The Collecting of French Paintings in Kansas City

- Aimee Marcereau DeGalan

For the great doesn’t happen through impulse alone, [it] is a succession of little things that are brought together.

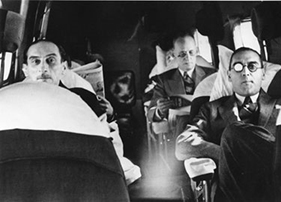

On a cold day in early December 1933, a handful of the world’s leading French art dealers, among them Paul Rosenberg (1861–1959), Pierre Durand-Ruel (1899–1961), and Pierre Matisse (1900–1989), boarded a small plane en route to Kansas City, Missouri, to attend the opening of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, originally known as the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts (Fig. 1). As Pierre Matisse noted much later to Paul Rosenberg’s son, Alexandre, “We had begun to emerge from the mess of the Great Depression and this opening seemed quite an event.“2Pierre Matisse to Alexandre Rosenberg, December 1, 1969 (PR II.22.M), The Paul Rosenberg Archives, Gift of Elaine and Alexandre Rosenberg, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York. Indeed, despite the economic devastation around the country, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art opened its doors to much fanfare. Founded more than fifty years after most other major American art institutions—including the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1870), the Philadelphia Museum of Art (1876), the Art Institute of Chicago (1879), the St. Louis Art Museum (1879), and the Detroit Institute of Arts (1883)—and with virtually no existing collection from its founders, the Nelson-Atkins got off to a late start. Yet through a miraculous combination of people, circumstance, and resources harnessed by the vision of its founders, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art amassed a collection that ranks among the best in the country, buoyed by a number of distinguished and bold acquisitions within its holdings of French paintings. It took time, however, to assemble such a great collection—and it almost did not happen at all.

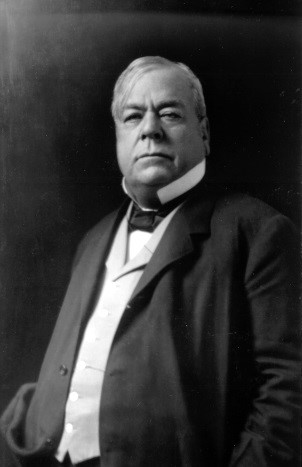

Fig. 2. Portrait of William Rockhill Nelson, date unknown, photograph, NAMA Archives

Fig. 2. Portrait of William Rockhill Nelson, date unknown, photograph, NAMA Archives

Fig. 3. Portrait of Mary McAfee Atkins, date unknown, photograph, NAMA Archives

Fig. 3. Portrait of Mary McAfee Atkins, date unknown, photograph, NAMA Archives

Long before the museum opened its doors in 1933, it began in earnest to form a collection and to design and erect a building with funds combined from two major donors: newspaper publisher William Rockhill Nelson (1841–1915; Fig. 2) and retired schoolteacher Mary McAfee Atkins (1836–1911; Fig. 3), both of whom traveled to Europe many times, cultivating a taste for art. Funds from the 1923 bequest of Nelson family attorney Frank F. Rozzelle and from Nelson’s daughter, Laura Nelson Kirkwood, who died in 1926, and her husband, Irwin Kirkwood, who died a year later in 1927, supplemented the original funds, amounting to a total of over $11 million. Trustees broke ground for the new building on July 16, 1930; however, at this point there were almost no artworks to go inside.

Nelson-Atkins museum co-founder William Rockhill Nelson had definitive ideas about

building an art collection. He felt that most people in Kansas City and its

surrounding areas would never have the opportunity to see great art from around the

world, or even in major public collections in New York, Washington, or Chicago, nor

did he foresee the opportunity to bring such masterworks to Kansas City. As such,

in the late 1890s he considered two paths for the development of a collection:

acquire second-rate works or have copies made of great works of art that had

already been proven to be masterpieces. Nelson supported the latter scenario, as

he believed that this would serve the greatest good for the greatest number of

people.3Nelson opened the Western Gallery of Art in 1897 with nineteen replica oil paintings of noted artworks, made in the exact scale as the originals (including the frames); more than thirty plaster casts of significant sculptures; and 450 photographs of paintings representing the most important schools of the past. William Rockhill Nelson: The Story of a Man, a Newspaper and a City (Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1915), 178–79. See also Nicholas S. Pickard, "The Friends of Art of the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum: A History," typescript, 1981, p. A6, cited in Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 9, 15n9. Upon Nelson’s death in 1915, his will laid

out further stipulations that would shape the future course of the museum. In an

effort to promote the acquisition of artists whose merits had been proven to

withstand the test of time, Nelson stipulated in his will that the income of his

trust should not be used to purchase artworks or the reproduction of artworks by

any artist who had not been dead for at least thirty years.4Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 11.

This proviso meant that when the trustees appointed to enact Nelson’s will—Arthur

Hyde, Herbert V. Jones, and J. C. Nichols5William Rockhill Nelson’s will stipulated that his trustees be appointed by three university presidents from Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma (Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 11). —started

to direct resources toward building the collection following Laura Nelson

Kirkwood’s death in 1926, they were not allowed to consider works by many, if not

most, of the early modernist French artists, including Paul Cezanne (1839–1906),

Paul Gauguin (1848–1903), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), or Claude Monet

(1840–1926), among others. This also presented a barrier to purchasing works by

major living artists like Pablo Picasso (Spanish, active in France, 1881–1973) and

Henri Matisse (1869–1954). Interestingly, though, the museum was not prohibited

from receiving works by living or recently deceased artists as gifts or bequests.

For example, in 1936, Baltimore collector Saidie A. May gave the museum The Little

Tragedy by André Masson (1896–1987), which the artist had painted only three

years earlier, in 1933 (Fig. 4; 36-20/2). The stipulation in Nelson’s will was

still limiting, however, and it accounts for some of the notable absences in the

museum’s collection today, as market shifts have made acquiring paintings by some

of these artists, like Picasso, nearly impossible.

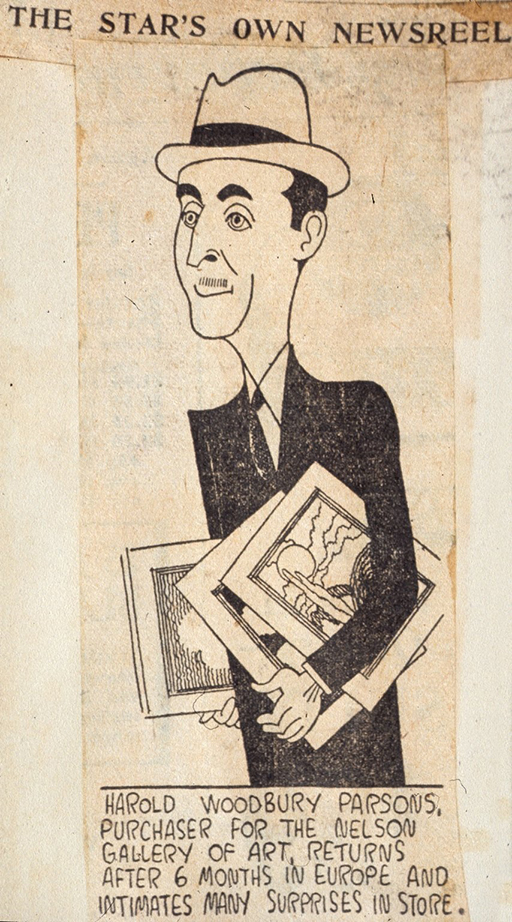

So how did the museum’s Board of Trustees approach collecting? To start, they

overturned Nelson’s preference for copies; they appointed the director of the

Kansas City Art Institute, R. A. Holland (1868–1959; Fig. 5) first as art advisor,

in 1927, and then as curator of collections, in 1930; and they brought in

Massachusetts native Harold Woodbury Parsons (1882–1967; Fig. 6) as an art advisor

in 1930.6Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (Kansas City, MO: University of Missouri Press and Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2020), 84–86. R[obert]. A[llen]. Holland was acting director of the City Art Museum of Saint Louis from 1911 to 1912 and director from 1912 to May 31, 1922. He became director of the Kansas City Art Institute in September 1924. He retired from the Kansas City Art Institute in March 1933 and had moved back to Saint Louis by October 1933. He probably relinquished his position as art advisor to NAMA around the same time. Thanks to Jenna Stout, Museum Archivist, Saint Louis Art Museum; and Elizabeth Davis, Visual and Archival Resources Specialist, Kansas City Art Institute, for their help in expanding Holland’s biography. Parsons first came to the Trustees’ attention in 1927 via a letter from Frederick A. Whiting, then director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, whom they had consulted about the new Nelson-Atkins building. See Frederic Allen Whiting to J. C. Nichols, March 8, 1927, NAMA Archives. Parsons also served as the art advisor to

the Cleveland Museum of Art from 1925 to 1941. He worked in a similar capacity for

private collector Robert Lehman as well as other museums, including the Museum of

Fine Arts in Boston, the Cloisters in New York, and, later, for the Joslyn Art

Museum in Omaha and the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa.7See Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 24.

