Portraits provide visible, tangible reminders of human presence. Portrait miniatures, most less than three inches tall, are even more intimately connected to us. Unlike their larger counterparts in oil, which often hang high up on a wall in homes or at exhibitions, portrait miniatures were designed to be held in one’s hand, extending notions of remembrance between the wearer and the individual represented. Frequently worn on the body as necklaces, rings, or brooches, or hidden for private perusal, they signal love, loss, allegiance, or affection for the subject. Through close study, one can often gain insight into moments that occasioned their production, such as diplomatic gifts, marriage, birth, death, or prolonged periods of absence. No other form of Western portraiture has such deeply personal associations.

Origins of Portrait Miniatures

Scholars believe that there are a number of possible origins for and influences on the development of portrait miniatures. Some point to sonnets by the Italian scholar and poet Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca; 1304–1374), which mention a portable portrait (now lost) of his lover, Laura, by Simone Martini (Italian, about 1284–1344).1See Renzo Baldasso, “Painting Laura: Petrarch’s Renaissance Painting,” Aurora: The Journal of the History of Art 11 (2010), 1–20. Others identify as influential the broader Renaissance interest in classical medals, medallions, coins, and cameos, such as the bronze medals of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, Lord of Rimini (1417–1468) made by modeler, manuscript illuminator, painter, and architect Matteo de Pasti (Italian, 1420–1467), due to their shape and scale (Fig. 1).2See Graham Reynolds, English Portrait Miniatures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 1–4. See also Katherine Coombs, The Portrait Miniature in England (London: V&A Publications, 2005), 16–18. Closest in medium and technique to portrait miniatures, though, is the colorful tradition of illuminated manuscripts, first painted in egg tempera and then later in watercolor on vellum: A fine parchment made of calfskin. A thin sheet of vellum was typically mounted with paste on a playing card or similar card support. See also table-book leaf. between the 1100s and the mid-1500s.3See Renzo Baldasso, “Painting Laura: Petrarch’s Renaissance Painting,” Aurora: The Journal of the History of Art 11 (2010), 1–20. These early illustrated books were made in a variety of sizes and for a variety of purposes, but most were designed to be handheld, with illustrations that roughly matched the scale of miniature portraits.

The small scale of manuscript illuminations and the use of the word “miniatures” to describe them may be where some of the confusion stems over the origin story of portrait miniatures. Contrary to popular belief, the word “miniature” does not, in fact, come from the word “minute” but from the Latin word miniare, which means to color with red lead—a practice employed for the decorative capital letters in early book illustrations (or illuminations, as they were called) from the 1400s. A brilliantly colored example from the Nelson-Atkins collection is the Initial “S” with the Presentation in the Temple (Fig. 2).4Early illuminations appeared in written documents of all types, including devotional, legal, political, and heraldic forms, as noted by Goldring in Nicholas Hilliard, 2. Such illustrations were also called “limning: “Limning” was derived from the Latin word luminare, meaning to illuminate, and the term also became associated with the Latin miniare, referring to the red lead used in illuminated manuscripts, which were also called limnings. Limning developed as an art form separate from manuscript illumination after the inception of the printing press, when books became more utilitarian and less precious. Eventually limning became associated with other diminutive two-dimensional artworks, such as miniatures, leading to the misnomer that “miniature” refers to the size of the object and not its origins in manuscript illumination. Limning is distinct from painting not only by its medium, with the use of watercolor and vellum traditionally used for manuscript illuminations, but also by the typically small size of such works.,” from the Latin word luminare, meaning to give light—a cognate for “illuminations.” In the late 1500s and early 1600s, several miniaturists—including Nicholas Hilliard (English, ca. 1547–1619), who authored a technical treatise on miniature painting called The Art of Limning (ca. 1598), and Edgar Norgate (English, 1581–1650), who authored Miniatura or The Arte of Limning (ca. 1628)—conflated some of manuscript illumination’s terminology with the emerging art of portrait miniatures. Hilliard used the English word “limning” to refer to portrait miniatures, and Norgate used miniature, the Italian word for illuminations, in the same context.5Katherine Coombs unpacks this confusing early history and conflation of terms; Coombs, Portrait Miniature in England, 7. Adding to the confusion, the anglicized version of the word “miniature” gained popularity around the same time, referring to something small in size.6As outlined in Coombs, Portrait Miniature in England, 7. By the 1700s, the term “limning” was interchangeable with “miniature painting.”

While the art of illuminated manuscripts continued into the 1600s, its decline was precipitated by the introduction of the printing press to Europe in the 1450s, which facilitated the reproduction of images and text on a large scale. The proliferation of images led to a greater demand for secular, naturalist works as well as religious texts and, in particular, illustrations, including portraits. Artists began to specialize in portrait work on a small scale, and the demand for miniatures grew. The earliest examples of portrait miniatures independent from the bound vellum manuscript page appeared at the French and English courts in the 1520s.

