In 1961, John W. and Martha Jane Starr described their collecting of portrait miniatures as an “Oklahoma cyclone, moving slowly forward and dipping down occasionally to snatch a new treasure.”1An abridged version of this essay appears in Bernd Pappe and Juliane Schmieglitz-Otten, eds., Portrait Miniatures: Artists, Functions, Techniques and Collections (Petersberg: Michael Imhof, 2022), 231–41. I am grateful to Bernd Pappe, Juliane Schmieglitz-Otten, and the Tansey Miniatures Foundation for the opportunity to publish and present my initial findings on the Starrs and their collecting. For the quote from the Starrs, see Martha Jane and John W. Starr, “Collecting Portrait Miniatures,” Antiques (November 1961): 437–41. This metaphor is a fitting one for the Phillips Petroleum heiress, who was born Martha Jane Phillips in 1906 in what was then known as the Oklahoma territory, in the south-central United States. She attended finishing school in Boston and married John Wilbur Starr, an insurance executive, in 1929. The couple moved to Kansas City two years later and became leaders in the city’s civic and social life (Fig. 1). Mrs. Starr was raised with the ethos, passed down from her father Lee Eldas Phillips (1876–1944), co-founder of Phillips Petroleum, that “whatever talents we have ought to be used to make the world better . . . and to make the human family happier.”2“The Martha Jane Phillips Starr Legacy,” Harbor Light (November 2017): 1. This tenet shaped John W. and Martha Jane Phillips Starr as curious, discerning, and civic-minded collectors.

Martha Jane grew up surrounded by collectors of various sorts, many of a philanthropic bent. They ranged from her brother, who had an important collection of Colt rifles; to her uncle Frank Phillips, whose interest in the art of the American West formed the nucleus of his museum, Woolaroc; to her uncle and aunt Waite and Genevieve Phillips, whose home and collection became the Philbrook Museum of Art in Tulsa.3The development of Woolaroc and the Philbrook Museum is related in Michael Wallis, Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014). Martha Jane kept a notebook in which she describes a portrait of a lady purchased in Italy in 1922, when she was sixteen, as “the first of [her] collection.”4Notebook, undated, box 22, folder 10, Martha Jane Starr Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Her second significant acquisition, a portrait of a woman with two children, was given to her and John as a wedding gift by her Aunt Genevieve, perhaps passing the collecting torch to her niece. The sentimental nature of this gift is a theme that runs throughout the Starrs’ early acquisitions, with many miniatures purchased as gifts for holidays, birthdays, and anniversaries.5Inventory, undated (1930s), box 22, folder 9, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

Beyond some gifts from family and friends and scattered souvenirs purchased in the early years of their marriage, the Starrs began actively acquiring miniatures in about 1936. They collected decorative miniatures with descriptions such as “Lady in green,” “Lady with pink hat,” “Foreign looking lady,” and “Italian girl with fruit basket,” or what Mrs. Starr called “small pictures of pretty court ladies,” from antique stores in Kansas City, Chicago, and St. Louis; Art Trading Co. in New York; and dealer Daniel Mackie on a trip to London in 1936.6Inventory, undated (1930s). In 1937, Mrs. Starr made her first independent sortie as a collector, using her growing network to connect with the director of the Art Institute of Chicago in search of sources for miniatures—including “an authentic . . . Isabey,” which the Starrs eventually did acquire (Fig. 2).7Robert Harshe to Martha Jane Starr, November 1, 1937, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

Sometime in 1937, the Starrs made contact with Harry Wehle, a curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, which led to a watershed moment in their collecting. The Starrs themselves pinpointed when their sentimental pastime transitioned from a hobby to a serious endeavor. In 1958, John W. Starr told the Kansas City Star:

It was in 1937 that we were challenged, so to speak, by a visit to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. My wife and I through the years had accumulated 40 or 50 miniatures, and we were quite proud of them. So we took them to the Metropolitan and asked if they were of any significance. We were told, in a very nice way, that we had nothing.8“Tiny Art Gems to Be Displayed at Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Star, December 11, 1958, 2.

Rather than giving up collecting altogether, the Starrs resolved to begin anew. Most of that first collection was dispersed on Wehle’s advice, and the couple slowly rebuilt, taking a more strategic approach, although they retained some of their taste for decorative miniatures—providing, they attested, that “they were of historical value.”9“Tiny Art Gems.” A portrait of George IV by Paul Fischer is the only identifiable work from that initial collection; it is listed as a Christmas gift from Mrs. Starr’s mother, Leonora Carr Phillips (1876–1966), purchased in 1937. In the Starrs’ preliminary inventory, it is marked with an asterisk as one they planned to keep (Fig. 3).10Inventory, undated (1930s).

The Starrs continued to correspond and meet with curators. In 1940, Mrs. Starr wrote to Maurice Block, curator of the Huntington Library in San Marino, California, thanking him for sharing his thoughts on their collection and for introducing her to a conservator, a Mr. Bachmann, who “found some interesting material and dates and kept a number for him to clean and repair.” She also requested that he share their name with “anyone who has early miniatures for sale that the gallery is not interested in,” as, she said, “that is the nicest way of acquiring new pieces.”11Martha Jane Starr to Maurice Block, January 16, 1940, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

In 1940, on the advice of Harry Wehle, Mrs. Starr contacted Edward Greene in Cleveland, the most prominent collector of portrait miniatures in the United States at that time. She wrote, “I have been interested in miniatures for many years and have learned the hard way my error. . . . [In] the last few years I have acquired a library on miniatures—and a few choice pieces.” She mentions having seen miniatures at the Huntington and in J. P Morgan’s collection (through which we know she later acquired a miniature by Samuel Cooper) and further adds, “my few important ones are English”—“by [Andrew] Plimer, [Ozias] Humphrey [sic], and [Richard] Cosway.”12Martha Jane Starr to Edward Greene (draft), September 7, 1940, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

By the early 1940s, she was also meeting with curators at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, which had opened in 1933. The museum’s first director, Paul Gardner, was eager to cultivate local collectors and had begun advising the Starrs. Gardner provided letters of introduction to facilitate their visits to various private and public collections.13For example, in a letter to William G. Constable, curator of painting at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mrs. Starr noted that she was “indebted to Mr. Paul Gardner for his letter to you.” Martha Jane Starr to W. G. Constable, November 6, 1942, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. During the Second World War, however, the Starrs’ collecting came to a halt, like that of so many others. While Mr. Starr was serving in the Pacific theater, Mrs. Starr devoted herself to philanthropic endeavors, volunteering for the Red Cross beginning in 1942 before being appointed Chair of the Red Cross Nurse’s Aide program through 1946.14David J. Trowbridge, Katy Anielak, and Clio Admin, “Starr Women’s Hall of Fame, University of Missouri-Kansas City,” Clio: Your Guide to History, November 16, 2021, https://www.theclio.com/entry/141401.