Parsons began his role for the Nelson in April 1930, one month after Holland

began.8Holland received $1,200 annually, whereas Parsons received $5,000 per year inclusive of travel expenses. For this fee, Parsons closely watched the New York art market from December to May and made recommendations for acquisitions. From June to November, he traveled in Europe aboard his yacht Saharet, which was based in Genoa, and he kept current on the European market. See Harold Woodbury Parsons to J. C. Nichols, August 5, 1932, as cited in Eliot Rowlands, Italian Paintings 1300–1800 (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), 16, 22n7.

Parsons wasted no time in making recommendations for the Nelson-Atkins. His collecting philosophy prioritized aesthetics over historical value. As such, he suggested many bold choices that did not always accord with museum Trustees' sensibilities, many of whom preferred Barbizon-era painters like Théodore Rousseau (1812–1867) and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), examples by whom Trustees had already secured prior to appointing Parsons. The Rousseau painting The Eagle’s Nest, Forest of Fontainebleau (1837–67; 30-11) was the first French painting to enter the museum’s collection. The Trustees had acquired it in 1930 through Findlay Galleries in Kansas City, founded by William Wadsworth Findlay in 1870. The Findlay family subsequently expanded operations, with later generations opening their own distinct galleries in other cities, including New York. The Nelson-Atkins acquired twelve works from the Findlay family, two of which were later deaccessioned.9Corot, The Grove of Willows (D31-48), and Émile van Marcke (French, 1827–1890), Noonday Rest (D32-104). Of the remaining pictures, six, including the Rousseau, were French.10The other paintings include Constant Troyon (1810–1865), Cattle Pasture in the Touraine (1853; 31-47); Charles Émile Jacque (1813–1894), Sheep at the Watering Hole, (painted around 1888; 31-88); Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) Jo, The Irish Woman (ca. 1866–1868; 32-20); a Toulouse-Lautrec lithograph, The Milliner, Renée Vert (1893; F86-33); and, from Wally’s son Peter Findlay at his gallery in in New York, Edgar Degas’s Dancer Making Points (1879–1880; 2008.53).

The 1930s were a flurry of collecting activity at the Nelson-Atkins. The Trustees wanted to make a creditable showing for the opening of the museum in 1933, and they wanted to take advantage of the Depression’s downturned market. The museum acquired forty-two French pictures, among other objects, during these years—the greatest number of French paintings acquisitions of any decade in museum history. Among them, the monumental canvas Waiting, painted between 1853 and 1861 by Jean-François Millet (1814–1875; 30-18), was the second major French painting to enter the collection. When Parsons spotted the painting at Knoedler and Company in New York, he wrote to museum Trustees: “There came forth an unexpected marvel; one of Millet’s most famous and moving masterpieces; a superb great canvas which alone would put our museum on the map.”11Cited in "Three Great Paintings: The Nelson Gallery Gets Added Variety in Collection," Kansas City Star, June 20, 1930. Indeed, it remains an anchor in the collection, and its genesis was very personal for Millet, providing an opportunity for visitors to learn about mid-nineteenth-century French art through the painting’s affecting backstory.

Parsons immediately turned around and presented another masterpiece, Nicolas Poussin’s (1594–1665) Triumph of Bacchus (31-94), painted in 1635–1636 for Armand Jean du Plessis, Cardinal Richelieu (1585–1642), which originally formed one of a group of paintings Richelieu commissioned from the artist for his château in Poitou. The painting had been with descendants of George William Frederick Howard, 7th Earl of Carlisle (1802–1864); recognizing its quality, Parsons sent J. C. Nichols a telegram on June 2, 1931, imploring him to “URGE AUTHORITY [to] OFFER LORD CARLISLE SEVEN THOUSAND POUNDS [for the] INCOMPARABLE GREAT POUSSIN STOP CONVINCED PRESENT IS MOMENT [to] PURCHASED [sic] GREAT MASTERPIECES STOP.”12Harold Parsons to J. C. Nichols, June 2, 1931, NAMA Archives. The Poussin is arguably the largest and most ambitious example from the seventeenth century to enter the collection.

In 1931, the museum acquired its second example from the seventeenth century, an

idyllic classical landscape by Claude Lorrain (1604/1605–1682) entitled Landscape with a Piping Shepherd (1667; 31-57).

Acquired from Durlacher Brothers in New York and exhibited at the Nelson-Atkins

upon its opening in 1933, the painting caught the eye of a French curator from the

Louvre a year later, who pronounced it the finest Claude in existence.13M[inna]. K. P[owell]., "In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art," Kansas City Star, January 28, 1938.

The museum also acquired several important eighteenth-century French paintings

during this decade, including, in 1931, two pictures by Jean-Baptiste Greuze

(1725–1805), Head of a Girl (completed 1770 or later; 31-55)

and The Nursemaids (painted around 1765; 31-61);

and, in 1932, François Boucher’s (1703–1770) Jupiter in the Guise of Diana, and the Nymph Callisto (1759; 32-29)

and Etienne Aubry’s (1745–1781) The First Lesson of Fraternal Friendship (1773 or 1775; 32-167).

While these acquisitions were important to the development of the collection, they

were in keeping with prevailing tastes of the period. More daring acquisitions were

forthcoming. In April 1931, a letter from Valentine Dudensing, of Valentine Gallery

in New York, to Harold Parsons signaled the direction.14Letter from Dudensing Valentine, Valentine Gallery, New York City, to Parsons, April 1, 1931, NAMA curatorial files.

Dudensing noted that he recalled Parsons’s interest in Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890)

and that he might have a painting of a peasant man with a large straw hat coming to

New York to show a collector. Parsons passed on the opportunity, indicating it was

too expensive. At the very same moment, Parsons had another painting by Van Gogh

sent to the museum on approval.15Van Gogh was not yet a household name in 1931; however, a catalogue raisonné published in 1928 may have fueled early interest by Kansas City collectors. J.-B. de la Faille, L’Œuvre de Vincent Van Gogh: Catalogue Raisonné (Paris: Éditions G. Van Oest, 1928). It was

Van Gogh’s Olive Trees,

a haunting work that the tormented young artist painted in the summer and fall of

1889 while he was recuperating in a mental health facility in Saint-Rémy. There

were a handful of dealers managing the growing attention of Van Gogh’s work in

Europe; however, interest in his work in America was still in its nascent stages.16Van Gogh’s works were featured in the Armory Show in 1913 and in a solo exhibition at the Montross Gallery in New York. Olive Trees was featured in the latter exhibition. Walter Feilchenfeldt felt that neither of these exhibitions made any great impact on the future collecting of Van Gogh in America. See Walter Feilchenfeldt, Van Gogh in France (London: Philip Wilson, 2013), 28–29.

As a result, museum Trustees were initially reticent to acquire a work by this

modern master and needed more convincing.

Enter Effie Seachrest (1869–1952; Fig. 7), a retired art teacher and local dealer

who championed modernist art. She often brought pictures on consignment from New

York and Paris dealers to her Kansas City gallery.17It is uncertain whether Miss Seachrest received a commission for items purchased on consignment. She helped Parsons select paintings at Durand-Ruel. For more information on Effie Seachrest, see The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Homage to Effie Seachrest, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, 1966).

She and Parsons worked together to secure the Van Gogh for the museum in Kansas

City. In a letter to J. C. Nichols dated March 10, 1931, Parsons recounted his

discovery of the painting and signaled Miss Seachrest’s role in securing the

painting’s support:

I have found here at Durand-Ruel’s a masterpiece by Vincent van Gogh. . . . It is a picture which will perhaps not appeal immediately to my Trustees, but in this case I am going to ask you to let me guide you to those qualified to judge in this field which, I feel, the Trustees will come to understand only after further experience. . . . Miss Seachrest was as much overwhelmed by the picture as I had been and will lend her influence in Kansas City towards consummating the purchase. I suspect that it can be secured without Museum funds. May I have your permission to have this picture sent on approval to the Art Institute to be hung, together with our Sisley and Ribot, and then supported by other pictures which I have been selecting, together with Miss Seachrest, here in New York?18Harold Woodbury Parsons to J. C. Nichols, March 10, 1931, NAMA archives. The paintings by Alfred Sisley, Landscape (D31-78), and by Theodule Augustin Ribot (1823–1891), The Story (D31-70), had both been recently acquired and were later deaccessioned.