Materials and Methods

The practice of painting portrait miniatures was not dissimilar to painting illuminated manuscripts. A self-portrait by one of the latter’s greatest practitioners, Simon Benning (or Benninck; Netherlandish, 1483/84–1561), highlights the methods used to paint small-scale pictures (Fig. 3). Both illuminators and portrait miniaturists utilized a slanting easel and relied on natural light. Despite the intimate scale of their work, most artists did not use magnifying tools, although Benning’s glasses suggest the effort required to execute such intricate details. Many artists struggled with their eyesight in their later years, prompting some of them to take up painting in oil due to its larger scale.

Pigments and Brushes

In the 1500s, artists made their own paints from minerals, earth, plants, insects, and gold and silver leaf. These were ground into a fine powder and bound together with gum arabic: Derived from the sap of the African acacia tree, gum arabic was commonly used to bind watercolor pigments with water. In addition to its use as a binder, miniaturists capitalized on its glossy effect to create areas of highlight with larger quantities of gum. As with ivory, its availability benefited from trade routes that were expanding due to colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade. (made from the sap of the acacia tree) and mixed with water or egg yolk (to make tempera). By the 1760s, pigment: A dry coloring substance typically of mineral or organic origins until the nineteenth century, when they began to be artificially manufactured. Pigments were ground into powder form by the artist, their workshop assistants, or by the vendor they acquired the pigment from, before being mixed with a binder and liquid, such as water. Pigments vary in granulation and solubility. were available commercially, and artists no longer needed to make their own. Miniature painters used brushes made out of squirrel hair set in quills and mounted on wooden handles.

Watercolor

Portrait miniature painters used water-based pigments that allowed for more transparency and subtler colors than the egg-based tempera paint used in early book illumination. However, watercolor is extremely sensitive to light and prone to fading. Watercolor is often considered a light and translucent medium, but when ground pigment is blended with a binding agent, typically gum arabic, and mixed with white paint, it can become rich and dense. This medium, called bodycolor, came out of the illuminated manuscript tradition. Bodycolor creates a thick and smooth consistency and was employed to lay in the rich backgrounds and solid dark colors seen, for example, in Benning’s self-portrait. Pure watercolor, without the addition of white, was utilized for finer details such as the features of a sitter’s face.

Vellum

Early miniatures were painted on vellum, generally made of calf, sheep, or goat skin. A naturally hygroscopic material, meaning it easily absorbs moisture from the air, vellum is prone to expand or contract depending on humidity. This shifting can cause destabilization of areas of paint on its surface, resulting in flaking or loss.7For more on the issues with vellum, see Daniel Norman, “The Mounting of Single Leaf Parchment & Vellum Objects for Display and Storage,” Conservation Journal, no. 9 (October 1993), http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/conservation-journal/issue-09/the-mounting-of-single-leaf-parchment-and-vellum-objects-for-display-and-storage. Vellum was more stable when bound into a book, as it would have been when part of a manuscript, which is why when it was used for a single portrait, artists often adhered vellum to a playing card with starch paste to add support. To smooth out any creases in the vellum, artists used a tool—usually an animal’s tooth—to burnish the surface and ensure an even bond between the vellum and the card.

Enamel

Enamel is a type of glass colored by metal oxides and fused to a metal base (usually copper or gold) by firing in a kiln. In the 1630s, the Swiss goldsmith and jeweler Jean Petitot (1607–1691) introduced enamel portraiture to England as a more durable form of miniature than traditional watercolor on vellum. The Swede Charles Boit (1662–1727) continued the practice, and it gained widespread popularity through the works of his student, German artist Christian Friedrich Zincke (ca. 1684–1767). Petitot is known for his rich colors and smooth finish, but many other artists used a stippling: Producing a gradation of light and shade by drawing or painting small points, larger dots, or longer strokes. technique to create the appearance of contour and shadow with tiny dots. Later in his career, Zincke used small red dots, sometimes described as “measles,” which, against the white background, resemble ruddy skin tones (Fig. 4, F58-60/186).

More costly than watercolor miniatures due to their complex and difficult process, enamel paintings were considered a more robust alternative because they did not fade. An artist begins by applying the color that has the highest firing temperature and then applies and fires subsequent layers. The intense firing process in a kiln ensures that the colors do not fade. Risks from firing include cracks and kiln dust, which appears as small black specks.

