How to Cite

To cite a specific biography on this page, add the author and artist details to the following citations:

Chicago:

Author First Name Last Name, “Artist Name (Artist nationality, life dates),” biography, in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.2.5000.

MLA:

Author Last Name, First Name. “Artist Name (Artist nationality, life dates),” biography. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/8322.2.5000.

A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W XYZ

A

B

James Barry (probably English, 1755–1835)

Work by This Artist

Mystery has long surrounded the miniaturist James Barry, including his first name, which was until recently believed to be John.1The confusion is likely due to Royal Academy exhibition records only ever referring to him as “J. Barry.” To further muddy the waters, there was another artist named James Barry (Irish, 1741–1806), an oil painter, who worked in London at the same time.2Following the latter’s death in 1806, the miniaturist Barry cleared up any confusion in a Morning Post advertisement: “MR. BARRY, (Miniature Painter), perceiving that the death of the late JAMES BARRY, Esq. formerly Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy, has occasioned repeated mistakes among his friends, in consequence of his having the same Christian and Surname with the deceased, finds it necessary to inform the public that he still resides at No. 57, New Bond-street”; Morning Post (London), March 27, 1806, 1. This discovery was made in 2018 by Nicolas Stogdon, former head of Christie’s print department and now a private dealer. The two Barrys probably crossed paths, the elder being a professor at the same time the younger Barry was regularly exhibiting at the Royal Academy. New research has shed light on his previously unknown life dates and unveiled details regarding his family and religious ties.

Records from the Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. reveal James Barry’s enrollment on March 21, 1774, listing his age as “18 yrs 6th last Nov.,” indicating a birthdate of November 6, 1755.3Royal Academy Collection, Archive, “Page 5 – B,” 1769–1775, ref. RAA/KEE/1/1/1/5, Royal Academy of Arts, London, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/archive/page-5-blank-page. This cannot be the historical painter James Barry (1741–1806), because he would have been too old, having joined the Academy as a member, not a student, around 1777. See “Barry, James,” Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), digitized on Wikisource, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Barry,_James. In 1783, Barry advertised himself as a miniature painter, subsequently exhibiting at the Academy two years later.4Barry exhibited in 1784–1787, 1789–1794, 1796–1809, 1816–1819, 1825, and 1827. He exhibited portraits of Mr. and Mrs. R. Barry in 1801, probably Richard Barry and his wife, Letitia. He also exhibited portraits of the “Rev. B. Wood and Mrs. C. Wood” in 1806 and “C. Wood” in 1818, probably referring to the Reverend Basil Woodd, Charles Woodd (1775–1827), and the latter’s wife, Mary (née Jupp). Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors (London: Henry Graves and George Bell and Sons, 1905), 1:132–33. He resided at 2 Lyon Terrace, Edgeware Road, from 1816 to 1825.5The British Museum provides a full list of Barry’s known addresses: “James Barry,” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG152428, accessed September 27, 2023.

A will dated November 24, 1835, belonging to James Barry of Lyon Terrace, Edgeware Road, provides additional information.6See “Will of James Barry, Gentleman of Lyon Terrace Edgeware Road, Middlesex,” November 24, 1835, PROB 11/1853/356, National Archives, Kew. The relationship between Basil George Woodd and the later mentioned Rev. Basil Woodd is not yet known, although Basil George Woodd named one of his sons Charles Henry Lardner Wood (1821–1893), which may be a nod to Dr. William Lardner (ca. 1779–1843), executor of Barry’s will. See Francis Wheatley, Portrait of a Man, called George Basil Woodd, ca. 1780, oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm), Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.676. It mentions his wife, Caroline, confirmed to be Caroline Jupp by a marriage license dated October 6, 1803.7London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P87/Js/013, London Metropolitan Archives. The witness to Barry’s will was Edward B. Jupp, Caroline Jupp’s (1775–1862) brother. But Barry interestingly lists himself as already a widower, aligning with an obituary in Gentleman’s Magazine that had reported the death of “the wife of Mr. Barry, miniature-painter” on January 12, 1803, nine months before his marriage to Jupp.8Sylvanus Urban, “Obituary, with Anecdotes, of Remarkable Persons,” The Gentleman’s Magazine 93 (January 1803): 91. His first wife may have been Jane Hemmings, whom a James Barry married on October 9, 1786.9For the marriage record, see Westminster Church of England Parish Registers, ref. STA/PR/4/7, City of Westminster Archives Centre, London. A Jane Barry was buried on January 9, 1803. The burial record does not list a date of death. London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P89/MRY1/315, London Metropolitan Archives.

Apart from leaving his prints, pictures, and jewels to Caroline, Barry mentions his brother, Richard (ca. 1765–1819),10For more information on Richard, see Rev. Charles Hole, The Early History of the Church Missionary Society for Africa and the East (London: Church Missionary Society, 1896), 240, 622. and two religious groups: the United Brethren, or Moravians, and the Naval and Military Bible Society. The former counted John Wesley (1703–1791), the founder of Methodism, among its members before he started his own ministry, while the latter was initiated by two men from Wesley’s chapel.11Wesley was formerly a member of a Moravian society before leaving the religious group after 1738 and starting his own ministry. “United Methodist Men History,” New York Conference: The United Methodist Church, accessed November 20, 2023, https://www.nyac.com/ummhistory. Barry’s spiritual connection to Wesley is reinforced by a miniature he created of the Methodist leader.12The miniature was painted in 1790, probably the last likeness captured of the famous cleric and theologian. He also probably exhibited the portrait miniature at the Royal Academy; J. Barry, Portrait of a Clergyman, in The Exhibition of the Royal Academy (London: T. Cadell, 1790), 12. See also Peter Forsaith, Image, Identity and John Wesley: A Study in Portraiture, Routledge Methodist Studies (London: Taylor and Francis, 2017), 179. Forsaith confirms that the miniature was completed by the present Barry, and not the historical painter James Barry.

Barry also documented his friend and brother-in-law, the Reverend Basil Woodd (1760–1831), by drawing him during a sermon.13Woodd was an evangelical cleric famous for his invention of evening preaching. James Barry served as treasurer of his Bentinck Chapel. “Associations in and near London: Bentinck Chapel,” Proceedings of the Church Missionary Society for Africa and the East (London: Bensley and Son, 1818), unpaginated. The drawing is erroneously attributed to John Barry (fl. 1784–1827): Portrait of the Reverend Basil Woodd, by 1827, pencil, pen and ink on cream woven paper, 8 3/4 x 7 1/4 in. (22.2 x 18.5 cm), Royal Academy of Arts, Given by Leverhulme Trust 1936, 03/5030, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/portrait-of-the-reverend-basil-woodd. These works, and others by Barry, were collected by another brother-in-law, Richard Webb Jupp (1767–1852), and later donated to the Royal Academy.14Jupp was present at Caroline’s marriage and was also executor of Richard Barry’s will, in addition to the Rev. Basil Woodd. Jupp was also a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and clerk of the Carpenters’ Company. His son was Edward Basil Jupp (1812–1877); See “Edward Basil Jupp,” The British Museum, accessed November 20, 2023, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG33366. Finally, a death notice from October 30, 1835, corroborates Barry’s birth date in late 1755, aligning with the record of his enrollment in the Royal Academy Schools: “DIED. On the 27th inst., James Barry, Esq., of Lyon-terrace, Edgeware-road, in his 79th year.”15Morning Herald, London, October 30, 1835. Since he had not yet turned eighty, this confirms that the artist was born in November or December of 1755. He was buried on November 4, according to London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P87/Mry/064, London Metropolitan Archives.

Notes

-

The confusion is likely due to Royal Academy exhibition records only ever referring to him as “J. Barry.”

-

Following the latter’s death in 1806, the miniaturist Barry cleared up any confusion in a Morning Post advertisement: “MR. BARRY, (Miniature Painter), perceiving that the death of the late JAMES BARRY, Esq. formerly Professor of Painting at the Royal Academy, has occasioned repeated mistakes among his friends, in consequence of his having the same Christian and Surname with the deceased, finds it necessary to inform the public that he still resides at No. 57, New Bond-street”; Morning Post (London), March 27, 1806, 1. This discovery was made in 2018 by Nicolas Stogdon, former head of Christie’s print department and now a private dealer. The two Barrys probably crossed paths, the elder being a professor at the same time the younger Barry was regularly exhibiting at the Royal Academy.

-

Royal Academy Collection, Archive, “Page 5 – B,” 1769–1775, ref. RAA/KEE/1/1/1/5, Royal Academy of Arts, London, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/archive/page-5-blank-page. This cannot be the historical painter James Barry (1741–1806), because he would have been too old, having joined the Academy as a member, not a student, around 1777. See “Barry, James,” Encyclopædia Britannica (1911), digitized on Wikisource, https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclopædia_Britannica/Barry,_James.

-

Barry exhibited in 1784–1787, 1789–1794, 1796–1809, 1816–1819, 1825, and 1827. He exhibited portraits of Mr. and Mrs. R. Barry in 1801, probably Richard Barry and his wife, Letitia. He also exhibited portraits of the “Rev. B. Wood and Mrs. C. Wood” in 1806 and “C. Wood” in 1818, probably referring to the Reverend Basil Woodd, Charles Woodd (1775–1827), and the latter’s wife, Mary (née Jupp). Algernon Graves, The Royal Academy of Arts: A Complete Dictionary of Contributors (London: Henry Graves and George Bell and Sons, 1905), 1:132–33.