The Starrs returned to their pursuit of miniatures with a slew of letters from Mrs. Starr in September and October of 1947 to curators in St. Louis, Chicago, Cleveland, and New York.15Group of letters, September 12, 1947–February 1948, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. In February 1948, she wrote to arrange another visit with Maurice Block of the Huntington, stating unequivocally, “Mr. Starr and I are resuming our hobby of collecting and are deep in research of identifying our collection.”16Martha Jane Starr to Maurice Block, February 16, 1948, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Mrs. Starr’s method of befriending curators seems to have been effective in at least one instance, as she began a lengthy and productive correspondence with Louise Burchfield, a curator at the Cleveland Museum of Art.17As well as being an assiduous correspondent, Mrs. Starr had a unique method for ingratiating herself into the good graces of various curators. There are several notes in the Starr archives thanking Mrs. Starr for sending large boxes of caramels and chocolates that were apparently quite delicious. For example: Catherine Filsinger, assistant curator, City Museum of Saint Louis, to Martha Jane Starr, September 12, 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection; Louise Burchfield, Cleveland Museum of Art, to Martha Jane Starr, perhaps December 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

In the spring of 1948, Mrs. Starr’s trail of breadcrumbs paid off handsomely with a letter from Hans Huth, a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, who shared an offer the museum had received from Berry-Hill Galleries of a miniatures collection “formed in about 1913 by the late Lord Duveen.”18Hans Huth to Martha Jane Starr, March 17, 1948. Mrs. Starr replied on April 3, 1948: “Your letter of March 17, 1984, was received with much interest and I have been having most satisfactory correspondence with Berry-Hill regarding the miniature collection. . . . I am looking forward to seeing them first hand. . . . Mr. Starr and I are anticipating a detailed examination of the pieces. . . . It was most thoughtful of you to refer the name to me and it may result in some additions to our collection.” Mr. Huth later wrote to Mrs. Starr on October 22, 1948: “I am sorry I was not in Chicago when you happened to come in. I am glad you have made some good purchases and I hope to see you next time you are in town.” All three letters, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Today, of the seventeenth-century miniatures illustrated in an undated album in the Duveen archive at the Getty, four from consecutive pages—by Samuel Cooper, Nicholas Dixon, Thomas Flatman, and Peter Crosse (Fig. 4)—are now in the Nelson-Atkins collection.19Duveen Brothers, Miniatures, undated, Special Collections, series I.A., box 15, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, http://hdl.handle.net/10020/2007d1_d0009. These acquisitions helped the Starrs gain confidence in their collecting, but they had learned enough to know that they needed expert support. Mrs. Starr contacted several curators seeking assistance “in my study and collection hobby of portrait miniatures,” as she wrote. “I have come to the stage of needing more counsel and assistance in compiling a catalogue of my collection and further research on this subject.”20To a Mrs. Burrough (presumably Louise Burroughs, with whom Mrs. Starr was a longtime correspondent), October 13, 1947: “Your name was given me by Mr. Paul Gardner, director of the Wm. Rockhill Nelson Art Gallery here in Kansas City, as a person who might be able to assist me in my study and collection hobby of portrait miniatures. I have been collecting for 20 years and after the usual trial and error method now have a small but authentic collection of 17th, 18th, and 19th century miniatures. On several occasions when I have been in New York City, Mr. Wehle has been gracious in seeing my group and advising with me, but now I have come to the stage of needing more counsel and assistance in compiling a catalogue of my collection and further research on this subject”; Martha Jane Starr to Mrs. Burroughs, October 13, 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. To Megrick Rogers, a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, Mrs. Starr wrote, “Mr. Paul Gardner . . . gave me your name as a person who might help me with my study, research, and collecting of portrait miniatures. This has been my hobby for twenty years, and I am very eager to find an assistant to help compile information I already have and guide me in furthering this work”; Martha Jane Starr to Megrick Rogers, October 13, 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. She wrote to Mr. Greene on the same day, asking about the possibility of viewing his collection in Cleveland; Martha Jane Starr to Edward Greene, October 13, 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. It would be twenty-four years before a preliminary catalogue would be published by the Nelson-Atkins.21Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971).

Letters exchanged with curators in the spring of 1949 show the Starrs strategizing for an upcoming trip that would be a veritable “greatest hits” tour of miniatures collections abroad. These included, in England, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Wallace Collection, the Buccleuch Collection, and dealers Sidney Hand and S. J. Phillips, from whom we know the Starrs purchased miniatures.22Wehle wrote to Mrs. Starr with “a review of the principal [collections of miniatures].” Harold Wehle to Martha Jane Starr, March 18, 1948, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection. In France, the Starrs visited the Louvre, the Musée Jacquemart-André, and the dealer Leo Schidlof, and in the Netherlands the collector Frits Lugt, based in The Hague.23In her reply to Wehle at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mrs. Starr wrote, “Many thanks for your help and interest. The Starrs like to remember that you were the person directly responsible for our serious interest in collecting and research on historical portrait miniatures.” Martha Jane Starr to Harry Wehle, April 16, 1949, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Thus followed a deluge of letters to Graham Reynolds (V&A), Lugt, Carl Winter (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge), and the Duke of Buccleuch.24“We are most eager to be guided to the proper persons as possible agents [in England], from whom we can develop this program. The sources we know are limited, so we are anxious for your ideas. . . . We hope to visit the famous collections in England before too many years and in the meantime we want to do research on our own. Perhaps you can give us suggestions about the following: How to best authentic[ate] our present group of miniatures; Find reliable sources for further additions of miniatures; Sources for finding new additions for our library; Entrée to the famous collections abroad when we do come over; Names of private collectors and collections in London; Catalogu[e]rs of ‘specific’ collections.” Martha Jane Starr to Graham Reynolds, April 10, 1949, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Letters jetted in and out of the US embassies in England, Belgium, France, and the Netherlands on behalf of the Starrs, facilitated by their friend and neighbor, Senator James Kem (R-MO), demonstrating how the couple’s talent for relentless networking played a vital role in the development of their collection.25Group of letters, 1949, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

The 1949 trip was a grand success. Mrs. Starr wrote triumphantly to Wehle: “The Starrs definitely saw all the portrait miniatures that their minds could hold.” She made it clear that the primary aim of the trip, beyond sightseeing, was “the opportunity of seeing miniatures, and finding leads whereby I could add new portraits to our own collection.”26Martha Jane Starr to Harold Wehle, October 7, 1949, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. After visiting every collection they could, the Starrs started acquiring more portrait miniatures. By this time, the Starrs had narrowed their focus to seventeenth- and eighteenth-century English miniatures, with a particular interest in John Smart (1741–1811), Cosway, and George Engleheart (1750–1829), though they would later purchase some continental and American miniatures to create a more representative collection.

Sadly, we have no knowledge of any existing receipts from the twenty purchases made on this trip, but a letter inviting the intrepid collectors to exhibit some of their newest miniatures at the Met in 1950 suggests some of these acquisitions.27Josephine Allen to Martha Jane Starr, September 8, 1953, curatorial file for “Four Centuries of Miniature Painting–1950,” European Paintings Department, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. In addition to the group of Duveen miniatures, the Starrs’ loans to the Met included miniatures by Charles Boit and Bernard Lens.28These loans are listed in a pamphlet printed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and digitized by the Met’s Watson Library: Four Centuries of Miniature Painting (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1950), https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll10/id/1175. The museum also exhibited Jean Petitot’s Portrait of Marie-Therese, which the Starrs later sold.29Catalogue of Fine Portrait Miniatures (London: Sotheby, March 31, 1949), lot 25.