Since the museum was not yet built, the Van Gogh was sent on approval and placed on view at the Kansas City Art Institute beginning on March 18, 1931. Seachrest’s influence took the form of a petition she spearheaded that was signed by approximately 135 people who encouraged the museum to purchase the work, an effort that finally bore fruit in January 1932.19See "Petition to purchase Van Gogh Olive Orchards," ca. April 21, 1931, NAMA Archives; and J. C. Nichols to Sybil Brelsford, July 21, 1931, NAMA Archives. See also " Pictures remaining in the Art Institute after May 20, 1932," May 20, 1932, NAMA Archives. This acquisition marks the second known painting by Van Gogh to enter an American public collection, and the first modernist French painting to be acquired for the Nelson-Atkins museum.20The Detroit Institute of Arts acquired Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat in 1922 (City of Detroit Purchase, 22.13), making it the first public art institution in America to acquire a work by Van Gogh. For a Midwest institution to make such a bold acquisition that early in its tenure, before it had even opened its doors to the public, was remarkable.

Seachrest continued to play a major role in garnering local interest in French art generally, and Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters specifically, through her Little Gallery in the Woods, where she hosted local society women for art classes and encouraged them to acquire modernist French art. One successful effort included the rare Impressionist snow scene by Alfred Sisley (English, born France, 1839–1899), Embankment at Billancourt—Snow (ca. 1879; 75-6), which Miss Seachrest purchased from Durand-Ruel in 1927 and probably sold to the Brace family of Kansas City. They in turn gave the painting to the Nelson-Atkins in 1975. Other important acquisitions of French pictures by the museum in the 1930s include Georges Seurat’s (1859–1891) Study for Bathers at Asnières (1883; 33-15/3) and Camille Pissarro’s (1830–1903) The Market at Gisors (1895; 33-150) in 1933. In 1935, the museum received the gift of a pastel by Edgar Degas (1834–1917): After the Bath, Seated Woman Drying Herself (ca. 1885; 35-39/1) from Mrs. David M. Lighton of Kansas City.

How the pastel found its way into the museum is a fascinating, meandering tale. William Rockhill Nelson originally acquired the pastel when he was in Paris in 1896, while Degas was still living, and brought it home to Kansas City. Clearly, his own habit of collecting what would have been at the time very modern art did not reflect the acquisition policies he sought to enforce at the museum. The pastel passed to his daughter, Laura Nelson Kirkwood, and upon her death in 1926 it became part of her residuary trust. By December 28, 1927, R. A. Holland selected the pastel to go to the Nelson-Atkins museum collection; however, for reasons that remain unclear (quite possibly, it was simply overlooked), it became part of the sale of the contents of Oak Hall, Nelson’s former residence. The timing of the sale roughly coincided with the formation of Loew’s Midland Theater in Kansas City, when its trustees, among them Kansas City native Herbert M. Woolf (1880–1964), were looking to furnish their new theaters. Loew’s purchased the entire contents of Oak Hall with that goal in mind. Recognizing that the pastel was an anomaly among the items acquired in the sale, Woolf gave it to his sister, Mrs. David M. Lighton, née Gertrude Woolf (ca. 1877–1961; Fig. 8).21See manuscript note from a conversation with Lighton’s son, Alfred, May 1, 1989, NAMA curatorial file. Mrs. Lighton was an artist, founder of the Lighton Studio for the Kansas City Society of Artists, and a Trustee of the Kansas City Art Institute. She also became the second vice president of the museum’s budding Friends of Art group, which became instrumental for the acquisition of modern art. In 1935, then-director Paul Gardner persuaded Mrs. Lighton to give the pastel to the museum.22See "Mrs. Lighton’s enthusiasm and leadership," The Independent, July 23, 1973. The article is transcribed in a post of the same title dated January 30, 2011, at 1718 Holly Street, a blog dedicated to Lighton’s legacy: http://kansas-city-society-of-artists.blogspot.com/2011/01/mrs-lightons-enthusiasm-and-leadership.html. I am grateful to Meghan Gray for pointing me to this source.

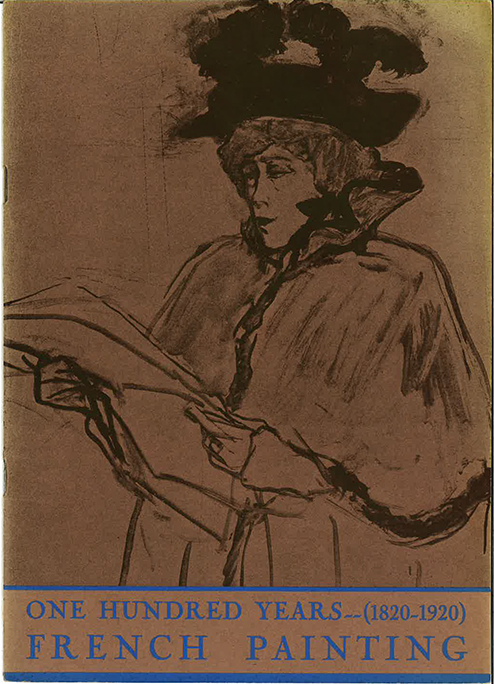

Fig. 9. Cover of One Hundred Years of French Painting, 1820–1920, featuring Jane Avril Looking at a Proof by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

Fig. 9. Cover of One Hundred Years of French Painting, 1820–1920, featuring Jane Avril Looking at a Proof by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

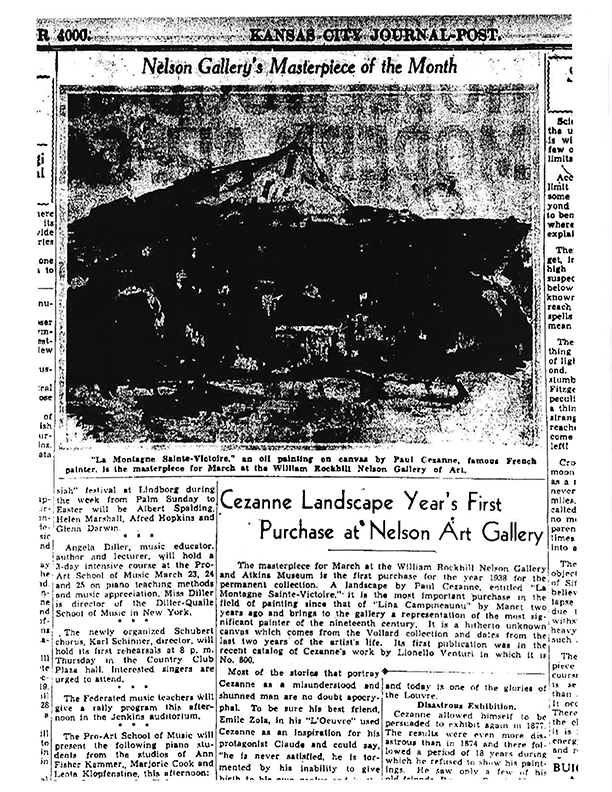

Fig. 10. Paul Cezanne’s Mont Saint-Victoire, ca. 1902–06, reproduced in “Cezanne [sic] Landscape Year’s First Purchase at Nelson Art Gallery,” Kansas City Journal-Post, March 6, 1938, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire

Fig. 10. Paul Cezanne’s Mont Saint-Victoire, ca. 1902–06, reproduced in “Cezanne [sic] Landscape Year’s First Purchase at Nelson Art Gallery,” Kansas City Journal-Post, March 6, 1938, as La Montagne Sainte-Victoire

The second half of the decade

saw a continuation of interest in and acquisition of important French pictures.

From March 31 to April 28, 1935, the museum mounted an exhibition entitled One

Hundred Years of French Painting, 1820–1920. The cover of the catalogue featured

a painting entitled Jane

Avril Looking at a Proof by Toulouse-Lautrec (Fig. 9), lent by Wildenstein and

Co. in New York. Eighty years later, this painting found its way back to the museum

as a gift of Henry and Marion Bloch (2015.13.27).23In an oft-recounted story from Henry Bloch, when museum director Marc Wilson was negotiating the Bloch gift of paintings, Bloch wanted to retain the Toulouse-Lautrec in his collection. Wilson asked Bloch to concede if he could prove that the drawing had been at the Nelson-Atkins in its early history. Bloch felt certain he knew the exhibition history at the Nelson-Atkins, and he took the bet. He lost, and today the drawing is in the museum’s collection. In

1936, an enigmatic portrait of a young girl, Lise Campineau by Edouard Manet (1832–1883),

entered the collection (1878; 36-5), followed a year later by a second Van Gogh

painting, this one an early portrait, Study of a Peasant’s Head (37-1)

painted in 1885 during the artist’s period in Nuenen. 1938 saw the addition of two

singularly important Post-Impressionist pictures, Cezanne’s Mont Saint-Victoire (Fig. 10; 38-6),

and Gauguin’s melancholic portrait Faaturuma (38-5),

painted during the artist’s first visit to Tahiti in 1891. Trustees purchased both

paintings from Wildenstein, after considerable negotiations, for a combined price

of $55,000.24See Trustees’ minutes, January 3, 1938, in which the following was recorded: "Landscape by Cézanne and Revery by Gauguin, offered by Wildenstein. Mr. Nichols reported that after considerable negotiations, he had been able to reduce the price on the two objects to $55,000. The purchase was approved. Paid January 3rd, 1938, Voucher #472. Original price was $65,000.00." The Cezanne marked the museum’s first

example by this artist in the collection. Critics hailed the acquisition and

considered it the “most important purchase in the field of painting since that of

‘Lina Capineaunu’ [sic] by Manet two years ago.“25"Cezanne Landscape Year’s First Purchase at Nelson Art Gallery," Kansas City Journal-Post, March 6, 1938.

