Visitors Will Discover Ancient Egyptian Works of Art from Royal Tombs to Daily Life

Kansas City, MO, September 23, 2019 – Queen Nefertari, the beloved Great Royal Wife of the Pharaoh Ramesses II, will be celebrated in the exhibition Queen Nefertari: Eternal Egypt, on view at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art from November 15, 2019 to March 29, 2020. Drawn from the Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy, the exhibition will bring together 230 works of art that present the richness of life in ancient Egypt from more than 3,000 years ago, focusing on the role of women – goddesses, queens, and artisans.

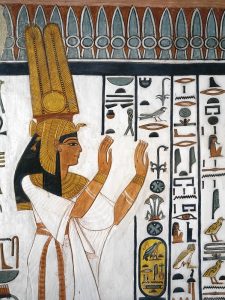

Although mysterious to us today, Queen Nefertari was the favorite wife and even diplomatic helpmate to Ramesses II, who called her “The One for Whom the Sun Shines.” A colossal temple was built in her honor at Abu Simbel, and her tomb in the Valley of the Queens is known for its vivid artistry. Sometimes called “the Sistine Chapel of Egypt,” the tomb’s elaborately painted walls feature gods and winged goddesses, animals, insects, and hieroglyphs, illustrating the intricate process of passing through the underworld to eternal life.

Visitors to the exhibition will view several personal objects from her tomb, plus an array of objects from royal and day-to-day life in Egypt during the 19th Dynasty of the New Kingdom — majestic sculptures, intricately painted sarcophagi, jewelry, and perfume and cosmetics jars. Visitors also will discover the village Deir el-Medina, where artisans lived and worked, creating elaborate tombs and necessary materials for the afterlife.

“It will be thrilling to have these ancient works of art in our midst, to imagine the hands that created them and the importance these objects played in Egyptian culture,” said Julián Zugazagoitia, Menefee D. and Mary Louise Blackwell Director & CEO of the Nelson-Atkins. “W hat a privilege to welcome objects from one of the most significant archaeological sites in Egypt – the Valley of the Queens.”

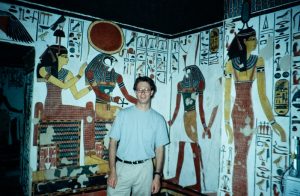

Zugazagoitia holds an enduring connection with Queen Nefertari. As a young man, he was in Egypt in the 1990s, consulting on behalf of the Getty Conservation Institute to determine how best to preserve Nefertari’s tomb in the midst of increasing tourism. He also curated the exhibition Nefertari: Light of Egypt, which opened in 1994 in Rome, then traveled to Venice and Turin.

The current exhibition Queen Nefertari: Eternal Egypt is drawn from the world-renowned Museo Egizio in Turin, Italy, which holds some 40,000 objects from all periods of Egyptian history.

Discovering Nefertari’s Tomb

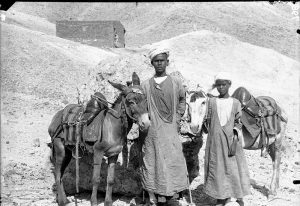

Queen Nefertari’s tomb was discovered in 1904 during the Italian expedition led by Ernesto Schiaparelli, then the director of Museo Egizio, who gained vast access and excavation permits in the Valley of the Queens, on the West Bank of the ancient capital of Thebes. At the time, his collaborator described the area as an “isolated valley, seldom crossed by the traveler, the undisturbed reign of hawks, wolves, and jackals, with no trace of vegetation and yet solemn in its sad silence.” Archival photographs from that time show not only the sweeping landscape but also the faces of many laborers, of all ages, who worked on the excavations.

Members of the excavation crew essentially removed the top layer of arid soil – flint and limestone chips – to reveal hidden entries to underground chambers. They discovered dozens of tombs and shafts, including Nefertari’s magnificent burial chamber. Robbers had already looted the tomb, much like other tombs that were plundered probably during ancient times.