By this time, in addition to their wide correspondence with museum experts, dealers, and gallerists, the Starrs were also in communication with other collectors. The eccentric US collector and later dealer Edward Grosvenor Paine wrote to Mrs. Starr in late 1948 through a mutual friend, Betty Hogg, as a fellow “lost soul to the cause” of miniatures. He introduced himself and his collection and offered in his “probing abroad [to] uncover anything that would help you complete your collection.”30Edward Grosvenor Paine to Martha Jane Starr, December 30, 1948, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Hogg served as an agent in the UK to both Paine and the Starrs. She assisted Mrs. Starr in purchasing a group of miniatures in a March 31, 1949, sale, including two by Smart (Portrait of Charles Stewart, 7th Earl of Traquair, ca. 1790 and Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1780) that survived all future housecleanings of the Starr collection.31Catalogue of Fine Portrait Miniatures (London: Sotheby, March 31, 1949), lots 48 and 60; group of letters between Martha Jane Starr and Betty Hogg, n.d., box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. The letters between Hogg and Mrs. Starr also mention Elsie Kehoe, who served as both advisor and competitor to the Starrs. They purchased eighteen miniatures from her 1950 sale, fitting their typical pattern of acquiring large groups at auction.32Catalogue of Objects of Vertu, Fine Watches and Portrait Miniatures, Including the Property of Mrs. W. D. Dickson; the Property of Mrs. Kehoe (London: Sotheby, June 15, 1950), lots 126, 131, 135–137, 141, 153, 158, 161, 163–64, 168, 172, 174–75. Several of the eighteen miniatures were grouped together in a single lot: 158, 164, and 175 each contained two miniatures.

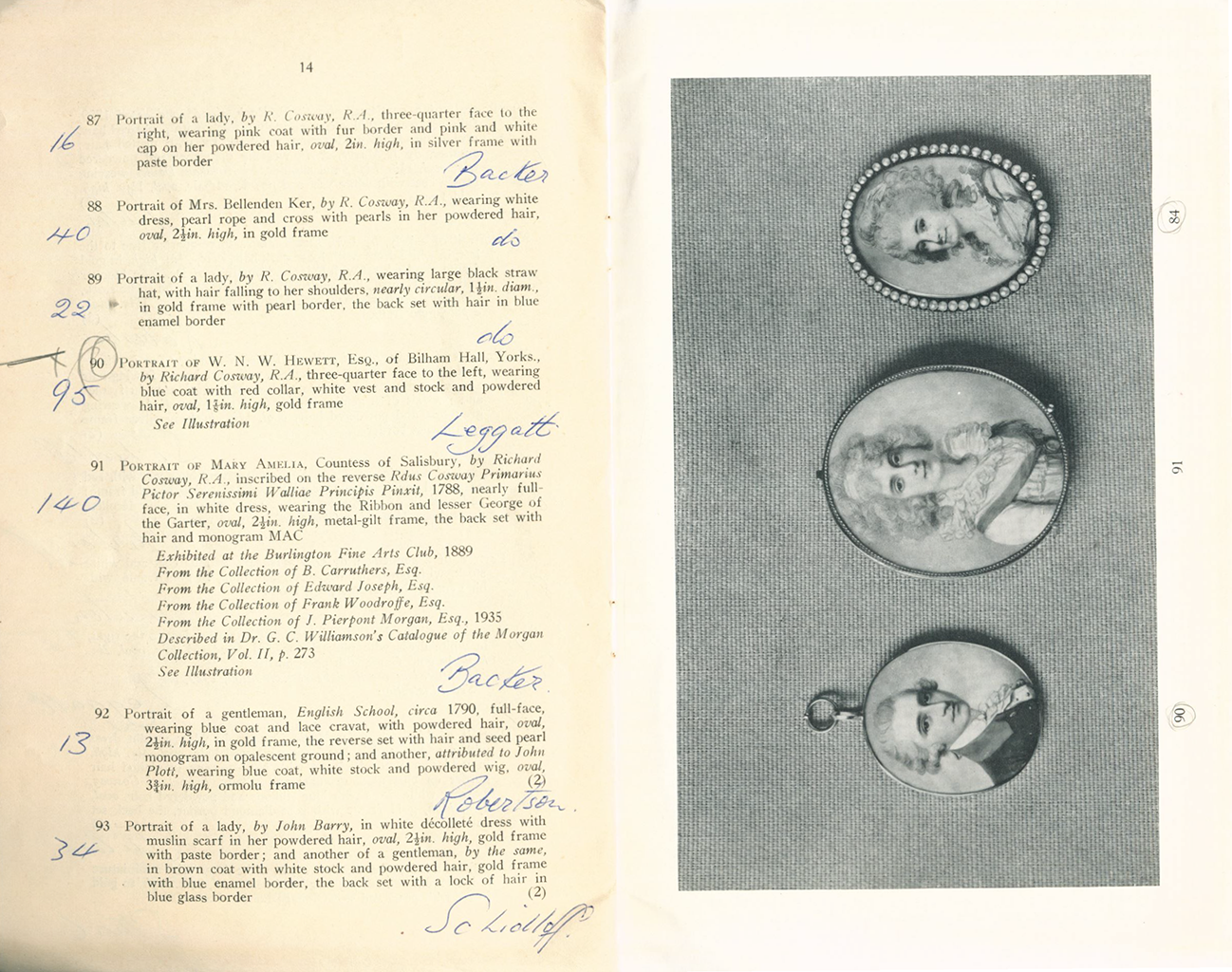

A large group of sales catalogues pertaining to portrait miniatures at the Miller Nichols Library at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) provides further insight on the purchasing habits of the Starrs, who did not otherwise leave behind a system of receipts or consistent purchase records.33Maggie Keenan took on the tremendous task of scanning these UMKC catalogues and painstakingly documenting the various sale records. UMKC was the selected repository of the Starrs’ archives after the passing of Mrs. Starr, and it logically followed that the Starrs’ sales catalogues, too, were left to the library. While the catalogues do not contain bookplates, and their prior ownership was not logged by the library, annotations in the catalogues match the Starrs’ handwriting and align with known purchases made by the Starrs—often illustrated or otherwise clearly identifiable by a circled lot number or check mark beside them (Fig. 5). A thorough study of the Starr auction records shows that the Starrs also frequently worked with the dealers Leggat Bros., also called Leggatt & Co., as a source for purchases of many portrait miniatures. In certain cases, the Starrs bought directly from Leggatt & Co. after they obtained works through auction or private ownership. In many more instances, however, when the Starrs were not able to travel to London, Leggatt served as purchasing agents to buy miniatures at auction that the Starrs were keen to acquire.34See correspondence between Betty Hogg and Martha Jane Starr, May 15 and June 3, 1950, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Betty Hogg wrote to Mrs. Starr on May 15, 1950, regarding her meeting with a “young Mr. Leggatt” and further conversations with a mutual friend, who assured her that the Starrs would be in good hands. In Mrs. Starr’s reply, dated June 3, 1950, she thanked Betty Hogg for connecting them with the Leggatts, writing, “Your Man Mr. L. [Leggatt] has been doing a nice job for us and we have bought at auction several items. Just a week ago we acquired 10 more! So we definitely thank you for your help in getting catalogues . . . and Mr. L. has been great.” The auction catalogues, in which Leggatt is frequently listed as the purchaser, show that the Starrs’ most active years of collecting miniatures were between the mid-1940s and 1958, with a high number of purchases between 1949 and 1952. In 1949 and 1950, they bought multiple miniatures from at least six sales per year.

