Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or not) for Pink Hair,” essay in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.6.94.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or not) for Pink Hair,” essay. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.6.94.

The Starr Collection of portrait miniatures at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art features seventy-one works by John Smart (1741–1811), spanning nearly every year of his prolific career. Amid this extensive collection—and indeed throughout Smart’s body of work—a striking phenomenon surfaces: the portrayal of sitters with pink or lilac-tinged hair, appearing consistently from his initial period in London (1760–1785) through his years in India (1785–1795) and his return to London (1795–1811).

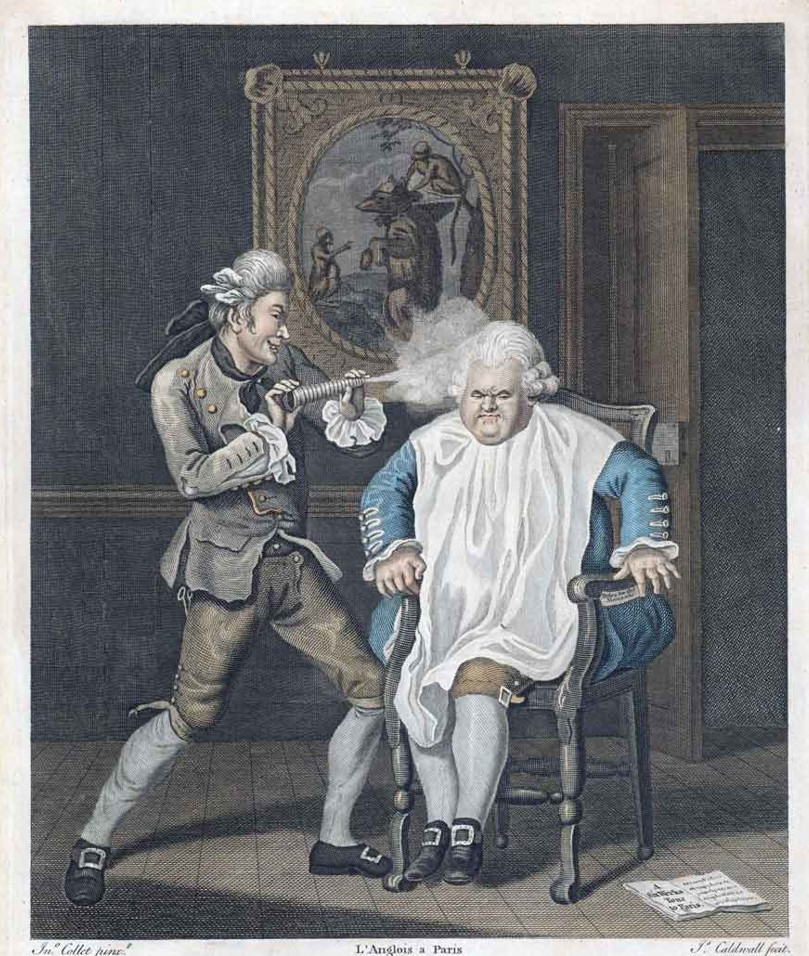

Pink hair powder, though rare, did appear occasionally in period advertisements, literature, and caricatures, but its actual prevalence in eighteenth-century English portraiture remains largely speculative. Most individuals wore their hair in natural hues such as brown, blond, red, or black, while the ultra-fashionable set, including the landed aristocracy, crown, and court, generally opted for powdered white or grayish-white hair. This trend is frequently mocked in caricatures of the period that show sitters enveloped in white powder clouds, particularly when seated before foreign, mostly French, hairdressers (Fig. 1). Evidence of this convention is visible in the dusted collars and shoulders of sitters’ coats seen in many of Smart’s own portrait miniatures, including that of the infamously corrupt John Holland.

