![]()

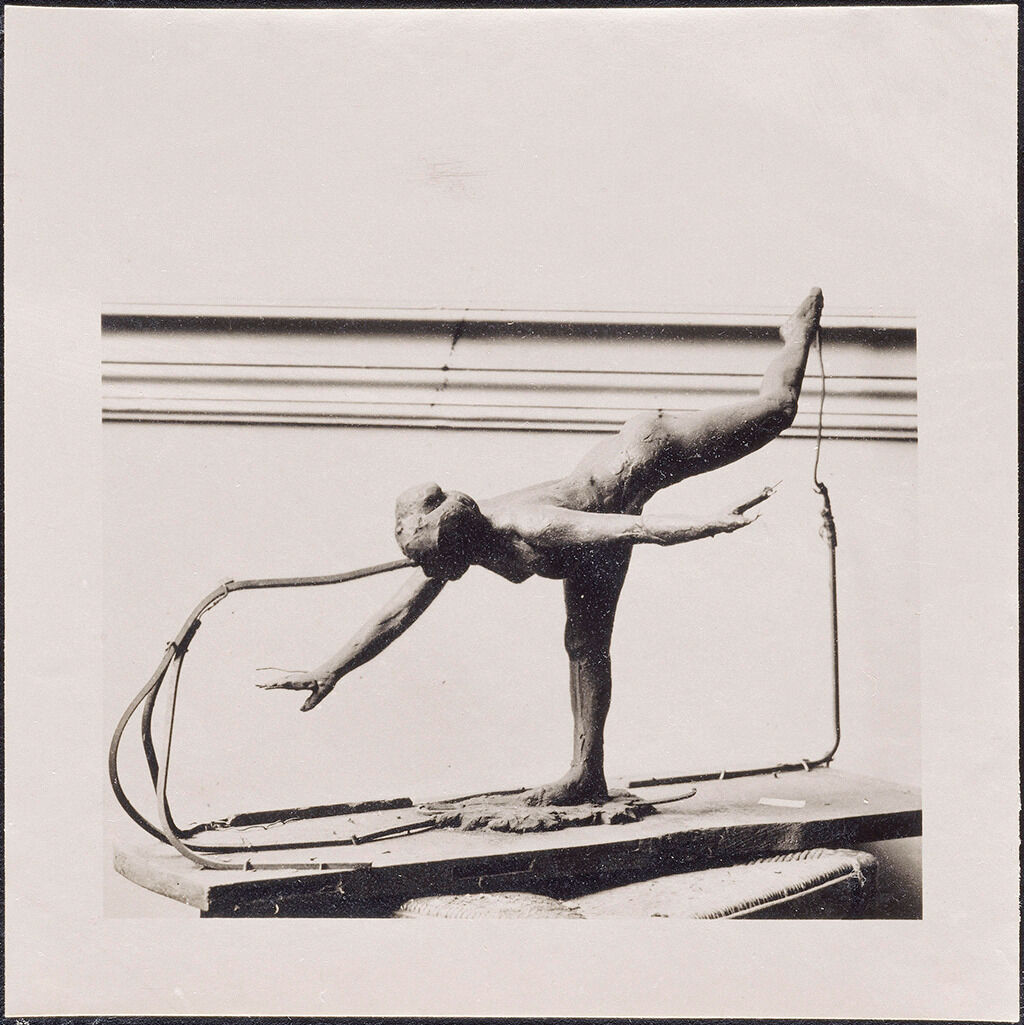

Edgar Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée), modeled 1885–90; cast 1937 or later

| Artist | Edgar Degas (French, 1834–1917) |

| Manufacturer | A.-A. Hébrard et Cie, foundry (French, 1907–37) Albino Palazzolo, founder (Italian, 1883–1973) |

| Title | Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée) |

| Object Date | modeled 1885–90; cast 1937 or later |

| Medium | Copper alloy |

| Dimensions | 17 7/8 × 22 × 11 1/2 in. (45.4 × 55.9 × 29.2 cm) |

| Inscription | Inscribed on the top left side of the base, on the figure’s proper right side: Degas Stamped on the top right side of the base, on the figure’s proper left side: 60/M; Stamped on the top right side of the base, to the right of the edition number, on the figure’s proper left side: Cire / Perdue / A. A. Hébrard |

| Credit Line | The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.8 |

Catalogue Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” catalogue entry in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.902.5407.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” catalogue entry. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.902.5407.

Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée) is a posthumous cast in copper alloy of a sculpture that Impressionist artist Edgar Degas modeled primarily in beeswax around 1885–90.1Various modeling dates have been proposed. John Rewald, the first scholar to study Degas’s sculptures seriously, estimated 1882–95; Michèle Beaulieu suggested an earlier time frame of 1877–83; Charles Millard postulated 1885–90 in his monograph; Gary Tinterow favored a later period of creation, 1892–96; and, most recently, a team of art historians and conservators including Sara Campbell, Richard Kendall, Daphne S. Barbour, and Shelley G. Sturman advocated for 1885–90, echoing Millard. We have adopted the latter date range, since it is supported by the latest scientific research. See John Rewald, ed., Degas: Works in Sculpture; A Complete Catalogue, trans. John Coleman and Noel Moulton (New York: Pantheon Books, 1944), 15; Michèle Beaulieu, “Les sculptures de Degas: Essai de chronologie,” La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France 19, no. 6 (1969): 374; Charles Millard, The Sculpture of Edgar Degas (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 24; Gary Tinterow, “Cats. 372–73, First Arabesque Penchée,” in Jean Sotherland Boggs, ed., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 586; and Sara Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 365. It is one of at least twenty-one editions of this particular dancer, today scattered across the globe, that Italian founderfounder: One who casts metal, or makes articles of cast metal. Albino Palazzolo manufactured in the decades following Degas’s death in 1917. The complex story of how these and other Degas sculptures were created, dispersed, and received by the general public has been greatly refined in recent years thanks to groundbreaking technical studies and archival research. This essay summarizes those findings and explores their implications for the Nelson-Atkins cast.