In September 1953, John Smart came to the fore of the Starrs’ collecting efforts, beginning with a letter from Josephine Allen, an assistant curator at the Met, forwarding a request from Arthur Jaffé for information on any known Smart miniatures, as he was hard at work on his unrealized catalogue raisonné.35Josephine Allen, associate curator, Department of Paintings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote to Martha Jane Starr on September 8, 1953, “Don’t I remember that you have some very nice Smart miniatures?” Josephine Allen to Martha Jane Starr, September 8, 1953, curatorial file for John Smart, European Paintings department, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. It seems likely that Mrs. Starr began exchanging letters with Jaffé soon afterward. In 1953–54 she wrote to several experts in search of “a fine miniature,” “a real special gift” to commemorate her twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. Specifically, she sought a self-portrait by Smart, beginning a more than thirty-year search by the Starrs.36On August 18, 1954, Mrs. Starr wrote to Louise Burchfield: “Not long ago I wrote to Mr. Jaffé regarding help in finding a fine miniature for our October anniversary making Mr. Starr and I twenty-five years together. He had no leads on Hilliards or Olivers but did mention that word had come from you regarding a self portrait of Mr. Smart and that you could probably give us information.” Martha Jane Starr to Louise Burchfield, August 18, 1954, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. The spectacular new acquisition, a 1793 self-portrait by Smart, will be published in a catalogue entry in spring 2025, following conservation treatment and new photography. While they did not live to see a self-portrait join their collection, their descendants finally made this long-sought acquisition possible in the spring of 2024 (Fig. 6). It is well documented that Smart became their favorite artist quite soon after they began collecting, but we do not know when they decided to focus on the singular goal of acquiring a signed and dated miniature for each year of Smart’s career. It is clear, however, that by 1953 they had set their sights on this goal, visiting the UK specifically to acquire miniatures by Smart and to meet with Jaffé, Graham Reynolds, and Carl Winter about the artist.37Louise Burchfield to Martha Jane Starr, September 9, 1953, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Burchfield wrote, “I had such glowing letters from Mr. Reynolds and Mr. Winter telling how much they enjoyed their visits with you and Mr. Starr. And Mr. Winter spoke especially about the amazingly fine collection you have gathered together.”

The Starrs also correspondeded with Winter about their intentions to acquire earlier miniatures. A letter from Winter warmly (and perhaps a bit enviously) congratulated them on their presumed acquisition of Nicholas Hilliard’s portrait of George Clifford, Third Earl of Cumberland in 1955 (Fig. 7).

If you bought Lot 74 you have one of the greatest treasures of miniature painting. It ought to be at Windsor Castle . . . or in one of our national museums; but if none can or could afford it, and if it goes out of England, there are no hands in which I should so soon wish to think of it as in yours.”38Carl Winter to Martha Jane Starr, October 11, 1955, box 22, folder 9, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

The Hillard remains a jewel of the collection, not least because Clifford wears a spectacular suit of armor now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.39Made under the direction of Jacob Halder, Armor Garniture of George Clifford (1558–1605), Third Earl of Cumberland, 1586, steel, gold, leather, textile, 69 1/2 in. (176.5 cm) high, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Munsey Fund, 1932, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/23939. The purchase of George Clifford is very well documented; indeed, through this online catalogue project the Nelson-Atkins has been able to track its provenance by descent from the original owner. Mrs. Starr remarked, “We knew it was an important piece, by Nicholas Hilliard. But we didn’t know, when we sent in our bid, that we were bidding against the Metropolitan Museum.”40“Tiny Art Gems.”

Having made this crowning acquisition, the Starrs determined that the bulk of their collection should be preserved for posterity at their hometown museum. This choice to bequeath their “pets,” as Mrs. Starr called them, to the Nelson-Atkins, was not an idle one borne of proximity, but a relationship carefully cultivated over two decades by its first two directors, Paul Gardner and Laurence Sickman. Mrs. Starr acknowledged their help with introductions to various private and public collections of miniatures across the United States as well as suggestions of “further sources for us to gain information and additions to our library and portrait collections.”41Martha Jane Starr to Graham Reynolds, April 10, 1949, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection. As conversations with the Nelson-Atkins became official, and a target date, 1958, was selected for their gift, the Starrs’ collecting strategy rapidly veered from one developed largely out of personal interest to one with a strategic goal of gifting the museum with an encyclopedic collection of portrait miniatures. While their purchases after 1951 had dwindled to between one and two auctions per year, in 1957, they purchased groups of miniatures from at least ten individual auctions and participated in a further seven auctions in 1958, with a focus on building their holdings of continental miniatures and adding to their groupings of British and American portrait miniatures.

The initial 1958 gift of 199 miniatures, the bulk of the Starrs’ collection at that time, was timed to coincide with the twenty-fifth anniversary of the founding of the museum.42Jan Dickerson, “Rare Gifts by Kansas Citians, New Purchases and Loans in Nelson Gallery Exhibit,” Kansas City Star, December 7, 1958, 109. There was also much fanfare at the later opening, in 1963, of a twelve-sided jewel box of a gallery designed specifically to house the miniatures (Fig. 8). “We wanted to share [our collection] with others, and this seemed a fitting way,” said Mr. Starr at the time. “But this does not mean we are going to stop collecting miniatures. We have retained the right to add to the collection, with the permission of the trustees. And we can take away pieces, if we substitute better ones.”43“Tiny Art Gems.” Indeed, a wealth of later documentation in the Nelson-Atkins archives shows that the Starrs frequently swapped miniatures in and out years after the original gift.44Among many examples are Ross Taggart to Laurence Sickman, October 21, 1971, RG 98-box 08, folder 4, Archives, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; Ross Taggart to Mr. and Mrs. John W. Starr, November 11, 1971, box 9, folder 3, Martha Jane Starr Collection; John W. Starr to Laurence Sickman, September 14, 1966, box 9, folder 3, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

Following the 1958 gift, the Starrs continued to pursue their Smart project. They had first encountered the miniatures specialist and collector Daphne Foskett around 1961, connected through Edward Paine, who was helping Foskett access Smart miniatures in the United States. Paine wrote to Foskett that year to urge patience in waiting for a communication from Mrs. Starr, and his description of her is utterly characteristic: “Mrs. Starr is a very busy woman, with her favorite charities, church, Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts, museum, birth control plans . . . and too many others to mention, but eventually she will get around to it.”45Edward Grosvenor Paine to Daphne Foskett, September 26, 1961, folder 1, Foskett. The Starrs, especially Mrs. Starr, were highly involved and instrumental for decades in their support for urban beautification, including the establishment of several fountains and an ongoing butterfly exhibit at the Martha Jane Phillips Starr Conservatory at Powell Gardens in Kingsville, Missouri. Mrs. Starr’s significant work at the University of Missouri-Kansas City was tied to her long affiliation with Planned Parenthood, beginning in 1947. She endowed a chair in human reproduction and established scholarships to encourage women to pursue graduate studies. The forward-thinking Mrs. Starr was a lifelong champion of family planning and birth control advocacy.46Mara Rose Williams, “Shaping the Civic Landscape: Martha Jane Starr, Education, Scouting and the Arts,” Kansas City Star, December 8, 2011, 19. Indeed, despite her many crusades and commitments, Mrs. Starr did reply to Foskett. They met in person in 1963 and became lifelong correspondents and friends.47I am grateful to Daphne Foskett’s daughter, Helen Godfrey, for her generosity in welcoming me to her home in Edinburgh and sharing recollections about her mother’s writing, collecting, and their friendship with the Starrs.