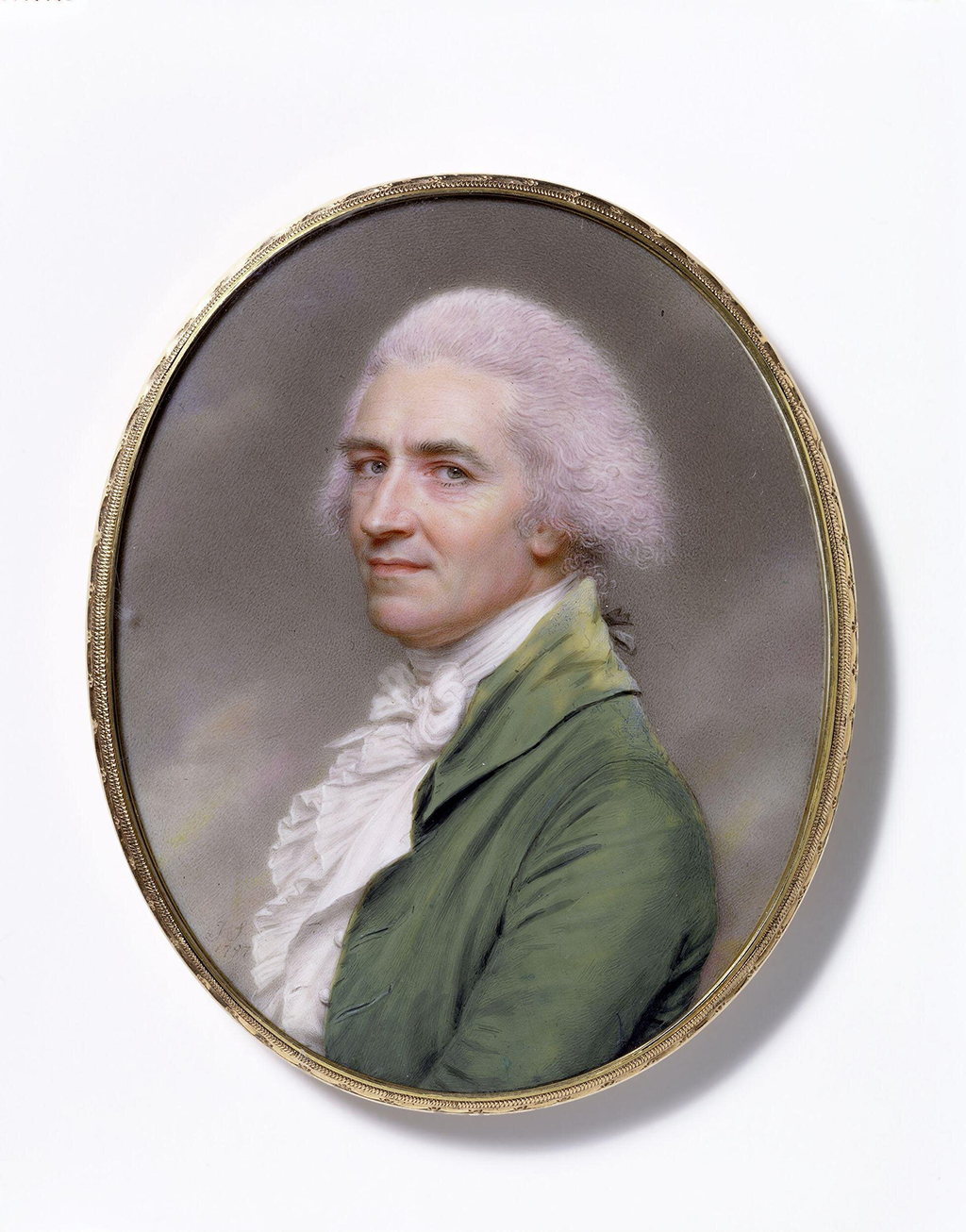

Smart’s primary rival in miniature, Richard Cosway (1742–1821; see Portrait of Lady Charlotte FitzGerald, later 21st Baroness de Ros, 1791), and contemporaries in oil painting, such as Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788; Fig. 2) and Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792; Fig. 3), frequently depicted fashionable elites with powdered white or grayish-white hair, a visual marker of their high social status. By contrast, Smart’s clientele primarily consisted of the merchant and military classes, who valued portraiture as a means of documenting their newfound status and wealth. While many of these sitters may have preferred realistic and timeless depictions, others might have embraced more expressive or experimental trends, including the use of pink hair powder.

Smart’s background as the son of a wigmaker may have heightened his attention to coiffures and helped him connect with a diverse clientele.1For more on Smart’s father and his profession, see Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Painter of the People: John Smart in London, 1741–1785.” Notably, Smart portrayed his own hair in a lilac hue in his 1797 self-portrait—a bold nod to the powdered hairstyles he so often depicted (Fig. 4). Yet the question remains: Would his patrons have chosen to be represented with pink hair—a fleeting fashion that risked appearing quickly outdated? Alternatively, could certain miniatures’ pink hue result from fugitive pigments: Fugitive pigments are not lightfast, which means they are not permanent. They can lighten, darken, or nearly disappear over time through exposure to environmental conditions such as sunlight, humidity, temperature, or even pollution. and age-induced color alterations, since pigment: A dry coloring substance typically of mineral or organic origins until the nineteenth century, when they began to be artificially manufactured. Pigments were ground into powder form by the artist, their workshop assistants, or by the vendor they acquired the pigment from, before being mixed with a binder and liquid, such as water. Pigments vary in granulation and solubility. are known to degrade, sometimes leaving unexpected tones?

Whether the pink hair observed in Smart’s work is a fashionable affectation, a technical artifact, or some combination of the two, it is a striking and distinctive feature of his work that merits further consideration.

Period Trends: Hair Powder

Although eighteenth-century hairstyles often involved white powder, colored powders were also available.2Curiously, some have questioned whether “pink powder” might refer to pigments like Dutch pink, a yellowish hue derived from ripened buckthorn berries. While Dutch pink was commonly used in artistic contexts, particularly for its soft, muted tones, period references to “pink powder” seem to align more consistently with the modern understanding of pink—brighter, more vivacious, and often associated with the fashion-forward circles of the time. This contrast suggests that Dutch pink was probably not the source for the hair powder referred to in fashion and literary references, a conclusion supported by its lack of appearance in recipe books for hair powder or blush during the period. It does not appear, for example, in the recipes for any type of face paint in Pierre-Joseph Buc’hoz, The Toilet of Flora: Or, a Collection of the Most Simple and Approved Methods of Preparing Baths, Essences, Pomatums, Powders, Perfumes, and Sweet-Scented Waters, With Receipts for Cosmetics of Every Kind. . . . rev. ed. (London: J. Murray and W. Nicoll, 1784). For Dutch pink’s applications in painting, see n. 25. For example, a 1778 advertisement by the Bath perfumer Berwick lists shades such as poudre-maréchale (a reddish-brown powder also called French Rose Maréchale), violet, brown, pink, gray, and white.3“Berwick of London,” Bath Chronicle, January 1, 1778. As a selling point, the advertisement signals that many of the items for sale have “just arrived from abroad.” While colored powder was strongly associated with French tastes—particularly the fashion influence of Madame de Pompadour, mistress to King Louis XV;4See, for example, François Boucher, Pompadour at Her Toilette, 1750, with later additions, oil on canvas, 31 15/16 x 25 9/16 in. (81.2 x 64.9 cm), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA, 1966.47, https://hvrd.art/o/303561. The painting is a vivid celebration of pink, reflecting its connection to both cosmetics and high fashion. Marie Antoinette, queen to Louis XVI;5Marie Antoinette was also strongly associated with colored hair powder. Period accounts note that she wore Rose Maréchale powder, which perfumers touted as heightening the complexion. See [George Smith and William Makepeace Thackeray, eds.], “Paint, Powder, and Patches,” Cornhill Magazine 7 (June 1863): 739. and the aristocratic subculture of post-Revolutionary France (Fig. 5)—its appeal extended to English elites. The Whig: Initially forming in England as a political faction and then as a party, Whigs supported a parliamentary system and espoused ideals of liberalism and economic protectionism. Their opposing party were the Tories. politician Charles James Fox, who sported blue hair powder, red heels, and a French accent after returning from abroad, drew both admiration and criticism for his embrace of French fashion, underscoring the period’s complex relationship with imported styles.6While Fox eventually stopped wearing blue hair powder, the color became associated with his Whig party politics; see Philopatris Varvicensis [Samuel Parr], Characters of the Late Charles James Fox (London: J. Mawman and Poultry, 1809), 1:111. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, criticized his display and affectation of French fashions as unpatriotic; see Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, The Sylph: A Novel, ed. Jonathan Gross (1779; repr. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2007), xix.