The painting, which was previously unknown, came from the inventory of Cezanne’s

art dealer, Ambroise Vollard, and it dates from the last two years of the artist’s

life. It is one of many paintings the artist made of this iconic mountain that

looms over the countryside surrounding Aix-en-Provence, and it represents not only

his attachment to his native landscape but also his practice of returning to the

same motif repeatedly.

The 1940s saw a major shift

in the museum and in the country as the United States entered the Second World War.

Many Americans were called to service, including then-director Paul Gardner. He

recommended his secretary, Ethlyne Jackson (Fig. 11), for the role of acting

director, which the Trustees readily accepted. Jackson had an undergraduate degree

in art history and a year of graduate school from Yale.26Information about Ethlyne Jackson and her role at the museum is taken largely from Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 61.

She had served as the director’s secretary since August 1933; however, during her

tenure she assumed many additional roles, including curatorial oversight of the

American period rooms and decorative arts. Jackson assumed her position as interim

director in November 1942 and remained in the role until the end of 1945. During

this period, the museum did not acquire any French paintings, as the European art

market was effectively closed to American purchasers while much of Europe was

occupied by Hitler’s armies. However, in 1944, the museum received the residual

trust of Laura Nelson Kirkwood, which included two very important French paintings

that had belonged to her father, William Rockhill Nelson: Monet’s Snow Effect at Argenteuil

(Fig. 12; 44-41/3), and Pissarro’s late Neo-Impressionist masterwork, Poplars, Sunset at Éragny

(1894; 44-41/2).

Painted in 1875, Monet’s snow scene is a remarkably flat composition inspired by Japanese prints, with darkly clad, silhouetted figures treading a diagonal path through heavy snow. While the Monet entered the collection without incident, Pissarro’s Poplars, painted in 1894, had many detractors who doubted its attribution; such concerns were laid to rest in 1988, when the artist’s signature and a date were revealed behind its frame.27Donald Hoffmann, "Out of the Dark and Into the Light: Pissarro Landscape ‘Found’ at Nelson," Kansas City Star, September 25, 1988. Nelson had acquired both of these paintings during a six-month trip to Europe in 1896, during which he purchased numerous works of art, including paintings and photography.28See Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 9–10. As early as 1927, R. A. Holland selected the paintings as works to be given to the budding museum; however, it was not until 1944, when Laura Nelson Kirkwood’s household goods and personal effects were finally dispersed, that they entered the collection.29Fred C. Vincent (Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trustee) to Herbert V. Jones (NAMA Trustee), December 28, 1927, NAMA curatorial files. See also Harold Woodbury Parsons to Paul Gardner, February 17, 1936, NAMA curatorial files.

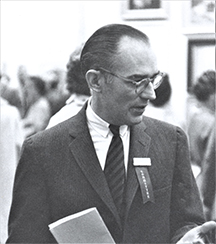

While the 1940s witnessed a temporary change of museum leadership, the 1950s represented both the end of an era and the beginning of a new one. Harold Parsons’s contract ended in 1951, and Paul Gardner retired as director in 1953, to be succeeded by Laurence Sickman, who served in the directorial role from 1953 until 1977. Sickman appointed the museum’s first curator of European art, Patrick Joseph Kelleher (Fig. 13), who remained in the position from 1953 to 1959. Among other major acquisitions in European art during his tenure, Kelleher brought in a number of important eighteenth-century French paintings. These included Joseph Duplessis’s (1725–1802) Portrait of Madame Fréret d’Héricourt, with the sitter’s growling dog (1768–69; 53-80) in 1953; Nicolas de Largillierre’s (1656–1746) imposing portrait of the Saxon Hercules, Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony and King of Poland in 1954 (ca. 1714–15; 54-35); Portrait of Diane de la Vaupalière, Comtesse de Langeron, showing the subject seated at a harp, from around 1790, which originally entered the collection as work by Jacques Louis David (1748–1825) but is now thought to be possibly by Rose-Adélaïde Ducreux (1761–1802; 54-66); the exquisite and rare oil on canvas by Franco-Swiss artist Jean Etienne Liotard (1702–1789), A Lady in Turkish Dress and Her Servant (ca. 1750; 56-3); and François Boucher’s large Landscape with a Water Mill (Fig. 14; 59-1), whose pendant, entitled The Forest, is in the collection of the Musée du Louvre. This group of pictures dramatically strengthened the museum’s eighteenth-century collections, which had not been supplemented on this level since the 1930s.

Fig. 14. François Boucher, Landscape with a Water Mill, 1740, reproduced in Jan Dickerson, “Nelson Gallery Marks 25th Year: 700 Guests at the Anniversary Observance Preview Exhibitions Which Will Open to the Public Today,” Kansas City Times, December 12, 1958, as Landscape near Beauvais

Fig. 14. François Boucher, Landscape with a Water Mill, 1740, reproduced in Jan Dickerson, “Nelson Gallery Marks 25th Year: 700 Guests at the Anniversary Observance Preview Exhibitions Which Will Open to the Public Today,” Kansas City Times, December 12, 1958, as Landscape near Beauvais

Fig. 15. Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1915–26, at the exhibition Logic of Modern Art, January 19–February 26, 1961, held at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, NAMA Archives

Fig. 15. Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1915–26, at the exhibition Logic of Modern Art, January 19–February 26, 1961, held at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, NAMA Archives

The 1950s also witnessed the second occasion on which the community signed a

petition in support of an acquisition. In 1957, the museum was presented with an

opportunity to acquire the right-hand panel of Claude Monet’s large agapanthus (water lily) triptych,

painted during the last decade of the artist’s life, between 1915 and 1926 (Fig.

15; 57-26). Late works by Monet were slow to gain currency within the art world.

Once condemned as monotonous and lacking structure, they found a new audience in

the 1950s among young American abstract painters who were mesmerized by their

horizonless depictions of nature. American critics like Clement Greenberg helped

to bridge the gap between Abstract Expressionist painters and Monet; Greenberg

wrote in a 1955 essay, “‘American-Type’ Painting,” that Monet’s late

paintings “should now begin to stand forth as a peak of revolutionary

art.”30Clement Greenberg, "‘American-Type’ Painting," in Art and Culture: Critical Essays, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 223. Capitalizing on this moment, Monet’s

son, Michel, who inherited many of his father’s late works, collaborated with

Paris gallerist Katia Granoff (1895–1989) to show Water Lilies at her gallery

in 1956, making hers one of the first galleries to show this series. Greenberg

saw the works in Paris and continued to champion them. The triptych went to

Knoedler Galleries in New York later that year, and by November 1956 the

right-hand panel went to the Nelson-Atkins for consideration of purchase.31See Day and Meyer (Murray and Young Corp.) to NAMA, November 19, 1956, NAMA curatorial file.

Nelson-Atkins Trustees were not convinced, however. Perhaps in an effort to

stress the painting’s significance for the Trustees, Patrick Kelleher included

the painting in a small exhibition entitled Some Points of View in Modern

Painting (February 10–March 10, 1957). The Trustees' decision to purchase

Water Lilies, finalized on March 20, 1957, was assisted by both Kelleher’s

input and a petition from students of the Kansas City Art Institute urging its

purchase.32The petition, dated January 7, 1957, is in the NAMA curatorial file.