-

The British Museum provides a full list of Barry’s known addresses: “James Barry,” The British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG152428, accessed September 27, 2023.

-

See “Will of James Barry, Gentleman of Lyon Terrace Edgeware Road, Middlesex,” November 24, 1835, PROB 11/1853/356, National Archives, Kew. The relationship between Basil George Woodd and the later mentioned Rev. Basil Woodd is not yet known, although Basil George Woodd named one of his sons Charles Henry Lardner Wood (1821–1893), which may be a nod to Dr. William Lardner (ca. 1779–1843), executor of Barry’s will. See Francis Wheatley, Portrait of a Man, called George Basil Woodd, ca. 1780, oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm), Yale Center for British Art, B1981.25.676.

-

London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P87/Js/013, London Metropolitan Archives. The witness to Barry’s will was Edward B. Jupp, Caroline Jupp’s (1775–1862) brother.

-

Sylvanus Urban, “Obituary, with Anecdotes, of Remarkable Persons,” The Gentleman’s Magazine 93 (January 1803): 91.

-

For the marriage record, see Westminster Church of England Parish Registers, ref. STA/PR/4/7, City of Westminster Archives Centre, London. A Jane Barry was buried on January 9, 1803. The burial record does not list a date of death. London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P89/MRY1/315, London Metropolitan Archives.

-

For more information on Richard, see Rev. Charles Hole, The Early History of the Church Missionary Society for Africa and the East (London: Church Missionary Society, 1896), 240, 622.

-

Wesley was formerly a member of a Moravian society before leaving the religious group after 1738 and starting his own ministry. “United Methodist Men History,” New York Conference: The United Methodist Church, accessed November 20, 2023, https://www.nyac.com/ummhistory.

-

The miniature was painted in 1790, probably the last likeness captured of the famous cleric and theologian. He also probably exhibited the portrait miniature at the Royal Academy; J. Barry, Portrait of a Clergyman, in The Exhibition of the Royal Academy (London: T. Cadell, 1790), 12. See also Peter Forsaith, Image, Identity and John Wesley: A Study in Portraiture, Routledge Methodist Studies (London: Taylor and Francis, 2017), 179. Forsaith confirms that the miniature was completed by the present Barry, and not the historical painter James Barry.

-

Woodd was an evangelical cleric famous for his invention of evening preaching. James Barry served as treasurer of his Bentinck Chapel. “Associations in and near London: Bentinck Chapel,” Proceedings of the Church Missionary Society for Africa and the East (London: Bensley and Son, 1818), unpaginated. The drawing is erroneously attributed to John Barry (fl. 1784–1827): Portrait of the Reverend Basil Woodd, by 1827, pencil, pen and ink on cream woven paper, 8 3/4 x 7 1/4 in. (22.2 x 18.5 cm), Royal Academy of Arts, Given by Leverhulme Trust 1936, 03/5030, https://www.royalacademy.org.uk/art-artists/work-of-art/portrait-of-the-reverend-basil-woodd.

-

Jupp was present at Caroline’s marriage and was also executor of Richard Barry’s will, in addition to the Rev. Basil Woodd. Jupp was also a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and clerk of the Carpenters’ Company. His son was Edward Basil Jupp (1812–1877); See “Edward Basil Jupp,” The British Museum, accessed November 20, 2023, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG33366.

-

Morning Herald, London, October 30, 1835. Since he had not yet turned eighty, this confirms that the artist was born in November or December of 1755. He was buried on November 4, according to London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P87/Mry/064, London Metropolitan Archives.

John Thomas Barber Beaumont (English, 1774–1841)

Work by This Artist

John Thomas Barber Beaumont was a distinguished artist and entrepreneur. His early years remain uncertain, with some reports suggesting he came from a modest home and others stating he came from “reasonably affluent circumstances.”1David Anthony Beaumont, Barber Beaumont (London: Witherby, 1999), 1. The author, a distant relative of the artist, endeavored to compile as much information as he could about Barber Beaumont in the wake of the destruction of nearly all of the family papers. The author utilized original sources; however, he does not provide footnotes for these sources. He began his artistic career as a student at London’s Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. in 1791, where he regularly exhibited miniature paintings from 1794 to 1806.2Much of the biographical information for this entry has come from Robin Pearson, “John Thomas Barber Beaumont (c. 1774–1841),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/1877; and Beaumont, Barber Beaumont. He served as miniature painter to Prince Edward, Duke of Kent and Strathearn; Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany; and the Prince of Wales. His pupils included painter and engraver Henry Thomas Alken (1785–1851). In 1796, he married Sophia Sarah Schabner, and they had ten children. Perhaps as a way to distinguish himself from the painter Thomas Barber (1771–1843), John Thomas Barber added the name “Beaumont” to his surname after 1812.3This is the author’s observation. Other scholars, including Robin Pearson, do not offer a reason for Barber’s adoption of the additional surname “Beaumont” and/or state that the reason is unknown.

Barber Beaumont’s interests extended beyond art. In 1803, he published the acclaimed guidebook A Tour through South Wales4John Thomas Barber, A Tour through South Wales and Monmouthshire Etc. (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1803). and wrote on various other subjects as well, including the titles Life Insurance (1814), Provident and Parish Banks (1816), Public House Licensing (1816–18), Criminal Jurisprudence (1821), and Parliamentary Reform (1830). He founded the renowned rifle corps, The Duke of Cumberland’s Sharpshooters, during the Napoleonic Wars: A series of major global conflicts fought during Napoleon Bonaparte’s imperial rule over France, from 1805 to 1815..

As an entrepreneur, Barber Beaumont established successful insurance ventures. The Provident Life Office (1806) and County Fire Office (1807) became leading fire insurers through his strategic leadership. He also served as a magistrate for Middlesex and Westminster beginning in 1820.

Barber Beaumont was a supporter of Queen Caroline, the estranged wife of King George IV, which earned the painter a radical reputation. He invested in Mile End, a neighborhood of London, acquiring property and founding the Philosophical Institution there in 1840. Beaumont bequeathed thirteen thousand pounds to the institution, which evolved into Queen Mary College.5See H. A. Grueber, “English Personal Medals From 1760,” Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society 7 (1887): 265–67.

He passed away on May 15, 1841, at the County Fire Office in Regent Street. Initially buried at Stepney in the East End of London, he was reinterred at Kensal Green cemetery in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.6When the East London cemetery closed, his body was removed to Kensal Green. The tombstone was left abandoned and eventually taken to Queen Mary’s College, where it is embedded in the wall of the Rotunda in the Queen’s Building. See David Anthony Beaumont, Barber Beaumont, 187. Beaumont’s legacy is one of artistic excellence, entrepreneurial achievements, and a commitment to intellectual pursuits.

Notes

-

David Anthony Beaumont, Barber Beaumont (London: Witherby, 1999), 1. The author, a distant relative of the artist, endeavored to compile as much information as he could about Barber Beaumont in the wake of the destruction of nearly all of the family papers. The author utilized original sources; however, he does not provide footnotes for these sources.

-

Much of the biographical information for this entry has come from Robin Pearson, “John Thomas Barber Beaumont (c. 1774–1841),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/1877; and Beaumont, Barber Beaumont.

-

This is the author’s observation. Other scholars, including Robin Pearson, do not offer a reason for Barber’s adoption of the additional surname “Beaumont” and/or state that the reason is unknown.

-

John Thomas Barber, A Tour through South Wales and Monmouthshire Etc. (London: T. Cadell and W. Davies, 1803).

-

See H. A. Grueber, “English Personal Medals From 1760,” Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society 7 (1887): 265–67.

-

When the East London cemetery closed, his body was removed to Kensal Green. The tombstone was left abandoned and eventually taken to Queen Mary’s College, where it is embedded in the wall of the Rotunda in the Queen’s Building. See David Anthony Beaumont, Barber Beaumont, 187.

Charles Boit (Swedish, worked in England, 1662–1727)

