Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “John Smart, Portrait of John Holland, Governor of Madras, 1806,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1630.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “John Smart, Portrait of John Holland, Governor of Madras, 1806,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1630.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

John Holland, born on August 29, 1744, in Fort St. George, Madras, India, was one of four sons of John and Sophia (Fowke) Holland.1The name Holland also appears as “Hollond” in various period sources. However, in his will, it is clearly Holland; Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, series PROB 11, class PROB 11, ref. 1451, National Archives, Kew. He steadily advanced through the ranks of the Honourable East India Company (HEIC): A British joint-stock company founded in 1600 to trade in the Indian Ocean region. The company accounted for half the world’s trade from the 1750s to the early 1800s, including items such as cotton, silk, opium, and spices. It later expanded to control large parts of the Indian subcontinent by exercising military and administrative power., beginning as a writer, or clerk, and rising to positions of factor (1774), junior merchant (1778), senior merchant (1780), and finally governor of Madras from February 7, 1789, to February 13, 1790.2Charles Prinsep, A List of the Services of Madras Civil Servants from 1740 to 1858 (London: Truebner, 1885), transcribed by Marianne Mansfield, July 2010, Families in British India Society, https://search.fibis.org/bin/aps_detail.php?id=884084. John Hollond made £5.18.10 as a writer and was promoted to factor on May 21, 1766. See John Call, “Account of Salary due to H. C. Servants from 25th March to 25th September 1766 for the Madras Presidency,” September 25, 1766, transcribed by Peter Bailey, July 5, 2008, Families in British India Society, https://search.fibis.org/bin/aps_detail.php?id=2715248. His governorship marked the peak of his career, during which he and his younger brother Edward, who succeeded him as governor for a brief week (February 13–20, 1790), engaged in extensive corruption.

The Holland brothers, notorious for their greed, amassed considerable wealth during their tenure. They were aided in their corrupt practices by Avadhanam Paupiah, a dubash (translator) who became the most influential Indian in the Madras presidency.3The Madras Presidency was a British trading post and administrative area in India that expanded through wars and alliances. The head of the Madras Presidency was called the governor, assisted by a council. For more information, see C. D. Maclean, Standing Information Regarding the Official Administration of Madras Presidency, Government of Madras, 2nd ed. (Madras: Government Press, 1879). Even the Nawab of Arcot had to go through Paupiah to reach the governor. Paupiah’s influence and the Hollands’ corruption reached a tipping point when they clashed with David Haliburton, a member of the HEIC’s Board of Revenue, who sought to expose their wrongdoing. To silence Haliburton, the Hollands used Paupiah to forge evidence against him, leading to Haliburton’s forced removal from service.4Haliburton was exonerated. For more on David Haliburton, see Papers of David Haliburton, 1832, Royal Asiatic Society Archives, London, GB 891 DH.

However, the Hollands’ scheme unraveled when Lord Cornwallis, the governor-general of India, uncovered their corrupt practices. While John fled to France aboard the Pigot in June 1790, Edward returned to England as a prisoner aboard the Rodney in June 1791, and he was fined substantially.5As reported in the Kentish Gazette, June 17, 1791: “Mr. Edward Holland is by this time arrived in London from on board the Rodney; one of Lord Kenyon’s tipstaffs having been dispatched with his Lordship’s warrant for that purpose. The charge against him is said to be, not having accounted for cash to the amount of 100,000l. received from the Nawab of Arcot on the Company’s account; he will, however, doubtless, procure sufficient bail.” The author continues, “Mr. John Holland, late Governor of Madras, with his family, are set out for Paris, on account of some particular news, it is said, he has received from India by the Rodney, which renders his attendance on the Continent necessary.” Paupiah, left to face the consequences in India,6Paupiah was tried in July 1792 for conspiracy against Haliburton in the Court of Quarter Sessions, presided over by Charles Meadows. See Avadaunum Paupiah and David Haliburton, The Trial of Avadaunum Paupiah Bramin (London: J. Murray, 1793). was found guilty at trial in 1792 and sentenced to three years in prison, along with a significant fine, marking one of the most notorious criminal prosecutions of the era.7C. S. Srinivasachari notes that the story of Paupiah and the Hollands appears in Sir Walter Scott’s novel, The Surgeon’s Daughter (1827). Scott was related to the Haliburtons through his paternal grandmother and likely came across a copy of the pamphlet The Trial of Avadhanam Paupiah, published by Haliburton in 1793 (see n. 6). In The Surgeon’s Daughter, Scott portrays Paupiah as the dubash through whom the president of the council primarily communicated with the native courts. Scott depicts Paupiah as an “artful Hindu,” a “master counsellor of dark projects, an Oriental Machiavel, whose premature wrinkles were the result of many an intrigue, in which the existence of the poor, the happiness of the rich, the honour of men, and the chastity of women, had been sacrificed without scruple, to attain some private or political advantage.” See Walter Scott, The Surgeon’s Daughter (1827; Project Gutenberg e-book released September 2004; last updated February 27, 2018) chapter 12, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6428/6428-h/6428-h.htm#link2HCH0012. See also C. S. Srinivasachari, History of the City of Madras: Compiled for the Tercentenary Celebration Committee, 1939 (Madras: P. Varadachary, 1939), 197–99.

