![]()

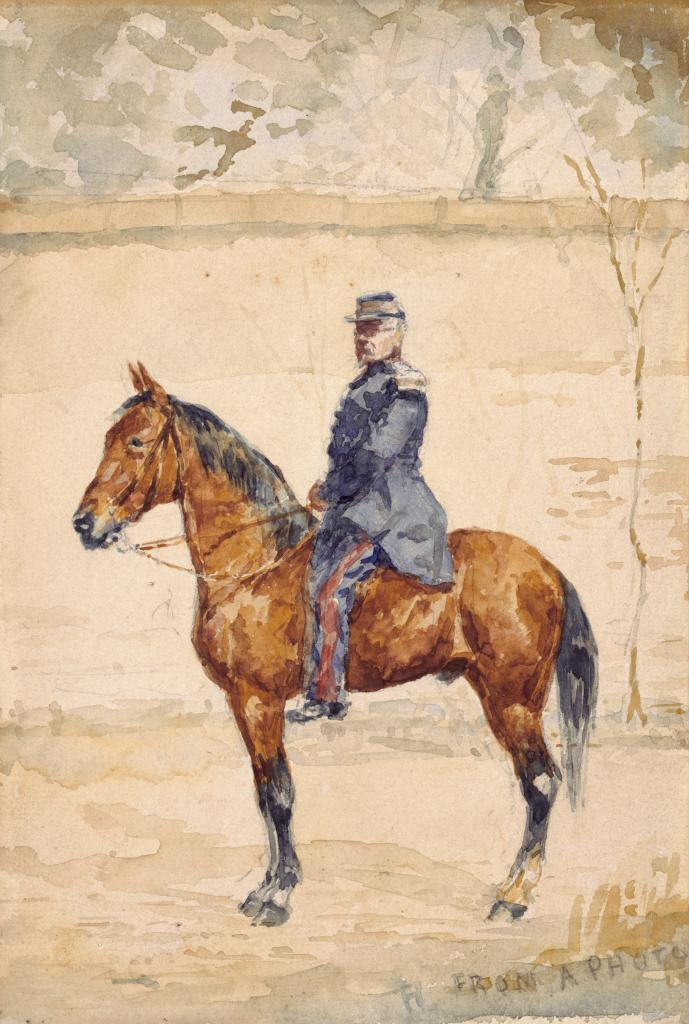

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82

| Artist | Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1864–1901) |

| Title | General Séré de Rivières |

| Object Date | 1881–82 |

| Alternate and Variant Titles | Le Général Séré de Rivières |

| Medium | Watercolor over pencil on paper |

| Dimensions (Unframed) | 10 x 7 in. (25.4 x 17.78 cm) |

| Inscription | Inscribed lower right: FROM A PHOTO |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.26 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.904.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.904.5407.

When Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec painted this modest watercolor portrait, he was still a teenager living with his mother and had only just announced his intention to become a professional artist.1Toulouse-Lautrec declared his professional ambitions in a letter to his uncle, Charles de Toulouse-Lautrec, in May 1881. See Herbert D. Schimmel, ed., The Letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 49. It would be another few months before he passed his baccalauréatbaccalauréat: A national examination taken when French students complete their secondary education, generally between the ages of fifteen and eighteen. It is the required qualification in France for anyone wishing to continue studies at the university level., exhibited his work publicly, and asserted some independence by renting a studio in Paris.2Toulouse-Lautrec passed his exams in November 1881, exhibited his work for the first time in Pau from January to March 1883, and rented a Parisian studio in October 1883. See Julia Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec: A Life (New York: Viking Penguin, 1994), 122–23, 151, 157–58. The subject matter is typical of his early period. Before entering Léon Bonnat’s (1833–1922) atelier in April 1882, Toulouse-Lautrec painted equestrian and maritime scenes almost exclusively. As he acknowledged to a friend who had expressed interest in seeing his pictures: “You have a choice between horses and sailors. The former are better.”3Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec to Etienne Devismes, January 1879, in Schimmel, Letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 28. The letters in Schimmel’s volume were translated “by divers hands.” These youthful preferences reflected the artist’s upbringing among the provincial aristocracy. From infancy, Toulouse-Lautrec had been surrounded by horses and horse enthusiasts. His father rode and hunted daily, taught his son to ride at age seven,4Toulouse-Lautrec’s riding days were short lived, however. He had to forgo this hobby during adolescence due to ongoing health problems related to a genetic disorder. See Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 116. The diagnosis of Toulouse-Lautrec’s disorder remains controversial. Many scholars think he suffered from a type of dwarfism known as pycnodysostosis, which is an autosomal recessive condition associated with bone fragility, but others disagree. For opposing opinions, see Pierre Maroteaux and Maurice Lamy, “The Malady of Toulouse-Lautrec, 1965,” in Gale B. Murray, ed., Toulouse-Lautrec: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 1992), 54–57; and Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 71. and enjoyed taking his family to the Grand Prix in Chantilly, France’s premier thoroughbred race. It was only natural, therefore, that Toulouse-Lautrec would gravitate toward hippic themes as a burgeoning artist.