When Degas passed away at the age of eighty-three, he left behind a cache of working sculptures in varying conditions and states of completeness. The vast majority were crafted from wax and plastileneplastilene: A sulfur-rich, non-drying modeling clay invented in the late nineteenth century and still in use today., malleable materials favored by Degas because they allowed him flexibility to modify the poses of his human and animal figures.2For an overview of the plastilenes that were commercially available during Degas’s lifetime, see Barbara H. Berrie, Suzanne Quillen Lomax, and Michael Palmer, “Surface and Form: The Effect of Degas’ Sculptural Materials,” in Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Daphne S. Barbour, and Shelley G. Sturman, Edgar Degas Sculpture (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2010), 47. At the behest of Degas’s heirs,3Degas was unmarried and childless, so his brother René Degas and the four surviving children of his sister, Marguerite Fevre, inherited his estate. two of the artist’s former dealers, Paul Durand-Ruel and Ambroise Vollard, inventoried these models from December 1917 to January 1918 and hired a photographer to document them. The photographer, known only as Gauthier, photographed fifty-three of the seventy-three wax models that were ultimately selected for casting.4Most likely, Degas’s heirs and former dealers decided to cast an additional twenty models after Gauthier had already been compensated for his photography services. Regrettably, the model for the Nelson-Atkins cast was among those that were present in Degas’s studio but somehow eluded Gauthier’s camera.5For a transcription of the inventory and a list of the wax models featured in and missing from Gauthier’s photos, see Anne Pingeot, Degas: Sculptures (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991), 192–94. The dealers waited anxiously while Degas’s relatives deliberated which foundry would translate the artist’s wax models into more permanent media. As Durand-Ruel’s eldest son and business partner, Joseph, confided to Degas’s artist friend Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) on February 18, 1918: “If they are not cast soon by an expert, they will crumble completely into worthless pieces.”6Joseph Durand-Ruel to Mary Cassatt, February 18, 1918, cited in Anne Pingeot, “Degas and His Casting,” in Joseph S. Czestochowski and Anne Pingeot, Degas Sculptures: Catalogue Raisonné of the Bronzes, exh. cat. (Memphis: International Arts, 2002), 28. Three months later, on May 13, 1918, Degas’s family awarded Adrien-Aurélien Hébrard’s (1865–1937) foundry the right to reproduce Degas’s sculptures, with the stipulation that they receive 25 percent of net sales. The contract specified that Hébrard could create twenty-two casts from each wax model—one for Degas’s heirs, one for the foundry, and twenty saleable editions.7Pingeot, Degas: Sculptures, 194. However, as discussed below, Hébrard deviated in significant ways from these terms.

Due to World War I, casting did not begin until 1919. Hébrard entrusted this immense project to Palazzolo, his longtime director. An Italian expatriate, Palazzolo had cut his teeth at a foundry in Milan before moving to Paris in 1903 and joining Hébrard’s team.8For Palazzolo’s biography, see Jean Adhémar, “Before the Degas Bronzes,” trans. Margaret Scolari, ARTnews 54, no. 7, pt. 1 (November 1955): 34–35, 70. For a photograph of Palazzolo overseeing the casting of Degas’s sculptures, see Daphne S. Barbour, “Degas’s Wax Sculptures from the Inside Out,” Burlington Magazine 134, no. 1077 (December 1992): 798. Palazzolo was particularly skilled at a variation of the lost-wax processlost-wax process: A method of casting that involves making a model with a wax surface, enclosing the model in a mold, melting the wax out, and pouring molten metal between the core and mold. Also known by its French name, cire perdue. that, counterintuitively, preserved rather than destroyed the original wax models by making expendable duplicate waxes that were melted in their stead.9For a step-by-step breakdown and helpful diagrams of this complicated process, see Daphne Barbour and Shelley Sturman, “The Modèle Bronzes,” in Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum, 53–58. Palazzolo used this technique for the Degas commission, thus saving Degas’s autograph models for posterity.10Only four of Degas’s original wax models did not survive the casting. See Barbour, “Degas’s Wax Sculptures from the Inside Out,” 799. Unbeknownst to the family, at Hébrard’s urging Palazzolo began by creating unauthorized master casts of Degas’s figurines, which served as the matrix for all subsequent casts. These extracontractual sculptures are usually referred to as the “modèles,” in reference to the marks inscribed on their bases, or the “master bronzes”—even though, strictly speaking, they were cast not in bronze but brass, itself an alloy of copper, zinc, and tin.11The existence of the modèles remained a foundry secret until 1976, when Hébrard’s heirs exhibited them en masse at Lefevre Gallery, London, and subsequently sold them to collector Norton Simon. See The Complete Sculptures of Degas, exh. cat. (London: Lefevre Gallery, 1976). Today the entire set belongs to the Norton Simon Art Foundation in Pasadena, California. Regarding the medium, see Shelley G. Sturman and Daphne Barbour, “Degas’ Bronzes Analyzed,” in Edgar Degas Sculpture, 26. Once the modèles were finished, Palazzolo cast the first complete saleable edition of Degas’s sculptures, known as set A, which Hébrard exhibited from May to June 1921 and then sold to New York collector Louisine Havemeyer.12See Exposition des sculptures de Degas, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie A.-A. Hébrard, 1921).

Initially, scholars believed that Palazzolo had completed all twenty-two heir-approved editions between 1919 and 1921. John Rewald said as much in his 1944 catalogue raisonné of Degas’s sculptural oeuvre.13Rewald, Degas: Works in Sculpture, 14. Later, Jean Adhémar, on the basis of information received from Palazzolo himself, proposed that casting had continued until 1932.14Adhémar, “Before the Degas Bronzes,” 70. However, even this more conservative timeline proved inaccurate when, in 1991, Anne Pingeot published excerpts from Hébrard’s archives. The foundry was liquidated in 1937, so their records date to 1936 and earlier. Pingeot discovered that Hébrard’s ledgers recorded sales of 567 Degas casts by 1936—far fewer than the 1,606 sculptures permitted by the contract with Degas’s heirs (twenty-two editions times seventy-three figurines).15For the Hébrard archives, see Pingeot, Degas: Sculptures, 153–97. This discrepancy reflects the foundry’s efforts to protect itself from financial loss. Rather than risk overproduction of unpopular figurines, Hébrard preferred—with some exceptions, including the aforementioned set A—to cast Degas’s sculptures piecemeal and in response to consumer demand, rather than as complete editions.