Plumbago

Toward the end of the 1600s, the plumbago: An archaic term for graphite used by seventeenth-century artists. It originates from the Latin word for lead, plumbum. See also graphite. portrait miniature became popular in England and the Netherlands. Created using graphite: Graphite, or plumbago as it was called in the seventeenth century, is a form of soft carbon, easily sharpened to a point, which deposits a metallic gray color on a surface, ideal for precise writing and drawing. It was first encased in wood in the mid-sixteenth century, a form now referred to as a pencil. See also plumbago. on parchment or vellum, this monochrome portrait medium initially served as the basis for an engraving; however, by the 1700s it became an art form in its own right. While the term “plumbago” generally describes any small, finely worked portrait drawing from the period, it specifically refers to the use of a soft crystalline carbon (graphite or “black lead”). Graphite was initially imported from mines in Bavaria and the Austrian Alps, but by the last quarter of the 1600s rich deposits were being mined in Borrowdale in Cumbria, England, thus making it more accessible—both in terms of price and proximity—to artists working in England.8John Murdoch, Seventeenth-Century English Miniatures in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (London: Stationery Office in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum. 1997), 345, cited in Marjorie Wieseman, “Between Paint and Print: Plumbago Portraits in Britain and the Netherlands,” in Julie Aronson and Marjorie E Wieseman, Perfect Likeness: European and American Portrait Miniatures from the Cincinnati Art Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press: 2006), 33. Borrowdale graphite imparts a lustrous tonal quality to drawings, and its accessibility may have contributed to the dramatic rise in popularity of the art form in England in the 1660s.

Larger than their portrait miniature counterparts, plumbagos are nevertheless typically under six inches in height and were displayed as cabinet miniatures, occasionally framed in small cases for greater portability.9Wieseman, “Between Paint and Print, 33. They were a short-lived phenomenon that fulfilled the desire for detailed portraits at a fraction of the cost of enamels or miniatures painted on vellum, ivory, or other materials. The Nelson-Atkins has a small collection of plumbago portraits done ad vivum by Thomas Forster (English, ca. 1677–after 1712), one of the last and finest practitioners of this medium.

Ivory10The Nelson-Atkins collection of ivory portrait miniatures was acquired prior to the implementation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 and the CITES treaty of 1989, which regulate the trade of ivory—though the miniatures in the collection would have been exempt from the ESA due to their age of more than one hundred years.

The Italian artist Rosalba Carriera (1673–1757) first realized that ivory would be a better support than vellum for the depiction of flesh tones, hair, and textiles because of its inherent luminosity when cut into thin sheets. Portrait miniaturist Bernard Lens III (English, 1682–1740) introduced ivory as a support in Britain around 1707, and it remained the primary support for miniatures until the late 1800s. It was slower to gain currency as a support in France and did not appear until mid-century there, under the skilled guidance of oil painter, miniaturist, and enameller Pierre Adolphe Hall (Swedish, 1739-1793). However, it is not the easiest surface on which to work. Ivory is extremely sensitive and reactive to light, temperature, and humidity changes.11Ivory is sensitive to both sunlight and artificial light, which can damage the surface either through discoloration and/or making it more brittle. Similarly, heat can damage ivory, as can rapid changes in humidity. Ivory wants to return to its original shape as a tooth or a tusk; therefore, museums store ivory miniatures flat in sealed cases to create a stable microclimate. See Meg Craft and Harriet Whelchel, eds., Caring for Your Collections (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 96–107. It absorbs or releases moisture and can shrink, swell, crack, split, and/or warp on exposure to extreme fluctuations in relative humidity and temperature.12Ivory is both hygroscopic and anisotropic, meaning it absorbs and also releases moisture with changing humidity. See Tom Stone, “Care of Ivory, Bone, Horn and Antler,” Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI), Series 6 (Ethnographic Materials), Note 6/1, last modified January 27, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/care-ivory-bone-horn-antler.html.