This painting builds on the skills and techniques that Toulouse-Lautrec had absorbed from Princeteau. It depicts General Raymond-Adolphe Séré de Rivières (1815–95), a decorated military engineer and distant relative of the artist. Toulouse-Lautrec’s genealogical tree was quite unusual due to repeated instances of intermarriage among his immediate ancestors. Not only were his parents first cousins, but also his mother’s brother married his father’s sister. As a result, Toulouse-Lautrec was connected to General Séré de Rivières on both sides of his family. Technically speaking, they were second cousins twice removed—that is, two generations apart.9Henri Ortholan, Le général Séré de Rivières: Le Vauban de la Revanche (Paris: Bernard Giovanangeli, 2003), 38–39. However, Toulouse-Lautrec probably regarded the general as something akin to a great-uncle, for he addressed the general’s eldest son, Georges Séré de Rivières (1849–1930), as “Oncle Georges” (Uncle Georges) in both writings and conversation. Georges10From this point forward, I refer to Georges Séré de Rivières solely by his first name to avoid confusion with his father. and Toulouse-Lautrec remained close until the artist’s death. They dined together periodically,11For example, on March 1, 1877, Toulouse-Lautrec informed his grandmother: “Mama and I had dinner at my Uncle de Rivières’ house.” Georges’s sister, Hélène (1858–1942), was also in attendance. In another letter dated July 1892, Toulouse-Lautrec told his mother of plans to lunch with Georges and a woman named Suzanne Gonthier. Schimmel, Letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 19, 179. and Toulouse-Lautrec brought Georges to gatherings hosted in the mid-1890s by socialite Misia Godebska, whose husband Thadée Natanson had founded the art and literary magazine La Revue blanche.12Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 332–35. Later in the same decade, when Toulouse-Lautrec was on the brink of a mental breakdown, he impulsively asked Georges for his daughter’s hand in marriage. Georges politely refused but continued to show up for the struggling artist, visiting him when he entered a mental health facility and handling his money when he grew paranoid about family members conspiring to seize his assets.13Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 448, 479. Following weeks of erratic behavior, Toulouse-Lautrec entered a private sanatorium in Neuilly-sur-Seine run by Dr. René Semelaigne. When Toulouse-Lautrec died prematurely, Georges told a journalist: “Poor Lautrec, I did everything I could to cure him of his fatal addiction; alcoholism is a terrible disease.”14Fernand Hauser, “Le bon juge de Paris: Chez le Président Séré de Rivières,” La Presse, no. 4022 (June 4, 1903): unpaginated. “Ce pauvre Lautrec, j’ai fait tout ce que j’ai peu pour le guérir de sa fatale passion; l’alcoolisme est une terrible maladie.” Translation by Brigid M. Boyle. The extent of Toulouse-Lautrec’s relationship with Georges’s father is uncertain, but clearly the Séré de Rivières clan played an important and lasting role in his life.