Additional casting information came to light in 1995, when Sara Campbell published an exhaustive catalogue of every known Degas cast, which at the time totaled 1,215 sculptures. This tally excluded the modèles but accounted for the serialized casts (lettered A to T), the heirs’ casts (inscribed “HER.D” for héritiers Degas, or “Degas heirs”), and the foundry’s casts (inscribed “HER” for héritiers, even though Hébrard was not among the artist’s heirs), as well as an assortment of unsanctioned casts (some inscribed “AP” for Albino Palazzolo, some unlettered).16Sara Campbell, “A Catalogue of Degas’ Bronzes,” Apollo 142, no. 402 (August 1995): 11–48. Campbell has since released an updated inventory that identifies still more casts.17Sara Campbell, “Inventory of Serialized Bronze Casts,” in Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum, 501–57. The painstaking research of Pingeot and Campbell leaves no doubt that Palazzolo went on casting copper alloy sculptures and stamping them with both the Degas estate cachet and the Hébrard foundry mark long after the Hébrard foundry had closed. According to Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Palazzolo opened his own facility soon after Hébrard’s liquidation and remained active as a founder through the 1950s.18Suzanne Glover Lindsay, “Degas’ Sculpture After His Death,” in Lindsay, Barbour, and Sturman, Edgar Degas Sculpture, 18.

Fig. 3. X-radiograph of Fig. 2. © Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, Paris

Fig. 3. X-radiograph of Fig. 2. © Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France, Paris

Fig. 4. Gauthier, inventory photograph of Edgar Degas’s Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée) (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1999.80.10) before its external armature was removed, 1917–18, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, ODO 1996-56-4657. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Repro-photo: Franck Raux

Fig. 4. Gauthier, inventory photograph of Edgar Degas’s Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée) (National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 1999.80.10) before its external armature was removed, 1917–18, Musée d’Orsay, Paris, ODO 1996-56-4657. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Repro-photo: Franck Raux

When Hébrard mounted the inaugural exhibition of Degas’s figurines in 1921, viewers were transfixed by his sculptural renderings of ballerinas. The critic Georges de Traz, known as François Fosca, praised them in a review for the monthly periodical L’Art et les artistes, saying: “[T]he artist was determined to capture the diverse poses of classical dance, with the precision of a ballet master and the science of an anatomist.”27François Fosca [Georges de Traz], “L’Actualité: Degas sculpteur,” L’Art et les artistes 3, no. 18 (June 1921): 373. “[L]’artiste a tenu à retracer les diverses attitudes de la danse classique, avec la précision d’un maître de ballet et la science d’un anatomiste.” All translations from the French are by Brigid M. Boyle. Included in Hébrard’s exhibition was cast A of sculpture no. 60. The Nelson-Atkins figurine (cast M of no. 60) probably made its public debut three decades later, in postwar Amsterdam. Willem Sandberg, director of the Stedelijk Museum, organized a Degas exhibition there from February 8 to March 24, 1952. Unfortunately, since his retrospective came on the heels of another Degas show at the Kunstmuseum Bern, Sandberg struggled to secure loans, especially of Degas’s sculpture. In early January 1952, a few weeks before the scheduled opening, he wrote in desperation to his co-organizer, Parisian gallerist Max Kaganovitch (1891–1978): “After Reed’s [sic] refusal in particular, what should we do to have enough important Degas sculptures? I am sending you this heartfelt appeal at top speed, hoping that you might help us.”28Willem Sandberg to Max Kaganovitch, early January 1952, 30041 Archief van het Stedelijk Museum, Tentoonstelling Edgar Degas, 1951–52, 3496 Correspondentie K–Z (hereafter ASM 3496). “Après le refus de Reed [sic] surtout, qu’est-ce que nous devons faire pour avoir assez de sculptures importante? Je vous envoie ce cri de cœur de toute vitesse en espérant que vous pourriez nous aider.” The “Reed” mentioned by Sandberg was the London dealer A. J. McNeill Reid, who earlier that week had written that his gallery Alex Reid and Lefèvre could not send any Degas sculptures to Amsterdam because they had already found buyers for much of their stock. See A. J. McNeill Reid to Willem Sandberg, January 7, 1952, ASM 3496. Fortunately, Kaganovitch came through. Of the thirty-nine figurines ultimately exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum in 1952, all but one came from Kaganovitch’s own stock.29See Edgar Degas, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1952), unpaginated, nos. 106–44. The only sculptural work not supplied by Kaganovitch was no. 115, which was on loan from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, as evidenced by a scrap of paper in the Stedelijk Museum’s archives that reads “Kaganovitch. 99 Boulevard Raspail, Paris. 6. / N° 106 tot 144 (behalve N° 115, Boymans)” (Kaganovitch. 99 Boulevard Raspail, Paris. 6th arrondissement. / Nos. 106 to 144 [except no. 115, Boijmans]). See ASM 3496. No. 140, Danseres, naar rechtervoet kijkend (Dancer, looking at her right foot), was a cast of sculpture no. 60. While it has not been possible to identify this cast definitively, Kaganovitch owned the Nelson-Atkins figurine before the Juvilers and almost certainly sold it to them, so it is highly probable that the Kansas City Grande Arabesque was the one displayed in Amsterdam as no. 140.30The catalogue for the Juvilers’ collection sale says “From the Galerie Max Kaganovitch, Paris” in the entry for Grande Arabesque, suggesting a direct transfer. See Notable Modern Paintings, 5.

At first glance, his ballet dancers are delightful, delicate creatures, the embodiment of grace and expression of joy in beautiful movements. We see them as such in his work, especially in his sculptures, which are here in a considerable quantity: studies of poses, with the movement exquisitely and charmingly rendered. However, Degas also understood the exhausting labor that precedes a performance, the wretched humanity of these figures, and this he also captured, sometimes in stark contrast to the beauty that was conjured on stage.33“Degas: bitterhead en schoonheid,” Algemeen Dagblad 73, no. 40 (February 16, 1952): 5. “Zijn balletmeisjes zijn voor het oog verrukkelijke, lichte wezentjes, de belichaming van de gratie en de vreugde in de schone beweging. We vinden hen als zodanig in zijn werk, in zijn beeldhouwwerk vooral, dat hier in ruime mate aanwezig is: studies van standjes, met de beweging voortreffelijk en charmant vastgelegd. Maar Degas kende ook de uitputende arbeid, die aan de dans voorafgaat, de povere menselijkheid van die figuurtjes, en deze legde hij ook vast, soms in tegenstelling tot wat er op het podium aan schoonheid wordt voorgetoverd.”