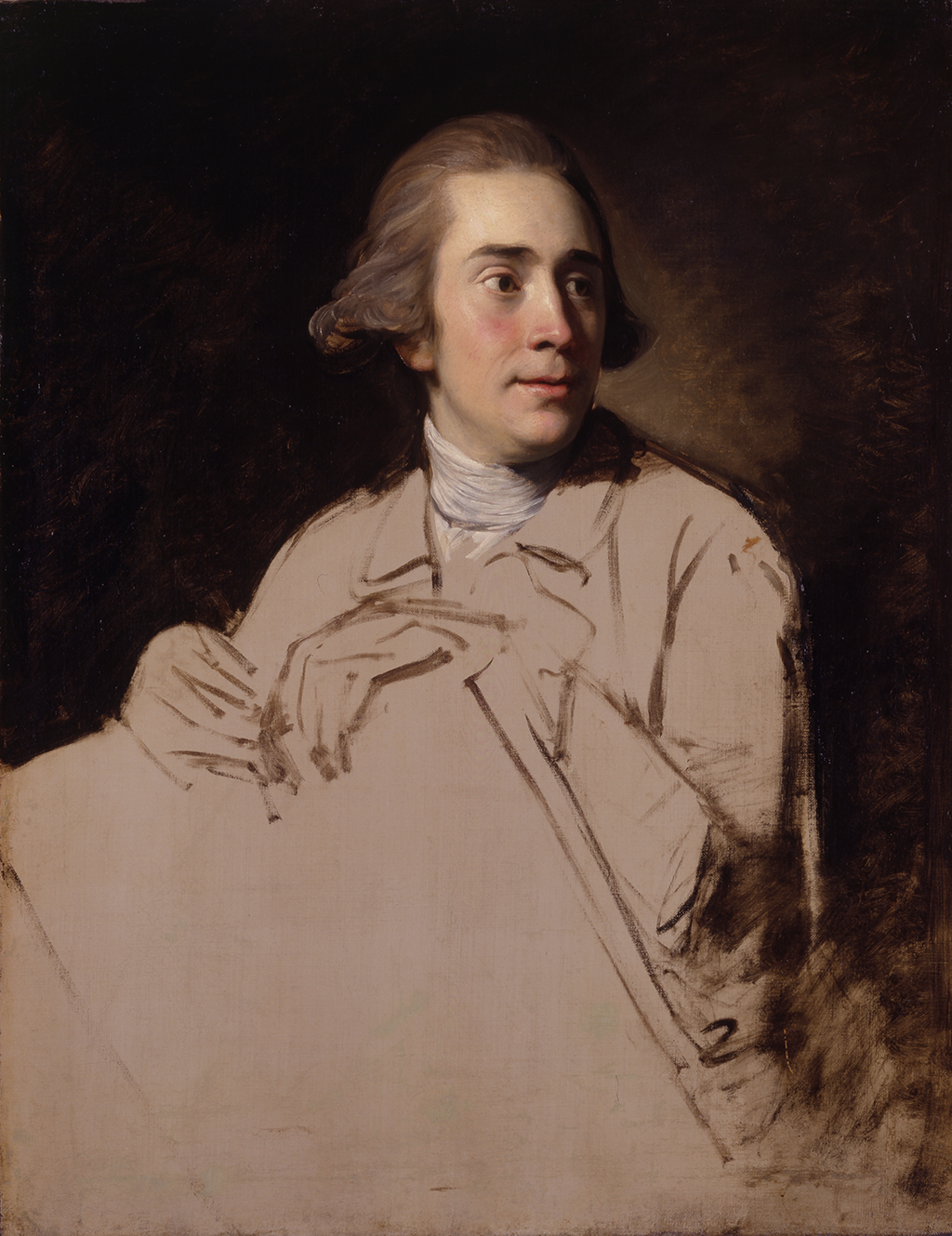

Ivory also has an oily surface that repels water, making it a difficult support on which to paint. Consequently, many early watercolors on ivory reveal mechanical techniques designed to address this challenge, including cross-hatching and stippling. Artists developed methods to facilitate paint adhesion, including roughening the surface of the ivory with powdered pumice stone, degreasing it with vinegar, or, like Jeremiah Meyer (German, 1735–1789; Fig. 5), sanding and polishing the ivory with rushes and cuttlefish bones, applying lemon juice to remove the oils, and adding more binding agents, like gum arabic, to his paint to get it to adhere.13This new research on Meyer’s materials and techniques is published in Peter Knaus and Luise Schreiber-Knaus, “The Life and Career of Jeremiah Meyer RA (1735–1789) During the Reign of King George III,” Portrait Miniatures: Artists, Functions, Techniques, and Collections, eds. Bernd Pappe and Juliane Schmieglitz-Otten (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2023), 113. Hall introduced an innovative painting technique on ivory known as stippling, or pointillé, which had been in use on the Continent since the 1600s. This technique ushered in a completely new approach to painting, applicable to both enamel portraits and watercolor miniatures. It facilitated the portrayal of shadow by using small dots or hatches shaped like short commas, strategically spaced to indicate darker and lighter areas of the composition, such as the sitter’s face and clothing. The concentration of dots in darker areas and their spacing in lighter areas allowed for a nuanced depiction. The smoother the appearance of the miniature, the finer and less visible these dots became.

When ivory replaced vellum as the primary support for portrait miniatures, the size of miniatures decreased, due in part to the difficulty of painting in watercolor on a slippery ivory surface. Enamels were also popular at this time, and their diminutive scale may also have informed the smaller size of miniatures on ivory.