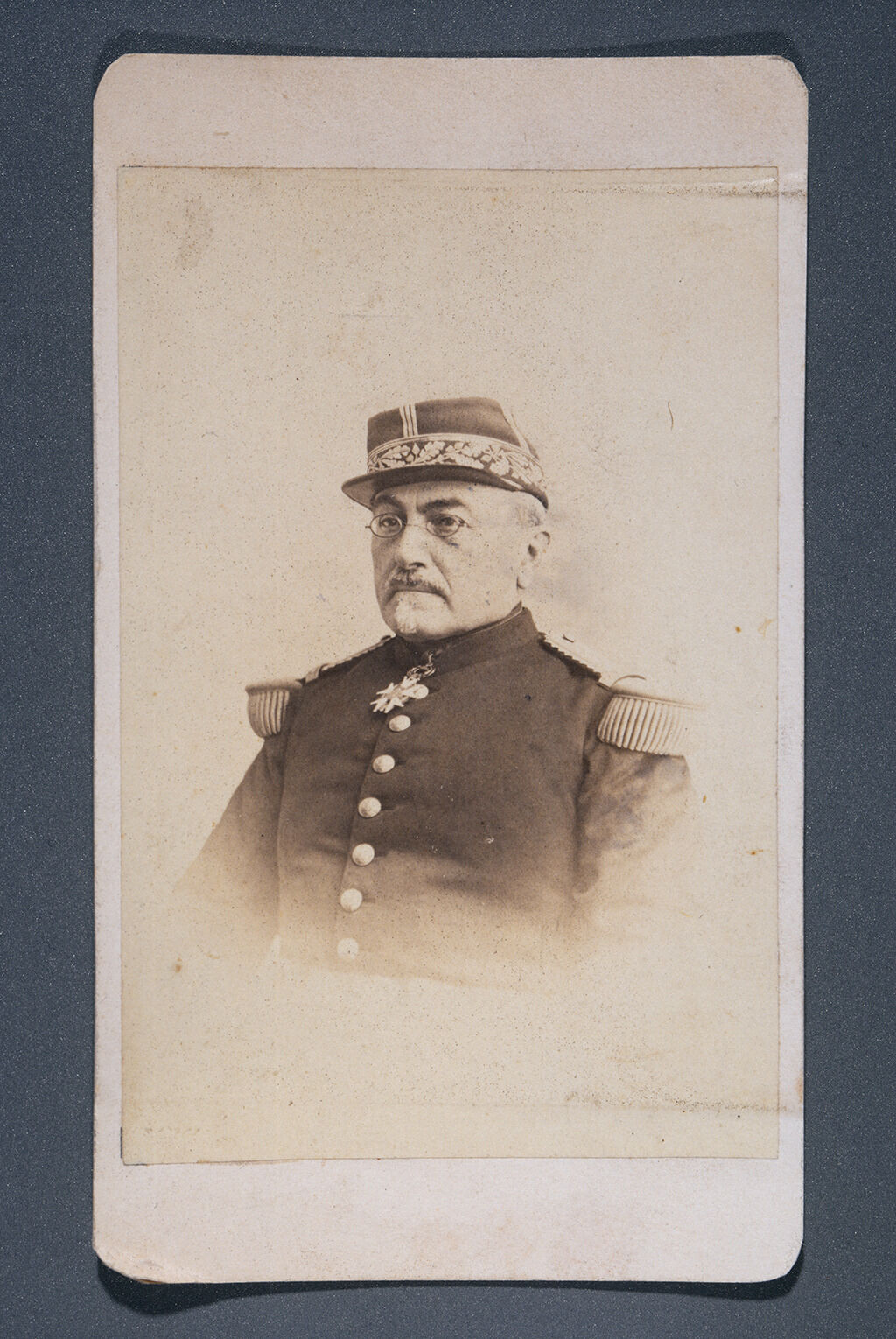

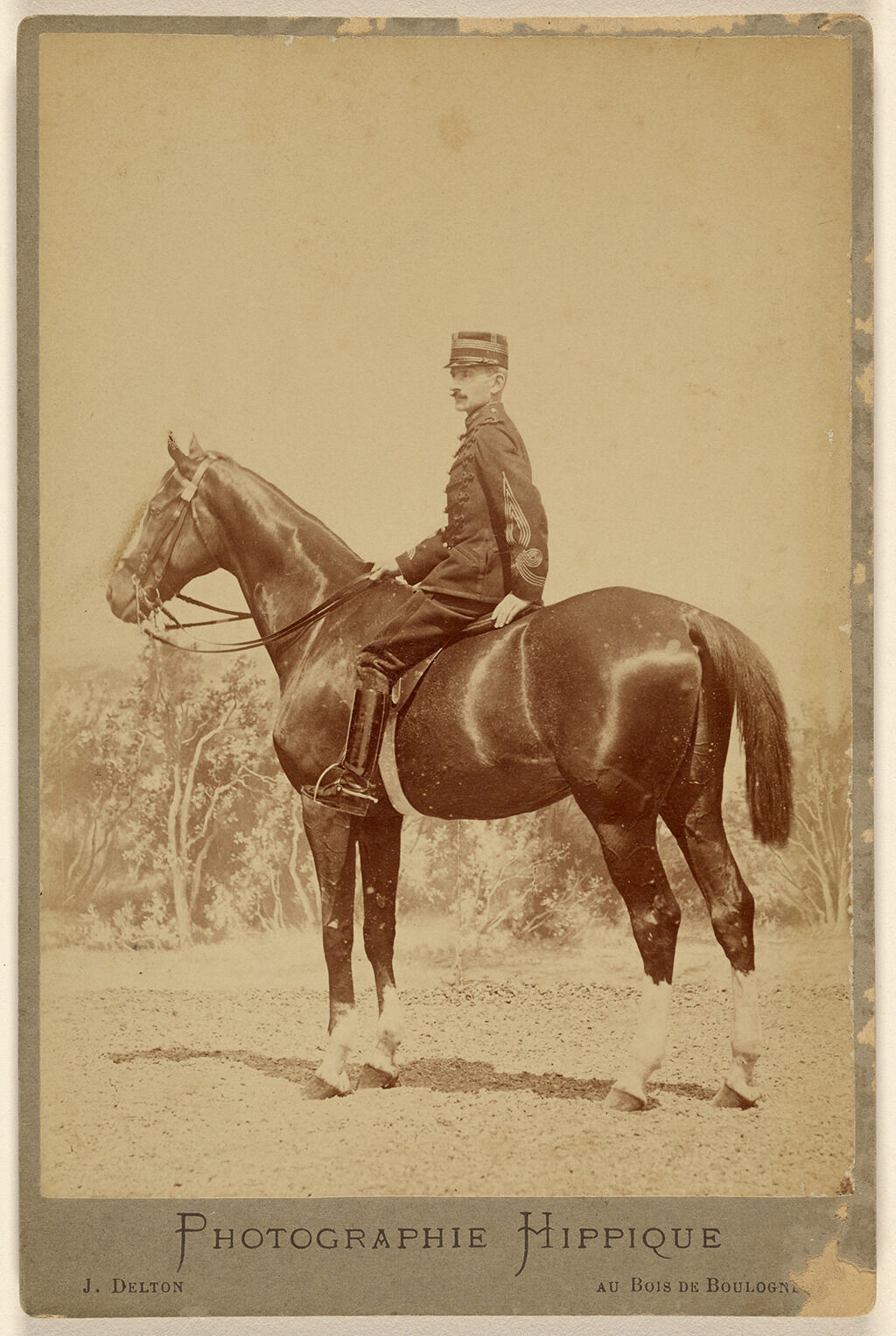

The Nelson-Atkins picture portrays General Séré de Rivières wearing his dress uniform and seated atop a chestnut horse. His proud pose matches that of his steed. Like Toulouse-Lautrec, the general was descended from nobility and born in Albi, in the south of France.15For the following biographical summary, see Henri Ortholan, “La vie et la carrière du général Raymond-Adolphe Séré de Rivières,” in Actes du colloque Séré de Rivières: Épinal 14–15–16 septembre 1995 (Paris: Association Vauban, 1999), 29–37; Guy Le Hallé, Le Système Séré de Rivières, ou le témoignage des pierres (la France et Verdun) (Louviers: Ysec, 2001), 14–16; and Jean-Denis G. G. Lepage, The Fortifications of Paris: An Illustrated History (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), 211–12. After studying at the prestigious École polytechnique in Palaiseau, he joined the military and participated in the 1841 conquest of Algeria. Over the next three decades, he oversaw engineering projects in Metz, Toulon, Perpignan, Castres, Carcassonne, Orléans, Paris, Nice, and Lyon, rising through the military hierarchy in the process. In October 1870, three months into the Franco-Prussian WarFranco-Prussian War: The war of 1870–71 between France (under Napoleon III) and Prussia, in which Prussian troops advanced into France and decisively defeated the French at Sedan. The defeat marked the end of the French Second Empire. For Prussia, the proclamation of the new German Empire at Versailles was the climax of Bismarck’s ambitions to unite Germany., Séré de Rivières was promoted to brigadier general and, shortly thereafter, given a leadership position in the Eastern Army. During the Paris CommuneParis Commune: An insurrectionary socialist government in Paris that lasted from March 18 to May 27, 1871., he assumed control of the 2nd Engineer Corps of the Versailles Army and helped retake several strategically important fortifications from the fédérésfédérés: French term for the troops who fought in support of the Paris Commune of 1871. See Paris Commune.. After the war, General