For this museum visitor, Degas’s candor truly distinguished his sculpted dancers. He depicted the consummate skill and elegance of ballerinas without idealizing them, and he also acknowledged their incessant toil. Perhaps to emphasize this point, the anonymous critic titled his review “Degas: Bitterhead en schoonheid” (Degas: Harshness and Beauty), implying that the Impressionist had struck the right balance between them in his oeuvre.

More than a century has elapsed since Hébrard began casting Degas’s wax models, yet interest in Degas’s sculptural production remains stronger than ever. As the lone example of Degas’s three-dimensional work in the Nelson-Atkins collection, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée) offers a valuable opportunity to understand better the casting, distribution, and reception of his figurines.

Notes

-

Various modeling dates have been proposed. John Rewald, the first scholar to study Degas’s sculptures seriously, estimated 1882–95; Michèle Beaulieu suggested an earlier time frame of 1877–83; Charles Millard postulated 1885–90 in his monograph; Gary Tinterow favored a later period of creation, 1892–96; and, most recently, a team of art historians and conservators including Sara Campbell, Richard Kendall, Daphne S. Barbour, and Shelley G. Sturman advocated for 1885–90, echoing Millard. We have adopted the latter date range, since it is supported by the latest scientific research. See John Rewald, ed., Degas: Works in Sculpture; A Complete Catalogue, trans. John Coleman and Noel Moulton (New York: Pantheon Books, 1944), 15; Michèle Beaulieu, “Les sculptures de Degas: Essai de chronologie,” La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France 19, no. 6 (1969): 374; Charles Millard, The Sculpture of Edgar Degas (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 24; Gary Tinterow, “Cats. 372–73, First Arabesque Penchée,” in Jean Sotherland Boggs, ed., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 586; and Sara Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 365.

-

For an overview of the plastilenes that were commercially available during Degas’s lifetime, see Barbara H. Berrie, Suzanne Quillen Lomax, and Michael Palmer, “Surface and Form: The Effect of Degas’ Sculptural Materials,” in Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Daphne S. Barbour, and Shelley G. Sturman, Edgar Degas Sculpture (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2010), 47.

-

Degas was unmarried and childless, so his brother René Degas and the four surviving children of his sister, Marguerite Fevre, inherited his estate.

-

Most likely, Degas’s heirs and former dealers decided to cast an additional twenty models after Gauthier had already been compensated for his photography services.

-

For a transcription of the inventory and a list of the wax models featured in and missing from Gauthier’s photos, see Anne Pingeot, Degas: Sculptures (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991), 192–94.

-

Joseph Durand-Ruel to Mary Cassatt, February 18, 1918, cited in Anne Pingeot, “Degas and His Casting,” in Joseph S. Czestochowski and Anne Pingeot, Degas Sculptures: Catalogue Raisonné of the Bronzes, exh. cat. (Memphis: International Arts, 2002), 28.

-

Pingeot, Degas: Sculptures, 194.

-

For Palazzolo’s biography, see Jean Adhémar, “Before the Degas Bronzes,” trans. Margaret Scolari, ARTnews 54, no. 7, pt. 1 (November 1955): 34–35, 70. For a photograph of Palazzolo overseeing the casting of Degas’s sculptures, see Daphne S. Barbour, “Degas’s Wax Sculptures from the Inside Out,” Burlington Magazine 134, no. 1077 (December 1992): 798.

-

For a step-by-step breakdown and helpful diagrams of this complicated process, see Daphne Barbour and Shelley Sturman, “The Modèle Bronzes,” in Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum, 53–58.

-

Only four of Degas’s original wax models did not survive the casting. See Barbour, “Degas’s Wax Sculptures from the Inside Out,” 799.

-

The existence of the modèles remained a foundry secret until 1976, when Hébrard’s heirs exhibited them en masse at Lefevre Gallery, London, and subsequently sold them to collector Norton Simon. See The Complete Sculptures of Degas, exh. cat. (London: Lefevre Gallery, 1976). Today the entire set belongs to the Norton Simon Art Foundation in Pasadena, California. Regarding the medium, see Shelley G. Sturman and Daphne Barbour, “Degas’ Bronzes Analyzed,” in Edgar Degas Sculpture, 26.

-

See Exposition des sculptures de Degas, exh. cat. (Paris: Galerie A.-A. Hébrard, 1921).

-

Rewald, Degas: Works in Sculpture, 14.

-

Adhémar, “Before the Degas Bronzes,” 70.

-

For the Hébrard archives, see Pingeot, Degas: Sculptures, 153–97.

-

Sara Campbell, “A Catalogue of Degas’ Bronzes,” Apollo 142, no. 402 (August 1995): 11–48.

-

Sara Campbell, “Inventory of Serialized Bronze Casts,” in Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum, 501–57.

-

Suzanne Glover Lindsay, “Degas’ Sculpture After His Death,” in Lindsay, Barbour, and Sturman, Edgar Degas Sculpture, 18.

-

For the full list of casts and their whereabouts, see the Related Works collapsible section of this catalogue entry. No HER, HER.D, or AP editions have yet surfaced for sculpture no. 60, but it is possible that they, too, were cast.

-

Joseph S. Czestochowski, “Degas’s Sculptures Re-examined: The Marketing of a Private Pursuit,” in Czestochowski and Pingeot, Degas Sculptures, 24n23. The first sculpture cast from the M series was no. 22, which Hébrard sold to Norwegian dealer Walther Halvorsen (1887–1972) on March 1, 1924. See Czestochowski and Pingeot, Degas Sculptures, 165. As of 2009, when Campbell published her revised inventory of Degas casts, thirty-four sculptures from the M series had been located; the remaining thirty-nine may never have been cast.

-

The Juvilers sold Grande Arabesque at auction that year. See Notable Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture. . . . From the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Adolphe A. Juviler, New York, and Palm Beach, Sold by Their Order (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, October 25, 1961), 5.