In 1959, Kelleher left his curatorial post to assume the directorship of the Princeton University Art Museum. He was succeeded by Ralph Tracy (Ted) Coe, who arrived in September 1959. As the museum continued to grow, the 1960s were marked by rising costs of operations. The art market was also gaining speed, and acquisition funds did not go as far as they had previously. These developments were mediated by the rapidly changing fabric of America, which transitioned from a period of postwar opportunity toward social conflict, war, and economic downturn toward the end of the decade. The museum acquired six French works during the 1960s: three by gift and three through purchase. The most important of these was a monumental landscape by Pissarro, The Garden of Les Mathurins at Pontoise (1876; 60-38), which features a depiction of the artist’s friend and social activist, Maria Deraismes (1828–1894).33The three gifts included a pastel by Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940), The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide (1909; 60-91), given by William Inge; a street scene by Maurice Utrillo (1883–1955) entitled Street in Sannois (1912–1913; F62-46), given by the Adele R. Levy Fund; and a second street scene by twentieth-century French artist Maurice Gagni (French, active 20th century) given by Mr. and Mrs. John B. Rust, that was sold in 2008 (D64-37). The three acquisitions through purchase included the Pissarro as well as a portrait by Simon Vouet, Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes, painted around 1624, that was deaccessioned in 1993; and an intimate pastel by François Boucher, Venus with Cupid (before 1770; 66-16). The house that Maria and her sister rented in Pontoise still stands today (Fig. 16).

Although the 1960s were

marked by economic hardship, as the museum entered the 1970s it received an

unprecedented gift from a woman known affectionately as “Aunt” Helen.

This was none other than Helen Foresman Spencer (1902–1982; Fig. 17), who was

indeed Ted Coe’s aunt by marriage. In addition to endowing the library and

providing support to build the Spencer Impressionist Gallery in 1976, Helen and her

husband established the Kenneth A. and Helen F. Spencer Foundation Acquisition Fund

in 1972. This provided funds to support the acquisition of, among other things,

three important nineteenth-century French pictures: Monet’s Boulevard des Capucines (1873–1874; F72-35),

Degas’s gouache and pastel Rehearsal of the Ballet (ca. 1876; F73-30),

and Odilon Redon’s (1840–1916) pastel Vase of Flowers (ca. 1912; F76-1).

The Monet originally belonged to Mrs. Marshall Field IV of New York, who intended

to leave it to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. However, her loyalty to

then-director Thomas Hoving changed when he sold some Impressionist pictures from

the collection to raise funds for the purchase of a painting by Diego Velázquez

(Spanish, 1599–1660).34In an article entitled "Should Hoving Be De-accessioned?" John Rewald wrote that "a former benefactor of the Metropolitan" put this "magnificent painting on the market instead of willing it to the Museum. " See John Rewald, "Should Hoving Be De-accessioned?" Art in America 61 (January 1973): 29. See also Douglas Davis, "Picture Puzzle at the Met," Newsweek, January 29, 1973, 77, as cited in Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 95, 103n1. In response, Mrs. Field

placed the Monet on the market, and with funds at the ready from the Spencer gift,

the Nelson-Atkins became the proud owner of this historic early work that depicts

the view from the window of the gallery where the first Impressionist exhibition

was held in 1874. In 1973, a year after this purchase, another unprecedented

opportunity arose to acquire a Degas pastel that might otherwise have gone to the

Met. American collector Louisine Elder (later Havemeyer, 1855–1929) originally

acquired Rehearsal of the Ballet by 1877 directly from the artist, on the

recommendation of her friend Mary Cassatt (1844–1926), making it the first work by

Degas to be acquired by an American collector. It was not part of the Havemeyer

bequest to the Metropolitan Museum in 1929;35Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1961), 249–51, as cited in Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 96, 103n3.

instead, the pastel remained with the family and went to the Havemeyers' grandson,

George G. Frelinghuysen, who sold it at auction in 1965. Norton Simon acquired it

and resold the picture at auction to the Marlborough Gallery, from which the

Nelson-Atkins acquired the work in 1973 for a whopping $1,025,000, making it the

highest price paid for a work of art at that point in the museum’s history. This

record would be broken again in 1989 with the acquisition of Gustave Caillebotte’s (1848–1894), Portrait of Richard Gallo (1881; 89-35).

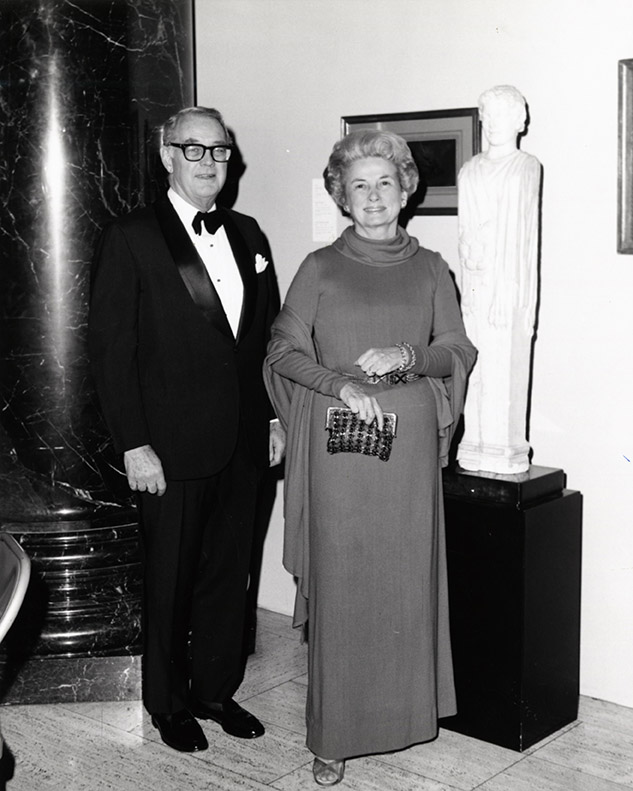

The collection of the Havemeyer family is legendary; however, they were about to be challenged by a new power couple in Kansas City, Henry and Marion Bloch (Fig. 18). Guided by Ted Coe, the Blochs bought their first Impressionist picture in 1976: Auguste Renoir’s (1841–1919) Study for “Young Girls Playing Volant,” painted around 1887 (2015.13.20). This painting launched what would become one of the last great collections of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist pictures in private hands.

In the late 1970s, an anonymous donor came forward to supply much-needed support

to the acquisition coffers. Perhaps inspired by Aunt Helen’s generosity, this

anonymous donor, who emerged from among the ranks of Society of Fellow

members—a patron group formed in 1965 by Trustees to help build and preserve

funds from the Nelson Trust for acquisitions—singlehandedly facilitated the

museum’s ability to make significant acquisitions from the late 1970s through the

early 1980s. Through an attorney, this donor asked Laurence Sickman, Ted Coe, and

the recently hired curator of Renaissance and Baroque art, Edgar Peters Bowron,

“to buy colorful paintings like that Paris view Mrs. Spencer bought for

you.”36See Annual Report to the Trustees for 1977–1978, 5, as cited in Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 99, 103n16. This request came accompanied by a

check for $1 million, followed by four additional checks of $1 million each from

August 1977 to December 1979, for a total of $5 million. While $1 million was

designated for the endowment, the remaining $4 million was directed toward

acquisitions. All gifts were received via the anonymous donor’s attorney, with the

exception of the last gift, which was delivered with dramatic flair. The donor

arranged a private meeting with Sickman on the steps of the museum on a Monday at

noon, when the museum was closed. The donor arrived in a white Cadillac and, with

a window rolled down, handed Sickman an envelope. The donor instructed him to do

what any director or curator dreams of hearing: to use the funds in any way the

museum leadership conceived.37Robert G. Kaufmann to Ralph T. Coe, August 16, 1977, NAMA Archives; "Comments of the Director," Annual Report, FY 1977–1978, NAMA Archives. Sickman, Coe, and

Bowron put the donation to good use, acquiring several extremely important French

pictures, among other treasures. Bowron acquired Jean Simeon Chardin’s (1699–1779)

Still Life with Cat and Fish (Fig. 19; F79-2);

and Coe acquired Gauguin’s Landscape in Le Pouldu (1894; F77-32),

Paul Signac’s (1863–1935) The Château Gaillard, View from My Window, Petit-Andély (1886; F78-13),

Degas’s pastel Little Milliners (Fig. 20; F79-34),

and Berthe Morisot’s (1841–1895) pastel Daydreaming (Fig. 20; F79-47),

the museum’s first purchase of a work by a French female artist.38Although the Nelson-Atkins was given its first painting by a French female artist in 1934 (Marie Laurencin’s The Boat, 1930), it later deaccessioned this work (D34-133). It was not until 1979 that the Museum purchased its first work by another French female artist, Morisot’s Daydreaming.