Séré de Rivières led the effort to revamp France’s defense system, which their recent defeat had proven to be woefully outdated. He spearheaded the construction of 166 major forts, forty-three smaller ones, and roughly 250 batteries between 1874 and 1885. During this building frenzy the general’s likeness was painted not only by Toulouse-Lautrec but also by the more established portraitist François-Henri-Alexandre Lafond (1815–1901) (Fig. 2).16Little known today, Lafond studied under Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) and specialized in portraits, mythological scenes, and religious paintings. He served as director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Limoges from 1868 to 1874. See “Nécrologie,” Le Monde artiste, no. 28 (July 14, 1901): 449. Bespectacled, serious, and awash with medals, Séré de Rivières commands our respect in the portrait by Lafond. His most prominent decorations are those of the Legion of Honor and the Military Order of Savoy, testaments to his years of distinguished service as an army engineer. Toulouse-Lautrec omitted these marks of distinction and depicted his sitter at a further remove, producing a quieter image of the illustrious general.

Notes

-

Toulouse-Lautrec declared his professional ambitions in a letter to his uncle, Charles de Toulouse-Lautrec, in May 1881. See Herbert D. Schimmel, ed., The Letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 49.

-

Toulouse-Lautrec passed his exams in November 1881, exhibited his work for the first time in Pau from January to March 1883, and rented a Parisian studio in October 1883. See Julia Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec: A Life (New York: Viking Penguin, 1994), 122–23, 151, 157–58.

-

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec to Etienne Devismes, January 1879, in Schimmel, Letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 28. The letters in Schimmel’s volume were translated “by divers hands.”

-