Viewing and Consuming Portrait Miniatures

Portrait miniatures evolved from a private possession in the 1500s and 1600s to a variety of semipublic and public forms of display in the mid- to late 1700s.14For more on the private nature of miniatures at the court of Elizabeth I, see Patricia Fumerton, Cultural Aesthetics: Renaissance Literature and the Practice of Social Ornament (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), cited in Marcia Pointon, “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England,” Art Bulletin 83, no. 1 (March 2001): 58n49. For an example of a semiprivate collector’s cabinet from the 1700s, see Horace Walpole’s miniature cabinet at Strawberry Hill: “The Walpole Cabinet,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed March 1, 2023, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/w/walpole-cabinet. In 1768, following the opening of the Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. in London, miniatures began to occupy space on the exhibition walls every spring and summer, allowing patrons the opportunity to view these intimate keepsakes publicly. You can see some on display in the lower register of the middle of the right wall in the etching of the Royal Academy exhibition in 1787 (Fig. 6). It is no coincidence that the first account of an individual wearing a miniature pendant at court occurred within a year of the academy’s opening.15Elizabeth Pierrepont (née Chudleigh), the Duchess of Kingston, wore a miniature portrait of Frederick Augustus I (1750–1827), who reigned as the last Elector of Saxony from 1763 to 1806, when she was presented at court in 1769. See Pointon, “Surrounded with Brilliants,” 53n19. These very visible venues—exhibitions and the Georgian court—encouraged the wearing of miniatures to signal one’s allegiance to a person or to the state. In fact, Queen Charlotte (1744–1818) picked up on the trend and appears in numerous portraits wearing miniatures of her husband, George III (1738–1820), set as a bracelet, as seen in an example by the German painter Johan Zoffany (1733–1810; Fig. 7).

As sentimental objects, miniatures were often worn on one’s body and set into jewelry, including rings, pendants, and bracelets. However, in the Georgian era, social decorum allowed women to wear images only of their children, deceased loved ones, or their husbands, whereas men, who certainly owned and valued miniatures, risked detriment to their masculinity if they wore them publicly at all.16As discussed in Pointon, “Surrounded with Brilliants,” 59. (This did not apply to the unique art form of eye miniatures, discussed below.) Over time, bracelet straps—often made of ribbon or cord—disintegrated or became separated from the miniatures and were sometimes replaced in later eras with updated straps, to make them fashionable and functional again. Such is the case with the braided hair bracelet that was probably added in the 1840s to a miniature by Gervase Spencer (1715–1763; Fig. 8, F58-60/147). Even in the absence of a bracelet band, it is still possible to determine from its case if a portrait is in a bracelet miniature setting. Bracelet cases bear an extended bracket with pierced holes for the bracelet cords: Twisted or braided three-dimensional rope, often seen on or hanging from the shoulder., as seen on the back of another miniature by Spencer (Fig. 9, F58-60/149). Bracelet miniatures also have a slightly concave back to conform to the shape of one’s wrist, thus maintaining contact with the wearer’s body and extending the connection beyond the emotional to the physical.17For a discussion of the social context and patterns of commodity and exchange for portrait miniatures, see Pointon, “Surrounded with Brilliants.”

Although portraits were initially associated primarily with royalty and heads of state, the expanding market economy and the growth in romantic sensibility by the mid-1700s increased the demand for miniatures (and portraits in general), and they became more widely available to merchants and members of the military. By the 1770s, portraiture reached newfound levels of popularity; an anonymous author writing in 1777 declared that “in former times, Families of Distinction and Fortune alone employed the Painter in this line of the Profession. But in these days, the Parlour of the Tradesman is not considered as a furnished room, if the Family-Pictures do not adorn the wainscot.”18Anonymous [William Combe], A Poetical Epistle to Sir Joshua Reynolds, Knt. and President of the Royal Academy (London: Fielding and Walker, 1777), unpaginated. For these upwardly mobile individuals, portraits and portrait miniatures registered status and acted as a surrogate for the individual in life or in death.

Mourning miniatures filled a special need “to keep the dead within the circle of the living.”19Robin Jaffee Frank, Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 139. Miniatures commissioned to commemorate the dearly departed often contained complex iconography on their cases. During the early 1700s, skulls or skeletons often appeared entombed inside coffin-like crystals, as seen in an example from a private collection (Fig. 10). The neoclassical trend of the 1770s and beyond was reflected in allegorical figures dressed in classical attire and standing over Grecian urns or Egyptian obelisks—or, as on the reverse of Portrait of a Woman by John Smart (English, 1741–1811), sitting at a headstone bearing the name of the deceased (Fig. 11, F65-41/26). Painted likenesses of lost loved ones were often combined with their hair and seed pearls, symbolizing tears; both elements are present in the Smart miniature. Hair became a mainstay of mourning miniatures and is also frequently featured on the backs of miniatures given as tokens of love. Because hair does not decay, it connected those lost to the living on a physical level.

A more enigmatic form of connection between giver and recipient informed the production of eye miniatures, a peculiar and ephemeral trend in miniature painting that emerged in the late eighteenth century (Fig. 12, F58-60/194). These miniatures represent an intensified expression of an already emotionally charged art, made with the intention of revealing an individual’s innermost thoughts and feelings by depicting the so-called window of the soul. While some eye miniatures were turned into captivating jewelry pieces, others have a disconcerting quality to them, as disembodied eyes float eerily against a backdrop of clouds.