Fig. 19. Installation view of the Nelson-Atkins eighteenth-century gallery, 2006, with Jean Siméon Chardin’s Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728, at the left

Fig. 19. Installation view of the Nelson-Atkins eighteenth-century gallery, 2006, with Jean Siméon Chardin’s Still Life with Cat and Fish, 1728, at the left

Fig. 20. Installation view of NAMA’s galleries in 1994 with Berthe Morisot’s Daydreaming, 1877, and Edgar Degas’s Junior Milliners, 1882, and Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876, on the right-hand wall. NAMA Archives

Fig. 20. Installation view of NAMA’s galleries in 1994 with Berthe Morisot’s Daydreaming, 1877, and Edgar Degas’s Junior Milliners, 1882, and Rehearsal of the Ballet, ca. 1876, on the right-hand wall. NAMA Archives

In the 1980s, more changes were afoot, both in museum leadership and in the direction of French paintings acquisitions. Ted Coe left his post as director in 1982 and was succeeded by Marc Wilson, who remained in the role until 2010. Similarly, Roger Ward assumed the role of assistant curator of European art in 1982 following Bowron’s departure in 1981, eventually moving through the ranks to become head of the European Paintings department in 2001. The first French acquisition of the decade was the silvery landscape View of Lake Garda, painted by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) around 1865–1870 (80-44). The painting came out of the Andrew Mellon Collection and descended to Paul Mellon, who gave it to his wife’s parents, Dr. Charles Clinton and Perla Mae (née Petty) Conover of Kansas City, Missouri. It passed to their daughter Catherine Bunting (1913–1980) in 1971 and was given to the museum by her husband upon her death in 1980. This painting marks the first Corot with a solid attribution to enter the collection. The museum had acquired three pictures attributed to Corot in the 1930s—Villa with Parasol Pines (1860–1865), The Grove of Willows (about 1865–1872), and View of Subiaco, now called View in Italy (ca. 1850; 32-76)—but of these only the latter remains in the collection, and its attribution remains unknown.39See Asher Ethan Miller’s entry on the landscape previously attributed to Corot (32-76) for further details.

The first acquisition during the curatorial tenure of Roger Ward (Fig. 21) was a pair of eighteenth-century paintings by Jean-Baptiste Pater (1695–1736), Le Gouter and Les Baigneuses (1725–1730; F82-35/1 and F82-35/2), purchased with funds from Foresman Spencer’s bequest. They joined other firsts for the collection, including a pair of seascapes by Claude Joseph Vernet (1714–1789): Seaport with Antique Ruins: Morning and Coastal Harbor with a Pyramid: Evening (1751; F84-66/1 and F84-66/2), both of which came to the collection through the generosity of Sophia K. Goodman. The Vernets were commissioned by the politician and collector Louis Gabriel Peilhon (1700–1762) when the artist was living in Rome. The paintings were sent to Peilhon in Paris in time for the annual 1753 SalonSalon, the: Exhibitions organized by the French Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture (Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture) and its successor the Academy of Fine Arts (Académie des Beaux Arts), which took place in Paris from 1667 onward. and, amazingly, remained together as a pair until the Nelson-Atkins acquired them from Newhouse Galleries in New York in 1984.

The 1980s are also

characterized by a number of key deaccessions that Roger Ward made in order to make

room for major acquisitions that would fill gaps in the collection in that decade

and beyond.40Paintings deaccessioned include an oil painting by Morisot, Miss Reynolds and Julie Manet (1884; D82-21/20); an oil on cardboard by Édouard Vuillard, Mrs. Vuillard Sewing (1895; D82-21/22); a pastel by Renoir, Portrait of a Child (Lucien Daudet) (1875; D82-21/27); a pastel by Monet, Charing Cross Bridge (ca. 1899–1904; D82-21/28); a pastel by Degas, Plage à Marée Basse (1869; D82-21/29); and two paintings by Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856), Head of a Young Man in Profile to the Right (1852; DR85-8/1) and Arab Poet (1850; DR85-8/2). There were no examples of French

Romanticism before the additions of Eugène Delacroix’s (1798–1863) Christ on the Sea of Galilee (ca. 1841; 89-16),

and Théodore Géricault’s (1791–1824) The Oath of Brutus after the Death of Lucretia (ca. 1815–1816; 92-35).

The French eighteenth-century collection, while gaining strength with the addition

of the Chardin in 1979 and the pair of Vernet seascapes in 1984, still needed to

be built up around the revolutionary era. Two exquisite portraits became available,

both of which were painted by women: Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun’s (1755–1842)

masterful portrait of the raven-haired Marie Gabrielle de Gramont, Comtesse de Caderousse, who left her hair powder off (Fig. 22; 86-20);

and Adélaïde Labille-Guiard’s (1841–1927) Portrait of Joachim Lebreton (1795; 94-34).

In 1989, the museum acquired its first example by Gustave Caillebotte, the

aforementioned portrait of the artist’s friend Richard Gallo, which has the

distinction of being the most expensive acquisition by the museum to date for an

Impressionist picture.41Cited by Laura Caruso, "Caillebotte Joins Ranks at Nelson," Kansas City Star, Sunday, September 23, 1990. Featured in the seventh

Impressionist exhibition in 1882 and last seen in the public in a retrospective

held in 1894, the year of Caillebotte’s death, the painting, as well as the artist,

was relatively unknown in 1989. The museum was ahead of the curve of interest when

it acquired this work, along with its original frame designed by the artist (Fig.

23). Caillebotte retrospectives in Chicago (1995), Washington (2015), and

elsewhere have brought greater attention to his work, and consequently greater

demand. These judicious acquisitions placed the museum’s eighteenth- and

nineteenth-century collections on an entirely new level, but still there were

(and, to an extent, remain) certain key gaps in the museum’s holding of French

paintings, including Neoclassical and Academic pictures. This was remedied, in

part, in 1988, when Roger Ward “rediscovered” a painting by

William-Adolphe Bouguereau (1825–1905) in storage.42"New at the Nelson," Calendar of Events, January 1989, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2.

Fig. 23. Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881, in its original frame, likely designed by the artist

Fig. 23. Gustave Caillebotte, Portrait of Richard Gallo, 1881, in its original frame, likely designed by the artist

Fig. 24. William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869, in situ at M. B. Nelson’s home, 1932, autochrome by Frank Lauder, Kansas City Public Library, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Frank Lauder Autochrome Collection, 20004160

Fig. 24. William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Italian Woman at the Fountain, 1869, in situ at M. B. Nelson’s home, 1932, autochrome by Frank Lauder, Kansas City Public Library, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Frank Lauder Autochrome Collection, 20004160

In 1956, the museum received Bouguereau’s Italian Woman at the Fountain (1869; F88-17)

as a gift from the heirs of Mack Barnabus Nelson (1872–1950) and May Nelson (née

Milhon, 1874–1951) of Kansas City, Missouri. Mack Nelson (no relation to William

Rockhill Nelson) was a lumber baron and director of the Long-Bell Lumber Company.

These Nelsons lived in a large home at 5500 Ward Parkway, where the painting may

have remained until the house’s auction by May’s sister, Vida Frick (née Milhon,

1890–1978) of Kansas City, Missouri, on April 17, 1956 (Fig. 24). The painting

was accepted into the Nelson-Atkins Reserve collection in 1956 but remained with

Nelson’s nephew, William M. Frick (1914–2000) of Kansas City until 1974, when

it was moved to the museum.43Created in 1948 to accommodate works of lesser quality, the Nelson-Atkins Reserve Collection contained works that may have been useful for study purposes or were accepted for sale to generate funds for the acquisition of higher-quality works. A more formal policy was adopted in 1997 to limit the definition of the Reserve Collection to artworks accepted for sale within five years. While Bouguereau was

wildly popular during most of his life and appealed to early twentieth-century

captains of industry, like Nelson, the artist fell out of favor by the

mid-twentieth century, and museums were not interested in his work. As such, the

museum offered the painting for sale at Christie’s in New York in 1985, but it

failed to sell.44Nineteenth-Century European Paintings, Drawings, and Watercolors, Christie’s, New York, October 30, 1985, lot 88. It returned to the museum and

was placed in storage, where Ward reportedly found it three years later.45While Ward retained Italian Woman in the collection, he turned around and deaccessioned another painting by Bouguereau entitled Idle Thoughts (1903; D71-30/1). Originally acquired in 1971, it was sold in 1988. Funds from the proceeds of this sale went toward the acquisition of Jusepe de Ribera’s The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence (ca. 1620; 88-9).

Today, it remains on view in the galleries and continues to delight visitors with

its sensual subject matter and dazzlingly smooth application of paint.

As the museum entered the new

millennium, it set its sights on new things, including a new wing, new leadership,

an expanded European curatorial department, and new donors. When director Marc

Wilson retired in 2010 after nearly three decades at the helm, he was succeeded by

Julián Zugazagoitia, who arrived later that same year. Ian Kennedy, whose tenure

ran from 2002 to 2013, replaced Roger Ward as senior curator of European Art. He

brought on associate curators Simon Kelly from 2005 to 2010, followed by Nicole

Myers from 2010 to 2016, both specialists in nineteenth-century French art. It was

during their successive tenures that this French paintings catalogue was born.

Although there were no French acquisitions by purchase in the first decade of the

new millennium, the museum received the most significant gifts of

nineteenth-century French art in its entire history. In 2004, the museum acquired

Still-Life with Guelder Roses by Pierre Bonnard (1867–1947, 2004.12),

painted in 1892 and reworked in 1929, from Mr. and Mrs. Herman R. Sutherland (Fig.