Pink powder was rarer in English society, but it is mentioned in works of popular culture. In a passage in Anna Maria Bennett’s 1785 novel, Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress, the heroine, Anna, describes her friend Cecilia Edwin, with her pink-powdered hair, as:

a kind of middle character, between a sentimental novelist, and a town coquette. Her dress was so much to the very extreme of the fashion, that . . . she was an object of wonder and curiosity, for she had the satisfaction of being generally stared at in the metropolis. Her clear brown complexion, where the blood had formerly been seen to mount on every occasion, was now hid by the politer daubings of rouge; and her fine glossy black hair, lost in a paste of pink-powder and pomatum.7Agnes Maria Bennett, Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress, Interspersed with Anecdotes of a Nabob (London: William Lane, 1785), 2:54–55.

This description of pink-powdered hair as daring and provocative contrasts sharply with the understated elegance of Smart’s pink-haired sitters in the Nelson-Atkins collection. For instance, the woman featured in a 1772 portrait exudes an elegance and refinement that defies the association of pink hair with extreme or sensational fashion. This sitter, with her poised demeanor, represents a more reserved use of pink powder—an attempt to align with contemporary trends while maintaining a composed and dignified appearance.

However, the pink-haired sixteen-year-old Mary Lewin, née Hale (Fig. 6) appears in Smart’s portrait with a bright smirk and hat perched sideways in a playful and assertive pose, embracing a more flirtatious and coquette-like attitude. Hale’s portrait suggests that for some sitters, pink powder was used to signal not only fashionable awareness but also social aspirations. Her new husband, Thomas Lewin, served as the official correspondent for the British-ruled province of Madras when he was in India and was part of Marie Antoinette’s retinue while he was in Paris,8See the essay for lot 22, A Life’s Devotion: The Collection of the Late Mrs T.S. Eliot (London: Christie’s, November 20, 2013), https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5733065. further positioning Hale within a network of emerging elites who were defining their identity through the adoption of fashionable trends like pink powder. Smart’s portraits of these sitters show how pink hair was a flexible signifier, simultaneously capturing the exuberance of new wealth and the desire to blend into elite circles.

Pink hair powder was not the exclusive domain of women. A satirical verse from 1780 describes a clergyman who, mid-service, “turn’d round, why? To see his pink powder,” suggesting his eagerness to display his fashionable affectations9“Another, who here on a Sunday does duty/ Sometimes, and is thought by himself a great beauty;/ In the service each word rises louder and louder, / ‘Till he’ave turn’d round, why? to see his pink powder, / With his little starch’d band, and an u-ly p-g face, / He thinks himself doubtless, the king of the place.” “Mrs. P—g, to Miss Nancy S—ds,” in X. Y., Cheltenham: A Fragment, with Explanatory Notes (London: G. Robinson and S. Harward, 1780), 12.—a sharp contrast to Smart’s restrained depiction of the gray-haired Reverend Richard Sutton Yates. While the clergyman’s turning around could imply an attempt to show off his artificially enhanced cheeks, the term “pink powder” more commonly refers to hair powder in eighteenth-century fashion, as blush would have been called rouge or face paint. Pink hair powder was often applied selectively to the top or sides of the hair, as seen in Smart’s portrait of Mrs. John Chamier (Fig. 7), and it is possible the clergyman’s display followed a similar practice. In a fashionable spa town like Bath, where social judgment hinged on personal style and the seasonal elite gathered to see and be seen, it is especially striking that a clergyman succumbed to such a folly of fashion.