Members of the excavation crew essentially removed the top layer of arid soil – flint and limestone chips – to reveal hidden entries to underground chambers. They discovered dozens of tombs and shafts, including Nefertari’s magnificent burial chamber. Robbers had already looted the tomb, much like other tombs that were plundered probably during ancient times.

At the time of the discovery, Schiaparelli wrote: “Although the grave goods found were very few, (we) nevertheless rejoiced in the discovery, since apart from being the tomb of one of the most famous Egyptian queens, it was also of a singular beauty.”

Objects found inside the tomb, presumed to belong to Queen Nefertari, will be part of the exhibition: fragments of pink granite that formed the lid to her sarcophagus, 34 wooden shabtis (small figures who could perform manual labor in the afterlife), and a beautiful amulet of gold-painted wood and blue faience (a clay-like material), in the shape of a djed-pillar, suggested stability and eternal life for the deceased. Visitors also will see a pair of mummified knees that may be the queen’s only surviving mortal remains, and a pair of simple fiber sandals (women’s size 9) that might have belonged to and been used by the queen.

Nefertari’s tomb was constructed around 1250 B.C.E., at the height of New Kingdom craftsmanship. It consists of two parts – the upper antechambers and the lower burial chamber, connected by descending staircases. The structure evoked a convoluted path that the deceased had to follow to reach the afterlife. A wooden model of the tomb, complete with paintings to scale, was built following discovery of the tomb, and that historic model will be part of the exhibition. It was considered such an accurate model that it helped scientists of the Getty Conservation Institute in restoring the tomb.

Royal Life During the 19th Dynasty

The New Kingdom of Egypt, about a thousand years after the era of the great pyramids of Giza, and about 200 years after the famous Queen Nefertiti lived, was a golden age of civilization, from the 18th to 20th dynasties, or 1539 to 1076 B.C.E. Wealth flowed into the land of the Nile, and important resources such as gold, silver, and precious stones were available.

Queen Nefertari: Eternal Egypt will cast light on royal life in palaces, the everyday life of artisans, and the roles of women in Egyptian society. The exhibition also will highlight the powerful belief system and ritual practices around death and the afterlife.

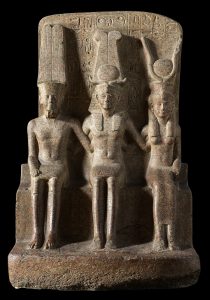

Visitors will see palace decoration, statues, and relief sculptures. Among the major works of art are the monumental granite sculpture of Ramesses II (one of the most well-known pharaohs, with a 66-year reign from ca. 1279 to 1213 B.C.E.), seated between Amun, the sun god, and Amun’s wife Mut. On view will be the grand Statue of Thutmose I from the Temple of Amun, and four large statues of Sekhmet, “the powerful one,” a fierce goddess of divine wrath who needed to be appeased every day.

On a more intimate scale, visitors will see musical instruments, bronze mirrors, boxes and jars for cosmetic powders and ointments, earrings, and necklaces. The exhibition also will feature a kohl tube, which would have held the black eyeliner that emphasized a person’s beauty and protected the eyes from bacterial infections.

“We are fortunate to be able to see this ancient society clearly through the works of art that are still so powerful today,” said Catherine L. Futter, Director of Curatorial Affairs at the Nelson-Atkins. “This was a time of hierarchy, order, and defined roles, and yet the unifying element is artistry and appreciation for beauty, from the granite statues of pharaohs to the intricate carvings on a wooden comb.”

Visitors to the exhibition also will see a story of murder, as told on fragmented papyrus. Known as the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, or the Harem Conspiracy Papyrus, the story was written in hieratic – a simplified, cursive hieroglyph form. In the 32nd year of his reign, Pharaoh Ramesses III was murdered in an attempted coup that involved one of his wives, her son, and others who were part of the royal women’s palace. The conspirators were captured and put on trial, and the court proceedings were chronicled on this papyrus scroll. Some of the accused were reprimanded, while others were executed or forced to commit suicide.