-

France Drilhon, Sylvie Colinart, and Anne Tassery-Lahmi, “Cat. 66: Edgar-Hilaire Degas, Danseuse: Grande Arabesque, 3e temps, première étude,” in Jean-René Gaborit and Jack Ligot, eds., Sculptures en cire de l’ancienne Egypte à l’art abstrait (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1987), 232.

-

The rickety nature of Degas’s armatures was common knowledge among the artist’s friends and colleagues. See Paul-André Lemoisne, “Les Statuettes de Degas,” Art et decoration 31, no. 214 (September–October 1919): 113.

-

Shelley G. Sturman, “Cat. 32: Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” in Lindsay, Barbour, and Sturman, Edgar Degas Sculpture, 209–12.

-

Sturman, “Cat. 32: Grande Arabesque, Third Time,” 212n8. Sturman is head of objects conservation at the National Gallery of Art.

-

Tinterow, “Cats. 372–73, First Arabesque Penchée,” 586.

-

François Fosca [Georges de Traz], “L’Actualité: Degas sculpteur,” L’Art et les artistes 3, no. 18 (June 1921): 373. “[L]’artiste a tenu à retracer les diverses attitudes de la danse classique, avec la précision d’un maître de ballet et la science d’un anatomiste.” All translations from the French are by Brigid M. Boyle.

-

Willem Sandberg to Max Kaganovitch, early January 1952, 30041 Archief van het Stedelijk Museum, Tentoonstelling Edgar Degas, 1951–1952, 3496 Correspondentie K–Z (hereafter ASM 3496). “Après le refus de Reed [sic] surtout, qu’est-ce que nous devons faire pour avoir assez de sculptures importante? Je vous envoie ce cri de cœur de toute vitesse en espérant que vous pourriez nous aider.” The “Reed” mentioned by Sandberg was the London dealer A. J. McNeill Reid, who earlier that week had written that his gallery Alex Reid and Lefèvre could not send any Degas sculptures to Amsterdam because they had already found buyers for much of their stock. See A. J. McNeill Reid to Willem Sandberg, January 7, 1952, ASM 3496.

-

See Edgar Degas, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1952), unpaginated, nos. 106–44. The only sculptural work not supplied by Kaganovitch was no. 115, which was on loan from the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, as evidenced by a scrap of paper in the Stedelijk Museum’s archives that reads “Kaganovitch. 99 Boulevard Raspail, Paris. 6. / N° 106 tot 144 (behalve N° 115, Boymans)” (Kaganovitch. 99 Boulevard Raspail, Paris. 6th arrondissement. / Nos. 106 to 144 [except no. 115, Boijmans]). See ASM 3496.

-

The catalogue for the Juvilers’ collection sale says “From the Galerie Max Kaganovitch, Paris” in the entry for Grande Arabesque, suggesting a direct transfer. See Notable Modern Paintings, 5.

-

In addition to the article in Nieuwe Haarlemsche courant (see Fig. 5), other exhibition reviews featuring photographs of Little Dancer Aged Fourteen include: Jan Engelman, “In de cuisine van Degas: Zijn onvrede met het bereikte,” De Tijd, no. 34970 (February 23, 1952): 3; and J. W., “Edgar Degas, een zoeker,” Arnhemsche Courant, no. 19721 (March 8, 1952): unpaginated.

-

“Edgar Degas, meester der beweging,” Het Binnenhof, no. 2062 (February 16, 1952): 5. “Zijn danseressen en vrouwen zijn wezenlijke danseressen en vrouwen. Zij hebben gratie, maar zij zijn niet gracieus in de gebruikelijke betekenis.” I am grateful to Joëlla van Donkersgoed, University of Luxembourg, for assisting with the Dutch-English translations.

-

“Degas: bitterhead en schoonheid,” Algemeen Dagblad 73, no. 40 (February 16, 1952): 5. “Zijn balletmeisjes zijn voor het oog verrukkelijke, lichte wezentjes, de belichaming van de gratie en de vreugde in de schone beweging. We vinden hen als zodanig in zijn werk, in zijn beeldhouwwerk vooral, dat hier in ruime mate aanwezig is: studies van standjes, met de beweging voortreffelijk en charmant vastgelegd. Maar Degas kende ook de uitputende arbeid, die aan de dans voorafgaat, de povere menselijkheid van die figuurtjes, en deze legde hij ook vast, soms in tegenstelling tot wat er op het podium aan schoonheid wordt voorgetoverd.”

Documentation

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

Provenance

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

Probably with Galerie Max Kaganovitch, Paris, by February 8, 1952 [1];

Probably purchased from Kaganovitch by Adolphe Adam (1894–1968) and Katherine (née Nalinska, 1897–1971) Juviler, New York and Palm Beach, by October 25, 1961 [2];

Purchased at their sale, Notable Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture: Bonnard, Braque, Buffet, Cézanne, Chagall, Degas, Dufy, Maillol, Matisse, Moore, Picasso, Renoir, Rouault, Soutine, Utrillo, and Vuillard; From the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Adolphe A. Juviler, New York, and Palm Beach, Sold by Their Order, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, October 25, 1961, lot 9, as Grande Arabesque, Third Time, by Edgardo Acosta Gallery, Beverly Hills, 1961 [3];

Mrs. Philip D. Sang (née Elsie Olin, 1906–97), Chicago, by May 15, 1984;

Purchased at her sale, Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture, Sotheby-Parke-Bernet, New York, May 15, 1984, lot 14, as Grande Arabesque, Third Time, by Peggy Joan Amster (née Preuss, b. 1946), Tenafly, NJ, 1984–May 7, 1991;

Purchased at her sale, Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture, Part I, Sotheby’s, New York, May 7, 1991, lot 1, through Susan L. Brody and Associates, Inc., New York, by Marion (née Helzberg, 1931–2013) and Henry (1922–2019) Bloch, Shawnee Mission, KS, 1991–June 15, 2015;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 2015.