This context parallels Matthew (or Matthias, ca. 1721–1780) and Mary Darly’s (1760–1781) satirical “macaroni: A fashionably dressed man who wore a tight suit with rich and colorful textiles.” prints, which documented more than 150 individuals from various walks of life whose fashion “exceeded the ordinary bounds.”10Amelia F. Rauser, “Hair, Authenticity, and the Self-Made Macaroni,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 1 (October 2004): 101. See, for example, Matthew Darly and Mary Darly, The Original Macaroni, 1772, hand-colored etching on laid paper, sheet: 8 5/8 x 5 9/16 in. (21.9 x 14.1 cm), plate: 7 x 5 in. (17.8 x 12.7 cm), Colonial Williamsburg, https://emuseum.history.org/objects/12336/the-original-macaroni. Despite the prevalence of these prints, however, pink hair and such flamboyant forms of dress and affectation are mostly absent in larger-scale oil portraits, suggesting that pink powder might have occupied a liminal space—one that existed between the realms of high fashion and satire. This theory is complicated by the fact that by 1798, Smart’s miniatures commanded prices on par with oil portraits by leading artists like Gainsborough and Reynolds.11By 1798, Smart charged twenty-five guineas for his miniatures, placing his prices on par with leading oil portraitists such as Thomas Gainsborough, who sold half-length portraits for thirty guineas, and not far below Sir Joshua Reynolds, whose half-lengths commanded fifty guineas. William Daniell (1769–1837), an artist who knew and worked adjacent to John Smart in India, communicated Smart’s rates to Joseph Farington, who noted them in his diary of July 1798. See The Diary of Joseph Farington, ed. Kenneth Garlick and Angus MacIntyre (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), 3:1040. For Thomas Gainsborough’s prices, including his thoughts on framing, see Jacob Simon, “Thomas Gainsborough and Picture Framing,” National Portrait Gallery, London, March 8, 2003, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/programmes/the-art-of-the-picture-frame/artist-gainsborough. The distinction may therefore have less to do with the costs associated with each medium and more to do with their perceived prestige and purpose. Miniatures, with their intimate scale and often personal nature, afforded both patrons and artists a greater degree of creative flexibility. The private function of miniatures may have encouraged subtle experimentation with unconventional details, such as pink hair, without risking the scrutiny associated with more public-facing oil portraits.

The contrast between what one would typically expect to be the understated members of the clergy and the embellished military officers of the time adds further complexity to the matter. A satirical period account describes military men adorned with “a compound of flash and cockade, cosmetic, pink powder, with curls carronade” (barrel curls named after a small cannon called a carronade), reinforcing the idea of pink hair powder as a tool of display even in military circles.12Charles Morris or William Hewerdine, “Humbug Club Constitutional Song,” in Hilaria: The Festive Board (London: Printed for the author, 1798), 43. The “flash and cockade” of military uniforms came at the individual’s own expense. In an era where military titles were often purchased by families and part of a complicated demonstration of class and hierarchy, one’s cultivated appearance was inextricably tied up within this construction of identity.13For more on military dress in Smart’s oeuvre, see Maggie Keenan, “Dressing Smart: The Military Portraits of John Smart and John Smart Junior.” Smart’s portrait of Colonel James Hamilton (Fig. 8) depicts a figure with pink hair, although he appears in Smart’s preparatory sketch with more naturally colored hair (Fig. 9). Smart often inscribed the verso: Back or reverse side of a double-sided object, such as a drawing or miniature. of these preparatory sketches with color notes so that he could recall them later when making finished miniatures on ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures.. The reverse of this drawing reads, “Col. Hamilton / no. 3 Leicester Street / Leicester Fields / Dark Blue coat and / Waistcoat,” with no mention of hair color, leaving unresolved the reasons for the change from brown to pink.

Pink Hair in Smart’s Works

There are eleven pink-haired sitters in the Nelson-Atkins collection of works by Smart, and Starr Research Assistant Maggie Keenan has identified a total of forty-six such sitters spanning his career.14I am extremely grateful to Maggie Keenan for producing and sharing this dataset, culled from multiple searches across public and private collections and sales records. The information exists as a spreadsheet in NAMA’s curatorial files. Smart depicted pink-haired sitters as early as 1770, with the majority appearing between 1784 and 1785, the year he left for India. Variations in shade appear from gray-pink to lilac, and while men, women, Whigs, Tories, and military figures are represented, no single category predominates. Despite the lack of a clear pattern among the political, professional, or stylistic categories of pink-haired sitters, an interesting social and cultural connection emerges when considering Smart’s network and the exchanges between Britain and India.15For more on Smart’s tenure in India and the conscious network he built in London to facilitate important commissions in India, see Blythe Sobol, “Colonialism in Miniature: John Smart in India, 1785–1795.”

The prevalence of pink hair among his clientele—a group largely composed of merchants, military officers, and expatriates—suggests its association with a flamboyant, new-money aesthetic rather than the restrained decorum of the landed aristocracy or royal circles. These individuals, many of whom were shaped by the wealth derived from trade, commerce, and military service, navigated an evolving social landscape where visible markers of affluence and fashion were essential to their self-presentation. India, with its promise of economic opportunity through the Honourable East India Company (HEIC): A British joint-stock company founded in 1600 to trade in the Indian Ocean region. The company accounted for half the world’s trade from the 1750s to the early 1800s, including items such as cotton, silk, opium, and spices. It later expanded to control large parts of the Indian subcontinent by exercising military and administrative power., was particularly linked to the nouveaux riches, who capitalized on colonial ventures to amass wealth. The blending of European affluence with the vibrant colors of luxury goods in India created a backdrop where trends like powdered pink hair could flourish.16In a publication recounting British social life in India, the author describes how from the mid-1750s in India, “even visitors fresh from the raffish extravagance of London commented on the gaudy ostentation of the ladies’ diamonds and on the extraordinary colours and designs of their dresses. Not only the dresses of the ladies, for the ‘gay India coats’ of the Madras gentlemen startled their friends in England.” See Dennis Kincaid, British Social Life in India, 1608–1937 (London: George Routledge and Son, 1938), 69–70.

