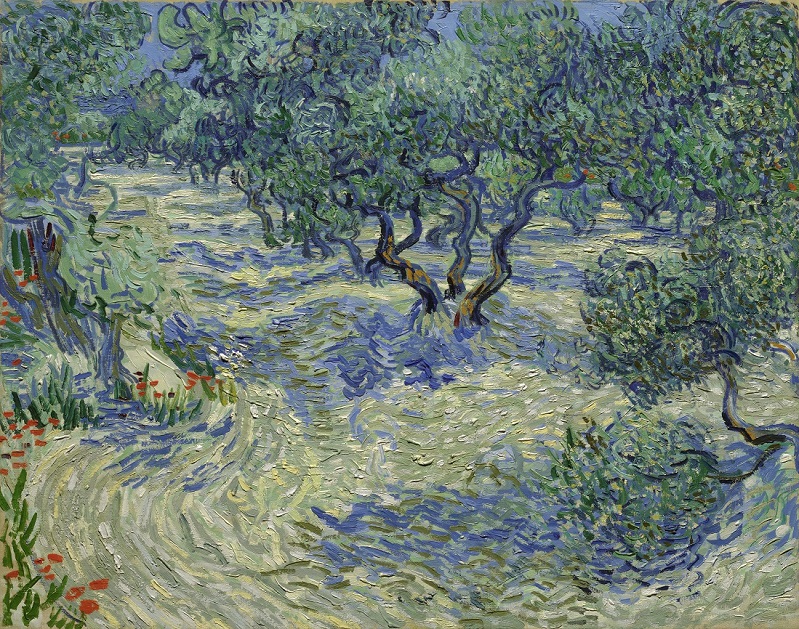

Insect Links Painting to Travails of the Artist

Kansas City, MO Nov. 6, 2017 – A small grasshopper embedded for more than a century in the thick paint of Vincent van Gogh’s Olive Trees was discovered as part of research for a catalogue of the French painting collection at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City. The discovery is just one of the exciting results that emerged as scientific study and art historical research were combined at the museum to better understand the artist’s process.

“Olive Trees is a beloved painting at the Nelson-Atkins, and this scientific study only adds to our understanding of its richness,” said Julián Zugazagoitia, Menefee D. and Mary Louise Blackwell CEO & Director of the Nelson-Atkins. “Van Gogh worked outside in the elements, and we know that he, like other plein air artists, dealt with wind and dust, grass and trees, and flies and grasshoppers.”

The new findings are part of work by skilled curators, conservators and outside scientists who are adding to the scholarship on 104 French paintings and pastels at the Nelson-Atkins. The resulting online catalogue will be published in installments beginning in 2019 and will be a definitive resource that offers extended entries for core works, including Olive Trees.

While examining the painting under magnification, Paintings Conservator Mary Schafer discovered the tiny grasshopper embedded in the paint. The insect was found in the lower foreground of the landscape, but cannot be seen by visitors through casual observation. “It is not unusual to find insects or plant material in a painting that was completed outdoors,” Schafer said. “But in this case, we were curious if the grasshopper could be used to identify the particular season in which this work was painted.”

The team contacted paleo-entomologist Dr. Michael S. Engel, Senior Curator and Professor, University of Kansas and Associate, American Museum of Natural History in New York, for further study. Engel observed that the thorax and abdomen of the grasshopper were missing and that no sign of movement was evident in the surrounding paint, indicating that the insect was dead before landing on van Gogh’s canvas. The grasshopper could not be used for more precise dating of the painting.

Van Gogh described his outdoor painting practice and the challenges in an 1885 letter to his brother, Theo: “But just go and sit outdoors, painting on the spot itself! Then all sorts of things like the following happen – I must have picked up a good hundred flies and more off the 4 canvases that you’ll be getting, not to mention dust and sand…when one carries them across the heath and through hedgerows for a few hours, the odd branch or two scrapes across them…”

While the grasshopper becomes an engaging topic for museum visitors, more significant research on Olive Trees is underway. Analysis by Mellon Science Advisor John Twilley confirms that van Gogh used a type of red pigment that gradually faded over time. These findings suggest that areas where van Gogh employed this red, either alone or mixed with other colors, appear slightly different today than when the painting was completed.

“Color relationships were central to van Gogh’s practice,” said Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Louis L. and Adelaide C. Ward Senior Curator of European Art. “Since we now know that portions of the canvas where van Gogh employed this particular red pigment have faded, those color relationships are altered.”

The artist’s letters often referred to his works by their dominant colors, which means the more recent changes in appearance can present uncertainty as to which painting van Gogh alluded to in his descriptions. With funding through the museum’s Andrew W. Mellon Endowment for Scientific Research in Conservation, more research is being conducted to evaluate the impact of these color shifts. The research is expected to clarify the original appearance of Olive Trees and to offer a clearer understanding of its place within van Gogh’s series of works on this theme.

Vincent van Gogh (Dutch, 1853 – 1890). Olive Trees.1889. Oil on canvas. Dimensions: Unframed: 28 3/4 x 36 1/4 inches (73.03 x 92.08 cm). Framed: 37 3/4 x 45 1/2 x 2 inches (95.89 x 115.57 x 5.08 cm). Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust. 32-2.

Photomicrograph, Olive Trees, 32-2. This image, taken through a microscope, captures the grasshopper embedded in the paint of Olive Trees.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

The Nelson-Atkins in Kansas City is recognized nationally and internationally as one of America’s finest art museums. The museum, which strives to be the place where the power of art engages the spirit of community, opens its doors free of charge to people of all backgrounds. The museum is an institution that both challenges and comforts, that both inspires and soothes, and it is a destination for inspiration, reflection and connecting with others.

The Nelson-Atkins serves the community by providing access to its renowned collection of nearly 40,000 art objects and is best known for its Asian art, European and American paintings, photography, modern sculpture, and new American Indian and Egyptian galleries. Housing a major art research library and the Ford Learning Center, the Museum is a key educational resource for the region. In 2017, the Nelson-Atkins celebrates the 10-year anniversary of the Bloch Building, a critically acclaimed addition to the original 1933 Nelson-Atkins Building.

The Nelson-Atkins is located at 45th and Oak Streets, Kansas City, MO. Hours are Wednesday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m.; Thursday/Friday, 10 a.m.–9 p.m.; Saturday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m.; Sunday, 10 a.m.–5 p.m. Admission to the museum is free to everyone. For museum information, phone 816.751.1ART (1278) or visit nelson-atkins.org.

For media interested in receiving further information, please contact:

Kathleen Leighton, Manager, Media Relations and Video Production

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

816.751.1321

kleighton@nelson-atkins.org