Work by This Artist

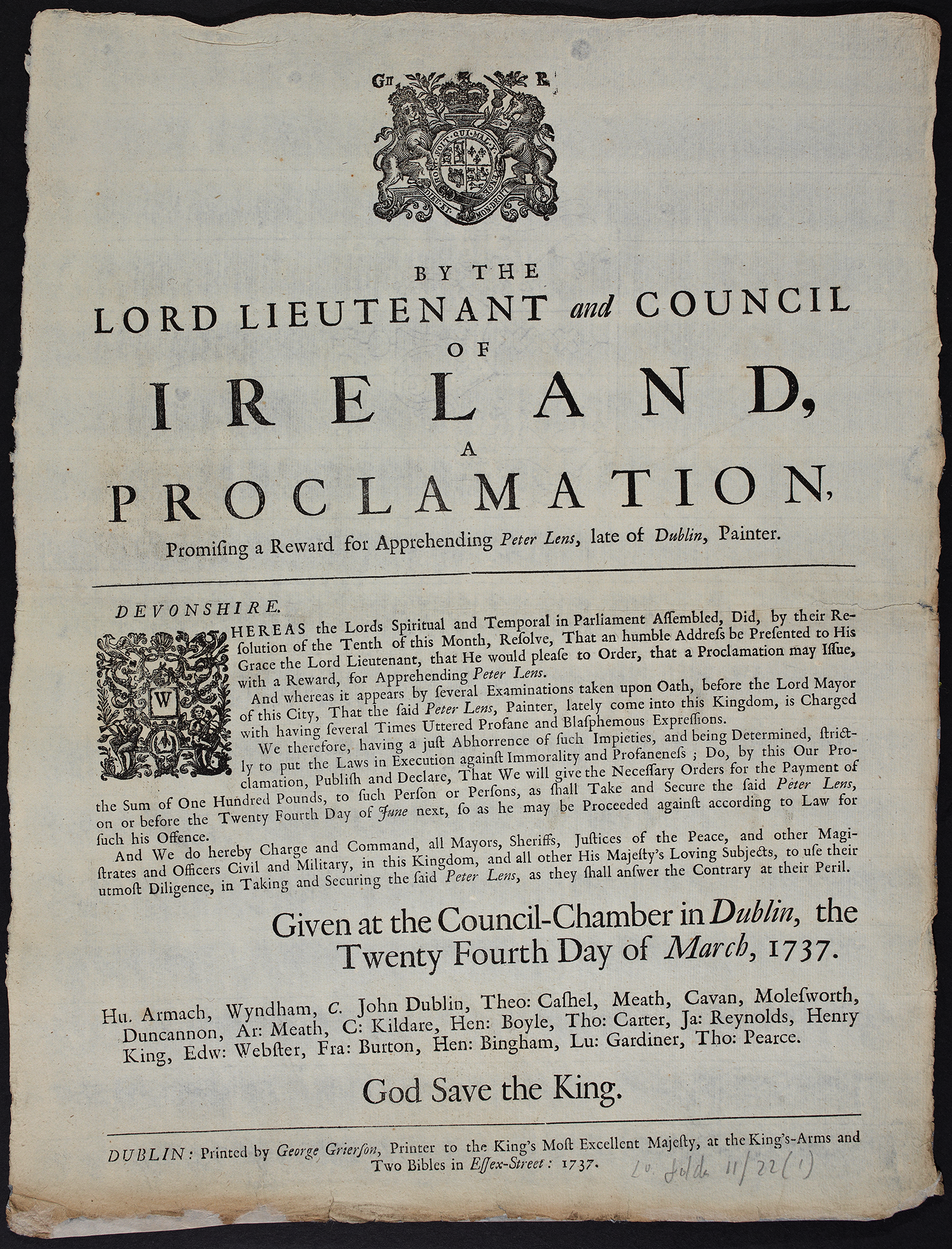

Born in Stockholm to a French Huguenot: A French Protestant who followed the teachings of John Calvin (1509–1564). Protestantism and particularly Calvinism were strongly opposed by the French Catholic government. Huguenots faced centuries of persecution in France, and the vast majority immigrated to other countries, including Great Britain and Switzerland, by the early eighteenth century. Due to their belief that wealth acquired through honest work was godly, Huguenot refugees in these countries brought with them a strong tradition of skilled artmaking and craftsmanship, particularly in silver and goldsmithing, silk weaving, and watchmaking. See also Edict of Nantes. family, Charles Boit originally trained as a goldsmith. After three formative months in Paris in 1682—where he may have studied with enameller Jean Toutin (1578–1644), one of the first artists to make enamel: Enamel miniatures originated in France before their introduction to the English court by enamellist Jean Petitot. Enamel was prized for its gloss and brilliant coloring—resembling the sheen and saturation of oil paintings—and its hardiness in contrast to the delicacy of light sensitive, water soluble miniatures painted with watercolor. Enamel miniatures were made by applying individual layers of vitreous pigment, essentially powdered glass, to a metal support, often copper but sometimes gold or silver. Each color required a separate firing in the kiln, beginning with the color that required the highest temperature; the more colors, the greater risk that the miniature would be damaged by the process. The technique was difficult to master, even by skilled practitioners, leading to its increased cost in contrast with watercolor miniatures. portrait miniatures—Boit took up the art of enameling. He may also have received training in Sweden from the French enameller Pierre Signac (d. 1684).1Erika Speel, Painted Enamels: An Illustrated Survey 1500–1920 (Aldershot, UK: Lund Humphries, 2008), 194. For more on Boit, see Gunnar W. Lundberg, Charles Boit, 1662–1727, Émailleur-miniaturiste suédois: Biographie et catalogue critiques (Paris: Centre culturel suédois, 1987). In 1687, Boit departed for England. According to George Vertue, Boit initially struggled to get commissions and worked in the countryside as a drawing master for the country gentry.2During his time in the countryside, Boit—according to Vertue and Horace Walpole, at least—may have spent two years in prison after seducing and attempting to marry one of his students. Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1849), 634. The support of a fellow Swede, portraitist Michael Dahl (1659–1703), eventually launched Boit’s career as one of the premiere miniaturists in England.

Boit was appointed court enameller to William III in 1696.3Vanessa Remington, “Boit, Charles (1662–1727), miniature painter,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/2783. Boit insisted that his title be changed from the standard “limner: One who limns. See also limning.” to “enameller,” reflecting not only his pride in mastering this difficult medium and elevating its status in England, but also signaling the fundamental shift at that time from an understanding of miniatures, or “limning: “Limning” was derived from the Latin word luminare, meaning to illuminate, and the term also became associated with the Latin miniare, referring to the red lead used in illuminated manuscripts, which were also called limnings. Limning developed as an art form separate from manuscript illumination after the inception of the printing press, when books became more utilitarian and less precious. Eventually limning became associated with other diminutive two-dimensional artworks, such as miniatures, leading to the misnomer that “miniature” refers to the size of the object and not its origins in manuscript illumination. Limning is distinct from painting not only by its medium, with the use of watercolor and vellum traditionally used for manuscript illuminations, but also by the typically small size of such works.,” as artworks solely executed with watercolor: A sheer water-soluble paint prized for its luminosity, applied in a wash to light-colored surfaces such as vellum, ivory, or paper. Pigments are usually mixed with water and a binder such as gum arabic to prepare the watercolor for use. See also gum arabic. on vellum: A fine parchment made of calfskin. A thin sheet of vellum was typically mounted with paste on a playing card or similar card support. See also table-book leaf. to include enamels and watercolors painted on ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures..4Marjorie E. Wieseman, “Bernard Lens’s Miniatures for the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 9, no. 1 (Winter 2017), https://doi.org/10.5092/jhna.2018.10.2.3. While all previous court miniaturists had been appointed Limner in Ordinary to the king, after Boit requested the change to his title, all subsequent appointees were referred as “Enameller in Ordinary”, even if they worked in watercolor, until Samuel Finney’s appointment as Enamel and Miniature Painter to Queen Charlotte in 1763, likely due to the increasing obscurity of limning. Katherine Coombs, The Portrait Miniature in England (London: V&A Publications, 1998), 89.