The symbolism of the eye in art is complex and multivalent; however, in Britain, eye miniatures served primarily as tokens of love. The idea was that it represented the giver’s eye and was presented to a loved one. The recipient could then wear it publicly, as it would be recognizable only to them, thus keeping their lover’s identity a secret.20For more on eye miniatures, see the essay by Maggie Keenan included in the third launch of this publication, slated for the fall of 2024.

Notable Artists and Works

Although miniatures first appeared at the French and English courts in the 1520s, examples from this period are rare. One of the museum’s earliest and most exceptional examples was realized around 1587 by English artist, Nicholas Hilliard, one of the most famous practitioners of the Elizabethan era (1558–1603). Following Queen Elizabeth I’s order that no hint of shadow should cloud the royal face, many artists depicted her and other patrons in a two-dimensional style. Hilliard was originally trained as a goldsmith, and some of his technical practices in miniatures reflect this training. Instead of using gold or silver pigment, Hilliard used real gold and silver leaf to depict his sitter’s dress, as in the details of George Cumberland’s etched and gilded Greenwich armor (Fig. 13, F58-60/188).21For more on Hilliard’s technique and practice, see Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard, especially 9–14.

The 1600s saw the rise of Samuel Cooper (English, ca. 1608–1672), an internationally renowned miniaturist and painter to both Parliamentary: During the English Civil War (1642–1651), the Parliamentary cause was embraced by opponents of absolute monarchy who sought to depose King Charles I and later executed him. and Royalist: A supporter of monarchy or specific monarchs. In the context of the English Civil War (1642–1651), Royalists supported the absolute monarchy of King Charles I, who fought against the Parliamentary armies of Oliver Cromwell to protect the king and his divine right to rule. See also Parliamentary, Roundheads. during the English Civil War (1642–1651). Following the Restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, he counted King Charles II (1630–1685) among his most important patrons. Cooper’s skill lay in his ability to communicate character through the subtlety of his coloring and mastery of the watercolor medium. Once he established his own studio around 1641, he quickly became the most sought-after miniature painter of his generation, charging twenty pounds for a head and thirty pounds for a half-length portrait by the end of his long career; these prices are comparable to what his colleagues charged one hundred years later.

Like Hilliard, miniature painters during the 1500s and 1600s often came from other professions, such as goldsmithing or watchmaking, and were trained in miniature painting through an apprenticeship system. However, this began to change in the late 1760s with the emergence of professional art schools, including William Shipley’s Drawing School and the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Immediately preceding the professionalization of the genre at this time, artists like Samuel Collins (English, ca. 1735–1775) and Luke Sullivan (Irish, 1705–1771) created works that were small (one to two inches high) and painted with an unpretentious naturalism. This earned them the posthumous nickname “The Modest School.” Despite the challenges of painting in watercolor on ivory, these miniaturists succeeded in creating a new and distinct national style by the mid-eighteenth century, paving the way for the more daring works of future generations.

The reigns of George III (r. 1760–1820) and George IV (r. 1820–1830) marked the zenith of portrait miniature painting in Britain and represent the greatest area of strength in the Starr Collection. In the 1760s, a new wave of artists emerged who took miniature painting to new heights. These academically trained artists—including Jeremiah Meyer, Richard Cosway (English, 1742–1821), John Smart, and later George Engleheart (English, 1750–1829)—painted on a larger scale (often exceeding three inches), and developed styles and techniques that better highlighted the luminous qualities of ivory.

These miniaturists not only stood out in their field but also ranked among the greatest portraitists of the age, alongside oil painters such as Thomas Gainsborough (English, 1727–1788), Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–1792), and George Romney (English, 1734–1802). Additionally, numerous other skilled miniature painters developed their own unique styles. The number of artists proliferated in tandem with the interest in having one’s portrait painted, and by the end of the 1700s, there were more than sixty practicing miniature painters in central London.

In the United States, the tradition of miniature paintings was carried on by some of the country’s most skilled oil painters. The Peale brothers, Charles Willson Peale (1741–1827) and James Peale (1749–1831), produced delicate and nuanced miniature (as well as full-scale) portraits for their clients in Philadelphia, while James’s daughter, Anna Claypoole Peale (1791–1878) was highly sought after by the elite of Boston and Philadelphia. Meanwhile, in New York, the Irishman John Ramage (ca. 1748–1802) painted the country’s first president, as well as other individuals who likely ran in important social and political circles (Fig. 14, F58-60/114).

During the late eighteenth century, numerous miniaturists from Great Britain, France, and Italy traveled to the United States to paint portraits of the citizens of the new republic. British artists introduced a larger and more radiant type of miniature, while those from the Continent brought their precise and ornamental style. These artists had a long-lasting impact on the American market for miniatures, which experienced a significant surge in popularity in the following century.22This brief overview of American artists is drawn from Carrie Rebora Barratt, “American Portrait Miniatures of the Eighteenth Century,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, October 2003, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mini/hd_mini.htm. See also Dale T. Johnson, American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990).