Notes

[1] Russian-Jewish sculptor Max Kaganovitch (1891–1978) opened a gallery in Paris in 1935. Due to his Jewish heritage, during World War II he was stripped of his French citizenship and forced to cede his business to Charles-Auguste Girard (1884–1968). He and his family went into exile, returning to France after the war. Kaganovitch took legal action to reclaim control of his gallery and officially reopened in 1949. He probably acquired Grande Arabesque, Third Time during this post-war period because he was actively buying, selling, and exhibiting Degas’s bronzes during the 1950s. Kaganovitch lent thirty-seven Degas bronzes—probably including the Nelson-Atkins sculpture—to the retrospective Edgar Degas (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, February 8–March 24, 1952) and twenty-five Degas bronzes to Edgar Degas: The Sculpture (Galerie Chalette, New York, October 3–29, 1955). Unfortunately, Kaganovitch’s stock books have not survived, although the Musée d’Orsay possesses some of his letters, press clippings, and exhibition photographs; see Fonds Kaganovitch, ODO 2007-3. None of these archival materials mention the Nelson-Atkins sculpture.

[2] The Juvilers probably purchased Grande Arabesque, Third Time from Kaganovitch because the catalogue from their collection sale says, “From the Galerie Max Kaganovitch, Paris” in the provenance for lot 9, suggesting a direct transfer. See Notable Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture: Bonnard, Braque, Buffet, Cézanne, Chagall, Degas, Dufy, Maillol, Matisse, Moore, Picasso, Renoir, Rouault, Soutine, Utrillo, and Vuillard; From the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Adolphe A. Juviler, New York, and Palm Beach, Sold by Their Order (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, October 25, 1961), 5. The couple’s son, Michael Juviler (1936–2017), confirmed that his parents sometimes purchased artwork in France. He did not possess any records pertaining to their acquisitions, however. See email from Michael Juviler to MacKenzie Mallon, NAMA, May 22, 2015, NAMA curatorial files.

[3] For the purchaser, see email from Lucy Economakis, Sotheby’s, to Brigid M. Boyle, NAMA, September 18, 2023, NAMA curatorial files. Edgardo Acosta Gallery was owned and operated by husband-and-wife dealers Francesca (née Hunter, 1914–2005) and Edgardo (1913–99) Acosta. It opened in 1957 and closed in 1979. The gallery’s ledgers are presumed lost. Letters to Acosta family descendants went unanswered.

Related Works

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

WAX MODEL

Edgar Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée), modeled 1885–90, wax statue on wooden base, without base: 18 5/16 x 10 1/16 x 20 3/4 in. (46.5 x 25.5 x 52.7 cm); with base: 20 1/16 x 17 3/8 x 20 3/4 in. (51 x 44.1 x 52.7 cm), Musée d’Orsay, Paris, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon, 1956, RF 2769.

MASTER CAST

60 / MODÈLE: Edgar Degas (artist), A.-A. Hébrard et Cie (foundry), Albino Palazzolo (founder), Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée), modeled 1885–90, cast 1919–21, copper alloy, base: 10 7/16 x 6 11/16 in. (26.5 x 17 cm); figure: 17 7/16 x 22 13/16 x 9 5/16 in. (44.3 x 57.9 x 23.7 cm), Norton Simon Art Foundation, Pasadena, M.1977.02.06.S.

SERIALIZED CASTS

60 / A: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, H.O. Havemeyer Collection, Bequest of Mrs. H.O. Havemeyer, 1929, 29.100.390.

60 / B: Private collection, Los Angeles, cited in Sara Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 547.

60 / C: Private collection, illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (New York: Sotheby’s, May 7, 2008), 28.

60 / D: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Mr. and Mrs. George Gard De Sylva Collection (M.46.8.7).

60 / E: Private collection, illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (New York: Christie’s, November 5, 2013), 62.

60 / F: The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham, Purchased 1942 (No. 42.1).

60 / G: Whereabouts unknown; formerly with Alfred Flechtheim (1878–1937) in 1927 until about 1934 when his collection was aryanized.

60 / H: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, Sweden, Gift 1948 Nationalmusei Vänner and major Alf Amundson, NMSk 1571.

60 / I: Private collection, United States of America, cited in Sara Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 547.

60 / J: Private collection, illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Art, Part I (New York: Sotheby’s, May 13, 1997), unpaginated.

60 / K: Denver Art Museum, Edward and Tullah Hanley Memorial Gift to the people of Denver and the area, 1974.354.

60 / L: Private collection, illustrated in Impressionist and Modern Art Evening Sale (London: Christie’s, February 2, 2004), 16-17.

60 / N: Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, purchase 1952, 51.72.

60 / O: Private collection, United Kingdom, on loan to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, England.

60 / P: Musée d’Orsay, Paris, RF 2072.

60 / Q: Whereabouts unknown, cited in Degas, exh. cat. (Bern: Kunstmuseum, 1951), unpaginated.

60 / R: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, Denmark, inv. nr. MIN 2670.

60 / S: Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Brazil, Doação Alberto José Alves, Alberto Alves Filho e Aníbal e Alcino Ribeiro de Lima, 1954, MASP.00360.

60 / T: Private collection, cited in Sara Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 547.

60 / unlettered: Národní galerie Praha, Prague, Czech Republic, P 1428.

60 / HER: Whereabouts unknown.

60 / HER.D: Whereabouts unknown.

60 / AP: Whereabouts unknown.

Exhibitions

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

Probably Edgar Degas, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, February 8–March 24, 1952, no. 140, as Danseres, naar rechtervoet kijkend.

Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, June 9–September 9, 2007, no. 15, as Grande Arabesque, Third Time (Grande arabesque, troisième temps).

Painters and Paper: Bloch Works on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, February 20, 2017–March 11, 2018, no cat.

From Farm to Table: Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Masterworks on Paper, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 16, 2018–March 24, 2019, no cat.

Women in Paris, 1850–1900, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, March 28, 2019–October 5, 2020, no cat.

Encore Degas! Ballet, Movement, and Fashion, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, November 20, 2021–November 21, 2022, no cat.

Crowning Glory: Millinery in Paris, 1880–1905, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 10, 2022–December 3, 2023, no cat.

References

Citation

Chicago:

Brigid M. Boyle, “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation in French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

MLA:

Boyle, Brigid M. “Degas, Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée),” documentation. French Paintings and Pastels, 1600–1945: The Collections of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/78973.5.902.4033.

John Rewald, ed., Degas: Works in Sculpture; A Complete Catalogue, trans. John Coleman and Noel Moulton (New York: Pantheon Books, 1944), no. XXXIX, pp. 24, 30–31, 94, illustration of another cast, as Grande Arabesque, Third Time and Grande Arabesque, troisième temps.