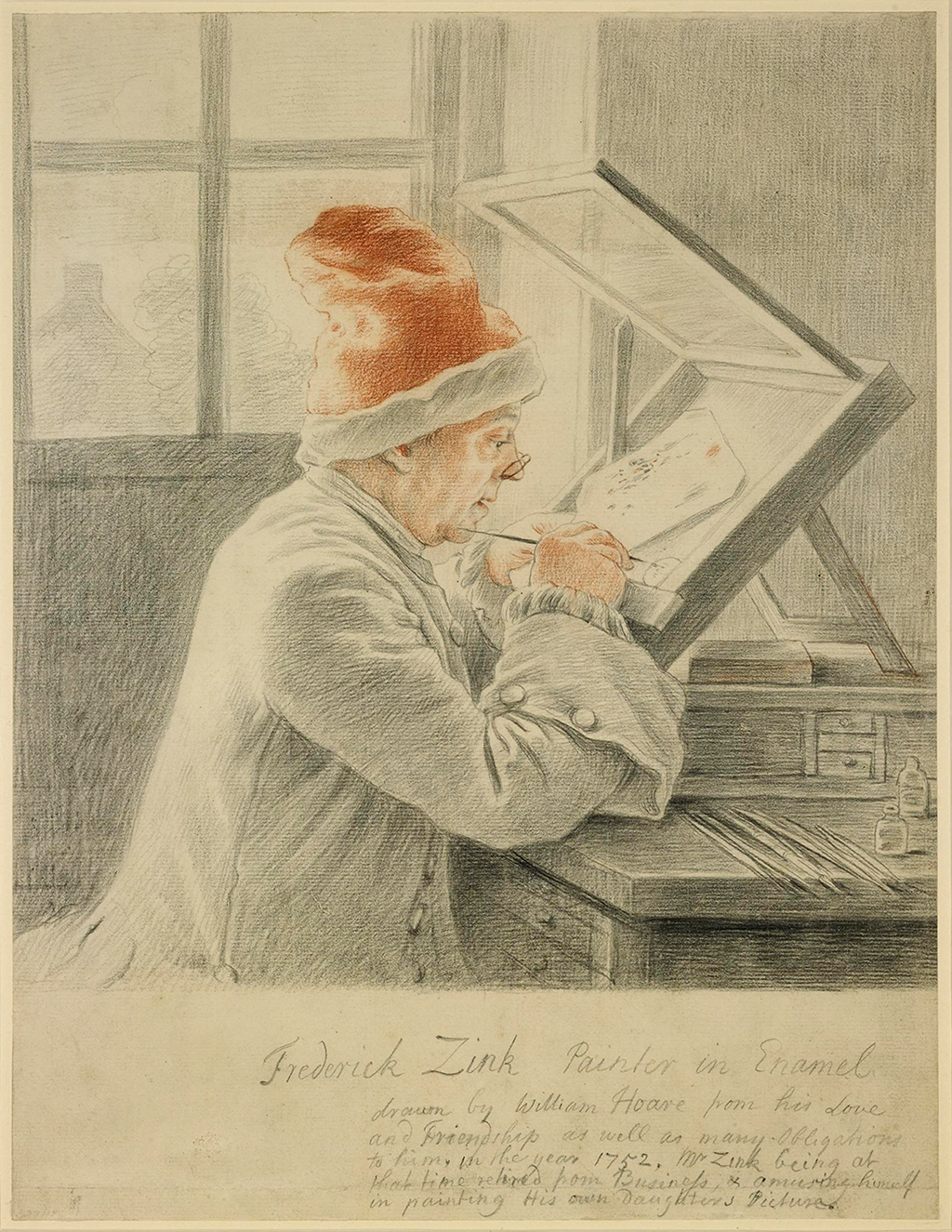

Boit was talented and commanded high prices, leading a scandalized Horace Walpole to opine that his fees were “not to be believed.”5Boit charged thirty guineas “for a lady’s head,” and “double that sum” for a larger miniature. For more ambitious projects, he charged 500 guineas or more, as in the case of the thousand-guinea advance that was forwarded by Prince George for the large royal commission mentioned later in this paragraph. Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting, 634. In spite of Boit’s success, his lofty ambitions and extravagance led him into financial arrears. His unsuccessful efforts to fulfill a royal commission for an unusually large enamel group portrait led him to flee to France in 1714.6Remington, “Boit, Charles.” Elected to the French Royal Academy in 1717, Boit died in Paris a decade later, besieged by creditors.7Boit was a Protestant and foreign national, albeit of French parentage, so his election to the esteemed and insular French Academy was somewhat unusual and attests to his skill and international reputation. Upon his arrival in France, his patrons included Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, who would rule France as regent beginning in 1715, and Tsar Peter the Great. Graham Reynolds, “Boit, Charles,” Grove Art Online, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T009653. Boit’s legacy lived on in England through his student Christian Friedrich Zincke (ca. 1684–1767).

Notes

-

Erika Speel, Painted Enamels: An Illustrated Survey 1500–1920 (Aldershot, UK: Lund Humphries, 2008), 194. For more on Boit, see Gunnar W. Lundberg, Charles Boit, 1662–1727, Émailleur-miniaturiste suédois: Biographie et catalogue critiques (Paris: Centre culturel suédois, 1987).

-

During his time in the countryside, Boit—according to Vertue and Horace Walpole, at least—may have spent two years in prison after seducing and attempting to marry one of his students. Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1849), 634.

-

Vanessa Remington, “Boit, Charles (1662–1727), miniature painter,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/2783.

-

Marjorie E. Wieseman, “Bernard Lens’s Miniatures for the Duke and Duchess of Marlborough,” Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 9, no. 1 (Winter 2017), https://doi.org/10.5092/jhna.2018.10.2.3. While all previous court miniaturists had been appointed Limner in Ordinary to the king, after Boit requested the change to his title, all subsequent appointees were referred as “Enameller in Ordinary,” even if they worked in watercolor, until Samuel Finney’s appointment as Enamel and Miniature Painter to Queen Charlotte in 1763, likely due to the increasing obscurity of limning. Katherine Coombs, The Portrait Miniature in England (London: V&A Publications, 1998), 89.

-

Boit charged thirty guineas “for a lady’s head,” and “double that sum” for a larger miniature. For more ambitious projects, he charged 500 guineas or more, as in the case of the thousand-guinea advance that was forwarded by Prince George for the large royal commission mentioned later in this paragraph. Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting, 634.

Remington, “Boit, Charles.”

-

Boit was a Protestant and foreign national, albeit of French parentage, so his election to the esteemed and insular French Academy was somewhat unusual and attests to his skill and international reputation. Upon his arrival in France, his patrons included Philippe, Duc d’Orléans, who would rule France as regent beginning in 1715, and Tsar Peter the Great. Graham Reynolds, “Boit, Charles,” Grove Art Online, 2003, https://doi.org/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T009653.

Henry Bone (English, 1755–1834)

Work by This Artist

Henry Bone, After Sir Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of George IV when Prince Regent, 1821

The son of a woodcarver and cabinetmaker from Truro, Cornwall, Henry Bone was born February, 6, 1755. He began work as a miniature painter following a short career in Plymouth painting on hard-paste porcelain for local manufacturers. He apprenticed with porcelain painter Richard Champion (English, 1743–1791) in Bristol before moving to London in 1779, reportedly with one guinea in his pocket and five pounds borrowed from a friend.1R. B. J. Walker, “Henry Bone,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/2836. Bone’s first miniatures on ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. date from this year, including a portrait of Elizabeth Van der Meulen, whom he married on January 24, 1780.2Henry Bone, Elizabeth Vandermeulen, the Artist’s Wife, 1779, 1 3/4 x 1 3/8 in. (4.5 x 3.5 cm), Victoria and Albert Museum, London, P.23-1936, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1070092/elizabeth-vandermeulen-the-artists-wife-portrait-miniature-henry-bone/. They had numerous children, five of whom—including Henry Pierce Bone (1779–1855) and two grandchildren—also became miniaturists.3His children helped in the production of a large body of enamel portraits, mostly after well-known portraits by Renaissance and Baroque painters as well as near contemporaries. These are signed with the monograms “HB,” “WB,” and “HPB,” almost always inscribed in puce against light blue counter-enamels. Henry Bone’s children were Henry Pierce (1770–1855), Peter Joseph (1785–1814), Robert Trewick (1790–1840?), William I (active 1815–1843), Thomas Mein (b. 1798), and Samuel Vallis (active 1819–1824). The ready market for these works in the early 1800s—in tandem with a steady stream of commissions for enamel portraits from the Prince of Wales, among other aristocratic patrons—facilitated Bone’s ability to move his growing family from his small house on Hanover Street to a larger house at 15 Berners Street, east of Mayfair, which is now known as Soho. For more on Bone, including a complete family tree, see R. B. J. Walker, “Henry Bone’s Pencil Drawings in the National Portrait Gallery,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 61 (1999): 305, 305n5. Bone turned exclusively to enamel: Enamel miniatures originated in France before their introduction to the English court by enamellist Jean Petitot. Enamel was prized for its gloss and brilliant coloring—resembling the sheen and saturation of oil paintings—and its hardiness in contrast to the delicacy of light sensitive, water soluble miniatures painted with watercolor. Enamel miniatures were made by applying individual layers of vitreous pigment, essentially powdered glass, to a metal support, often copper but sometimes gold or silver. Each color required a separate firing in the kiln, beginning with the color that required the highest temperature; the more colors, the greater risk that the miniature would be damaged by the process. The technique was difficult to master, even by skilled practitioners, leading to its increased cost in contrast with watercolor miniatures. around 1803, becoming one of the most sought-after enamellists of his day.

Bone was largely self-taught, and his technique began with a preparatory pencil drawing of his subject on squared paper. He traced this in red chalk onto an enamel surface that he then fired in order to fix the chalk outline. His process evolved through trial and error, undoubtably aided by his formative training in the porcelain industry. This facilitated his ability to experiment with size, coloring, and firing temperatures,4This knowledge also helped him avoid warping and cracking during the heating and cooling process. Walker, “Henry Bone’s Pencil Drawings in the National Portrait Gallery,” 307. resulting in the largest known enamel on copper miniature, after Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne.5The miniature, which measures 15 15/16 x 18 1/8 inches, is in the collections of the Cleveland Museum of Art, 2013.51, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/2013.51. Its composition is based on Titian’s (Venetian, ca. 1488–1576) Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1503; National Gallery, London), and it took Bone three years to produce.

Principally a copyist, Bone exhibited more than 240 miniatures at the Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. between 1781 and 1832, when his eyesight began to falter. He also painted designs for lockets, watches, and jewelry. He was elected Associate to the Royal Academy in 1801, the same year he was appointed enamel painter to the Prince of Wales. He later held the same position for George III, George IV, and William IV. He achieved full academician status in 1811. He died of paralysis in Clarendon Square, Somerstown, London, on December 17, 1834.6Walker, “Henry Bone.”

Notes

-

R. B. J. Walker, “Henry Bone,” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004) https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/2836.

-

Henry Bone, Elizabeth Vandermeulen, the Artist’s Wife, 1779, 1 3/4 x 1 3/8 in. (4.5 x 3.5 cm), Victoria and Albert Museum, London, P.23-1936, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1070092/elizabeth-vandermeulen-the-artists-wife-portrait-miniature-henry-bone/.

-

His children helped in the production of a large body of enamel portraits, mostly after well-known portraits by Renaissance and Baroque painters as well as near contemporaries. These are signed with the monograms “HB,” “WB,” and “HPB,” almost always inscribed in puce against light blue counter-enamels. Henry Bone’s children were Henry Pierce (1770–1855), Peter Joseph (1785–1814), Robert Trewick (1790–1840?), William I (active 1815–1843), Thomas Mein (b. 1798), and Samuel Vallis (active 1819–1824). The ready market for these works in the early 1800s—in tandem with a steady stream of commissions for enamel portraits from the Prince of Wales, among other aristocratic patrons—facilitated Bone’s ability to move his growing family from his small house on Hanover Street to a larger house at 15 Berners Street, east of Mayfair, which is now known as Soho. For more on Bone, including a complete family tree, see R. B. J. Walker, “Henry Bone’s Pencil Drawings in the National Portrait Gallery,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 61 (1999): 305, 305n5.