Women Artists

Portrait miniatures’ anatomical focus on the head, rather than the body, opened up the genre to women practitioners, most of whom would not have had access to traditional life-drawing classes. Two women represented in the Nelson-Atkins collection were members of artistic families with whom they were able to study and learn their trade. These include Susannah-Penelope Rosse (née Gibson; English, ca. 1655–1700) and Anna Claypoole Peale. Whereas Rosse probably worked largely for herself or her family’s collection, rather than for paying clients, a little over a century later, Peale actively sought and secured many commissions.23John Murdoch suggests this possible reading of Susannah-Penelope Rosse’s output. See John Murdoch, “Rosse, Susannah-Penelope (c. 1655–1700),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10633. The genre of portrait miniature painting was socially acceptable as a practice for women, but the ways in which both artists engaged with it, either through marketing themselves and selling their work or competing with male painters at public exhibitions, was unconventional.24In 1822, William Dunlap edited the memoirs of Charles Brockden Brown (1771–1810), which included Brown’s essay on the social attitudes and options open to women in the United States, titled Two Dialogues: The First on Music, the Second on Painting, as a Female Accomplishment, or Mode of Gaining Subsistence and Fortune. Brown compares the two artistic pursuits of music and art and then offers writing as a third discipline he felt offered an easier path for women to retain their dignity through anonymity. “The implements and materials [of a writer] were cheap & to be wrought . . . with less exposure to the world, less personal exertion, less infringement of liberty.” To gain a living in music, meanwhile, women had to “shew [themselves] at concerts,” and by doing so, Brown argued, they “forfeit all esteem and trample upon delicacy.” See Charles Brockden Brown, Memoirs of Charles Brockden Brown, the American Novelist, ed. William Dunlap (London: H. Colburn & Company, 1822), 330–31. There were countless additional women miniature painters, many of whose names are not yet known, who require further research and time to be discovered.

The Decline in Miniature Painting and Its Legacy

In the mid- to late 1800s, portrait miniatures began to decline in popularity as artists created larger works in order to compete with oil paintings. William Charles Ross’s (English, 1794–1860) beautiful 1832 watercolor-on-ivory portrait of Miss Mary Pack (Fig. 15, F71-29/4), when measured in its ornate ormolu: A gold-colored alloy consisting of copper, zinc, and tin. frame, is nearly five inches tall—compared to miniatures produced earlier in the century, which averaged around two inches tall. The advent of photography in the mid-nineteenth century further impacted the popularity of portrait miniatures, as people sought to capture more detailed and accurate representations of themselves and their loved ones. Despite this decline, portrait miniatures continued to hold significance for those who appreciated the intimacy and personal nature of these works.

In many ways, portrait miniatures of the past offer a fascinating connection to the present, particularly in this era of social media and smartphones. While the means of production have changed, the underlying human desire to capture and preserve likenesses persists. Selfies, much like portrait miniatures, serve as tokens of love, loss, and affection exchanged among friends and intimates. They provide tangible reminders of human presence, preserving fleeting moments for posterity. Both miniatures and selfies illustrate the human impulse to connect and be remembered, a desire that has remained unchanged throughout time. As we continue to document our lives and capture memories through new technologies, at the core is a universal yearning for connection and immortality, like the individuals who commissioned and painted portrait miniatures in previous centuries.

Notes

-

See Renzo Baldasso, “Painting Laura: Petrarch’s Renaissance Painting,” Aurora: The Journal of the History of Art 11 (2010), 1–20.

-

See Graham Reynolds, English Portrait Miniatures (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 1–4. See also Katherine Coombs, The Portrait Miniature in England (London: V&A Publications, 2005), 16–18.

-

Illuminated manuscripts were produced initially by monasteries, but wealthy patrons also wanted illustrated works for their personal libraries and encouraged the formation of private workshops that flourished in French and Italian cities in the 1200s through the 1400s. For a larger discussion of the roots of limning, or miniature painting, see Elizabeth Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard: Life of an Artist (New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2019), 4–7.

-

Early illuminations appeared in written documents of all types, including devotional, legal, political, and heraldic forms, as noted by Goldring in Nicholas Hilliard, 2.

-

Katherine Coombs unpacks this confusing early history and conflation of terms; Coombs, Portrait Miniature in England, 7.

-

As outlined in Coombs, Portrait Miniature in England, 7.

-

For more on the issues with vellum, see Daniel Norman, “The Mounting of Single Leaf Parchment & Vellum Objects for Display and Storage,” Conservation Journal, no. 9 (October 1993), http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/journals/conservation-journal/issue-09/the-mounting-of-single-leaf-parchment-and-vellum-objects-for-display-and-storage/.