In 1964, the Starrs were trying to complete their collection of Smarts, assisted by both Foskett and Sickman (who had become director of the Nelson-Atkins in 1953), in searching out auctions and contacting collectors far and wide.48Martha Jane Starr to Mrs. Burton Jones, undated (likely November 1954); Laurence Sickman to Mrs. Burton Jones, November 18, 1964, both letters in the registration files, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Regarding their inquiry into the whereabouts of Smart miniatures, see also Daphne Foskett to John W. Starr, October 7, 1964, registration files, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. In advance of their planned gift to the museum of fifty-one consecutively dated miniatures by Smart,49This was in addition to the thirteen miniatures and works on paper by Smart that the Starrs donated with their initial gift in 1958, followed by a further two Smart miniatures in later gifts in 1971 and 1973. In 2018, 2023, and 2024, generous gifts from the Starr family enabled the Nelson-Atkins to acquire three more miniatures by Smart, including a self-portrait. the Starrs worked closely with curator Ross Taggart to plan an exhibition celebrating Smart’s life and work, featuring not only their own collection but also more than thirty loans from public and private collections, including Smart’s self-portrait from the V&A.50For example, a group of letters from Ross Taggart, August 1965, registration files, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The seventy Smart miniatures at the Nelson-Atkins include a signed and dated miniature for each year of Smart’s career, from 1760 to 1811. On the Starrs’ request, Daphne Foskett flew out to deliver a lecture at the opening in December 1965.51“Painter [sic] of Miniatures to Attend Show Here,” Kansas City Star, November 25, 1965, 10; Donald Hoffman, “400 at Benefit for Gallery—U.M.K.C.—The John W. Starrs Present Their Collection of John Smart Miniatures,” Kansas City Star, December 10, 1965, 3. In 1972, most of the Starrs’ collection was exhibited at the Royal Ontario Museum, which now has several Smarts of its own. “Starr Miniatures,” Toronto Globe and Mail, December 9, 1972.

The Starrs turned their focus at last to their long-held goal of publishing a catalogue of the collection, first accomplished by Ross Taggart in 1971. To their delight, Graham Reynolds wrote the introduction to the book.52Taggart, Starr Collection of Miniatures, 6–8. The Starrs continued to be involved in the assembly of the collection at the Nelson-Atkins as late as 1974, as shown in a letter Taggart wrote to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, attempting to fulfill the Starrs’ dream to acquire a self-portrait by Smart as the crowning glory of their collection.53Memo from Ross Taggart to Laurence Sickman, June 10, 1974, RG 98-Box 08, Folder 5, Archives, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The MFA politely rebuffed the Starrs’ suggestion to exchange a self-portrait by Edward Greene Malbone for their Smart self-portrait, despite other Starr miniatures Taggart offered to sweeten the deal.54Merrill C. Rueppel to Laurence Sickman, January 3, 1975; Sickman to Martha Jane Starr, January 8, 1975; Sickman to Rueppel, January 8, 1975. All three letters, RG 98-Box 08, Senior Curator Subject Files, folder 5, Starr Miniature Collection, 1971–1983, Archives, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Their persistence is revealed by a further exchange five years later, with Taggart again asking to purchase the MFA’s Smart self-portrait for the Nelson-Atkins, which the Boston museum was understandably only amenable to offering as a short-term loan.55Ross Taggart to John Walsh, October 8, 1981; Walsh to Taggart, October 15, 1981; Taggart to Martha Jane Starr, October 23, 1981. All three letters, RG 98-Box 08, Senior Curator Subject Files, folder 5, Starr Miniature Collection, 1971–1983, Archives, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