The Burnaby sisters, Georgiana Grace (see Fig. 7), Charlotte, and Harriet Emma,17See John Smart, Portrait of Mrs. John Richardson, née Harriet Emma Burnaby, 1794, watercolor on ivory, oval, 3 in. (7.6 cm.) high, sold at Christie’s, London, November 28, 2012, lot 402, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5628539. exemplify this intersection of English and colonial cultures. Daughters of a distinguished military officer, the Burnaby sisters married men of high rank in the HEIC and Madras Native Infantry.18Cy Harrison, “Sir William Burnaby (1st Baronet Burnaby of Broughton Hall),” Three Decks, accessed October 1, 2024, https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_crewman&id=168, cited in this volume. Although there is no direct evidence that their use of pink powder was specifically tied to their time in India, their portraits exemplify how English expatriates in colonial contexts adopted and adapted global aesthetic styles. The presence of French hairdressers active in India during this period further suggests the blending of international influences that likely reached and shaped Smart’s circle of clients.19The author of British Social Life in India recounts how, in India, after the midday meal, everyone slept until the evening, when the French hairdressers returned to “powder and trim” everyone’s hair. Kincaid noted that “The two most fashionable hairdressers were Frenchmen, and their charges were fantastically high: eight rupees for a gentleman’s hair-cut and four rupees for hairdressing.” See Kincaid, British Social Life in India, 88.

Smart’s use of pink hair in these portraits reflects broader

cultural movements in which status and fashion became

increasingly intertwined. By the end of the century, powdered

hair and wigs had become so widespread that, in 1795, the

British Parliament introduced a tax on hair powder to fund the

Revolutionary War with the American colonies and the

Napoleonic Wars: A series of major global

conflicts fought during Napoleon Bonaparte’s imperial rule

over France, from 1805 to 1815.

with France. Certain people were exempt: the royal family and

their servants, clergymen with incomes under one hundred

pounds, and members of the armed forces.20William Pitt introduced the Duty on Hair Powder Act on

May 5, 1795, as an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain.

The act was repealed in 1869. Stephen Dowell, A History of Taxation and Taxes in England from the

Earliest Times to the Year 1885 (London: Longmans, Green, 1888), 3:255–59.

Those who fell outside these groups could purchase a

certificate for one guinea from their local stamp office. In

its first year, the tax raised two hundred thousand

pounds.21“Hair Powder Certificates,” ref. QS/16,* *National

Archives, Kew, accessed August 8, 2024,

https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk

Smart’s pink-haired clientele was not an isolated phenomenon.

Other miniaturists in his orbit—including Robert Bowyer (ca.

1758–1834), Samuel Andrews (Irish, ca. 1767–1807), and

William Wood (1769–1809)—also depicted sitters with pink hair. Bowyer trained with

Smart in the late 1770s and later collaborated with him and

Robert Smirke (1752–1845) on commemorative prints of naval

officers in the 1790s, indicating that the artists shared an

understanding of materials and technique.22The National Gallery’s listing of portraits of John Smart

includes (under Doubtful Portraits) “the figure of Carmine

in Robert Smirke’s painting from The Conquest,”

exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1796 (no. 94). See

Arthur Jaffé, “John Smart, Miniature Painter,

1741(?)–1811: His Life and Iconography,”

Art Quarterly 17 (1954): 250, 254, figs. 11–12,

cited in “Mid-Georgian Portraits Catalogue / John Smart,

1741–1811, Miniature Painter / All known portraits,”

National Portrait Gallery, London, accessed November 13,

2024,

https://www.npg.org.uk

Beyond Smart’s immediate circle, other miniaturists, including Henry Jacob Burch (1763–after 1834), Sampson Towgood Roch (Irish, ca. 1757–1847), and George Engleheart (1750–1829) also depicted pink-haired sitters, further substantiating that the trend extended beyond Smart. This shared phenomenon could reflect a broader cultural style, while also highlighting the interconnected network of artists and sitters, many of whom overlapped in clientele and artistic approach.

Multiple factors could account for the prevalence of pink hair in these works. In a commissioned portrait, pink hair might reflect the artist’s aesthetic choice, the sitter’s personal style, or, as discussed, a faithful representation of the powdered wigs and experimental hair colors of the time. Alternatively, it could result from the unintended consequence of material degradation, such as pigment alteration or color fade. The complex interplay between these factors reflects both the cultural context and the technical realities of portraiture during this period.

Pink Hair and Fugitive Pigments

Artists such as Bowyer, Smirke, Andrews, and Wood worked directly with Smart and were familiar with his materials and methods. Other miniaturists who depicted pink-haired sitters, including Burch, Roch, and Engleheart, were undoubtedly aware of period treatises on painting miniatures. Robert Dossie’s Handmaid to the Arts (published in 1758 and reprinted in 1764, 1790, and 1796) and John Payne’s The Art of Painting in Miniature on Ivory (first published in 1797) provided detailed instructions for creating hair colors using a mix of pigments.24Robert Dossie, The Handmaid to the Arts (London: J. Nourse, 1758); John Payne, The Art of Painting in Miniature, on Ivory (London: Robert Laurie and James Whittle, 1797). For example, to create brown hair, an artist could mix the three primary colors (red, yellow, and blue) in equal amounts, or two complementary colors like red and green, orange and blue, or yellow and purple. Black and red could also be combined for a similar effect.