Toulouse-Lautrec’s riding days were short lived, however. He had to forgo this hobby during adolescence due to ongoing health problems related to a genetic disorder. See Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 116. The diagnosis of Toulouse-Lautrec’s disorder remains controversial. Many scholars think he suffered from a type of dwarfism known as pycnodysostosis, which is an autosomal recessive condition associated with bone fragility, but others disagree. For opposing opinions, see Pierre Maroteaux and Maurice Lamy, “The Malady of Toulouse-Lautrec, 1965,” in Gale B. Murray, ed., Toulouse-Lautrec: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: Hugh Lauter Levin Associates, 1992), 54–57; and Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 71.

-

The painting was moved from Princeteau’s atelier to the Musée de Cluny on January 15, 1876. It subsequently adorned the home of American expatriate Dr. Thomas W. Evans, who hosted a fête on February 24, 1876, to celebrate the 144th anniversary of Washington’s birth. See “À travers Paris,” Le Figaro (January 12, 1876); and “Paris Local,” The American Register 8, no. 412 (February 26, 1876): 5. At the Philadelphia exhibition, the picture was titled 17th of October, 1781, Washington in reference to the British surrender at Yorktown, when General Charles Cornwallis capitulated to Washington. See International Exhibition, 1876: Official Catalogue; Department of Art, 3rd ed. (Philadelphia: John R. Nagle, 1876), p. 38, no. 193b.

-

For both letters, see Schimmel, Letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 14, 20. Odon de Toulouse-Lautrec (1842–1937) was the younger brother of the artist’s father.

-

René Princeteau, “Reminiscence of Lautrec as a Youth, ca. 1910–13,” in Murray, Toulouse-Lautrec: A Retrospective, 57.

-

Toulouse-Lautrec’s correspondence from this period often mentions Princeteau’s opinion of his work. A letter from May 1881 states: “I get as inflated as a Gambetta balloon when I think of the compliments I’ve received on [my palette]. All joking aside, I was flabbergasted. Princeteau was ecstatic.” Another dated April 17, 1882 notes: “Princeteau is still at the hotel. He is so charming to me and encouraging.” See Schimmel, Letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 49, 64.