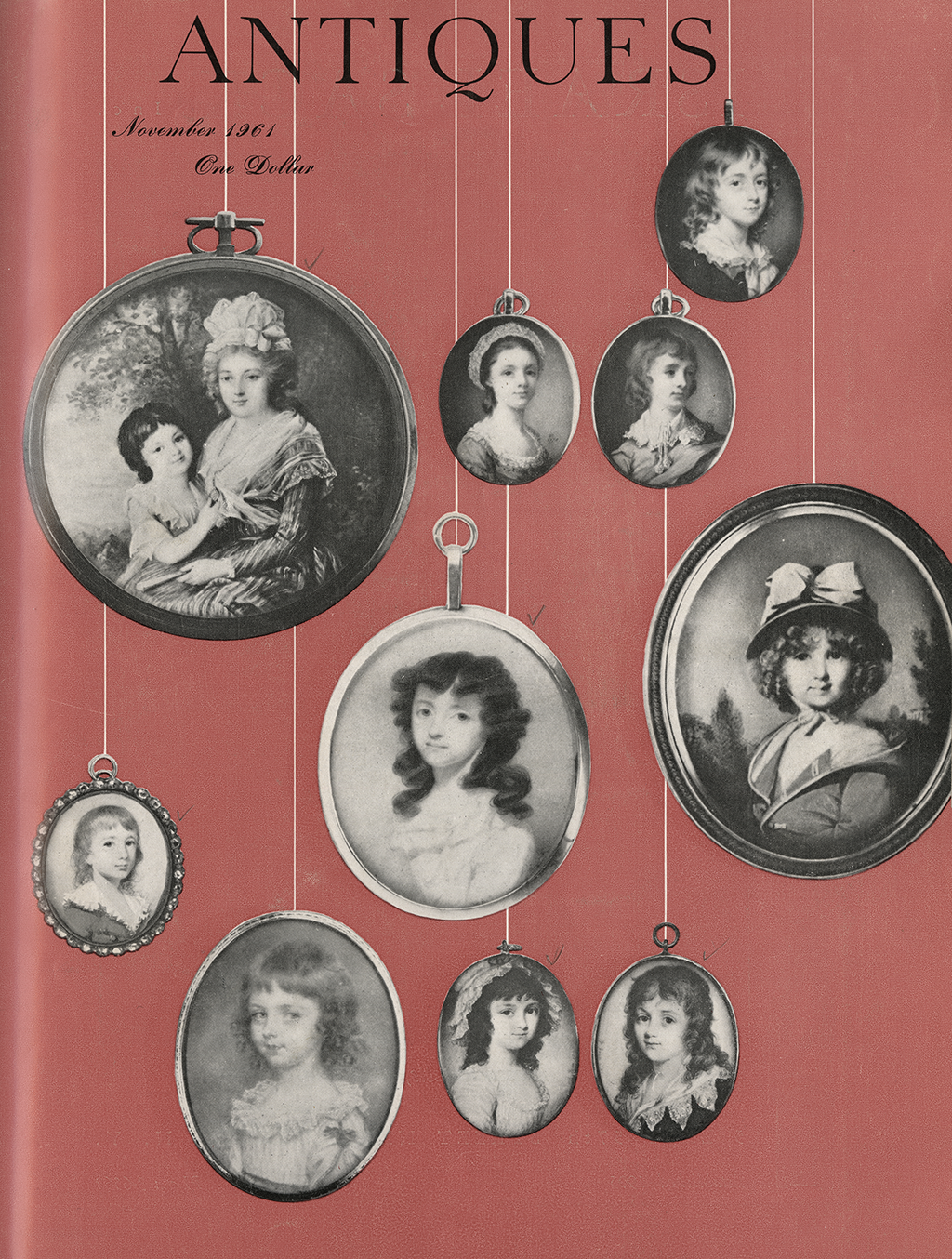

The Starrs were later honored in 1992, after the collection was reinstalled in a new gallery (Fig. 9). That year, they donated a group of memorabilia related to Smart and an American portrait miniature.56Unknown, Portrait of a Man, ca. 1820, 2 5/8 x 2 in. (6.7 x 5.1 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John W. Starr through the Starr Foundation, Inc. The Smart grouping includes a sealing wax impression of John Smart (https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/31539/portrait-of-john-smart, R92-2) after the medal by Joachim Smith and John Kirk (https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/23795/portrait-medal-of-john-smart, 2018.10), as well as legal and financial paperwork pertaining to John Smart’s estate; letters written between Smart’s children and the artist Robert Smirke (1752–1845) regarding a gift of a portrait of their father; and a diary kept by Smart’s son John James Smart. These documents are preserved in the Nelson-Atkins archives. They also bequeathed their substantial library of books on miniatures to the Spencer Art Reference Library at the Nelson-Atkins, as at that point they had “retired” from collecting to focus on Mrs. Starr’s charitable endeavors.57According to a pamphlet printed to commemorate the 1992 reinstallation of the Starr miniatures collection, the Starrs’ books on miniatures were placed on deposit at the Nelson-Atkins that year; they are now in the permanent collection of the Spencer Art Reference Library. “The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures,” pamphlet (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1992), registration files, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Mr. Starr reflected on their thoughtful and quite personal approach to collecting: “In sorting over and building our collection, we have eliminated miniatures that others might prize. We did not concentrate on quantity, but on a good representation of key artists.”58“Tiny Art Gems.” In addition to more celebrated miniaturists, they also prized works by lesser-known painters. Mrs. Starr commented, “A collector comes to love and admire the little pieces. A work of fine craftsmanship, even if it is not pictured in the reference books, has a value all its own.”59“Tiny Art Gems.” They especially cherished their miniatures of children, some of which they held back from their initial gift to the museum, as Mrs. Starr could not bear to part with them; ten of them were featured on the cover of Antiques in 1961 (Fig. 10).60Starr, “Collecting Portrait Miniatures.” Of these, seven remain in the Starr collection. Like many collectors, they were also fascinated with eye miniatures, and they acquired at least forty-one of them “more as curiosities than for their historic worth,” as Mrs. Starr noted.61“Tiny Art Gems.” Their eye miniatures were distributed among several museums, including the Met and the Cleveland Museum of Art, not only as a strategic gesture but also in recognition of the years of support and advice received from curators at those institutions.

In all, the Starrs’ collection of portrait miniatures was dispersed among five different museums across the United States, with each institution carefully selected to reflect its impact on the Starrs as collectors and philanthropists. Beyond the aforementioned gifts of ten eye miniatures to the Met and six to Cleveland, the Starrs gave ten miniatures to the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas, Mr. Starr’s alma mater. Perhaps most significantly, they donated a group of thirty-three miniatures, including three eye miniatures, in 1958—the same year as the Nelson-Atkins gift—to the Philbrook Museum of Art, followed by subsequent gifts in 1961 and 1969. The Philbrook was established by Mrs. Starr’s uncle and aunt, Waite and Genevieve Phillips, who had given the Starrs their first portrait miniature at their wedding in 1929.62As Maggie Keenan details in the Supplement, “Starr Miniatures in Other Collections,” a further thirty-three miniatures were sold at auction at Sotheby’s in two sales in 1982. On March 15, twenty-one portrait miniatures were sold in Silhouettes and Fine Portrait Miniatures (New York: Sotheby Park Bernet and Co., March 15, 1982), and on July 13, twelve eye miniatures were sold in Catalogue of Fine Portrait Miniatures, Russian Works of Art and Objects of Vertu (London: Sotheby’s, July 13, 1982). The Nelson-Atkins received the lion’s share of their miniatures, however: a total of 264 miniatures donated by the family between 1958 and 2018.63Ten portrait miniatures that were purchased independently by the Nelson-Atkins or given by other donors are also featured in the catalogue. Their greatest collecting achievement, above all, remains their carefully and tenaciously assembled collection of Smarts.64The Starrs’ love of John Smart extended to their purchase of a large-scale oil portrait of Smart by Richard Brompton, which hung for many years in their living room. Richard Brompton, John Smart, ca. 1780, oil on canvas, 30 x 25 inches (76.2 x 63.5 cm), Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Starr, 1991.14.1, http://philbrook.emuseum.com/objects/7756/john-smart.

The Starrs were married seventy-two years, until Mr. Starr’s death in 2000.65“Deaths and Funerals,” Kansas City Star, December 20, 2000, B5. Martha Jane Phillips Starr died in 2011, just thirteen days before her 105th birthday. She was eulogized with a formidable list of accomplishments too numerous to enumerate here, not only as a well-known collector of portrait miniatures but as a pillar of the Kansas City community.66Mara Rose Williams, “Shaping the Civic Landscape: Martha Jane Starr, Education, Scouting and the Arts,” Kansas City Star, December 8, 2011, 19. The Starrs’ interests seem widespread but speak to their lifelong determination to, in Mrs. Starr’s words, “make the human family happier.”67“The Martha Jane Phillips Starr Legacy,” Harbor Light, 1. At times their diverse interests were closely linked. In 1965, on the occasion of a dinner held to celebrate the Starrs’ gift of the Smart miniatures, the couple raised $51,000 to establish a Family Studies center at UMKC.68“Family Study Gets Much Needed Push,” Kansas City Star, May 30, 1966, 6.

As their private passion developed into a public cause, the Starrs’ model for philanthropy passed on to the next generation. The Starr Foundation continues to support charitable causes in the Kansas City Area. Indeed, the descendants of John W. and Martha Jane Starr continue to recognize and honor their commitment to portrait miniatures; this essay would not have been possible without the Starr Foundation’s generous support of the collection and catalogue.

Notes

-

An abridged version of this essay appears in Bernd Pappe and Juliane Schmieglitz-Otten, eds., Portrait Miniatures: Artists, Functions, Techniques and Collections (Petersberg: Michael Imhof, 2022), 231–41. I am grateful to Bernd Pappe, Juliane Schmieglitz-Otten, and the Tansey Miniatures Foundation for the opportunity to publish and present my initial findings on the Starrs and their collecting. For the quote from the Starrs, see Martha Jane and John W. Starr, “Collecting Portrait Miniatures,” Antiques (November 1961): 437–41.

-

“The Martha Jane Phillips Starr Legacy,” Harbor Light (November 2017): 1.