However, many pigments were prone to instability. Organic lake pigments were created by combining a dye with a metallic salt to create rich colors that did not dissolve in water but were susceptible to fading when exposed to light. Indigo, a dark blue derived from plants native to India, Java, and Peru, served as both a lake pigment and a water-soluble dye. Logwood, a red dye from the small redwood tree, could be prepared as a lake pigment that ranges from dark blue to black. Similarly, sap green (or bladder green), extracted from the juice of unripened buckthorn berries and sold in pig bladders, was a common yet unstable lake pigment.25For the pigment derived from ripened buckthorn berries, known as “Dutch pink,” see n. 2 and George O’Hanson, “When Pink was a Yellow Color,” Artist Materials Advisor blog, Natural Pigments, August 2, 2014, https://www.naturalpigments.com/artist-materials/pink-was-yellow-paint. See also Pierre François Tingry, The Painter and Varnisher’s Guide (London: G. Kearsley and J. Taylor, 1804), 363–67. Other pigments could also change under certain chemical conditions. Litmus blue, a dye obtained from plants (often used as an experiment today in entry-level science classes), can turn blue in alkaline solutions and red in acidic ones, making it prone to color shifts.26Dossie, Handmaid to the Arts, 89. Prussian blue, a synthetic pigment composed of ferric ferrocyanide, can turn gray in the presence of alkalis and sometimes lacked lightfastness.27Paintings conservator Jo Kirby has noted that the Prussian blue Gainsborough and other eighteenth-century artists used in their skies has faded over time, leaving behind a grayish appearance. See Jo Kirby, “Fading and Colour Change of Prussian Blue: Occurrences and Early Reports,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 14 (1993): 66, 69n38. Payne noted these instabilities, warning artists about sap green’s tendency to fade and burnt umber’s propensity to shift toward reddish-pink hues over time.28Payne, Art of Painting in Miniature, on Ivory, 21–22.

These pigment instabilities potentially impacted Smart’s miniatures and are also observed in other artists’ works. For example, a portrait of a man by Peter Paillou (English, 1757–1831) depicts green hair, possibly the result of burnt umber shifting to green over time (Fig. 10). Similarly, a miniature of Louis XV in the style of Jean-Baptise Massé (French, 1687–1767) provides clear evidence of unstable blue pigments in the hair and sky, both of which have turned pink (Fig. 11).29My thanks to Bernd Pappe for sharing this example. These examples suggest that pigment alteration might explain some of the pink and lilac tints present in Smart’s sitters’ hair.

To investigate this phenomenon, the Nelson-Atkins has undertaken technical analysis of four examples of Smart’s pink-haired sitters, realized at different points in his career: Portrait of a Man, 1773 (F65-41/11); Portrait of a Man, 1778 (F65-41/19); Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787 (F65-41/28); and Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798 (F65-41/39). With support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation’s endowment for scientific research, conservators employed techniques such as Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR): A broadly applicable microanalysis method for the identification of paint media classes such as oils, polysaccharides (gum arabic, etc.), proteins (glue and casein tempera), waxes (medium additions and restoration treatments), resins (varnish components), and synthetic media (restoration acrylics). FTIR is also very important for identifying pigments and fillers, and for differentiating closely related compounds (e.g. neutral and basic lead carbonates, both of which may be found in lead white). optimization, hyperspectral imaging (HSI) experimentation in the infrared part of the spectrum, microscopy, Raman spectroscopy: A microanalytical technique applicable primarily to pigments and minerals, differentiating them based on both chemical bonding and crystal structure, often with extremely high sensitivity for individual particles. For example, traditional indigo and synthetic phthalocyanine blue are both carbon compounds not well differentiated by other methods utilized here, especially when used dilutely. However, they give unique Raman spectra. Calcium carbonates derived from chalk or pulverized oyster shell of identical chemical compositions can be differentiated based on their crystal structures (calcite and aragonite, respectively)., polarized light microscopy (PLM): A method used for the study and differentiation of pigments based on the optical properties of individual particles, including color, refractive index, birefringence, etc. PLM is particularly useful in identifying the presence of organic pigments such as indigo and Prussian blue, which often cannot be differentiated from paint medium in the scanning electron microscopy (SEM); differentiating synthetic pigments from their natural analogs by particle shape or the presence of extraneous mineral matter; and disclosing the presence of pigments with similar composition but differing color, such as red and yellow iron oxides., and scanning electron microscopy (SEM): Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. This becomes increasingly important with the painting materials introduced in the early modern era, which are finer and more diverse than traditional artists’ materials. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an x-ray spectrometer, so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting.-based elemental analysis.

Analysis revealed stable mercury-based vermilion pigment in the face of the Portrait of a Man (1778), contributing to the sitter’s ruddy appearance.30See John Twilley and Stephanie Spence, technical report for John Smart, Portrait of a Man (F65-41/19), https://nelson-atkins.org/starr/contents/Volume-4/John-Smart/Early-London/F65-41-19/. However, the pink hues observed in his and other sitters’ hair were more complex. Smart used iron-based pigments, such as iron oxide, which are stable but can shift in color over time depending on environmental factors. If combined with a dye to create a more natural hair color, the fading of the dye could leave a pinkish hue. This pinking effect—alongside documented shifts in organic dyes—suggests a possible interplay between intended and unintended outcomes. Some of Smart’s pink- or lilac-haired portraits—such as the 1787 Portrait of Charlotte Porcher and the earlier Portrait of a Man (1773) may indicate intentional stylistic choices. Others, like the 1798 portrait of the possible cheesemonger’s wife, Mrs. Ronalds, with its pink-tinged background sky—may suggest color alterations similar to that seen in the miniature of Louis XV.