-

John Murdoch, Seventeenth-Century English Miniatures in the Collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (London: Stationery Office in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum. 1997), 345, cited in Marjorie E. Wieseman, “Between Paint and Print: Plumbago Portraits in Britain and the Netherlands,” in Julie Aronson and Marjorie E. Wieseman, Perfect Likeness: European and American Portrait Miniatures from the Cincinnati Art Museum (New Haven: Yale University Press: 2006), 33.

-

Wieseman, “Between Paint and Print,” 33.

-

The Nelson-Atkins collection of ivory portrait miniatures was acquired prior to the implementation of the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of 1973 and the CITES treaty of 1989, which regulate the trade of ivory—though the miniatures in the collection would have been exempt from the ESA due to their age of more than one hundred years.

-

Ivory is sensitive to both sunlight and artificial light, which can damage the surface either through discoloration and/or making it more brittle. Similarly, heat can damage ivory, as can rapid changes in humidity. Ivory wants to return to its original shape as a tooth or a tusk; therefore, museums store ivory miniatures flat in sealed cases to create a stable microclimate. See Meg Craft and Harriet Whelchel, eds., Caring for Your Collections (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 96–107.

-

Ivory is both hygroscopic and anisotropic, meaning it absorbs and also releases moisture with changing humidity. See Tom Stone, “Care of Ivory, Bone, Horn and Antler,” Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI), Series 6 (Ethnographic Materials), Note 6/1, last modified January 27, 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/conservation-institute/services/conservation-preservation-publications/canadian-conservation-institute-notes/care-ivory-bone-horn-antler.html.

-

This new research on Meyer’s materials and techniques is published in Peter Knaus and Luise Schreiber-Knaus, “The Life and Career of Jeremiah Meyer RA (1735–1789) During the Reign of King George III,” Portrait Miniatures: Artists, Functions, Techniques, and Collections, eds. Bernd Pappe and Juliane Schmieglitz-Otten (Petersberg: Michael Imhof Verlag, 2023), 113.

-

For more on the private nature of miniatures at the court of Elizabeth I, see Patricia Fumerton, Cultural Aesthetics: Renaissance Literature and the Practice of Social Ornament (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991), cited in Marcia Pointon, “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England,” Art Bulletin 83, no. 1 (March 2001): 58n49. For an example of a semiprivate collector’s cabinet from the 1700s, see Horace Walpole’s miniature cabinet at Strawberry Hill: “The Walpole Cabinet,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed March 1, 2023, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/w/walpole-cabinet/.

-

Elizabeth Pierrepont (née Chudleigh), the Duchess of Kingston, wore a miniature portrait of Frederick Augustus I (1750–1827), who reigned as the last Elector of Saxony from 1763 to 1806, when she was presented at court in 1769. See Pointon, “Surrounded with Brilliants,” 53n19.

-

As discussed in Pointon, “Surrounded with Brilliants,” 59.

-

For a discussion of the social context and patterns of commodity and exchange for portrait miniatures, see Pointon, “Surrounded with Brilliants.”

-

Anonymous [William Combe], A Poetical Epistle to Sir Joshua Reynolds, Knt. and President of the Royal Academy (London: Fielding and Walker, 1777), n.p.

-

Robin Jaffee Frank, Love and Loss: American Portrait and Mourning Miniatures, exh. cat. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 139.

-

For more on eye miniatures, see the essay by Maggie Keenan included in the third launch of this publication, slated for the fall of 2024.

-

For more on Hilliard’s technique and practice, see Goldring, Nicholas Hilliard, especially 9–14.

-

This brief overview of American artists is drawn from Carrie Rebora Barratt, “American Portrait Miniatures of the Eighteenth Century,” in Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, October 2003, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/mini/hd_mini.htm. See also Dale T. Johnson, American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990).

-

John Murdoch suggests this possible reading of Susannah-Penelope Rosse’s output. See John Murdoch, “Rosse, Susannah-Penelope (c. 1655–1700),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10633.

-

In 1822, William Dunlap edited the memoirs of Charles Brockden Brown (1771–1810), which included Brown’s essay on the social attitudes and options open to women in the United States, titled Two Dialogues: The First on Music, the Second on Painting, as a Female Accomplishment, or Mode of Gaining Subsistence and Fortune. Brown compares the two artistic pursuits of music and art and then offers writing as a third discipline he felt offered an easier path for women to retain their dignity through anonymity. “The implements and materials [of a writer] were cheap & to be wrought . . . with less exposure to the world, less personal exertion, less infringement of liberty.” To gain a living in music, meanwhile, women had to “shew [themselves] at concerts,” and by doing so, Brown argued, they “forfeit all esteem and trample upon delicacy.” See Charles Brockden Brown, Memoirs of Charles Brockden Brown, the American Novelist, ed. William Dunlap (London: H. Colburn & Company, 1822), 330–31.

doi: 10.37764/8322.6.50