-

Henri Ortholan, Le général Séré de Rivières: Le Vauban de la Revanche (Paris: Bernard Giovanangeli, 2003), 38–39.

-

From this point forward, I refer to Georges Séré de Rivières solely by his first name to avoid confusion with his father.

-

For example, on March 1, 1877, Toulouse-Lautrec informed his grandmother: “Mama and I had dinner at my Uncle de Rivières’ house.” Georges’s sister, Hélène (1858–1942), was also in attendance. In another letter dated July 1892, Toulouse-Lautrec told his mother of plans to lunch with Georges and a woman named Suzanne Gonthier. Schimmel, Letters of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, 19, 179.

-

Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 332–35.

-

Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 448, 479. Following weeks of erratic behavior, Toulouse-Lautrec entered a private sanatorium in Neuilly-sur-Seine run by Dr. René Semelaigne.

-

Fernand Hauser, “Le bon juge de Paris: Chez le Président Séré de Rivières,” La Presse, no. 4022 (June 4, 1903): unpaginated. “Ce pauvre Lautrec, j’ai fait tout ce que j’ai peu pour le guérir de sa fatale passion; l’alcoolisme est une terrible maladie.” Translation by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

For the following biographical summary, see Henri Ortholan, “La vie et la carrière du général Raymond-Adolphe Séré de Rivières,” in Actes du colloque Séré de Rivières: Épinal 14–15–16 septembre 1995 (Paris: Association Vauban, 1999), 29–37; Guy Le Hallé, Le Système Séré de Rivières, ou le témoignage des pierres (la France et Verdun) (Louviers: Ysec, 2001), 14–16; and Jean-Denis G. G. Lepage, The Fortifications of Paris: An Illustrated History (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2006), 211–12.

-

Little known today, Lafond studied under Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) and specialized in portraits, mythological scenes, and religious paintings. He served as director of the École des Beaux-Arts in Limoges from 1868 to 1874. See “Nécrologie,” Le Monde artiste, no. 28 (July 14, 1901): 449.

-

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 132.

-

See Œuvre Graphique de Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (Nice: Galerie des Ponchettes, 1954), unpaginated.

-

Brettell and Pissarro, Manet to Matisse, 132.

-

For Toulouse-Lautrec’s English-language skills, see Frey, Toulouse-Lautrec, 33, 53, 57, 62, 64, 69, and 384.

-

Neither the artist’s namesake museum nor the general’s descendants in Albi possess any photographs of Séré de Rivières sitting astride a horse. My thanks to Bérangère Tachenne, Musée Toulouse-Lautrec, and Gérard Alquier, Association Albi Patrimoine, for this information. Curators at the Musée de l’Armée in Paris checked their extensive photographic holdings for equestrian images of the general but found none. Alain Monferrand, President of the Association Vauban, an organization dedicated to the study of French military fortifications, kindly contacted several scholars who participated in a 1995 colloquium on General Séré de Rivières, but no one knew of an equestrian photograph that Toulouse-Lautrec could have used for reference.

-

For additional photographs of the general, including a full-length studio portrait, see Le Hallé, Le Système Séré de Rivières, 14; and Ortholan, Le général Séré de Rivières, unpaginated plates.

-

For Delton’s life and career, see Nicolas Chaudin, Le studio Delton: Miroir du temps des équipages, exh. cat. (Paris: Actes Sud, 2014), 15–44.

-

For Delton’s photo and the watercolor it inspired, see Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (Bristol: South Bank Centre, 1991), 78–79, cat. 3. The latter is inscribed “d’après photo Delton” (after Delton photo).

-

Anita Brookner, “Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions: Drawings at Messrs Wildenstein,” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 640 (July 1956): 249.

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.904.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.904.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.904.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.904.4033.

Possibly General Raymond-Adolphe Séré de Rivières (1815–95), by 1895 [1];

By descent to his granddaughter, Aline Séré de Rivières (1879–1972), Nice, by May 1955;

Purchased from Séré de Rivières by Wildenstein and Co., New York, May 1955–60 [2];

Purchased from Wildenstein by James W. Johnson (d. 1970), Cannes, 1960–December 1, 1970 [3];

Purchased at his posthumous sale, Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture, Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, December 1, 1970, lot 39, as Le Général Séré de Rivières à cheval, by Waterloo Fine Art, London, 1970 [4];

Mrs. M. J. Jacobs, by March 30, 1977 [5];

With an anonymous dealer, Tokyo, by November 14, 1990 [6];

Purchased from this dealer at Impressionist and Modern Drawings and Watercolors, Sotheby’s, New York, November 14, 1990, lot 101, through Susan L. Brody and Associates, Inc., New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1990–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] General Raymond-Adolphe Séré de Rivières (1815–95) was Toulouse-Lautrec’s second cousin twice removed. See Henri Ortholan, Le général Séré de Rivières: Le Vauban de la Revanche (Paris: Bernard Giovanangeli, 2003), 38–39.

