “Keeping Abreast of Etienne Aubry” (master’s thesis, Williams College, 1979), 6, 12, 20, viii, (repro.).

Tom L. Freudenheim, ed., American Museum Guides: Fine Arts (New York: Macmillan, 1983), 112, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Ross E. Taggart and Laurence Sickman, Genre, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1983), 13.

Eric M. Zafran, The Rococo Age: French Masterpieces of the Eighteenth Century, exh. cat. (Atlanta: High Museum of Art, 1983), 107, 118–19, (repro.).

Cissie Fairchilds, Domestic Enemies: Servants and Their Masters in Old Regime France (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 215, as The First Lesson in Brotherly Feeling.

David Wakefield, French Eighteenth-Century Painting (New York: Alpine Fine Arts Collection, 1984), 136, as First Lesson in Brotherly Love.

Jacques Foucart, ed., Musée du Louvre: Nouvelles acquisitions du Département des Peintures (1983–1986) (Paris: Editions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1987), 124, (repro.), as La Visite à la nourrice.

Important Old Master Drawings: The Properties of The Bernasconi Family and from various sources (London: Christie, Manson and Woods, December 8, 1987), 97, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Pierre Rosenberg and Marion C. Stewart, French Paintings, 1500–1825: The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (San Francisco: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, 1987), 105, as First Lesson in Fraternal Friendship.

Caroline Fossey, “Etienne Aubry: Peintre du Roi, 1745–1781” (master’s thesis, Université de Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne, 1989), no. 105, pp. 25–26, 474–83, as La Visite à la Nourrice or Première Leçon d’Amitié Fraternelle.

Ursula Hilberath, “Ce sexe est sûr du nous trouver sensible”: Studien zu Weiblichkeitsentwürfen in der französischen Malerei der Aufklärungszeit (1733–1789) (Alfter, Germany: VDG, Verlag und Datenbank für Geisteswissenschaften, 1993), 112, 114, 338, 398, (repro.), as Deux Époux, allant voir un de leurs enfans [sic] en nourrice, font embrasser le petit nourricon par son frère aîné.

Patricia R. Ivinski et al., Farewell to the Wet Nurse: Etienne Aubry and Images of Breast-Feeding in Eighteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 1998), 8–9, 12, 14, 17n4, 21, 41, (repro.).

MMI, exh. cat. (London: Hall and Knight, 2001), 156, as La Première Leçon d’Amitié Fraternelle.

Colin B. Bailey, Philip Conisbee, and Thomas W. Gaehtgens, The Age of Watteau, Chardin, and Fragonard: Masterpieces of French Genre Painting, exh. cat. (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press in association with the National Gallery of Canada, 2003), 397, 399, as Deux Époux, allant voir un de leurs enfants en nourrice, font embrasser le petit nourrisson par son frère ainé.

Gabriela Jasin, “‘De Nos Ambitieux, Vous Êtes Le Symbole’: Aspects of Childhood in Eighteenth-Century French Art” (master’s thesis, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, 2003), 96n200, as La première leçon d’amitie [sic] fraternelle.

Pierre Sanchez, Dictionnaire des Artistes Exposant dans les Salons des XVII et XVIIIeme Siècles à Paris et en Provence, 1673–1800 (Dijon: L’Échelle de Jacob, 2004), 1:97, as Deux Époux, allant voir un de leurs enfans [sic] en nourrice, font embrasser le petit nourriçon par son frère aîné.

Emma Barker, Greuze and the Painting of Sentiment (Cambridge, U. K.: University of Cambridge, 2005), 191–92, 194, (repro.), as La Prémière [sic] leçon de l’amitié fraternelle.

Emmanuel-Charles Bénézit, Dictionary of Artists (Paris: Gründ, 2006), 1:820, as The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship and Visiting the Wet Nurse.

Philip Conisbee, ed., French Genre Painting in the Eighteenth Century (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2007), 239n35.

J. F. Heijbroek and A. Th. P. van Griensven, Kunst, kennis en kwaliteit: De Vereeniging van Handelaren in Oude Kunst in Nederland 1911-heden (Zwolle: Waanders, 2007), 44, (repro.).

Karen Yeager Kimball, “Milk Machines: Exploring the Breastfeeding Apparatus” (master’s thesis, University of North Texas, 2008), 32, as First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship.

Ryan Lee Whyte, “Painting as Social Conversation: The petit sujet in the Ancien Régime” (PhD diss., University of Toronto (Canada), 2008), 185, 320, (repro.).

Marie‐France Morel, “Images de nourrices dans la France des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles,” Paedagogica Historica: International Journal of the History of Education 46, no. 6 (December 2010): 805, as Première leçon d’amitié fraternelle.

Gal Ventura, Maternal Breast-Feeding and Its Substitutes in Nineteenth-Century French Art (Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 2018), (repro.).