- Artists at Work

- Ready for Art

- Safe Haven

- Art: Patience to Create

- Art: Stories about Patience

- Slow Looking Challenge

PATIENCE AND ENDURANCE DURING DIFFICULT TIMES

Waiting is hard. We are told to stay home, and the sameness of the days wears on us. It requires patience. Some of us must go to work because we are essential, and the days are long. It requires endurance.

This week the Nelson-Atkins turns its attention to those two human qualities. For inspiration, we are looking back at what some people have done in the name of patience and endurance.

Artists at Work

George Anthony Morton

George Anthony Morton grew up in Kansas City in a difficult setting of drugs and street life and went to federal prison at age 20. During nine years in prison, he used that time as “a monastery and a university” and learned to paint like the masters, impressing everyone around him with his determination. When released, he enrolled in and graduated from the Florence Academy of Art, then founded a workshop and studio in Atlanta called Atelier South. He came to the Nelson-Atkins in 2019 to copy Rembrandt’s Young Man in a Black Beret.

Daniel MacMorris

Kansas City artist Daniel MacMorris won the contract in 1937 to paint the ceiling of Rozzelle Court. It was a pain-staking process of creating designs for each of the 64 ceiling bays, transferring the sketches, then painting directly onto the ceiling. The paintings, in muted colors, were meant to enhance the architecture and were based on Italian Renaissance designs.

The project was nearly complete in 1939, but the scaffolding had to be taken down for a garden party at the museum. More than 30 years later, in 1974, MacMorris returned to finish his work.

Ready for Art The 1933 Opening of The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art

The years-long process that led to opening The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in 1933 is a study in patience and endurance. From the founding bequests of Mary Atkins and William Rockhill Nelson in the early 1900s, to building the museum, its collection, and staff, to its opening during the depths of the Great Depression, trustees, advisors, and staff persevered in realizing the dream of bringing a world-class art museum to Kansas City. Established in difficult and challenging times, the new museum offered a respite from the pessimism of the era and embodied Kansas City’s cultural aspirations and can-do spirit.

Safe Haven The Nelson-Atkins and the Protection of Art During WWII

We can look back to World War II with an understanding of the endurance and sacrifice it required of all citizens. As nine million Americans fought overseas, those on the home front worked to help each other bear the long years of war. The Nelson-Atkins played a role, too, as a place of refuge for art works evacuated from museums and collections on the east and west coasts, as well as for the Kansas City public as they waited patiently for a return to normalcy.

Art: Patience to Create

The Lakota woman who made these moccasins depicting Double Woman collected, sorted, dyed, softened, and wove porcupine quills into a rawhide surface. The process took time and involved risk of injury. She also carefully strung and stitched glass beads and metal cones onto the moccasins, uniting the painstaking two methods of decoration. The image of Double Woman, the spiritual figure who inspired quillwork, might make the moccasins symbolize creativity itself.

Woman’s Moccasins, North American Indian, Lakota (Teton Sioux), North or South Dakota, ca. 1890. Rawhide, native leather, porcupine quills, glass beads, cotton cloth and metal cones. Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 33-1182/1,2

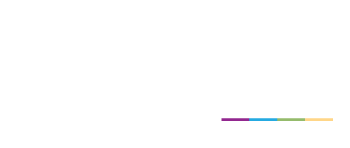

Parents often tell their children to “sit still.” That was especially true with early photography. This young girl had to hold her pose for up to a minute, and that was after the photographer had polished a silver-plated copper plate and treated it with iodine. The lengthy process resulted in an astonishingly accurate image, making the trouble worth it for eager clients.

Unknown. Girl in front of scenic backdrop, ca. 1844. Daguerreotype, plate (sixth): 3-1/4 x 2-3/4 inches. Gift of Hallmark Cards, Inc., 2005.27.4704

To make this miniature portrait, Anna Claypoole Peale worked with watercolor, a fragile paint, on ivory, a finicky base. The greasy surface repels water, making it difficult to work with. She also used a very small brush with only a few bristles, in a technique of dots (stipples) and cross-hatches to build forms. Thus, every finished portrait miniature is a record of determined effort.

