Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “John Smart, Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1610.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “John Smart, Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1610.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

In 1798, John Smart painted this portrait of a woman known as “Mrs. Ronalds,” capturing her in three-quarters profile against a dramatic sky of gray, pink, and yellow hues. The sitter, dressed in a white empire-waist gown cinched with a blue ribbon, gazes at the viewer with soft brown eyes beneath heavy, kohl-darkened eyebrows. Her hair, likely powdered, has a subtle pink tint, possibly due to fugitive pigments: Fugitive pigments are not lightfast, which means they are not permanent. They can lighten, darken, or nearly disappear over time through exposure to environmental conditions such as sunlight, humidity, temperature, or even pollution. over time, a characteristic often seen in Smart’s miniatures.

Although pink hair powder did exist at the time, its presence in portraiture is limited to miniatures and predominantly found in portraits produced by John Smart and artists in his immediate circle, whose clientele was largely made up of the merchant and military classes.1For more on this phenomenon in Smart’s work, see Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair,” in this catalogue. Although technical analysis conducted as part of the research for this catalogue confirmed that Smart used red iron rather than a fading lake pigment: An organic pigment manufactured by precipitating a soluble, natural colorant onto a colorless or white, insoluble, inorganic substrate. Historically, natural colorants were extracted from plants and insects. The substrate is traditionally hydrated aluminum oxide, but other substrates such as chalk (calcium carbonate), clay, or gypsum (calcium sulphate) have also been used.—suggesting the pink was a deliberate choice—Mellon scientist John Twilley posits that Smart may also have employed organic dyes.2See the accompanying technical entry by John Twilley and Stephanie Spence. These water-soluble dyes could have been mixed with the iron to create a more naturalistic brownish hue of hair that has since faded.3See the accompanying technical entry by Twilley and Spence. This alteration could account for the pink tones in the hair, suggesting that the effect is not a deliberate fashion statement but rather the result of color change over time.4The study of John Smart’s palette was part of a Mellon Science Research project undertaken by John Twilley with the support of NAMA objects conservator Stephanie Spence. The research question grew out of the prevalence of pink hair among Smart’s sitters alongside the lack of pink hair among Smart’s contemporaries, other than those within his circle, in oil or miniature. This miniature was one of four examined as part of this discrete study, the results of which appear in the technical entry accompanying this curatorial entry. See also John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773, F65-41/11; Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; and Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787, F65-41/28.

Although the Ronalds name was rare in southern England, family historian Beverley Ronalds believes the sitter may be from her family line.5Beverley Ronalds to the author, August 20, 2024; related correspondence in NAMA curatorial files. Two potential candidates have emerged: Elizabeth Ronalds, née Clarke (1758–1823), who came from a middle-class family involved in the silk trade,6Beverly F. Ronalds, “An Ancestor’s Life seen through Her Recipe Book,” Women’s History: The Journal of the Women’s History Network 2, no. 17 (Spring 2021): 20, https://womenshistorynetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Spring21Online.pdf. and her sister-in-law Jane Ronalds, née Field (1766–1852).7I am grateful to Finn Miller, curatorial assistant, for his genealogical research assistance on the Ronalds family. Elizabeth married her cousin Hugh Ronalds on September 9, 1784, and they commissioned portrait miniatures around 1810. That known portrait of Elizabeth (Fig. 1) shows a woman with brilliant red hair and, most important, blue eyes, which do not align with the Nelson-Atkins sitter. Jane Ronalds, who married Hugh’s brother, Francis, was described as having darker features and remains a speculative possibility, though no definitive link can be made based on existing evidence (Fig. 2).

The Ronalds family was deeply embedded in London’s merchant class. Hugh Ronalds was a prominent nurseryman, supplying clients like the Clitherows of Boston Manor and the Dukes of Devonshire at Chiswick House,8See Val Bott, “Some Brentford Nursery Gardeners,” Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society Journal 17 (2008), https://brentfordandchiswicklhs.org.uk/some-brentford-nursery-gardeners. See also Beverly F. Ronalds, “Ronalds Nurserymen in Brentford and Beyond,” Garden History 45 (2017): 82–100; Hugh Ronalds, “Description of the Different Varieties of Brocoli [sic], with an Account of the Method of Cultivating Them,” Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London 3 (1820): 161–69. while his brother Francis worked as a cheesemonger.9For more on Francis Ronalds and his son Francis Ronalds Jr., who went on to become, according to Beverly Ronalds, the first electrical engineer ever, see Beverly Ronalds, “Ronalds, Francis,” January 14, 2017, Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography, accessed November 17, 2024, https://www.uudb.org/ronalds-francis. Both men and their wives moved within circles that would have appreciated the technical skill and honest depiction that Smart brought to his work.