25). The painting came out of the David-Weill collection in Neuilly-sur-Seine,

France, and was confiscated by Nazi forces in November 1943. It was later

restituted to its rightful owner by 1946 before being placed on the market in

1971 and acquired by the Sutherland family in Mission Hills, Kansas. Another

important gift came in 2014 to honor the seventy-fifth anniversary of the museum:

a vibrant pastel by Léon-Augustin Lhermitte (1844–1925), Potato Planting in Spring,

completed in 1888, from James W. Sight and Dr. Heidi Harman (Fig. 26). These

gifts were preludes to the major acquisition in 2015 of Henry and Marion Bloch’s

family collection of twenty-nine Impressionist and Post-Impressionist works of

art. While many donors wish to retain their collection intact in a separate wing,

the Bloch family wanted just the opposite. In addition to the artwork, they

donated $11.7 million to redesign the existing gallery space in order to

integrate their paintings with the permanent collection.

Lovingly built over the course of three decades, the Bloch collection of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism began in 1976 with the intimate Renoir mentioned previously (Study for “Young Girls Playing Volant”) and continued a year later with the acquisition of another Renoir, a pastel entitled Pinning the Hat (1890 or 1893; 2015.13.20). Guided more by aesthetics and heart than by a systematic desire to form a rigorously academic collection of nineteenth-century French art, Henry and Marion Bloch were nonetheless deliberate in their strategy to acquire works they loved that were approachable, just as they themselves were. They were guided in this pursuit by many individuals, including, at the forefront, former museum directors Ted Coe and Marc Wilson. Among the Bloch family’s other advisees were Gary Tinterow, who previously served as the Engelhard Curator of Nineteenth-Century, Modern, and Contemporary Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and presently is the director of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; and Roger Ward, former Louis L. and Adelaide C. Ward Senior Curator of European Art at the Nelson-Atkins Museum; as well as gallerist Susan L. Brody. Although every painting in the Bloch Collection is notable in its own right—for its academic merits and its place within each artist’s oeuvre, as carefully articulated in the essays within this volume—a few pictures stand out for their incomparable quality, relative rarity, singular provenance, or for the new dimension they add to the French collection.

All four of these categories are met with Edouard Manet’s The Croquet Party, painted around 1871 during the height of the siege of Paris (2015.13.11). The painting is intimate in scale but powerful, with vigorous brushwork that Manet deftly manipulated to convey a tempestuous sky and the strong winds that lift the flags outside the casino at Boulogne-sur-Mer, where his friends play a game of croquet. The painting at one time belonged to Gustave Caillebotte, whose will stipulated that his collection be given to the Musée du Luxembourg in Paris after his death. That museum was notified of this bequest in early March of 1894, but after eighteen months of deliberation many of the paintings, including The Croquet Party, were refused by the curatorial committee and returned to the artist’s brother, Martial Caillebotte. The painting passed by descent through Martial Caillebotte’s family until 1970, when it was briefly stolen from his daughter’s collection. It was recovered a few months later and returned to the family, and in 1973 they placed the painting with a dealer in Paris. After circulating through the marketplace, the Croquet Party was acquired by the Bloch family in 1986 through an intermediary dealer, Margo Pollins Schab of New York. The Croquet Party forms a poignant counterpart to the very late White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase (2015.13.12), also from the gift of the Bloch collection, which Manet painted in 1882 or 1883, within the last year of his life.

Although Henry and Marion Bloch most often worked with dealers, their first auction purchase was Van Gogh’s Restaurant Rispal at Asnières in 1979 (Fig. 27; 2015.13.10). Painted during the artist’s Paris period in 1887, it complements the earlier Nuenen-period Study of a Peasant’s Head (1885; 37-1) and the later Saint-Rémy–period Olive Trees (1889; 32-2) already in the Nelson-Atkins collection. Restaurant Rispal was a singularly important addition to the museum’s collection, enabling visitors to see the development of the artist’s career through three very different moments in his life. The proverbial cherry on top would be to acquire an Arles-period picture—a large portrait, or perhaps something more symbolist, from the period when the artist flirted with that approach while working alongside Gauguin and Émile Bernard (1868–1941). The museum recently acquired an important portrait by Bernard of his grandmother (2017.19), painted in 1887 when he was working alongside Van Gogh, which goes some distance to connect him within the development of a new formal artistic language later articulated by artists associated with the Nabis and Symbolist movements. This picture provides a bridge to these later movements, as do the Bloch gifts of Redon’s Vase of Flowers (ca. 1900; 2015.13.19), Edouard Vuillard’s (1868–1940) Woman in a Red Dress, or J. R. against a Window (1899–1900; 2015.13.28), and Bonnard’s large The White Cupboard (1931; 2015.13.1), Marion Bloch’s favorite painting. However, there are many additional avenues to explore—and not all of them are in France, considering the strength, quality, and availability of artwork by Belgian symbolists.

Lastly, one must consider Henri Matisse’s (1869–1954) Woman Seated before a Black Background (1942; 2015.13.13), the first painting by this artist to enter the museum’s collection. Due to early restrictions on the acquisition of modern art, Matisse, along with many other deserving modern artists, was not a consideration for the early Trustees. Despite being painted during World War II—when the artist was recovering from cancer, isolated, alone, and away from his friends and family—the painting is bursting with life. The fiery colors of the model’s wrap leap out of the black background and suggest there is hope and light amid a sea of darkness.

At the time of writing this essay, many of us are self-isolating in our homes due to COVID-19, and perhaps because of this the painting takes on even more personal meaning and relevance. Matisse reminds us in moments like this that “there are always flowers for those who want to see them.” Notwithstanding the museum’s inauspicious beginnings during the Great Depression, and the moment we currently find ourselves in, the collection of French paintings and pastels at the Nelson-Atkins is here for those who want to see it, offering beauty, hope, and light amid the current moment of darkness; freely, and accessible to all.

Notes

- Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh, Sunday, October 22, 1882; published in Leo Jansen, Hans Luijten, and Nienke Bakker, eds., Vincent van Gogh: The Letters, online edition (Amsterdam and The Hague: Van Gogh Museum and Huygens, 2009), http://vangoghletters.org/en/let274. English translation from this publication.↩

- Pierre Matisse to Alexandre Rosenberg, December 1, 1969 (PR II.22.M), The Paul Rosenberg Archives, Gift of Elaine and Alexandre Rosenberg, The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York.↩

- Nelson opened the Western Gallery of Art in 1897 with nineteen replica oil paintings of noted artworks, made in the exact scale as the originals (including the frames); more than thirty plaster casts of significant sculptures; and 450 photographs of paintings representing the most important schools of the past. William Rockhill Nelson: The Story of a Man, a Newspaper and a City (Cambridge, MA: Riverside Press, 1915), 178–79. See also Nicholas S. Pickard, "The Friends of Art of the Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum: A History," typescript, 1981, p. A6, cited in Michael Churchman and Scott Erbes, High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1933–1993 (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993), 9, 15n9.↩

- Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 11.↩

- William Rockhill Nelson’s will stipulated that his trustees be appointed by three university presidents from Missouri, Kansas, and Oklahoma (Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 11).↩

- Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (Kansas City, MO: University of Missouri Press and Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2020), 84–86. R[obert]. A[llen]. Holland was acting director of the City Art Museum of Saint Louis from 1911 to 1912 and director from 1912 to May 31, 1922. He became director of the Kansas City Art Institute in September 1924. He retired from the Kansas City Art Institute in March 1933 and had moved back to Saint Louis by October 1933. He probably relinquished his position as art advisor to NAMA around the same time. Thanks to Jenna Stout, Museum Archivist, Saint Louis Art Museum; and Elizabeth Davis, Visual and Archival Resources Specialist, Kansas City Art Institute, for their help in expanding Holland’s biography. Parsons first came to the Trustees’ attention in 1927 via a letter from Frederick A. Whiting, then director of the Cleveland Museum of Art, whom they had consulted about the new Nelson-Atkins building. See Frederic Allen Whiting to J. C. Nichols, March 8, 1927, NAMA Archives.↩

- See Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 24.↩

- Holland received $1,200 annually, whereas Parsons received $5,000 per year inclusive of travel expenses. For this fee, Parsons closely watched the New York art market from December to May and made recommendations for acquisitions. From June to November, he traveled in Europe aboard his yacht Saharet, which was based in Genoa, and he kept current on the European market. See Harold Woodbury Parsons to J. C. Nichols, August 5, 1932, as cited in Eliot Rowlands, Italian Paintings 1300–1800 (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1996), 16, 22n7.↩

- Corot, The Grove of Willows (D31-48), and Émile van Marcke (French, 1827–1890), Noonday Rest (D32-104).↩