John Holland remained in France, where he lived with Mary Bint of Lambourn, Berkshire.8Mary Bint was baptized April 20, 1765. I am grateful to Maggie Keenan, Starr Research Assistant, who helped decode Holland’s will to read “Bint” (not Bent), and who subsequently found Mary Bint’s genealogy records. “Mary Bint baptismal certificate,” April 20, 1765, England, Select Births and Christenings, FHL film number: 251838. She was initially described as a “dear friend” in his will of 1803, but by October of 1805, the document identified her as his wife.9John Holland married his first wife, Anne Henchman, and they had two sons that he named in his will. It was undocumented elsewhere that Holland took a second wife, Mary Bint; however, this too was revealed in his will, cited in n. 1. The ancestry record for Anne and John Holland’s marriage is for November 23, 1769. W. K. Firminger, E. W. Madge, and S. C. Sanial, “Marriages in Bengal, 1759–1779,” Registers at St. John’s Church, Calcutta (Calcutta: Calcutta Historical Society, 1920), 495, https://archive.org/details/bppbengal-marriages-images/mode/. Holland’s will, along with its many codicils increasing her annuity, serve as a testament to his affection and the care she provided him in his final years.10Holland specifically mentions that she gave him water when he was too weak to sip and other things that demonstrate his affection for her. He also defends her character to anyone reading the will—especially his children—indicating that she never asked for any money and that is a true test of her character. Although his will mentions several mourning rings to be left to individuals in his memory, there is no mention of a portrait miniature. Holland died on January 31, 1806, in Paris, age sixty-two.11As noted in his will, cited in n. 1.