Anna Claypoole Peale, American (1791–1878). Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1835. Watercolor on ivory, 2-3/4 x 2-1/4 inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John W. Starr and the Starr Foundation, Inc., F58-60/98

Art: Stories about Patience

In the midst of a storm at sea, Jesus sleeps calmly, while his disciples react in fear to the growing darkness and surging waves. This painting, Christ on the Sea of Galilee, depicts the stormy waters, but as we know from the New Testament story, Jesus will awaken and calm the waters. He will also ask his disciples, “Why are you afraid?” The French artist Eugène Delacroix came back to this theme many times, consistently portraying the serenity of Jesus against the uncertainty of the moment.

Eugène Delacroix, French (1798-1863). Christ on the Sea of Galilee, ca. 1841. Oil on canvas, 18 x 21 1/2 inches (45.7 x 54.6 cm). Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 89-16.

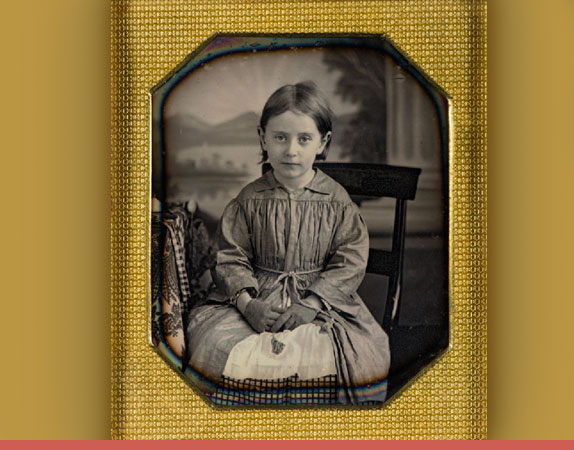

John Constable today is considered among the greatest 18th-century English landscape painters, but he did not achieve recognition or fame until nearly the end of his life. He suffered great hardships, including the loss of his beloved wife Maria, who died shortly after giving birth to their seventh child, leaving Constable alone to raise all of them. Constable first visited Helmingham Park in 1800 and created an oil sketch, but it was 20 years before he painted this large-scale canvas.

John Constable, English (1776-1837). The Dell at Helmingham Park, 1830. Oil on canvas, 44 5/8 x 51 1/2 inches (113.4 x 130.8 cm). Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust, 55-39.

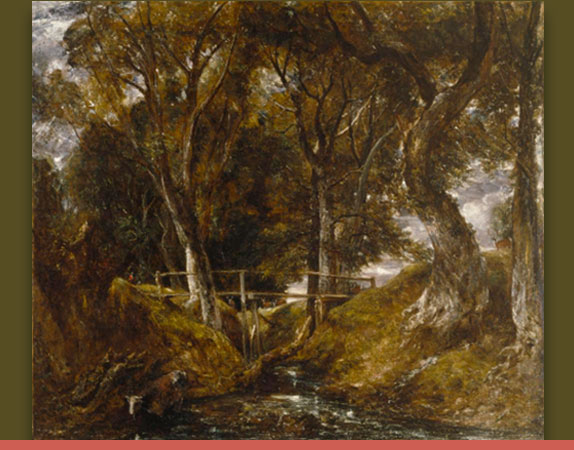

This poignant still life, one of a series of floral works, was painted within the last year and a half of Édouard Manét’s life when the artist was bedridden. At this time, Manét was visited by only his closest friends, who brought him fresh flowers that he painted from his bedside. The restraint and simplicity of these compositions highlight the artist’s masterful application of paint. White Lilacs in Crystal Vase was part of the private collection of Marion and Henry Bloch, now part of the Nelson-Atkins collection.

Edouard Manét, French (1832-1883).White Lilacs in a Crystal Vase, 1882 or 1883. Oil on canvas, 22 1/8 x 13 3/4 inches (56.2 x 34.9 cm). The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Gift of Henry W. and Marion H. Bloch, 2015.13.12.

Slow Looking Challenge

People around the world go to art museums to look at works of art. How much time do you think a person spends looking at one artwork in a museum? Take the Slow Looking Challenge and compare how much you see in art with a quick glance and how much you see when you spend more time looking.