Nelson-Atkins Surveillance Exhibition Explores Sneaky Side of Photography

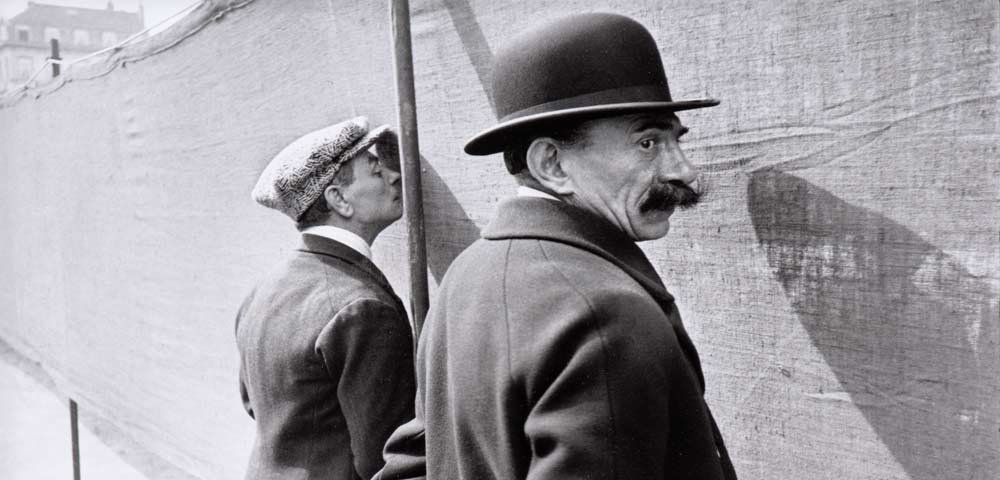

Kansas City, Mo., Sept. 23, 2016–Surveillance cameras in the 21st century are practically everywhere–on street corners, in shops, in public buildings, silently recording our every movement. Yet this is not a construct of modern times. As soon as cameras were introduced in the 1880s, anyone could be unknowingly photographed at any time. It was an unfortunate fact of life. The exhibition Surveillance opened at The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City September 16, examining the role of surreptitious photography from the mid-19th century to the present day.

“This body of work represents a sign of our times,” said Julián Zugazagoitia, Menefee D. and Mary Louise Blackwell CEO & Director of the Nelson-Atkins. “Cameras have been recording our movements, many times secretly, since photography began. But it was the tragedy of 9/11 that increased our awareness of this constant presence and brought a new and chilling meaning to the art, and the intention, of surveillance.”

“This body of work represents a sign of our times,” said Julián Zugazagoitia, Menefee D. and Mary Louise Blackwell CEO & Director of the Nelson-Atkins. “Cameras have been recording our movements, many times secretly, since photography began. But it was the tragedy of 9/11 that increased our awareness of this constant presence and brought a new and chilling meaning to the art, and the intention, of surveillance.”

Dating from 1864–2014, the works in Surveillance fall under these categories: spying or hidden cameras, photography of the forbidden, military surveillance, areas of heavy surveillance and mapping satellites and drones. There are also examples of counter-surveillance that either prevent watching or surveille the watchers.

“Twenty-first century technology—like Google Earth View and drone photography—have provided photographers with a treasure trove of surveillance images,” said Jane L. Aspinwall, Associate Curator, Photography. “This work provokes uneasy questions about who is looking at whom and the limits of artistic expression.”

Photographer Roger Schall, formerly a French news reporter, secretly recorded the Nazi occupation of Paris beginning in June 1940. His photographs document his daily routine and illustrate how completely the Nazis permeated every facet of Parisian life.

British photographer Mishka Henner, in his series Dutch Landscapes, uses Google satellite views of locations that have been censored by the Dutch government because of concerns about the visibility of political, economic and military locations. Many countries blur, pixilate or whiten sensitive sites. The Dutch method, however, employs bold, multi-colored polygons. The resulting photograph is an artistic, visual contrast between secret sites and the surrounding rural environment, providing an unsettling reflection on surveillance and the contemporary landscape.

Other photographers employ techniques to circumvent surveillance. Adam Harvey creates “looks” that block online facial recognition software. The contours of the face are manipulated in such a way that a computer is not able to identify a person, which can be a useful tool for social media sites like Facebook, in which users can search an entire archive for one particular face.

A series of critically acclaimed films will be shown in Atkins Auditorium in October in conjunction with this exhibition. Belgian photographer Tomas van Houtryve will discuss his work as it relates to contemporary warfare on Thursday, Oct. 6. For more information about programming, go to nelson-atkins.org/. Surveillance closes on Jan. 29, 2016.

Image caption: Mishka Henner, Belgian (b. 1976). Staphorst Ammunition Depot, 2011. Inkjet print, 31 1/4 × 35 1/8 inches. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Gift of the Hall Family Foundation, 2014.31.19.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

The Nelson-Atkins in Kansas City is recognized nationally and internationally as one of America’s finest art museums. The Nelson-Atkins serves the community by providing access and insight into its renowned collection of nearly 40,000 art objects and is best known for its Asian art, European and American paintings, photography, modern sculpture, and new American Indian and Egyptian galleries. Housing a major art research library and the Ford Learning Center, the Museum is a key educational resource for the region. The institution-wide transformation of the Nelson-Atkins has included the 165,000-square-foot Bloch Building expansion and renovation of the original 1933 Nelson-Atkins Building.