- The other paintings include Constant Troyon (1810–1865), Cattle Pasture in the Touraine (1853; 31-47); Charles Émile Jacque (1813–1894), Sheep at the Watering Hole, (painted around 1888; 31-88); Gustave Courbet (1819–1877) Jo, The Irish Woman (ca. 1866–1868; 32-20); a Toulouse-Lautrec lithograph, The Milliner, Renée Vert (1893; F86-33); and, from Wally’s son Peter Findlay at his gallery in in New York, Edgar Degas’s Dancer Making Points (1879–1880; 2008.53).↩

- Cited in "Three Great Paintings: The Nelson Gallery Gets Added Variety in Collection," Kansas City Star, June 20, 1930.↩

- Harold Parsons to J. C. Nichols, June 2, 1931, NAMA Archives.↩

- M[inna]. K. P[owell]., "In Gallery and Studio: News and Views of the Week in Art," Kansas City Star, January 28, 1938.↩

- Letter from Dudensing Valentine, Valentine Gallery, New York City, to Parsons, April 1, 1931, NAMA curatorial files.↩

- Van Gogh was not yet a household name in 1931; however, a catalogue raisonné published in 1928 may have fueled early interest by Kansas City collectors. J.-B. de la Faille, L’Œuvre de Vincent Van Gogh: Catalogue Raisonné (Paris: Éditions G. Van Oest, 1928).↩

- Van Gogh’s works were featured in the Armory Show in 1913 and in a solo exhibition at the Montross Gallery in New York. Olive Trees was featured in the latter exhibition. Walter Feilchenfeldt felt that neither of these exhibitions made any great impact on the future collecting of Van Gogh in America. See Walter Feilchenfeldt, Van Gogh in France (London: Philip Wilson, 2013), 28–29.↩

- It is uncertain whether Miss Seachrest received a commission for items purchased on consignment. She helped Parsons select paintings at Durand-Ruel. For more information on Effie Seachrest, see The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Homage to Effie Seachrest, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, 1966).↩

- Harold Woodbury Parsons to J. C. Nichols, March 10, 1931, NAMA archives. The paintings by Alfred Sisley, Landscape (D31-78), and by Theodule Augustin Ribot (1823–1891), The Story (D31-70), had both been recently acquired and were later deaccessioned.↩

- See "Petition to purchase Van Gogh Olive Orchards," ca. April 21, 1931, NAMA Archives; and J. C. Nichols to Sybil Brelsford, July 21, 1931, NAMA Archives. See also " Pictures remaining in the Art Institute after May 20, 1932," May 20, 1932, NAMA Archives.↩

- The Detroit Institute of Arts acquired Van Gogh’s Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat in 1922 (City of Detroit Purchase, 22.13), making it the first public art institution in America to acquire a work by Van Gogh.↩

- See manuscript note from a conversation with Lighton’s son, Alfred, May 1, 1989, NAMA curatorial file.↩

- See "Mrs. Lighton’s enthusiasm and leadership," The Independent, July 23, 1973. The article is transcribed in a post of the same title dated January 30, 2011, at 1718 Holly Street, a blog dedicated to Lighton’s legacy: http://kansas-city-society-of-artists.blogspot.com/2011/01/mrs-lightons-enthusiasm-and-leadership.html. I am grateful to Meghan Gray for pointing me to this source.↩

- In an oft-recounted story from Henry Bloch, when museum director Marc Wilson was negotiating the Bloch gift of paintings, Bloch wanted to retain the Toulouse-Lautrec in his collection. Wilson asked Bloch to concede if he could prove that the drawing had been at the Nelson-Atkins in its early history. Bloch felt certain he knew the exhibition history at the Nelson-Atkins, and he took the bet. He lost, and today the drawing is in the museum’s collection.↩

- See Trustees’ minutes, January 3, 1938, in which the following was recorded: "Landscape by Cézanne and Revery by Gauguin, offered by Wildenstein. Mr. Nichols reported that after considerable negotiations, he had been able to reduce the price on the two objects to $55,000. The purchase was approved. Paid January 3rd, 1938, Voucher #472. Original price was $65,000.00."↩

- "Cezanne Landscape Year’s First Purchase at Nelson Art Gallery," Kansas City Journal-Post, March 6, 1938.↩

- Information about Ethlyne Jackson and her role at the museum is taken largely from Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 61.↩

- Donald Hoffmann, "Out of the Dark and Into the Light: Pissarro Landscape ‘Found’ at Nelson," Kansas City Star, September 25, 1988.↩

- See Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 9–10.↩

- Fred C. Vincent (Laura Nelson Kirkwood Trustee) to Herbert V. Jones (NAMA Trustee), December 28, 1927, NAMA curatorial files. See also Harold Woodbury Parsons to Paul Gardner, February 17, 1936, NAMA curatorial files.↩

- Clement Greenberg, "‘American-Type’ Painting," in Art and Culture: Critical Essays, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 223.↩

- See Day and Meyer (Murray and Young Corp.) to NAMA, November 19, 1956, NAMA curatorial file.↩

- The petition, dated January 7, 1957, is in the NAMA curatorial file.↩

- The three gifts included a pastel by Édouard Vuillard (1868–1940), The Large Fisherwoman at Low Tide (1909; 60-91), given by William Inge; a street scene by Maurice Utrillo (1883–1955) entitled Street in Sannois (1912–1913; F62-46), given by the Adele R. Levy Fund; and a second street scene by twentieth-century French artist Maurice Gagni (French, active 20th century) given by Mr. and Mrs. John B. Rust, that was sold in 2008 (D64-37). The three acquisitions through purchase included the Pissarro as well as a portrait by Simon Vouet, Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes, painted around 1624, that was deaccessioned in 1993; and an intimate pastel by François Boucher, Venus with Cupid (before 1770; 66-16).↩

- In an article entitled "Should Hoving Be De-accessioned?" John Rewald wrote that "a former benefactor of the Metropolitan" put this "magnificent painting on the market instead of willing it to the Museum. " See John Rewald, "Should Hoving Be De-accessioned?" Art in America 61 (January 1973): 29. See also Douglas Davis, "Picture Puzzle at the Met," Newsweek, January 29, 1973, 77, as cited in Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 95, 103n1.↩

- Louisine W. Havemeyer, Sixteen to Sixty: Memoirs of a Collector (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1961), 249–51, as cited in Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 96, 103n3.↩

- See Annual Report to the Trustees for 1977–1978, 5, as cited in Churchman and Erbes, High Ideals, 99, 103n16.↩

- Robert G. Kaufmann to Ralph T. Coe, August 16, 1977, NAMA Archives; "Comments of the Director," Annual Report, FY 1977–1978, NAMA Archives.↩

- Although the Nelson-Atkins was given its first painting by a French female artist in 1934 (Marie Laurencin’s The Boat, 1930), it later deaccessioned this work (D34-133). It was not until 1979 that the Museum purchased its first work by another French female artist, Morisot’s Daydreaming.↩

- See Asher Ethan Miller’s entry on the landscape previously attributed to Corot (32-76) for further details.↩

- Paintings deaccessioned include an oil painting by Morisot, Miss Reynolds and Julie Manet (1884; D82-21/20); an oil on cardboard by Édouard Vuillard, Mrs. Vuillard Sewing (1895; D82-21/22); a pastel by Renoir, Portrait of a Child (Lucien Daudet) (1875; D82-21/27); a pastel by Monet, Charing Cross Bridge (ca. 1899–1904; D82-21/28); a pastel by Degas, Plage à Marée Basse (1869; D82-21/29); and two paintings by Théodore Chassériau (1819–1856), Head of a Young Man in Profile to the Right (1852; DR85-8/1) and Arab Poet (1850; DR85-8/2).↩

- Cited by Laura Caruso, "Caillebotte Joins Ranks at Nelson," Kansas City Star, Sunday, September 23, 1990.↩

- "New at the Nelson," Calendar of Events, January 1989, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2.↩

- Created in 1948 to accommodate works of lesser quality, the Nelson-Atkins Reserve Collection contained works that may have been useful for study purposes or were accepted for sale to generate funds for the acquisition of higher-quality works. A more formal policy was adopted in 1997 to limit the definition of the Reserve Collection to artworks accepted for sale within five years.↩

- Nineteenth-Century European Paintings, Drawings, and Watercolors, Christie’s, New York, October 30, 1985, lot 88.↩

- While Ward retained Italian Woman in the collection, he turned around and deaccessioned another painting by Bouguereau entitled Idle Thoughts (1903; D71-30/1). Originally acquired in 1971, it was sold in 1988. Funds from the proceeds of this sale went toward the acquisition of Jusepe de Ribera’s The Martyrdom of Saint Lawrence (ca. 1620; 88-9).↩