-

This knowledge also helped him avoid warping and cracking during the heating and cooling process. Walker, “Henry Bone’s Pencil Drawings in the National Portrait Gallery,” 307.

-

The miniature, which measures 15 15/16 x 18 1/8 inches, is in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, 2013.51, https://www.clevelandart.org/art/2013.51. Its composition is based on Titian’s (Venetian, ca. 1488–1576) Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1503; National Gallery, London), and it took Bone three years to produce.

Walker, “Henry Bone.”

Henry Jacob Burch (English, 1762–after 1834)

Work by This Artist

Henry Jacob Burch was the son of Edward Burch (1730–1814),1Typically listed as ca. 1730–ca. 1814, Edward’s life dates have been confirmed through genealogical research: London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. DL/T/066/006, London Metropolitan Archives. For a more substantial biography on Edward, see Gertrud Seidmann, “Burch, Edward,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 8:724–25. a well-known gem and seal engraver and a self-taught miniaturist.2Henry Jacob Burch is sometimes referred to as Henry Burch or Henry Burch Junior. See George Bernard Hughes and Therle Hughes, Collecting Miniature Antiques: A Guide for Collectors (London: Heinemann, 1973), 16. The Nelson-Atkins previously referred to this artist as Henry Burch Junior. Daphne Foskett, in Collecting Miniatures (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club, 1979), 399, refers to the artist as Henry Jacob Burch Junior. Edward worked as a waterman on the Thames before pursuing a career as an artist, but despite his success at the latter, he was so impoverished in old age that the Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. appointed him librarian in order to provide him with an income.3Two of his seals were used by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792). Librarian of the Royal Academy was a sinecure post, one that required little responsibility, according to the British Museum, “Edward Burch,” British Museum website, accessed August 30, 2022, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG66427. Edward’s insolvency coincided with that of his son; Henry Jacob Burch’s own financial difficulties in the field of portrait miniatures had made him unable to provide for his elderly father.4The two were likely close, based on the portrait of Edward that Henry Jacob Burch exhibited in 1814, the year his father died: The Royal Academy, The Exhibition of the Royal Academy (London: B. McMillan, 1814): 21, no. 386, as Henry Burch, Portrait of the late E. Burch, Esq. R.A. and Librarian of the Royal Academy.

While some scholars give Henry’s year of birth as 1763, a baptismal record confirms that he was baptized on December 30, 1762, to Edward and Anne Burch.5“Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials: City of London: St. Bride Fleet Street,” ref. P69/BRI/A/007/MS06541/001, London Metropolitan Archives. Henry Jacob may have had a sister, Anne Mary, born on May 24, 1761, as well as a brother, Edward Burch (b. 1772). Henry followed his father’s career in the arts and enrolled in the Royal Academy Schools on March 25, 1779.6“Register of Admission of Students: Page 6–B,” ref. RAA/KEE/1/1/1/6, Royal Academy Archives, London. Although he did not become an academician like his father, he frequently exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1787 and 1831.7Daphne Foskett, Miniatures: Dictionary and Guide (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club, 1987), 344; Seidmann, “Burch, Edward,” 725. Specifically, he exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1787 to 1790, 1792 to 1795, 1797 to 1804, 1807 to 1810, 1812, 1814 to 1815, 1817 to 1821, 1827, and 1831, according to digitized exhibition catalogues at the Royal Academy, https://chronicle250.com. Burch married Elizabeth Beresford on December 6, 1784, with his father listed as a witness.8London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P89/MRY1/171, London Metropolitan Archives. Burch and his wife had at least five children together, none of whom are known to have continued the family tradition in miniature painting or seal engraving.9Edward James, born September 2, 1785; Shovil, born October 29, 1788; Henry, born February 3, 1790; Mary Beresford, born March 26, 1792; and James Beresford, born November 21, 1793. All their birth records can be found in Westminster Church of England Parish Registers, ref. STA/PR/1/3, City of Westminster Archives Centre. A fire in 1793 destroyed the Burches’ house on Rathbone Place, forcing a move to 66 Newman Street, a neighborhood near the British Museum that was popular among artists and known as “Artists’ Street.”10Foskett, Miniatures, 344; “Insured: Henry Jacob Burch, 66 Newman Street, miniature painter,” March 12, 1794, ref. MS 11936/397/626218, London Metropolitan Archives; Mary L. Shannon, “Artists’ Street: Thomas Stothard, R. H. Cromek, and Literary Illusion on London’s Newman Street,” in Romanticism and Illustration, ed. Ian Haywood, Susan Matthews, and Mary L. Shannon, online edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019): 243, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108348829.011. The family moved often, according to addresses listed during Burch’s years exhibiting at the Royal Academy.

Burch rarely signed his work, making it extremely difficult to pinpoint his style with much consistency. Some scholars compare his style and technique to those of William Wood (English, 1769–1810), although Burch’s portraits are often painted with more assurance and a more vibrant color palette.11Foskett, Miniatures, 344. His repertoire, despite problems with attribution, includes many portrait miniatures of children.12See Henry Jacob Burch*, Portrait Miniature of an Unknown Boy*, ca. 1780–1834, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/4 x 1 3/4 in. (5.7 x 4.5 cm), Victoria and Albert Museum, EVANS.252, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1070159/portrait-miniature-of-an-unknown-miniature-henry-jacob-burch/; and Henry Jacob Burch, Portrait Miniature of a Young Girl, ca. 1785–1835, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 x 1 15/16 in. (6.4 x 4.9 cm), Victoria and Albert Museum, P.157-1929, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1070112/portrait-miniature-of-a-young-portrait-miniature-henry-jacob-burch/. Burch’s year of death is often listed as 1834, but this has yet to be confirmed through death records.

Notes

-

Typically listed as ca. 1730–ca. 1814, Edward’s life dates have been confirmed through genealogical research: London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. DL/T/066/006, London Metropolitan Archives. For a more substantial biography on Edward, see Gertrud Seidmann, “Burch, Edward,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 8:724–25.

-

Henry Jacob Burch is sometimes referred to as Henry Burch or Henry Burch Junior. See George Bernard Hughes and Therle Hughes, Collecting Miniature Antiques: A Guide for Collectors (London: Heinemann, 1973), 16. The Nelson-Atkins previously referred to this artist as Henry Burch Junior. Daphne Foskett, in Collecting Miniatures (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club, 1979), 399, refers to the artist as Henry Jacob Burch Junior.

-

Two of his seals were used by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792). Librarian of the Royal Academy was a sinecure post, one that required little responsibility, according to the British Museum, “Edward Burch,” British Museum website, accessed August 30, 2022, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/term/BIOG66427.

-

The two were likely close, based on the portrait of Edward that Henry Jacob Burch exhibited in 1814, the year his father died: The Royal Academy, The Exhibition of the Royal Academy (London: B. McMillan, 1814): 21, no. 386, as Henry Burch, Portrait of the late E. Burch, Esq. R.A. and Librarian of the Royal Academy.

-

“Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials: City of London: St. Bride Fleet Street,” ref. P69/BRI/A/007/MS06541/001, London Metropolitan Archives. Henry Jacob may have had a sister, Anne Mary, born on May 24, 1761, as well as a brother, Edward Burch (b. 1772).

-

“Register of Admission of Students: Page 6–B,” ref. RAA/KEE/1/1/1/6, Royal Academy Archives, London.

-

Daphne Foskett, Miniatures: Dictionary and Guide (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club, 1987), 344; Seidmann, “Burch, Edward,” 725. Specifically, he exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1787 to 1790, 1792 to 1795, 1797 to 1804, 1807 to 1810, 1812, 1814 to 1815, 1817 to 1821, 1827, and 1831, according to digitized exhibition catalogues at the Royal Academy, https://chronicle250.com.

-

London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P89/MRY1/171, London Metropolitan Archives.

-

Edward James, born September 2, 1785; Shovil, born October 29, 1788; Henry, born February 3, 1790; Mary Beresford, born March 26, 1792; and James Beresford, born November 21, 1793. All their birth records can be found in Westminster Church of England Parish Registers, ref. STA/PR/1/3, City of Westminster Archives Centre.

-

Foskett, Miniatures, 344; “Insured: Henry Jacob Burch, 66 Newman Street, miniature painter,” March 12, 1794, ref. MS 11936/397/626218, London Metropolitan Archives; Mary L. Shannon, “Artists’ Street: Thomas Stothard, R. H. Cromek, and Literary Illusion on London’s Newman Street,” in Romanticism and Illustration, ed. Ian Haywood, Susan Matthews, and Mary L. Shannon, online edition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019): 243, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108348829.011. The family moved often, according to addresses listed during Burch’s years exhibiting at the Royal Academy.

-

Foskett, Miniatures, 344.

-

See Henry Jacob Burch, Portrait Miniature of an Unknown Boy, ca. 1780–1834, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/4 x 1 3/4 in. (5.7 x 4.5 cm), Victoria and Albert Museum, EVANS.252, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1070159/portrait-miniature-of-an-unknown-miniature-henry-jacob-burch/; and Henry Jacob Burch, Portrait Miniature of a Young Girl, ca. 1785–1835, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 x 1 15/16 in. (6.4 x 4.9 cm), Victoria and Albert Museum, P.157-1929, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O1070112/portrait-miniature-of-a-young-portrait-miniature-henry-jacob-burch/.