-

The development of Woolaroc and the Philbrook Museum is related in Michael Wallis, Oil Man: The Story of Frank Phillips and the Birth of Phillips Petroleum (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2014).

-

Notebook, undated, box 22, folder 10, Martha Jane Starr Collection, LaBudde Special Collections, University of Missouri-Kansas City.

-

Inventory, undated (1930s), box 22, folder 9, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Inventory, undated (1930s).

-

Robert Harshe to Martha Jane Starr, November 1, 1937, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

“Tiny Art Gems to Be Displayed at Nelson Gallery,” Kansas City Star, December 11, 1958, 2.

-

“Tiny Art Gems.”

-

Inventory, undated (1930s).

-

Martha Jane Starr to Maurice Block, January 16, 1940, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Martha Jane Starr to Edward Greene (draft), September 7, 1940, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

For example, in a letter to William G. Constable, curator of painting at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mrs. Starr noted that she was “indebted to Mr. Paul Gardner for his letter to you.” Martha Jane Starr to W. G. Constable, November 6, 1942, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

David J. Trowbridge, Katy Anielak, and Clio Admin, “Starr Women’s Hall of Fame, University of Missouri-Kansas City,” Clio: Your Guide to History, November 16, 2021, https://www.theclio.com/entry/141401.

-

Group of letters, September 12, 1947–February 1948, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Martha Jane Starr to Maurice Block, February 16, 1948, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

As well as being an assiduous correspondent, Mrs. Starr had a unique method for ingratiating herself into the good graces of various curators. There are several notes in the Starr archives thanking Mrs. Starr for sending large boxes of caramels and chocolates that were apparently quite delicious. For example: Catherine Filsinger, assistant curator, City Museum of Saint Louis, to Martha Jane Starr, September 12, 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection; Louise Burchfield, Cleveland Museum of Art, to Martha Jane Starr, perhaps December 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Hans Huth to Martha Jane Starr, March 17, 1948. Mrs. Starr replied on April 3, 1948: “Your letter of March 17, 1984, was received with much interest and I have been having most satisfactory correspondence with Berry-Hill regarding the miniature collection. . . . I am looking forward to seeing them first hand. . . . Mr. Starr and I are anticipating a detailed examination of the pieces. . . . It was most thoughtful of you to refer the name to me and it may result in some additions to our collection.” Mr. Huth later wrote to Mrs. Starr on October 22, 1948: “I am sorry I was not in Chicago when you happened to come in. I am glad you have made some good purchases and I hope to see you next time you are in town.” All three letters, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Duveen Brothers, Miniatures, undated, Special Collections, series I.A., box 15, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, http://hdl.handle.net/10020/2007d1_d0009.

-

To a Mrs. Burrough (presumably Louise Burroughs, with whom Mrs. Starr was a longtime correspondent), October 13, 1947: “Your name was given me by Mr. Paul Gardner, director of the Wm. Rockhill Nelson Art Gallery here in Kansas City, as a person who might be able to assist me in my study and collection hobby of portrait miniatures. I have been collecting for 20 years and after the usual trial and error method now have a small but authentic collection of 17th, 18th, and 19th century miniatures. On several occasions when I have been in New York City, Mr. Wehle has been gracious in seeing my group and advising with me, but now I have come to the stage of needing more counsel and assistance in compiling a catalogue of my collection and further research on this subject”; Martha Jane Starr to Mrs. Burroughs, October 13, 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. To Megrick Rogers, a curator at the Art Institute of Chicago, Mrs. Starr wrote, “Mr. Paul Gardner . . . gave me your name as a person who might help me with my study, research, and collecting of portrait miniatures. This has been my hobby for twenty years, and I am very eager to find an assistant to help compile information I already have and guide me in furthering this work”; Martha Jane Starr to Megrick Rogers, October 13, 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. She wrote to Mr. Greene on the same day, asking about the possibility of viewing his collection in Cleveland; Martha Jane Starr to Edward Greene, October 13, 1947, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971).

-

Wehle wrote to Mrs. Starr with “a review of the principal [collections of miniatures].” Harold Wehle to Martha Jane Starr, March 18, 1948, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

In her reply to Wehle at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Mrs. Starr wrote, “Many thanks for your help and interest. The Starrs like to remember that you were the person directly responsible for our serious interest in collecting and research on historical portrait miniatures.” Martha Jane Starr to Harry Wehle, April 16, 1949, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

“We are most eager to be guided to the proper persons as possible agents [in England], from whom we can develop this program. The sources we know are limited, so we are anxious for your ideas. . . . We hope to visit the famous collections in England before too many years and in the meantime we want to do research on our own. Perhaps you can give us suggestions about the following: How to best authentic[ate] our present group of miniatures; Find reliable sources for further additions of miniatures; Sources for finding new additions for our library; Entrée to the famous collections abroad when we do come over; Names of private collectors and collections in London; Catalogu[e]rs of ‘specific’ collections.” Martha Jane Starr to Graham Reynolds, April 10, 1949, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Group of letters, 1949, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Martha Jane Starr to Harold Wehle, October 7, 1949, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Josephine Allen to Martha Jane Starr, September 8, 1953, curatorial file for “Four Centuries of Miniature Painting–1950,” European Paintings Department, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

These loans are listed in a pamphlet printed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art and digitized by the Met’s Watson Library: Four Centuries of Miniature Painting (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1950), https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll10/id/1175.

-

Catalogue of Fine Portrait Miniatures (London: Sotheby, March 31, 1949), lot 25.

-

Edward Grosvenor Paine to Martha Jane Starr, December 30, 1948, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Catalogue of Fine Portrait Miniatures (London: Sotheby, March 31, 1949), lots 48 and 60; group of letters between Martha Jane Starr and Betty Hogg, n.d., box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Catalogue of Objects of Vertu, Fine Watches and Portrait Miniatures, Including the Property of Mrs. W. D. Dickson; the Property of Mrs. Kehoe (London: Sotheby, June 15, 1950), lots 126, 131, 135–137, 141, 153, 158, 161, 163–64, 168, 172, 174–75. Several of the eighteen miniatures were grouped together in a single lot: 158, 164, and 175 each contained two miniatures.

-

Maggie Keenan took on the tremendous task of scanning these UMKC catalogues and painstakingly documenting the various sale records. UMKC was the selected repository of the Starrs’ archives after the passing of Mrs. Starr, and it logically followed that the Starrs’ sales catalogues, too, were left to the library.

-

See correspondence between Betty Hogg and Martha Jane Starr, May 15 and June 3, 1950, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Betty Hogg wrote to Mrs. Starr on May 15, 1950, regarding her meeting with a “young Mr. Leggatt” and further conversations with a mutual friend, who assured her that the Starrs would be in good hands. In Mrs. Starr’s reply, dated June 3, 1950, she thanked Betty Hogg for connecting them with the Leggatts, writing, “Your Man Mr. L. [Leggatt] has been doing a nice job for us and we have bought at auction several items. Just a week ago we acquired 10 more! So we definitely thank you for your help in getting catalogues . . . and Mr. L. has been great.”