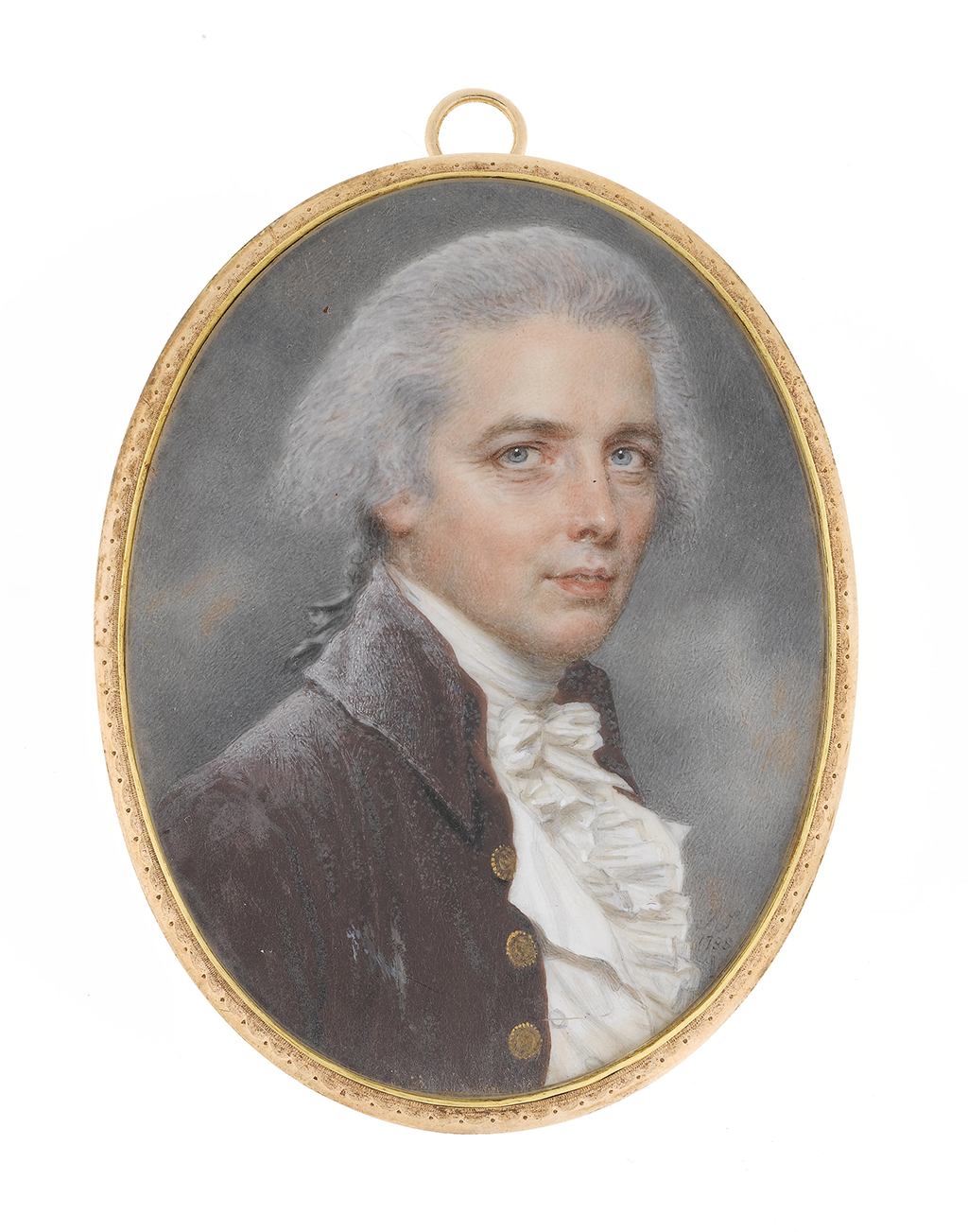

John Smart painted John Holland at least twice: once

in three-quarters view against a gray sky background

(Fig. 1),

signed 1788 on the

recto: Front or main side of a

double-sided object, such as a drawing or

miniature.

but inscribed 1795 on the

verso: Back or reverse side of a

double-sided object, such as a drawing or

miniature.

interior; and the present miniature, signed 1806 on

the recto but inscribed 1792 on the verso interior by

the artist. While the 1788 portrait is not

definitively identified as John Holland (only a member

of the “Hollond” family), the subject shares the same

piercing blue eyes and distinct mole on the left

bridge of his nose as the sitter in the Nelson-Atkins

miniature. Despite the eighteen-year gap between the

dates, the sitter appears to be a similar age in both

portraits, suggesting that Smart made preparatory

sketches of Holland in India in 1788 and later used

one to create the Nelson-Atkins portrait, possibly as

a posthumous image after Holland’s death in January

1806.12Incidentally, Smart painted a portrait of a Mrs.

Holland (Bridget Brown Holland, 1746–1826), in

1806, the same year as the Nelson-Atkins portrait.

Bridget’s husband was Henry Holland Jr.

(1745–1806), who died in 1806, the same year as

John Holland. However, given period imagery of

Henry Holland—including James Heath, after George

Chinnery, Henry Holland, late 18th

century, stipple engraving, 8 1/2 x 7 3/4 in.

(21.5 x 19.7 cm), National Portrait Gallery,

London,

https://www.npg.org.uk

In the Nelson-Atkins miniature, Smart presents Holland on a nearly four-inch piece of ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. in dramatic profile, revealing his distinctive mole and a powdered white hair styled in a cadogan: Hairstyle of a looped chignon, named after William Cadogan (the first Earl of Cadodgan, 1675–1726). It became a popular style among women and men, especially the “macaroni” (dandies) in the eighteenth century.,13For more on this hairstyle, its use, and history, see Mary Brooks Picken, A Dictionary of Costume and Fashion: Historic and Modern, 17th ed. (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1957), 32. which has left residue against the back of his dark brown coat. Holland appears in profile against a solid olive-brown background and a mauve swagger curtain—perhaps alluding to the grandeur of earlier court portraits by Sir Anthony Van Dyck (Flemish, 1599–1641) or the intense profile portraits by Hans Holbein the Younger (German, 1497/98–1543), which Smart admired and had his own son copy as part of his training. This allusion is fitting, given the dramatic and controversial life of the sitter. This is the only known portrait in which Smart presents a sitter in such a profile, outside of his own self-portrait, realized in 1793.