C

C. Charlie (French)

Work by This Artist

George Chinnery (English, 1774–1852)

Work by This Artist

Born in London on January 5, 1774, George Chinnery was the sixth of seven children of William Chinnery (1741–1803) and Elizabeth Bassett (d. 1812). His father and paternal grandfather were calligraphers, and his father also exhibited portraits at the Free Society of Artists in London in 1764 and 1766. Chinnery probably received his earliest artistic instruction from his father before submitting a miniature to the Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. exhibition in 1791, enrolling in its school a year later. From 1791 to 1795 he exhibited twenty-one portraits at its annual exhibitions before leaving for Dublin in 1796.1For biographical information on George Chinnery, see Patrick Connor, “Chinnery, George” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, last updated May 24, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/5311. See also Walter Strickland George, A Dictionary of Irish Artists, vol. 1, A to K (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012; originally published 1913), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139382106.

In Dublin, Chinnery expanded his artistic repertoire and the scale of his work to include large landscapes and portraits in oils. He married his landlord’s daughter, Marianne Vigne (1776/7–1865), in 1799.2In Dublin, Chinnery stayed with the family of the jeweler James Vigne at 27 College Green. On April 19, 1799, he married Vigne’s younger daughter, Marianne; see Connor, “Chinnery, George.” While they may have planned to stay in Dublin, the abolition of the Irish parliament in 1800 led to the exodus of many of the city’s wealthier inhabitants, threatening the artist’s livelihood. In 1802, at the age of twenty-eight, Chinnery received permission from the Honourable East India Company (HEIC): A British joint-stock company founded in 1600 to trade in the Indian Ocean region. The company accounted for half the world’s trade from the 1750s to the early 1800s, including items such as cotton, silk, opium, and spices. It later expanded to control large parts of the Indian subcontinent by exercising military and administrative power. to move to Madras, India, to work as a painter.3Although Chinnery started out in Madras, he eventually moved to Calcutta, where he spent the largest part of his Indian career. For a more in-depth look at this phase of his career as well as his sojourn to China, see P. R. M. Conner, George Chinnery, 1774–1852: Artist of India and the China Coast (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club, 1993). He spent twenty-three years there, moving to China in 1825 to escape debts of more than thirty thousand rupees. He spent twenty-eight years in Macau, specializing in views of the community’s daily life. Chinnery’s style greatly influenced the Chinese artists who depicted the Canton trade system for the foreign export market.4For more on the Chinese context during this period, see Peter C. Perdue, “The Artists’ Narrow World,” in Rise and Fall of the Canton Trade System: China in the World (1700–1860s) (Cambridge, MA: MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2009), https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/rise_fall_canton_01/cw_essay04.html. He died of a stroke in Macau on May 30, 1852, having spent his later years living in impoverished circumstances.5Patrick Connor noted that his friend and doctor Thomas Boswall Watson performed an autopsy on Chinnery’s body; an examination of the brain revealed that he died of a stroke. See Connor, “Chinnery, George.” In a separate source, Connor noted that in Chinnery’s later years “the artist lived in straitened circumstances,” and that while he “remained devoted to his work, . . . portraiture was no longer his mainstay.” See Patrick Conner, “George Chinnery Comes Home,” review of The Flamboyant Mr Chinnery (1774–1852)—an English Artist in India and China, Asia House, London, International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter, no. 58 (Autumn/Winter 2011): 48, https://www.iias.asia/sites/default/files/nwl_article/2019-05/IIAS_NL58_48.pdf.

Notes

-

For biographical information on George Chinnery, see Patrick Connor, “Chinnery, George” in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, last updated May 24, 2007, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/5311. See also Walter Strickland George, A Dictionary of Irish Artists, vol. 1, A to K (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012; originally published 1913), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139382106.

-

In Dublin, Chinnery stayed with the family of the jeweler James Vigne at 27 College Green. On April 19, 1799, he married Vigne’s younger daughter, Marianne; see Connor, “Chinnery, George.”

-

Although Chinnery started out in Madras, he eventually moved to Calcutta, where he spent the largest part of his Indian career. For a more in-depth look at this phase of his career as well as his sojourn to China, see P. R. M. Conner, George Chinnery, 1774–1852: Artist of India and the China Coast (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club, 1993).

-

For more on the Chinese context during this period, see Peter C. Perdue, “The Artists’ Narrow World,” in Rise and Fall of the Canton Trade System: China in the World (1700–1860s) (Cambridge, MA: MIT Visualizing Cultures, 2009), https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/rise_fall_canton_01/cw_essay04.html.

-

Patrick Connor noted that Chinnery’s friend and doctor Thomas Boswall Watson performed an autopsy on Chinnery’s body; an examination of the brain revealed that he died of a stroke. See Connor, “Chinnery, George.” In a separate source, Connor noted that in Chinnery’s later years “the artist lived in straitened circumstances,” and that while he “remained devoted to his work, . . . portraiture was no longer his mainstay.” See Patrick Conner, “George Chinnery Comes Home,” review of The Flamboyant Mr Chinnery (1774–1852)—an English Artist in India and China, Asia House, London, International Institute for Asian Studies Newsletter, no. 58 (Autumn/Winter 2011): 48, https://www.iias.asia/sites/default/files/nwl_article/2019-05/IIAS_NL58_48.pdf.

Samuel Collins (English, ca. 1735–1775)

Work by This Artist

Samuel Cooper (English, ca. 1608–1672)

Works by This Artist

Samuel Cooper, Portrait of a Woman, Probably Miss Alice Fanshawe, 1647

Samuel Cooper, Portrait of Lady Dorothy Spencer, Countess of Sunderland, 1653

Samuel Cooper, Portrait of Lord Henry Howard, later 6th Duke of Norfolk, ca. 1663

Samuel Cooper is distinct among miniaturists for his enduring reputation as one of the greatest painters of his age.1Richard Graham, Cooper’s earliest biographer, wrote that Cooper’s “Talent was so extraordinary, that for the Honour of our Nation, it may without Vanity be affirmed he was (at least) equal to the most famous Italians; and that hardly any of his Predecessors has ever been able to show so much Perfection in so narrow a Compass” (emphasis original); Charles-Alphonse Dufresnoy, John Dryden, and Richard Graham, De Arte Graphica: The Art of Painting (London: Printed for J. Hepinstall for W. Rogers, 1695), 338–39. More recent appraisals of Cooper include Daphne Foskett et al., Samuel Cooper and his Contemporaries (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1974); Daphne Foskett, Samuel Cooper, 1607–1672 (London: Faber and Faber, 1974); and Bendor Grosvenor, ed., Warts and All: The Portrait Miniatures of Samuel Cooper (London: Philip Mould, 2013). Little is known of Cooper’s biography, but a large and consistently dated body of work from 1642 until his death in 1672 enables us to assess his legacy. Writer and art historian Horace Walpole proclaimed that “the anecdotes of Cooper’s life are few, [but] his works are his history.”2George Vertue and Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1849), 2:530. Cooper’s steady output is a testament to not only his work ethic but also his diplomacy and resilience amid one of the most turbulent periods in English history; his portraits were in high demand among rulers and Roundheads: A colloquial, initially derogatory term for members of the Parliamentary party during the English Civil War (1642–1651), led by Oliver Cromwell, who fought to overthrow the absolute monarchy of King Charles I. Roundheads were named for the men’s closely cropped hair, which was worn in opposition to the long wigs worn by adherents of the aristocratic Royalist party, reflecting the Roundheads’ objections to the Royalists’ pro-monarchy views. See also Parliamentary, Royalist. alike during the Civil War and beyond.

Born around 1608 to Richard Cowper and Barbara Hoskens, Samuel and his brother Alexander (1609–ca. 1660) were fostered as children by their uncle, the artist John Hoskins (ca. 1590–1665).3The spelling of names varied widely at this time. The names of Samuel Cooper’s parents are recorded here as they appear in the parish record of their marriage, “Hoskens” being a variant of the more widely-used spelling “Hoskins.” Cooper’s parents were unknown until Mary Edmond discovered the parish records for their marriage on September 1, 1607, at St. Nicholas Cole Abbey. Per Edmond, Alexander was baptized December 11, 1609. Samuel’s baptism was not recorded, but Edmond posited that he must have been the elder brother, likely born in late 1608, based on the date of his parents’ wedding and the inscription on his burial monument in St. Pancras Old Church. Mary Edmond, Limners and Picturemakers: New Light on the Lives of Miniaturists and Large-Scale Portrait-Painters Working in London in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (London: Walpole Society, 1980), 99. This early artistic exposure led to both brothers becoming miniaturists. Alexander was apprenticed to English miniaturist Peter Oliver (ca. 1594–1647), while Samuel joined their uncle’s studio, soon eclipsing Hoskins as his most celebrated student.4“He [Cooper] so far exceeded his Master, and Uncle, Mr. Hoskins, that he became jealous of him, and finding that the Court were better pleased with his Nephew’s Performances than with his, he took him in Partner with him; but still seeing Mr. Cooper’s Pictures were more relished, he was pleased to dismiss the Partnership, and so our Artist set up for himself, carrying most part of the Business of that time before him”; Roger de Piles, The Art of Painting (London: J. Nutt, 1706), 410. Both Hoskins and Oliver lived and worked in the central London parish of St. Ann Blackfriars, a hotbed of artistic talent.5The parish of St. Ann Blackfriars and the nearby “miniaturists’ parish” of St. Bride Fleet Street were well known for housing miniaturists and other artists, particularly those from Europe. See Edmond, Limners and Picturemakers, 100. Their most illustrious neighbor was the Flemish artist Sir Anthony Van Dyck (1599–1641), court painter to King Charles I.6John Murdoch, Seventeenth-Century English Miniatures in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), 115. Cooper had studied Van Dyck’s work and painted Van Dyck’s mistress Margaret Lemon early in his career.7Richard Graham wrote that he “derived the most considerable Advantages, from the Observations which he made on the Works of Van Dyck”; Graham, De Arte Graphica, 375. Cooper’s brilliant portrait of Van Dyck’s mistress Margaret Lemon wearing men’s clothing is now at the Fondation Custodia, Paris: Portrait of Margaret Lemon, ca. 1635–37, watercolor on vellum, 4 3/4 x 3 7/8 in. (12 x 9.8 cm), inv. 395, https://www.fondationcustodia.fr/Margaret-Lemon-1722. Cooper’s earlier miniatures exhibit some Van Dyckian influence, which lingered in his subsequent reputation as “Van Dyck in little.” However, by the 1640s, Cooper had come into his own style, distinguished by his bravura brushwork and the simplicity of his direct, astute representations. This artistic candor allegedly led Lord Protector Oliver Cromwell to request that Cooper paint him “warts and all.”8While this quotation is closely associated with Cooper’s legacy, it was likely intended for Lely, who was famous for flattering his sitters. Cooper’s portrait of Cromwell in the Buccleuch collection, featuring a prominent wart, aptly illustrates this exchange, perhaps explaining its link to Cooper. Laura Lunger Knoppers, Constructing Cromwell: Ceremony, Portrait and Print, 1645–1661 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 80.