Smart’s renowned precision suggests that he would not have knowingly used unstable pigments.31For more on Smart’s reputation for precision, see DeGalan, “Painter of the People.” John Smart was an artist who painted what he saw. He was not prone to embellish his sitter’s appearance nor to shy away from painting signs of age, scars, moles, different-colored eyes, etc. However, the unpredictability of many of these materials and their vulnerability to environmental factors, such as internal relative humidity, leave open the possibility of long-term results he could not have predicted. While Mellon scientist John Twilley found no evidence in the four miniatures tested of aluminum-based lake pigments, nor of lake pigments precipitated on any other compound strongly indicative of fugitive pigments, he notes that soluble organic dyes in yellow, green, or brown may have been used alongside lake pigments to produce more natural hair colors, and they would be challenging to detect.32See, for example, Twilley and Spence, technical report for Portrait of a Man (F65-41/19), https://nelson-atkins.org/starr/contents/Volume-4/John-Smart/Early-London/F65-41-19/.

Conclusion

The prevalence of pink hair in Smart’s miniatures reflects a complex intersection of social, artistic, and technical factors. While not embraced by the English aristocracy, pink powder became a marker of the nouveaux riches—merchants, military officers, and expatriates—who used fashion to signal their rising status and social ambition. The private, intimate nature of portrait miniatures, which could be subtly bold without the scrutiny of public portraits, allowed for experimentation with unconventional trends like pink hair. These portraits also reflect the broader cultural exchanges of the time, including influences from colonial wealth and India, but ultimately, the trend emerged as part of a broader exploration of identity, social mobility, and artistic flexibility. Combined with the technical effects of aging pigments, the pink hair in Smart’s miniatures is a fascinating symbol of a dynamic period in both fashion and portraiture.

Notes

-

For more on Smart’s father and his profession, see Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Painter of the People: John Smart in London, 1741–1785.”

-

Curiously, some have questioned whether “pink powder” might refer to pigments like Dutch pink, a yellowish hue derived from ripened buckthorn berries. While Dutch pink was commonly used in artistic contexts, particularly for its soft, muted tones, period references to “pink powder” seem to align more consistently with the modern understanding of pink—brighter, more vivacious, and often associated with the fashion-forward circles of the time. This contrast suggests that Dutch pink was probably not the source for the hair powder referred to in fashion and literary references, a conclusion supported by its lack of appearance in recipe books for hair powder or blush during the period. It does not appear, for example, in the recipes for any type of face paint in Pierre-Joseph Buc’hoz, The Toilet of Flora: Or, a Collection of the Most Simple and Approved Methods of Preparing Baths, Essences, Pomatums, Powders, Perfumes, and Sweet-Scented Waters, With Receipts for Cosmetics of Every Kind. . . . rev. ed. (London: J. Murray and W. Nicoll, 1784). For Dutch pink’s applications in painting, see n. 25.

-

“Berwick of London,” Bath Chronicle, January 1, 1778.

-

See, for example, François Boucher, Pompadour at Her Toilette, 1750, with later additions, oil on canvas, 31 15/16 x 25 9/16 in. (81.2 x 64.9 cm), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge, MA, 1966.47, https://hvrd.art/o/303561. The painting is a vivid celebration of pink, reflecting its connection to both cosmetics and high fashion.

-

Marie Antoinette was also strongly associated with colored hair powder. Period accounts note that she wore Rose Maréchale powder, which perfumers touted as heightening the complexion. See [George Smith and William Makepeace Thackeray, eds.], “Paint, Powder, and Patches,” Cornhill Magazine 7 (June 1863): 739.

-

While Fox eventually stopped wearing blue hair powder, the color became associated with his Whig party politics; see Philopatris Varvicensis [Samuel Parr], Characters of the Late Charles James Fox (London: J. Mawman and Poultry, 1809), 1:111. Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, criticized his display and affectation of French fashions as unpatriotic; see Georgiana Spencer Cavendish, The Sylph: A Novel, ed. Jonathan Gross (1779; repr. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2007), xix.

-

Agnes Maria Bennett, Anna, or Memoirs of a Welch Heiress, Interspersed with Anecdotes of a Nabob (London: William Lane, 1785), 2:54–55.

-

See the essay for lot 22, A Life’s Devotion: The Collection of the Late Mrs T.S. Eliot (London: Christie’s, November 20, 2013), https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5733065.

-

“Another, who here on a Sunday does duty/ Sometimes, and is thought by himself a great beauty;/ In the service each word rises louder and louder, / ‘Till he’ave turn’d round, why? to see his pink powder, / With his little starch’d band, and an u-ly p-g face, / He thinks himself doubtless, the king of the place.” “Mrs. P—g, to Miss Nancy S—ds,” in X. Y., Cheltenham: A Fragment, with Explanatory Notes (London: G. Robinson and S. Harward, 1780), 12.

-

Amelia F. Rauser, “Hair, Authenticity, and the Self-Made Macaroni,” Eighteenth-Century Studies 38, no. 1 (October 2004): 101. See, for example, Matthew Darly and Mary Darly, The Original Macaroni, 1772, hand-colored etching on laid paper, sheet: 8 5/8 x 5 9/16 in. (21.9 x 14.1 cm), plate: 7 x 5 in. (17.8 x 12.7 cm), Colonial Williamsburg, https://emuseum.history.org/objects/12336/the-original-macaroni.

-

By 1798, Smart charged twenty-five guineas for his miniatures, placing his prices on par with leading oil portraitists such as Thomas Gainsborough, who sold half-length portraits for thirty guineas, and not far below Sir Joshua Reynolds, whose half-lengths commanded fifty guineas. William Daniell (1769–1837), an artist who knew and worked adjacent to John Smart in India, communicated Smart’s rates to Joseph Farington, who noted them in his diary of July 1798. See The Diary of Joseph Farington, ed. Kenneth Garlick and Angus MacIntyre (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), 3:1040. For Thomas Gainsborough’s prices, including his thoughts on framing, see Jacob Simon, “Thomas Gainsborough and Picture Framing,” National Portrait Gallery, London, March 8, 2003, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/research/programmes/the-art-of-the-picture-frame/artist-gainsborough.