Probably Edgar Degas, exh. cat. (Amsterdam: Stedelijk Museum, 1952), unpaginated, as Danseres, naar rechtervoet kijkend.

John Rewald, Degas Sculpture: The Complete Works, trans. John Coleman and Noel Moulton (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1956), no. 39, pp. 83, 149, 151, 164–65, illustration of another cast, as Grande Arabesque, Third Time.

Notable Modern Paintings, Drawings, and Sculpture: Bonnard, Braque, Buffet, Cézanne, Chagall, Degas, Dufy, Maillol, Matisse, Moore, Picasso, Renoir, Rouault, Soutine, Utrillo, and Vuillard; From the Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Adolphe A. Juviler, New York, and Palm Beach, Sold by Their Order (New York: Parke-Bernet Galleries, October 25, 1961), 5, (repro.), as Grande Arabesque, Third Time.

Michèle Beaulieu, “Les sculptures de Degas: Essai de chronologie,” La Revue du Louvre et des musées de France 19, no. 6 (1969): 374, 374n39.

Franco Russoli and Fiorella Minervino, L’Opera completa di Degas (Milan: Rizzoli, 1970), no. S8, p. 140, illustration of another cast, as Terzo tempo della “Grande Arabesque.”

Charles Millard, The Sculpture of Edgar Degas (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976), 24, 35, 106, illustration of the wax model, as Grand Arabesque, Third Time.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings and Sculpture (New York: Sotheby’s, May 15, 1984), unpaginated, (repro.), as Grande Arabesque, troisième temps.

Jean-René Gaborit and Jack Ligot, eds., Sculptures en cire de l’ancienne Egypte à l’art abstrait (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1987), 70, 226, 229–32, 460, illustration of the wax model, as Danseuse: Grande Arabesque, 3^e^ temps, première étude.

Jean Sotherland Boggs, ed., Degas, exh. cat. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988), 586–87, illustration of the wax model and another cast, as First Arabesque Penchée.

John Rewald, Degas’s Complete Sculpture: Catalogue Raisonné, rev. ed. (San Francisco: Alan Wofsy Fine Arts, 1990), no. 39, pp. 116–17, 188–89, 201, 207, illustration of another cast, as Grande Arabesque, Third Time and Grande Arabesque, troisième temps.

Impressionist and Modern Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture, Part I (New York: Sotheby’s, May 7, 1991), unpaginated, (repro.), as Grande Arabesque, troisième temps.

Sara Campbell, “A Catalogue of Degas’ Bronzes,” Apollo 142, no. 402 (August 1995): 40, illustration of another cast, as Grand arabesque, third time.

Anne Pingeot, Degas: Sculptures (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1991), 74–75, 156, 194, illustration of another cast, as Danseuse, grande arabesque, troisième temps.

Joseph S. Czestochowski and Anne Pingeot, Degas Sculptures: Catalogue Raisonné of the Bronzes, exh. cat. (Memphis: International Arts, 2002), no. 60, pp. 238–39, 285–86, illustration of another cast, as Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque, Penchée).

Rebecca Dimling Cochran and Bobbie Leigh, “100 Top Collectors who have made a difference,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 3 (March 2006): 90.

Bobbie Leigh, “Magnificent Obsession,” Art and Antiques 28, no. 6 (June 2006): 65, as Grand Arabesque, third time.

Alice Thorson, “A ‘Final Countdown,’” Kansas City Star 126, no. 285 (June 29, 2006): B1.

“Inaugural Exhibitions Celebrate Kansas City,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2006): 3.

Alice Thorson, “A Tiny Renoir Began Impressive Obsession,” Kansas City Star 127, no. 269 (June 3, 2007): E4.

“Lasting Impressions: A Tribute to Marion and Henry Bloch,” Member Magazine (The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) (Fall 2007): 12.

Steve Paul, “Pretty Pictures: Marion and Henry Bloch’s collection of superb Impressionist masters,” Panache 4, no. 3 (Fall 2007): 20.

Richard R. Brettell and Joachim Pissarro. Manet to Matisse: Impressionist Masters from the Marion and Henry Bloch Collection, exh. cat. (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2007), 12, 15, 86–89, 158, (repro.), Grande Arabesque, Third Time (Grande arabesque, troisième temps).

Sara Campbell et al., Degas in the Norton Simon Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009), 365–68, 495, 497, 499, 547, illustration of the wax model, as Grande arabesque, third time (First arabesque penchée).

“A 75th Anniversary Celebrated with Gifts of 400 Works of Art,” Art Tattler International (February 2010): http://arttattl.ipower.com/archivemagnificentgifts.html.

Alice Thorson, “Blochs add to Nelson treasures,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 141 (February 5, 2010): A1, A8.

Carol Vogel, “O! Say, You Can Bid on a Johns,” New York Times 159, no. 54,942 (February 5, 2010): C26.

Alice Thorson, “Gift will leave lasting impression,” Kansas City Star 130, no. 143 (February 7, 2010): G1–G2.

Thomas M. Bloch, Many Happy Returns: The Story of Henry Bloch, America’s Tax Man (Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2011), 174–75.

Diane Stafford, “Bloch Gift to Go for Nelson Upgrade,” Kansas City Star 135, no. 203 (April 8, 2015): A8.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Officially Accessions Bloch Impressionist Masterpieces,” Artdaily.org (July 25, 2015): http://artdaily.com/news/80246/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-officially-accessions-Bloch-Impressionist-masterpieces, as Grand Arabesque, Third Time.

Julie Paulais, “Le Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art reçoit des tableaux impressionnistes en échange de leurs répliques,” Le Journal des arts (July 30, 2015): https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/patrimoine/le-nelson-atkins-museum-art-recoit-des-tableaux-impressionnistes-en-echange-de-leurs.

Josh Niland, “The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art Acquires a Renowned Collection of Impressionist and Postimpressionist Art,” architecturaldigest.com (July 31, 2015): https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/nelson-atkins-museum-accessions-bloch-art-collection.

Nancy Staab, “Van Gogh is a Go!” 435: Kansas City’s Magazine (September 2015): 76, as Grand Arabesque, Third Time.