Although Holland was not yet governor of Madras in 1788 when Smart first painted him, his potential for the role had already been a topic of discussion as early as 1784, when he was offered the position but declined due to health issues.14“London, October 11, 1784,” Gazette de France, October 26, 1784, 354. Smart likely recognized the significance of Holland as a subject, understanding that such a commission could bolster his reputation as a leading portrait artist of his time. This miniature, with its refined execution and dramatic flair, captures not only the likeness of John Holland but also the complex legacy of a man whose life was marked by both ambition and infamy.

Notes

-

The name Holland also appears as “Hollond” in various period sources. However, in his will, it is clearly Holland; Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, series PROB 11, class PROB 11, ref. 1451, National Archives, Kew.

-

Charles Prinsep, A List of the Services of Madras Civil Servants from 1740 to 1858 (London: Truebner, 1885), transcribed by Marianne Mansfield, July 2010, Families in British India Society, https://search.fibis.org/bin/aps_detail.php?id=884084. John Hollond made £5.18.10 as a writer and was promoted to factor on May 21, 1766. See John Call, “Account of Salary due to H. C. Servants from 25th March to 25th September 1766 for the Madras Presidency,” September 25, 1766, transcribed by Peter Bailey, July 5, 2008, Families in British India Society, https://search.fibis.org/bin/aps_detail.php?id=2715248.

-

The Madras Presidency was a British trading post and administrative area in India that expanded through wars and alliances. The head of the Madras Presidency was called the governor, assisted by a council. For more information, see C. D. Maclean, Standing Information Regarding the Official Administration of Madras Presidency, Government of Madras, 2nd ed. (Madras: Government Press, 1879).

-

Haliburton was exonerated. For more on David Haliburton, see Papers of David Haliburton, 1832, Royal Asiatic Society Archives, London, GB 891 DH.

-

As reported in the Kentish Gazette, June 17, 1791: “Mr. Edward Holland is by this time arrived in London from on board the Rodney; one of Lord Kenyon’s tipstaffs having been dispatched with his Lordship’s warrant for that purpose. The charge against him is said to be, not having accounted for cash to the amount of 100,000l. received from the Nawab of Arcot on the Company’s account; he will, however, doubtless, procure sufficient bail.” The author continues, “Mr. John Holland, late Governor of Madras, with his family, are set out for Paris, on account of some particular news, it is said, he has received from India by the Rodney, which renders his attendance on the Continent necessary.”

-

Paupiah was tried in July 1792 for conspiracy against Haliburton in the Court of Quarter Sessions, presided over by Charles Meadows. See Avadaunum Paupiah and David Haliburton, The Trial of Avadaunum Paupiah Bramin (London: J. Murray, 1793).

-

C. S. Srinivasachari notes that the story of Paupiah and the Hollands appears in Sir Walter Scott’s novel, The Surgeon’s Daughter (1827). Scott was related to the Haliburtons through his paternal grandmother and likely came across a copy of the pamphlet The Trial of Avadhanam Paupiah, published by Haliburton in 1793 (see n. 6). In The Surgeon’s Daughter, Scott portrays Paupiah as the dubash through whom the president of the council primarily communicated with the native courts. Scott depicts Paupiah as an “artful Hindu,” a “master counsellor of dark projects, an Oriental Machiavel, whose premature wrinkles were the result of many an intrigue, in which the existence of the poor, the happiness of the rich, the honour of men, and the chastity of women, had been sacrificed without scruple, to attain some private or political advantage.” See Walter Scott, The Surgeon’s Daughter (1827; Project Gutenberg e-book released September 2004; last updated February 27, 2018) chapter 12, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/6428/6428-h/6428-h.htm#link2HCH0012. See also C. S. Srinivasachari, History of the City of Madras: Compiled for the Tercentenary Celebration Committee, 1939 (Madras: P. Varadachary, 1939), 197–99.