-

Charles Morris or William Hewerdine, “Humbug Club Constitutional Song,” in Hilaria: The Festive Board (London: Printed for the author, 1798), 43.

-

For more on military dress in Smart’s oeuvre, see Maggie Keenan, “Dressing Smart: The Military Portraits of John Smart and John Smart Junior.”

-

I am extremely grateful to Maggie Keenan for producing and sharing this dataset, culled from multiple searches across public and private collections and sales records. The information exists as a spreadsheet in NAMA’s curatorial files.

-

For more on Smart’s tenure in India and the conscious network he built in London to facilitate important commissions in India, see Blythe Sobol, “Colonialism in Miniature: John Smart in India, 1785–1795.”

-

In a publication recounting British social life in India, the author describes how from the mid-1750s in India, “even visitors fresh from the raffish extravagance of London commented on the gaudy ostentation of the ladies’ diamonds and on the extraordinary colours and designs of their dresses. Not only the dresses of the ladies, for the ‘gay India coats’ of the Madras gentlemen startled their friends in England.” See Dennis Kincaid, British Social Life in India, 1608–1937 (London: George Routledge and Son, 1938), 69–70.

-

See John Smart, Portrait of Mrs. John Richardson, née Harriet Emma Burnaby, 1794, watercolor on ivory, oval, 3 in. (7.6 cm.) high, sold at Christie’s, London, November 28, 2012, lot 402, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-5628539.

-

Cy Harrison, “Sir William Burnaby (1st Baronet Burnaby of Broughton Hall),” Three Decks, accessed October 1, 2024, https://threedecks.org/index.php?display_type=show_crewman&id=168, cited in this volume.

-

The author of British Social Life in India recounts how, in India, after the midday meal, everyone slept until the evening, when the French hairdressers returned to “powder and trim” everyone’s hair. Kincaid noted that “The two most fashionable hairdressers were Frenchmen, and their charges were fantastically high: eight rupees for a gentleman’s hair-cut and four rupees for hairdressing.” See Kincaid, British Social Life in India, 88.

-

William Pitt introduced the Duty on Hair Powder Act on May 5, 1795, as an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The act was repealed in 1869. Stephen Dowell, A History of Taxation and Taxes in England from the Earliest Times to the Year 1885 (London: Longmans, Green, 1888), 3:255–59.

-

“Hair Powder Certificates,” ref. QS/16, National Archives, Kew, accessed August 8, 2024, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/ad3dafbb-cc41-49b7-ba0c-e21ecdaec5e0.

-

The National Gallery’s listing of portraits of John Smart includes (under Doubtful Portraits) “the figure of Carmine in Robert Smirke’s painting from The Conquest,” exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1796 (no. 94). See Arthur Jaffé, “John Smart, Miniature Painter, 1741(?)–1811: His Life and Iconography,” Art Quarterly 17 (1954): 250, 254, figs. 11–12, cited in “Mid-Georgian Portraits Catalogue / John Smart, 1741–1811, Miniature Painter / All known portraits,” National Portrait Gallery, London, accessed November 13, 2024, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/personExtended/mp04134/john-smart?tab=iconography.

-

Alan Derbyshire, “The William Wood Manuscripts,” in Bernd Pappe and Juliane Schmieglitz-Otten, eds., Portrait Miniatures: Artists, Functions, Techniques, and Collections (proceedings from the fourth conference) (Petersberg, Germany: Michael Imhof, in association with the Tansey Miniatures Foundation, 2023), 162–71.

-

Robert Dossie, The Handmaid to the Arts (London: J. Nourse, 1758); John Payne, The Art of Painting in Miniature, on Ivory (London: Robert Laurie and James Whittle, 1797).

-

For the pigment derived from ripened buckthorn berries, known as “Dutch pink,” see n. 2 and George O’Hanson, “When Pink was a Yellow Color,” Artist Materials Advisor blog, Natural Pigments, August 2, 2014, https://www.naturalpigments.com/artist-materials/pink-was-yellow-paint. See also Pierre François Tingry, The Painter and Varnisher’s Guide (London: G. Kearsley and J. Taylor, 1804), 363–67.

-

Dossie, Handmaid to the Arts, 89.

-

Paintings conservator Jo Kirby has noted that the Prussian blue Gainsborough and other eighteenth-century artists used in their skies has faded over time, leaving behind a grayish appearance. See Jo Kirby, “Fading and Colour Change of Prussian Blue: Occurrences and Early Reports,” National Gallery Technical Bulletin 14 (1993): 66, 69n38.

-

Payne, Art of Painting in Miniature, on Ivory, 21–22.

-

My thanks to Bernd Pappe for sharing this example.

-

See John Twilley and Stephanie Spence, technical report for John Smart, Portrait of a Man (F65-41/19), https://nelson-atkins.org/starr/contents/Volume-4/John-Smart/Early-London/F65-41-19/.

-

For more on Smart’s reputation for precision, see DeGalan, “Painter of the People.” John Smart was an artist who painted what he saw. He was not prone to embellish his sitter’s appearance nor to shy away from painting signs of age, scars, moles, different-colored eyes, etc.

-

See, for example, Twilley and Spence, technical report for Portrait of a Man (F65-41/19).

doi: 10.37764/8322.6.94