Living and Working in Deir el-Medina

Ancient Thebes was composed of mud-brick homes, and, as a result, few ancient Egyptian domestic sites still exist today. The village of Deir el-Medina is an exception. The ruins sit within walking distance to the Valley of the Kings to the north, funerary temples to the east, and the Valley of the Queens to the west.

Deir el-Medina was home to the distinguished artisans who worked on royal tombs and temples, including masons, draftsmen, painters, as well as scribes, administrators, and service workers. Household items, preserved tools, and sacred objects provide a glimpse into the way people lived, worked, and practiced religion more than 3,000 years ago.

“When we think of ancient Egypt, we often think of pharaohs and other royal figures,” said Anne Manning, Director of Education and Interpretation. “However, this exhibition offers a broader view of this vibrant civilization by presenting the artistic achievements and experiences of non-royal Egyptians.”

The exhibition will feature tools such as brushes and draftsmen’s sticks, pickaxes and chisels, ostraca (limestone or pottery fragments with inscriptions or drawings), fragments from a papyrus work journal, and statues. A paintbrush in the exhibition is still coated in Egyptian blue pigment.

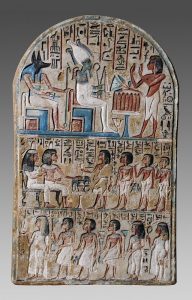

Visitors to Queen Nefertari: Eternal Egypt will see a number of vivid stele, some stone and some wood. They were carved, painted, or both, often representing a deceased person’s life. One exceptional example is the funerary stela of the craftsman Nakhi, with hieroglyphs and god and human figures. Nakhi is depicted making offerings to the two main deities of the afterlife, Osiris and Anubis. Nakhi and his wife also are shown receiving an offering from their son, robed in a panther skin, indicating that he is a priest.

After Nefertari

In the final section of the exhibition, visitors will view a number of coffins from the Late Period, 25th to 26th dynasties. These coffins took on a human form, and the features of the deceased were sculpted or painted with eyes shown open, as if the deceased were still alive.

While excavating in the Valley of the Queens, Ernesto Schiaparelli and his colleagues discovered the tombs of Khaemwaset and Setherkhepeshef, two sons of Ramesses III. Their tombs were constructed during the 20th dynasty, but later reused during the 24th and 25th dynasties. Dozens of coffins were piled inside the tombs, many belonging to the families of two temple priests.

Queen Nefertari: Eternal Egypt will feature not only original objects from Egypt, but also reproductions of the paintings on Nefertari’s tomb wall. Also, videos created by the gaming company Ubisoft will offer a simulation of everyday life in Egypt.

“I know Kansas City will be transported into ancient Egyptian culture and beauty,” Zugazagoitia said. “These works of art will evoke a fascination with the mystery of rituals and beliefs, and they will ignite further interest in archaeology and the search for meaning in other cultures.”

The exhibition was organized by Museo Egizio, Turin, and StArt in collaboration with The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art and Pointe-à-Callière, Montréal Archaeology and History Complex, and National Geographic Society.

In Kansas City, the exhibition is supported by Paul DeBruce and Linda Woodsmall-DeBruce; Shirley Bush Helzberg; G. Kenneth and Ann Baum; Ronald and Nancy Jones; Jill and Don Hall, Jr.; Marion and Henry Bloch Family Foundation; Imperial PFS; Neil D. Karbank; Estelle S. and Robert A. Long Ellis Foundation; The Barton P. and Mary D. Cohen Charitable Trust; JE Dunn Construction Company; Nancy and Rick Green; Liz and Greg Maday; Miller Nichols Charitable Foundation; and Thomas and Sally Wood Foundation.

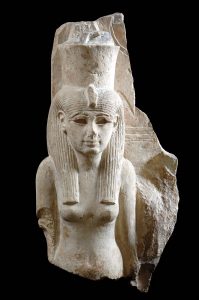

Image captions:

Statue of the goddess Mut, New Kingdom, 18th-20th Dynasties, 1539 – 1076 B.C.E. Limestone, 21 1/4 x 11 x 8 1/2 inches (54 x 28 x 22 cm). Museo Egizio, Turin.