-

Josephine Allen, associate curator, Department of Paintings, Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote to Martha Jane Starr on September 8, 1953, “Don’t I remember that you have some very nice Smart miniatures?” Josephine Allen to Martha Jane Starr, September 8, 1953, curatorial file for John Smart, European Paintings department, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

-

On August 18, 1954, Mrs. Starr wrote to Louise Burchfield: “Not long ago I wrote to Mr. Jaffé regarding help in finding a fine miniature for our October anniversary making Mr. Starr and I twenty-five years together. He had no leads on Hilliards or Olivers but did mention that word had come from you regarding a self portrait of Mr. Smart and that you could probably give us information.” Martha Jane Starr to Louise Burchfield, August 18, 1954, box 18, folder 25, Martha Jane Starr Collection. The spectacular new acquisition, a 1793 self-portrait by Smart, will be published in a catalogue entry in spring 2025, following conservation treatment and new photography.

-

Louise Burchfield to Martha Jane Starr, September 9, 1953, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection. Burchfield wrote, “I had such glowing letters from Mr. Reynolds and Mr. Winter telling how much they enjoyed their visits with you and Mr. Starr. And Mr. Winter spoke especially about the amazingly fine collection you have gathered together.”

-

Carl Winter to Martha Jane Starr, October 11, 1955, box 22, folder 9, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Made under the direction of Jacob Halder, Armor Garniture of George Clifford (1558–1605), Third Earl of Cumberland, 1586, steel, gold, leather, textile, 69 1/2 in. (176.5 cm) high, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Munsey Fund, 1932, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/23939.

-

“Tiny Art Gems.”

-

Martha Jane Starr to Graham Reynolds, April 10, 1949, box 18, folder 27, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Jan Dickerson, “Rare Gifts by Kansas Citians, New Purchases and Loans in Nelson Gallery Exhibit,” Kansas City Star, December 7, 1958, 109.

-

“Tiny Art Gems.”

-

Among many examples are Ross Taggart to Laurence Sickman, October 21, 1971, RG 98-box 08, folder 4, Archives, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art; Ross Taggart to Mr. and Mrs. John W. Starr, November 11, 1971, box 9, folder 3, Martha Jane Starr Collection; John W. Starr to Laurence Sickman, September 14, 1966, box 9, folder 3, Martha Jane Starr Collection.

-

Edward Grosvenor Paine to Daphne Foskett, September 26, 1961, folder 1, Foskett.

-

Mara Rose Williams, “Shaping the Civic Landscape: Martha Jane Starr, Education, Scouting and the Arts,” Kansas City Star, December 8, 2011, 19.

-

I am grateful to Daphne Foskett’s daughter, Helen Godfrey, for her generosity in welcoming me to her home in Edinburgh and sharing recollections about her mother’s writing, collecting, and their friendship with the Starrs.

-

Martha Jane Starr to Mrs. Burton Jones, undated (likely November 1954); Laurence Sickman to Mrs. Burton Jones, November 18, 1964, both letters in the registration files, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. Regarding their inquiry into the whereabouts of Smart miniatures, see also Daphne Foskett to John W. Starr, October 7, 1964, registration files, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

This was in addition to the thirteen miniatures and works on paper by Smart that the Starrs donated with their initial gift in 1958, followed by a further two Smart miniatures in later gifts in 1971 and 1973. In 2018, 2023, and 2024, generous gifts from the Starr family enabled the Nelson-Atkins to acquire three more miniatures by Smart, including a self-portrait.

-

For example, a group of letters from Ross Taggart, August 1965, registration files, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. The seventy Smart miniatures at the Nelson-Atkins include a signed and dated miniature for each year of Smart’s career, from 1760 to 1811.

-

“Painter [sic] of Miniatures to Attend Show Here,” Kansas City Star, November 25, 1965, 10; Donald Hoffman, “400 at Benefit for Gallery—U.M.K.C.—The John W. Starrs Present Their Collection of John Smart Miniatures,” Kansas City Star, December 10, 1965, 3. In 1972, most of the Starrs’ collection was exhibited at the Royal Ontario Museum, which now has several Smarts of its own. “Starr Miniatures,” Toronto Globe and Mail, December 9, 1972.

-

Taggart, Starr Collection of Miniatures, 6–8.

-

Memo from Ross Taggart to Laurence Sickman, June 10, 1974, RG 98-Box 08, Folder 5, Archives, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Merrill C. Rueppel to Laurence Sickman, January 3, 1975; Sickman to Martha Jane Starr, January 8, 1975; Sickman to Rueppel, January 8, 1975. All three letters, RG 98-Box 08, Senior Curator Subject Files, folder 5, Starr Miniature Collection, 1971–1983, Archives, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Ross Taggart to John Walsh, October 8, 1981; Walsh to Taggart, October 15, 1981; Taggart to Martha Jane Starr, October 23, 1981. All three letters, RG 98-Box 08, Senior Curator Subject Files, folder 5, Starr Miniature Collection, 1971–1983, Archives, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Unknown, Portrait of a Man, ca. 1820, 2 5/8 x 2 in. (6.7 x 5.1 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John W. Starr through the Starr Foundation, Inc, F92-27. The Smart grouping includes a sealing-wax impression of John Smart after the medal by Joachim Smith and John Kirk, as well as legal and financial paperwork pertaining to John Smart’s estate; letters written between Smart’s children and the artist Robert Smirke (1752–1845) regarding a gift of a portrait of their father; and a diary kept by Smart’s son John James Smart. These documents are preserved in the Nelson-Atkins archives.

-

According to a pamphlet printed to commemorate the 1992 reinstallation of the Starr miniatures collection, the Starrs’ books on miniatures were placed on deposit at the Nelson-Atkins that year; they are now in the permanent collection of the Spencer Art Reference Library. “The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures,” pamphlet (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1992), registration files, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

“Tiny Art Gems.”

-

“Tiny Art Gems.”

-

Starr, “Collecting Portrait Miniatures.” Of these, seven remain in the Starr collection.

-

“Tiny Art Gems.”

-

As Maggie Keenan details in the Supplement, “Starr Miniatures in Other Collections,” a further thirty-three miniatures were sold at auction at Sotheby’s in two sales in 1982. On March 15, twenty-one portrait miniatures were sold in Silhouettes and Fine Portrait Miniatures (New York: Sotheby Park Bernet and Co., March 15, 1982), and on July 13, twelve eye miniatures were sold in Catalogue of Fine Portrait Miniatures, Russian Works of Art and Objects of Vertu (London: Sotheby’s, July 13, 1982).

-

Ten portrait miniatures that were purchased independently by the Nelson-Atkins or given by other donors are also featured in the catalogue.

-

The Starrs’ love of John Smart extended to their purchase of a large-scale oil portrait of Smart by Richard Brompton, which hung for many years in their living room. Richard Brompton, John Smart, ca. 1780, oil on canvas, 30 x 25 in. (76.2 x 63.5 cm), Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, OK, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Starr, 1991.14.1, http://philbrook.emuseum.com/objects/7756/john-smart.

-

“Deaths and Funerals,” Kansas City Star, December 20, 2000, B5.

-

Mara Rose Williams, “Shaping the Civic Landscape: Martha Jane Starr, Education, Scouting and the Arts,” Kansas City Star, December 8, 2011, 19.

-

“The Martha Jane Phillips Starr Legacy,” Harbor Light, 1.

-

“Family Study Gets Much Needed Push,” Kansas City Star, May 30, 1966, 6.

doi: 10.37764/8322.6.60