Cooper likely lived in Continental Europe for several years, resurfacing in 1642 with a move to Covent Garden, in the West End of London.9“He spent several Years of his Life abroad, was personally acquainted with the greatest Men of France, Holland and his own Country, and by his Works more universally known in all the Parts of Christendom.” Graham, De Arte Graphica, 339. It is unknown exactly where Cooper traveled. Around this time, he married Christiana Turner (1623–1693).10The date of their marriage is unknown but likely occurred before 1643, when Cooper moved to King Street in Covent Garden. The Coopers moved in 1650 to a fashionable address on Henrietta Street, where they remained until Cooper’s death. Susannah-Penelope Rosse (English, ca. 1655–1700) took up residence at the same home shortly afterward, exemplifying the close ties between miniaturists of this era. Edmond, Limners and Picturemakers, 101–4. Exposure to Continental art seems to have imparted a cosmopolitan flair to both Cooper and his miniatures, most visible in the vibrant coloring that evokes the court portraits of Swiss enameller Jean Petitot (1607–1691). Cooper moved in intellectual circles with philosophers, antiquarians, and poets.11Some of Cooper’s most celebrated intimates included the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, the poet Samuel Butler, the antiquarian John Aubrey, and the diarist John Evelyn. Foskett, Samuel Cooper, 42–43. Epitomizing the courtly artist, fluent in several languages, and a talented lutenist, Cooper was described by Cosimo III de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, as “a tiny man, all wit and courtesy, as well housed as Lely, with his table covered with velvet.”12Daphne Foskett, Collecting Miniatures (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club, 1979), 95. Cosimo was keen to have his portrait painted by Cooper. See also Lorenzo Magalotti, Travels of Cosimo the Third, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Through England, During the Reign of King Charles the Second (1669) (London: J. Mawman, 1821), 166. Cooper was indeed paid handsomely for his work, especially after his 1663 appointment as limner: One who limns. See also limning. to King Charles II, enabling him to secure accommodations that rivaled those of the court’s preeminent portraitist, Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680), who succeeded Van Dyck in that role. In the 1660s, a typical miniature by Cooper cost thirty pounds.13Cosimo III griped, “[Cooper] gets paid thirty pounds each for [miniature portraits] and pretends to do you a great favour.” W. E. Knowles Middleton, Lorenzo Magalotti at the Court of Charles II: His Relazione d’Inghilterra of 1668 (Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1980), 150. The diarist Samuel Pepys discusses payment to Cooper for a portrait of his wife in his entry dated August 10, 1668: “He hath 30l [£30] for his work, and the chrystal [sic] and case and gold case comes to 8l-3s-4d [£8, 3s, 4d.], which I sent him this night that I might be out of his debt.” Robert Latham and William Matthews, eds., The Diary of Samuel Pepys (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 9:277. Lely charged the same amount for a full-scale oil portrait, suggesting that Cooper’s fees for miniatures were competitive with those of the foremost painters in Britain.14On Lely’s fees in the 1660s, see Mary Bryan H. Curd, Flemish and Dutch Artists in Early Modern England (London: Ashgate, 2010), 137.

Despite the era’s volatile politics, the demand for Cooper’s work endured, with one eager patron, Dorothy Osborne, promising her portrait “as soon as Mr. Cooper will vouchsafe to take the pains to draw it for you. I have made him twenty courtesys, and promised him £15 to persuade him.”15Osborne’s efforts to secure a portrait by Cooper for her lover Sir William Temple are documented in a letter dated June 13, 1654, published in Edward Abbott Parry, ed., The Letters of Dorothy Osborne to Sir William Temple, 1652–54 (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1901), 303. Cooper’s thriving career was cut short by his death in 1672 after a sudden illness. He was eulogized by the diarist Charles Beale: “Sunday May 5 [1672], the most famous limner of the world for a face died.”16The diary entries of Charles Beale (1631–1705), husband and studio assistant of the painter Mary Beale (1633–1699), are published in Vertue and Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England, 2:539.

Notes

-

Richard Graham, Cooper’s earliest biographer, wrote that Cooper’s “Talent was so extraordinary, that for the Honour of our Nation, it may without Vanity be affirmed he was (at least) equal to the most famous Italians; and that hardly any of his Predecessors has ever been able to show so much Perfection in so narrow a Compass” (emphasis original); Charles-Alphonse Dufresnoy, John Dryden, and Richard Graham, De Arte Graphica: The Art of Painting (London: Printed for J. Hepinstall for W. Rogers, 1695), 338–39. More recent appraisals of Cooper include Daphne Foskett et al., Samuel Cooper and his Contemporaries (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1974); Daphne Foskett, Samuel Cooper, 1607–1672 (London: Faber and Faber, 1974); and Bendor Grosvenor, ed., Warts and All: The Portrait Miniatures of Samuel Cooper (London: Philip Mould, 2013).

-

George Vertue and Horace Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1849), 2:530.

-

The spelling of names varied widely at this time. The names of Samuel Cooper’s parents are recorded here as they appear in the parish record of their marriage, “Hoskens” being a variant of the more widely-used spelling “Hoskins.” Cooper’s parents were unknown until Mary Edmond discovered the parish records for their marriage on September 1, 1607, at St. Nicholas Cole Abbey. Per Edmond, Alexander was baptized December 11, 1609. Samuel’s baptism was not recorded, but Edmond posited that he must have been the elder brother, likely born in late 1608, based on the date of his parents’ wedding and the inscription on his burial monument in St. Pancras Old Church. Mary Edmond, Limners and Picturemakers: New Light on the Lives of Miniaturists and Large-Scale Portrait-Painters Working in London in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (London: Walpole Society, 1980), 99.

-

“He [Cooper] so far exceeded his Master, and Uncle, Mr. Hoskins, that he became jealous of him, and finding that the Court were better pleased with his Nephew’s Performances than with his, he took him in Partner with him; but still seeing Mr. Cooper’s Pictures were more relished, he was pleased to dismiss the Partnership, and so our Artist set up for himself, carrying most part of the Business of that time before him”; Roger de Piles, The Art of Painting (London: J. Nutt, 1706), 410.

-

The parish of St. Ann Blackfriars and the nearby “miniaturists’ parish” of St. Bride Fleet Street were well known for housing miniaturists and other artists, particularly those from Europe. See Edmond, Limners and Picturemakers, 100.

-

John Murdoch, Seventeenth-Century English Miniatures in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1997), 115.

-

Richard Graham wrote that he “derived the most considerable Advantages, from the Observations which he made on the Works of Van Dyck”; Graham, De Arte Graphica, 375. Cooper’s brilliant portrait of Van Dyck’s mistress Margaret Lemon wearing men’s clothing is now at the Fondation Custodia, Paris: Portrait of Margaret Lemon, ca. 1635–37, watercolor on vellum, 4 3/4 x 3 7/8 in. (12 x 9.8 cm), inv. 395, https://www.fondationcustodia.fr/Margaret-Lemon-1722.

-

While this quotation is closely associated with Cooper’s legacy, it was likely intended for Lely, who was famous for flattering his sitters. Cooper’s portrait of Cromwell in the Buccleuch collection, featuring a prominent wart, aptly illustrates this exchange, perhaps explaining its link to Cooper. Laura Lunger Knoppers, Constructing Cromwell: Ceremony, Portrait and Print, 1645–1661 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 80.

-

“He spent several Years of his Life abroad, was personally acquainted with the greatest Men of France, Holland and his own Country, and by his Works more universally known in all the Parts of Christendom.” Graham, De Arte Graphica, 339. It is unknown exactly where Cooper traveled.

-

The date of their marriage is unknown but likely occurred before 1643, when Cooper moved to King Street in Covent Garden. The Coopers moved in 1650 to a fashionable address on Henrietta Street, where they remained until Cooper’s death. Susannah-Penelope Rosse (English, ca. 1655–1700) took up residence at the same home shortly afterward, exemplifying the close ties between miniaturists of this era. Edmond, Limners and Picturemakers, 101–4.