Egypt, Thebes, Luxor, Valley of the Queens, Tomb of Nefertari, mural painting of Queen reciting mortuary formula in Burial chamber from 19th dynasty (detail) / De Agostini Picture Library / S. Vannini / Bridgeman Images.

Julián Zugazagoitia in Queen Nefertari’s tomb, 1993. Photo provided by Julián Zugazagoitia.

Archival photograph of Valley of the Queens. Photo provided by Museo Egizio.

Djed-pillar amulet, 1279-1213 B.C.E. Gilded wood, blue glass, 5 1/8 x 2 3/16 x 3/8 inches (13 x 5.5 x 1 cm). Museo Egizio, Turin.

Sandals, ca. 1279-1213 B.C.E. Vegetal Fibers (Palm leaves). Tomb of Nefertari, Valley off the Queens. New Kingdom, 19th dynasty, reign of Ramesses II (ca. 1279-1213 B.C.E.) Museo Egizio, Turin.

Statue of Ramesses II seated between the gods Amun and Mut, New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, 1279-1213 B.C.E. Granite, 67 x 44 1/2 x 37 inches (170 x 113.5 x 94 cm). Museo Egizio, Turin.

Stela of Nakhi, “servant in the Place of Truth,”offering to Osiris and Anubis, likely from Deir el-Medina, New Kingdom, 18th – 20th Dynasties, 1539-1076 B.C.E. Sandstone, 39 1/2 x 25 x 6 inches (100 x 63 x 15 cm). Museo Egizio, Turin.

Ankhpakhered’s sarcophagus, 746-655 B.C.E. Stuccoed and painted wood, 69 11/16 x 13 9/16 x 18 1/8 inches (177 x 34.5 x 46 cm). Museo Egizio, Turin.

Museo Egizio

The Museo Egizio, founded in Turin (Italy) in 1824, is the oldest museum dedicated to Egyptian antiquities and represents the second most important collection, outside of Egypt, of art and artifacts from this fascinating civilization that developed on the banks of the Nile. In its almost 200 years of history, the Museum has repeatedly been transformed, renewed and rethought, in an attempt to conjugate the needs of the scientific research with the ones of the visitors. The permanent exhibition presents the history of the museum and its collections, the archaeological contexts of the objects on display, as well as the stories behind the expeditions, their organization and their discoveries. The exhibition space consists of around 10,000 square meters and 15 rooms filled with 3,300 artifacts distributed on five floors, as well as a 600-square-meter area dedicated to temporary exhibitions.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

The Nelson-Atkins in Kansas City is recognized nationally and internationally as one of America’s finest art museums. The museum, which strives to be the place where the power of art engages the spirit of community, opens its doors free of charge to people of all backgrounds. The museum is an institution that both challenges and comforts, that both inspires and soothes, and it is a destination for inspiration, reflection and connecting with others.

The Nelson-Atkins serves the community by providing access to its renowned collection of more than 41,000 art objects and is best known for its Asian art, European and American paintings, photography, modern sculpture, and Native American and Egyptian galleries. Housing a major art research library and the Ford Learning Center, the Museum is a key educational resource for the region. In 2017, the Nelson-Atkins celebrates the 10-year anniversary of the Bloch Building, a critically acclaimed addition to the original 1933 Nelson-Atkins Building.

The Nelson-Atkins is located at 45th and Oak Streets, Kansas City, MO. Hours are Monday, Wednesday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m.; Thursday/Friday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m.; Sunday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Admission to the museum is free to everyone. For museum information, phone 816.751.1ART (1278) or visit nelson-atkins.org.

For media interested in receiving further information, please contact:

Kathleen Leighton, Manager, Media Relations and Video Production

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

816.751.1321

kleighton@nelson-atkins.org