“Nelson-Atkins to unveil renovated Bloch Galleries of European Art in winter 2017,” Artdaily.org (July 20, 2016): http://artdaily.com/news/88852/Nelson-Atkins-to-unveil-renovated-Bloch-Galleries-of-European-Art-in-winter-2017.

“Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art celebrates generosity of Henry Bloch with new acquisition,” Artdaily.org (October 18, 2016): https://artdaily.cc/news/90923/Nelson-Atkins-Museum-of-Art-celebrates-generosity-of-Henry-Bloch-with-new-acquisition#.XnKATqhKiUk.

Catherine Futter et al., Bloch Galleries: Highlights from the Collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2016), 83, (repro.), as Grande Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée).

Kelly Crow, “Museum Rewards Donor with Fake Art to Hang at Home,” Wall Street Journal (January 25, 2017): https://www.wsj.com/articles/museum-rewards-donor-with-fake-art-to-hang-at-home-1485370768.

David Frese, “Bloch savors paintings in redone galleries,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 161 (February 25, 2017): 1A.

Albert Hecht, “Henry Bloch’s Masterpieces Collection to Go On Display at Nelson-Atkins Museum,” Jewish Business News (February 26, 2017): http://jewishbusinessnews.com/2017/02/26/henry-bloch-masterpieces-collection/.

David Frese, “Inside the Bloch Galleries: An interactive experience,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 169 (March 5, 2017): 5D, (repro.), as Grand Arabesque, Third Time (First Arabesque Penchée).

“Editorial: Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star (March 7, 2017), http://www.kansascity.com/opinion/editorials/article 137040948.html [repr., in “Thank you, Henry and Marion Bloch,” Kansas City Star 137, no. 172 (March 8, 2017): 16A].

Hampton Stevens, “(Not Actually) 12 Things To Do During The Big 12 Tournament,” Flatland: KCPT’s Digital Magazine (March 9, 2017): http://www.flatlandkc.org/arts-culture/sports/not-actually-12-big-12-tournament/

Laura Spencer, “The Nelson-Atkins’ Bloch Galleries Feature Old Masterworks and New Technology,” KCUR (March 10, 2017): http://kcur.org/post/nelson-atkins-bloch-galleries-feature-old-masterworks-and-new-technology#stream/0

Victoria Stapley-Brown, “Nelson-Atkins Museum’s new European art galleries come with a ‘love story,’” Art Newspaper (March 10, 2017):

Harry Bellet, “Don du ciel pour le Musée Nelson-Atkins,” Le Monde (March 13, 2017): http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2017/03/13/don-du-ciel-pour-le-musee-nelson-atkins_5093543_1655012.html.

Menachem Wecker, “Jewish Philanthropist Establishes Kansas City as Cultural Mecca,” The Forward (March 14, 2017): http://forward.com/culture/365264/jewish-philanthropist-establishes-kansas-city-as-cultural-mecca/ [repr., in Menachem Wecker, “Kansas City Collection Is A Chip Off the Old Bloch,” Forward (March 17, 2017): 20-22].

Juliet Helmke, “The Bloch Collection Takes up Residence in Kansas City’s Nelson Atkins Museum,” Blouin ArtInfo International (March 15, 2017): http://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/2005267/the-bloch-collection-takes-up-residence-in-kansas-citys.

Louise Nicholson, “How Kansas City got its magnificent museum,” Apollo: The International Art Magazine (April 7, 2017): https://www.apollo-magazine.com/how-kansas-city-got-its-magnificent-museum/

Lilly Wei, “Julián Zugazagoitia: ‘Museums should generate interest and open a door that leads to further learning,’” Studio International (August 21, 2017): http://studiointernational.com/index.php/julian-zugazagoitia-director-nelson-atkins-museum-of-art-kansas-city-interview.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry Bloch, H&R Block’s cofounder, dies at 96,” Boston Globe (April 23, 2019): https://www3.bostonglobe.com/metro/obituaries/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-block-cofounder/?arc404=true.

Megan McDonough, “Henry Bloch, whose H&R Block became world’s largest tax-services provider, dies at 96,” Washington Post (April 23, 2019): https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/henry-bloch-whose-handr-block-became-worlds-largest-tax-services-provider-dies-at-96/2019/04/23/19e95a90-65f8-11e9-a1b6-b29b90efa879_story.html.

Claire Selvin, “Henry Wollman Bloch, Collector and Prominent Benefactor of Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Is Dead at 96,” ArtNews (April 23, 2019): http://www.artnews.com/2019/04/23/henry-bloch-dead-96/.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “Henry Bloch, co-founder of H&R Block, dies at 96,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 219 (April 24, 2019): 1A.

“Henry Wollman Bloch (1922–2019),” Artforum (April 24, 2019): https://www.artforum.com/news/henry-wollman-bloch-1922-2019-79547.

Robert D. Hershey Jr., “Henry W. Bloch, Tax-Preparation Pioneer (and Pitchman), Is Dead at 96,” New York Times 168, no. 58,307 (April 24, 2019): A20.

Frank Morris, “Henry Bloch, Co-Founder Of H&R Block, Dies At 96,” NPR (April 24, 2019): https://www.npr.org/2019/04/24/716641448/henry-bloch-co-founder-of-h-r-block-dies-at-96.

Ignacio Villarreal, “Nelson-Atkins mourns loss of Henry Bloch,” ArtDaily.org (April 24, 2019): http://artdaily.com/news/113035/Nelson-Atkins-mourns-loss-of-Henry-Bloch#.XMB76qR7laQ.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “H&R Block co-founder, philanthropist Bloch dies,” Cass County Democrat Missourian 140, no. 29 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Eric Adler and Joyce Smith, “KC businessman and philanthropist Henry Bloch dies,” Lee’s Summit Journal 132, no. 79 (April 26, 2019): 1A.

Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 225 (April 30, 2019): 4A [repr., in Luke Nozicka, “Family and friends remember Henry Bloch of H&R Block,” Kansas City Star 139, no. 228 (May 3, 2019): 3A].

Eric Adler, “Sold for $3.25 million, Bloch’s home in Mission Hills may be torn down,” Kansas City Star 141, no. 90 (December 16, 2020): 2A.

Kristie C. Wolferman, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2020), 345.