-

Some of Cooper’s most celebrated intimates included the philosopher Thomas Hobbes, the poet Samuel Butler, the antiquarian John Aubrey, and the diarist John Evelyn. Foskett, Samuel Cooper, 42–43.

-

Daphne Foskett, Collecting Miniatures (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club, 1979), 95. Cosimo was keen to have his portrait painted by Cooper. See also Lorenzo Magalotti, Travels of Cosimo the Third, Grand Duke of Tuscany, Through England, During the Reign of King Charles the Second (1669) (London: J. Mawman, 1821), 166.

-

Cosimo III griped, “[Cooper] gets paid thirty pounds each for [miniature portraits] and pretends to do you a great favour.” W. E. Knowles Middleton, Lorenzo Magalotti at the Court of Charles II: His Relazione d’Inghilterra of 1668 (Waterloo, Canada: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1980), 150. The diarist Samuel Pepys discusses payment to Cooper for a portrait of his wife in his entry dated August 10, 1668: “He hath 30l [£30] for his work, and the chrystal [sic] and case and gold case comes to 8l-3s-4d [£8, 3s, 4d.], which I sent him this night that I might be out of his debt.” Robert Latham and William Matthews, eds., The Diary of Samuel Pepys (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 9:277.

-

On Lely’s fees in the 1660s, see Mary Bryan H. Curd, Flemish and Dutch Artists in Early Modern England (London: Ashgate, 2010), 137.

-

Osborne’s efforts to secure a portrait by Cooper for her lover Sir William Temple are documented in a letter dated June 13, 1654, published in Edward Abbott Parry, ed., The Letters of Dorothy Osborne to Sir William Temple, 1652–54 (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1901), 303.

-

The diary entries of Charles Beale (1631–1705), husband and studio assistant of the painter Mary Beale (1633–1699), are published in Vertue and Walpole, Anecdotes of Painting in England, 2:539.

Richard Cosway (English, 1742–1821)

Works by This Artist

Richard Cosway, Portrait of a Woman, 1777

Richard Cosway, Portrait of Robert Bertie, 4th Duke of Ancaster and Kesteven, ca. 1779

Richard Cosway, Portrait of a Man, Probably William Nathan Wright Hewett, ca. 1780

Richard Cosway, Portrait of a Woman, 1787

Richard Cosway, Portrait of Honora Margaretta Lambart, the Countess Cavan, ca. 1789

Richard Cosway, Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1790-1795

Richard Cosway, Portrait of Lady Charlotte FitzGerald, later 21st Baroness de Ros, 1791

Richard Cosway, Portrait of Sir Robert Adair, 1792

Born in Devon as the son of a schoolmaster, Richard Cosway became one of the most influential and successful portrait miniature painters in England during the Georgian era. His family sent him to London in 1754, at the age of twelve, to study drawing and portraiture (both in oil and in miniature) under William Shipley (1715–1803), who had recently formed the Society for Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce.1The Society of Arts, as it was also known, attracted many talented students, including fellow miniaturist John Smart (1741–1811), who became Cosway’s professional rival. Cosway exhibited his work publicly throughout the 1760s, entering the newly formulated Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. Schools in 1769, first as a student, and then, by 1771, as an elected associate academician. He continued to exhibit his work annually at the Royal Academy from 1770 to 1787, 1798 to 1800, and in 1803 and 1806.2Stephen Lloyd, “Richard Cosway,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, last updated January 3, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6383.

In 1781, Cosway married Maria Hadfield (1760–1838), a talented musician and painter from Florence, Italy, who then settled in London with her new husband.3The Cosways had one daughter, Louisa Paolina Angelica Cosway (1790–1797), who died after contracting a sore throat. See Lloyd, “Richard Cosway.” They hosted salons in their studio and home, which became the place to see and be seen among the fashionable set. During this time, Cosway secured the patronage of the Prince of Wales (later King George IV) from 1780 to 1808. As the future king’s principal painter, Cosway also exerted his powerful influence on the royal family’s collecting habits, serving as their art advisor until 1811.4Cosway also assembled an impressive private collection of Old Master paintings and drawings. For more on this aspect of his career, see Stephen Lloyd, “Richard Cosway, R.A.: The Artist as Collector, Connoisseur and Virtuoso,” Apollo 138 (June 1991): 398–405. Cosway had other important aristocratic patrons as well, including William (Kitty), third Viscount Courtenay (1768–1835), whose portrait is in the Nelson-Atkins collection.5For more on Cosway’s patronage, see Lloyd, “Richard Cosway.”

Cosway was eccentric in behavior and dress, and his personality matched the bravura of his brushwork. His facility of line was unrivalled, as was his ability to showcase the natural translucence of his ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. supports through his use of transparent pigment: A dry coloring substance typically of mineral or organic origins until the nineteenth century, when they began to be artificially manufactured. Pigments were ground into powder form by the artist, their workshop assistants, or by the vendor they acquired the pigment from, before being mixed with a binder and liquid, such as water. Pigments vary in granulation and solubility.. Although his final years were filled with illness—he died on July 4, 1821—his dashing likenesses capture the sensuousness and frivolity of the era.

Notes

-

The Society of Arts, as it was also known, attracted many talented students, including fellow miniaturist John Smart (1741–1811), who became Cosway’s professional rival.

-

Stephen Lloyd, “Richard Cosway,” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, last updated January 3, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/6383.

-

The Cosways had one daughter, Louisa Paolina Angelica Cosway (1790–1797), who died after contracting a sore throat. See Lloyd, “Richard Cosway.”

-

Cosway also assembled an impressive private collection of Old Master paintings and drawings. For more on this aspect of his career, see Stephen Lloyd, “Richard Cosway, R.A.: The Artist as Collector, Connoisseur and Virtuoso,” Apollo 138 (June 1991): 398–405.

-

For more on Cosway’s patronage, see Lloyd, “Richard Cosway.”

Samuel Cotes (English, 1733–1818)

Works by This Artist

Samuel Cotes, Portrait of Miss Grosvenor, Probably Maria Deborah Grosvenor, 1770

Samuel Cotes, Portrait of Master Grosvenor, Probably Richard Grosvenor, 1770

Samuel Cotes, Portrait of a Woman, 1774

Samuel Cotes, Portrait of a Man, Probably John Whitelock, 1780

Samuel Cotes was the third son born to Robert Cotes (1693–1774), the former mayor of Galway, Ireland, and later an apothecary, and Elizabeth Lynn (1702–1776), daughter of the chief secretary of the Royal African Company, Francis Lynn (1671–1731).1Neil Jeffares, “Francis Cotes (1726–1770) and His Family,” British Art Journal 16, no. 3 (Winter 2015/2016): 68. Robert Cotes served as mayor from 1716 to 1717, at the ripe age of twenty-one. After the Protestant aldermen of the Irish House of Commons accused Cotes of failing to enforce anti-Catholic penal laws, Cotes was forced to leave his post and move to London, where he took up the profession of apothecary. Robert married Elizabeth in 1725; London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P69/KAT2/A/001/MS07889/003. Scholars previously believed Samuel Cotes’s year of birth to be 1734, but a recently discovered parish record has firmly established his date of birth as January 23, 1733.2Westminster Church of England Parish Registers, ref. SML/PR/3/4 part 2. Cotes intended to follow his father’s profession as an apothecary in London but abandoned this to pursue a career in fine art under his older brother Francis’s instruction.3H. C. G. Matthew and Brian Harrison, “Cotes, Samuel (1734–1818),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 13:570. For the entry on Samuel Cotes as a pastellist, see Neil Jeffares, “Cotes, Samuel,” Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800, online edition (Norwich: Unicorn Press, 2006), 1–2, http://www.pastellists.com/Articles/CotesS.pdf. Francis Cotes (English, 1726–1770) was celebrated for his pastel and crayon drawings as well as his large-scale oil paintings.4Introducing Francis Cotes, R.A. (1726–1770), ed. Alastair Smart (Nottingham: Nottingham University Art Gallery, 1971), 7.

Samuel and Francis were living at Cork Street, London, in 1763 while also exhibiting at the Society of Artists. In 1769, Samuel Cotes moved to 25 Percy Street, Rathbone Place, and began exhibiting at the newly created Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects..5He was one of the earliest exhibitors at the Royal Academy, contributing thirty-five portraits between 1769 and 1789. Joshua James Foster, British Miniature Painters and Their Works (London: Sampson Low and Marston, 1898), 62; Matthew and Harrison, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 13:571. His early work included enamel: Enamel miniatures originated in France before their introduction to the English court by enamellist Jean Petitot. Enamel was prized for its gloss and brilliant coloring—resembling the sheen and saturation of oil paintings—and its hardiness in contrast to the delicacy of light sensitive, water soluble miniatures painted with watercolor. Enamel miniatures were made by applying individual layers of vitreous pigment, essentially powdered glass, to a metal support, often copper but sometimes gold or silver. Each color required a separate firing in the kiln, beginning with the color that required the highest temperature; the more colors, the greater risk that the miniature would be damaged by the process. The technique was difficult to master, even by skilled practitioners, leading to its increased cost in contrast with watercolor miniatures. miniatures, a craft he may have learned from Nathaniel Hone (Irish, 1718–1784) or possibly Jean-André Rouquet (Swiss, active in England and France, 1701–1758).6Cotes’s enamels display the bright colors he intended for his palette, in contrast to his watercolor portraits that have faded from light exposure over time. Rouquet was active in London from around 1722 to 1752.