[2] For these ownership dates, see email from Joseph Baillio, Wildenstein and Co., to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, May 21, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] The buyer was probably James Wood Johnson (1907–70) of Fort Lauderdale. Johnson married a Frenchwoman, Camille Leboutet (1896–1983), so he often spent time in France.

[4] Waterloo Fine Art operated out of Britannia Hotel (today the Biltmore Mayfair) in Grosvenor Square. It seems to have been active only during the 1970s.

[5] Mrs. M. J. Jacobs offered General Séré de Rivières at auction in 1977, but it failed to sell. See Important Impressionist and Modern Drawings and Watercolours (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, March 30, 1977), unpaginated, lot 103. The auctioneer’s book does not record Jacobs’s full name or city of residence, nor does it indicate whether General Séré de Rivières was returned to Jacobs after the auction or purchased post-sale. See email from Lucy Economakis, Sotheby’s, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 12, 2023, NAMA curatorial files.

[6] See email from Lucy Economakis, Sotheby’s, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, December 12, 2023, NAMA curatorial files.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.904.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.904.4033.

Œuvre Graphique de Toulouse-Lautrec, Galerie des Ponchettes, Nice, January 30–March 15, 1954, no. 299, as Le Général Raymond Séré de Rivières à cheval.

The Art of Drawing: XVIth to XIXth Centuries, Wildenstein and Co., London, May 9–June 16, 1956, no. 103, as General Séré de Rivières on Horseback.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 25, as General Séré de Rivières (Le Général Séré de Rivières).

Painters and Paper: Bloch Works on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 20, 2017–March 11, 2018, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.904.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, General Séré de Rivières, 1881–82,” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.904.4033.

Œuvre Graphique de Toulouse-Lautrec, exh. cat. (Nice: Galerie des Ponchettes, 1954), unpaginated, as Le Général Raymond Séré de Rivières à cheval.

The Art of Drawing: XVIth to XIXth Centuries, exh. cat. (London: Wildenstein, 1956), 26, as General Séré de Rivières on Horseback.

Anita Brookner, “Current and Forthcoming Exhibitions: Drawings at Messrs Wildenstein,” Burlington Magazine 98, no. 640 (July 1956): 249, 251, (repro.), as General Séré de Rivières.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, December 1, 1970), 24, (repro.), as Le Général Séré de Rivières à cheval.

M. G. Dortu, Toulouse-Lautrec et son œuvre (New York: Collectors Editions, 1971), no. A.193, pp. 3:496–97, (repro.), as Le Général Séré de Rivières.

Art Prices Current: A Record of Sale Prices at the Principal London, Continental, and American Auction Rooms, vol. 48, August 1970 to July 1971 (Folkestone, England: Wm. Dawsons and Sons, 1973), A83, as Le General Sere de Rivieres a [sic] cheval.

Catalogue of Important Impressionist and Modern Drawings and Watercolours (London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, March 30, 1977), unpaginated, (repro.), as Le Général Séré de Rivières.

Impressionist and Modern Drawings and Watercolors (New York: Sotheby’s, November 14, 1990), unpaginated, (repro.), as Le Général Séré de Rivières.

Henri Ortholan, Le général Séré de Rivières: Le Vauban de la Revanche (Paris: Bernard Giovanangeli, 2003), 39, 39n31.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 29, no. 6 (June 2006): 61, 63, (repro.).

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro, Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 12, 132–33, 161, (repro), as General Séré de Rivières (Le Général Séré de Rivières).

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 116, (repro.), as General Séré de Rivières.

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017): http://theartnewspaper.com/news/museums/nelson-atkins-museum-s-new-european-art-galleries-come-with-a-love-story/

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” The Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20-22].

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/.