-

Mary Bint was baptized April 20, 1765. I am grateful to Maggie Keenan, Starr Research Assistant, who helped decode Holland’s will to read “Bint” (not Bent), and who subsequently found Mary Bint’s genealogy records. “Mary Bint baptismal certificate,” April 20, 1765, England, Select Births and Christenings, FHL film number: 251838.

-

John Holland married his first wife, Anne Henchman, and they had two sons that he named in his will. It was undocumented elsewhere that Holland took a second wife, Mary Bint; however, this too was revealed in his will, cited in n. 1. The ancestry record for Anne and John Holland’s marriage is for November 23, 1769. W. K. Firminger, E. W. Madge, and S. C. Sanial, “Marriages in Bengal, 1759–1779,” Registers at St. John’s Church, Calcutta (Calcutta: Calcutta Historical Society, 1920), 495, https://archive.org/details/bppbengal-marriages-images/mode/.

-

Holland specifically mentions that she gave him water when he was too weak to sip and other things that demonstrate his affection for her. He also defends her character to anyone reading the will—especially his children—indicating that she never asked for any money and that is a true test of her character.

As noted in his will, cited in n. 1.

-

Incidentally, Smart painted a portrait of a Mrs. Holland (Bridget Brown Holland, 1746–1826), in 1806, the same year as the Nelson-Atkins portrait. Bridget’s husband was Henry Holland Jr. (1745–1806), who died in 1806, the same year as John Holland. However, given period imagery of Henry Holland—including James Heath, after George Chinnery, Henry Holland, late 18th century, stipple engraving, 8 1/2 x 7 3/4 in. (21.5 x 19.7 cm), National Portrait Gallery, London, https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw192262/Henry-Holland—it is clear that Henry Holland bears no physical resemblance to the present sitter. Moreover, given the presence of the mole and the verso inscription in Smart’s hand identifying the Nelson-Atkins portrait as John Holland, Governor of Madras, the present author does not question the identity of the Nelson-Atkins picture and considers it a coincidence that Smart painted Mrs. Holland—a very common last name—in the same year. Mrs. Bridget Holland’s portrait was featured in Sotheby’s, London, “Silhouettes and Good English and Continental Portrait Miniatures,” December 11, 1978, lot 88.

-

For more on this hairstyle, its use, and history, see Mary Brooks Picken, A Dictionary of Costume and Fashion: Historic and Modern, 17th ed. (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1957), 32.

-

“London, October 11, 1784,” Gazette de France, October 26, 1784, 354.

Provenance

Charles William Dyson Perrins (1864-1958), Worcestershire, by 1929-1958 [1];

Purchased from his posthumous sale, Important English and Continental Miniatures and Fine Watches, Sotheby’s, London, December 11, 1958, lot 63, as A Young Man Called Mr. Holland, by Leggatt Brothers, London, probably on behalf of Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, 1958–1965 [2];

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Notes

[1] According to Basil Long, British Miniaturists (London: Holland Press, 1929), 407, “Mr. Dyson Perrins has several good miniatures by Smart. One, “Mr. Holland,” which is signed and dated 1806, is unusual in its pose: the sitter is in profile with his back to the spectator; a mauve curtain is seen. As this miniature seems to show a costume of an earlier date than 1806, it is perhaps a copy by Smart from another portrait.”

[2] The annotated catalogue for this sale is located at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, Miller Nichols Library. The annotations are most likely by Mr. or Mrs. Starr. Lot 63 is inscribed with “£360,” and next to the reproduction on the frontispiece, “by: John Smart.—£360. Leggatt.” Archival research indicates that the Starrs purchased many miniatures from Leggatt Brothers, either directly or with Leggatt acting as their purchasing agent.

Exhibitions

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Mr. Holland.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 139, as Mr. Holland.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of John Holland, Governor of Madras.

References

Basil Long, British Miniaturists (London: Holland Press, 1929), 407, as Mr. Holland.

Catalogue of Important English and Continental Miniatures and Fine Watches (London: Sotheby’s, December 11, 1958), 18, (repro.), as A Young Man Called Mr. Holland.

Daphne Foskett, John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (New York: October House, 1964), 68, pl. 27, (repro.), as Mr. Holland (called).

Daphne Foskett, “Miniatures by John Smart,” Antiques 90, no. 3 (September 1966): 357, (repro.), as Mr. Holland.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 139, p. 49, (repro.), as Mr. Holland.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.