In this portrait, Smart remains true to his reputation for capturing a sitter’s individuality, portraying Mrs. Ronalds with a cleft chin, dark, bushy eyebrows, and subtle undereye circles. While not a conventional beauty, she is presented with a quiet dignity, reflecting both her social standing and Smart’s masterful approach.

Notes

-

For more on this phenomenon in Smart’s work, see Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair, in this catalogue.”

-

See the accompanying technical entry by John Twilley and Stephanie Spence.

-

See the accompanying technical entry by Twilley and Spence.

-

The study of John Smart’s palette was part of a Mellon Science Research project undertaken by John Twilley with the support of NAMA objects conservator Stephanie Spence. The research question grew out of the prevalence of pink hair among Smart’s sitters alongside the lack of pink hair among Smart’s contemporaries, other than those within his circle, in oil or miniature. This miniature was one of four examined as part of this discrete study, the results of which appear in the technical entry accompanying this curatorial entry. See also John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1770, F65-41/11; Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; and Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787, F65-41/28.

-

Beverley Ronalds to the author, August 20, 2024; related correspondence in NAMA curatorial files.

-

Beverly F. Ronalds, “An Ancestor’s Life seen through Her Recipe Book,” Women’s History: The Journal of the Women’s History Network 2, no. 17 (Spring 2021): 20, https://womenshistorynetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Spring21Online.pdf.

-

I am grateful to Finn Miller, curatorial assistant, for his genealogical research assistance on the Ronalds family.

-

See Val Bott, “Some Brentford Nursery Gardeners,” Brentford and Chiswick Local History Society Journal 17 (2008): https://brentfordandchiswicklhs.org.uk/some-brentford-nursery-gardeners. See also Beverly F. Ronalds, “Ronalds Nurserymen in Brentford and Beyond,” Garden History 45 (2017): 82–100; Hugh Ronalds, “Description of the Different Varieties of Brocoli [sic], with an Account of the Method of Cultivating Them,” Transactions of the Horticultural Society of London 3 (1820): 161–69.

-

For more on Francis Ronalds and his son Francis Ronalds Jr., who went on to become, according to Beverly Ronalds, the first electrical engineer ever, see Beverly Ronalds, “Ronalds, Francis,” January 14, 2017, Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography, accessed November 17, 2024, https://www.uudb.org/ronalds-francis.

Technical Entry

Citation

Chicago:

Stephanie Spence and John Twilley, “John Smart, Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798,” technical entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1610.

MLA:

Spence, Stephanie, and John Twilley. “John Smart, Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds, 1798,” technical entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1610.

This oval portrait depicts Mrs. Ronalds in three-quarter view wearing a white dress with a blue sash set against a pale sunset sky. At approximately three inches in height, it was completed in 1798 on the larger-format ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. support that became common near the end of Smart’s career. Mrs. Ronalds is of fair complexion with rosy cheeks, dark brows, brown eyes, and a cleft chin. Her portrait relies heavily on the brightness of the reflective ivory in the light passages of the dress and facial features. The colored passages are rendered with extremely thin paint in overlapping hatched: A technique using closely spaced parallel lines to create a shaded effect. When lines are placed at an angle to one another, the technique is called cross-hatching. and stippling: Producing a gradation of light and shade by drawing or painting small points, larger dots, or longer strokes. applications to create this highly realistic portrait. The portrait is signed “J.S./1798” in the lower right.

The unusual pink color of Mrs. Ronalds’ hair is shared with eleven other sitters in the Nelson-Atkins collection as well as others in his larger corpus of works.1See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair,” in this catalogue. Pink or lilac hair powder was uncommon in portraiture, with most subjects opting for white or grayish-white. However, Smart’s portraits of his merchant-class clientele reveal hints of pink and lilac hues, raising the question of whether this was a deliberate choice or the result of light-sensitive pigments fading over time, obscuring their original effect.

Pigment analysis and technical imaging were performed on four John Smart portraits with light pink or lilac-tinted hair, spanning a twenty-five-year period of his career, to explore the artist’s palette and working techniques beyond the means of visual examination.2See John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773, F65-41/11; Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; and Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787, F65-41/28., 3The scientific study of the four John Smart portraits via x-ray spectrometry and SEM analyses was carried out by John Twilley, Mellon Science Advisor, with support of an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. It is important to note that the very small scale and extreme thinness of the paint applications in portrait miniatures require that analysis be done to the extent possible through non-sampling means, such as x-ray fluorescence spectrometry elemental mapping (MA-XRF) or XRF elemental mapping: A non-destructive technique that entails collecting thousands of x-ray fluorescence spectra at regular intervals across a painting to build an alternate set of images depicting the locations and amounts of different elements. Although the information is fundamentally the same as measurements gathered from a single-point XRF, the graphical nature of the result is often a more powerful technique for understanding trends in an artist’s use of materials. The high number of spectra allows statistical manipulations of the elemental information to locate correlations between different pigments that would not be possible from a small number of tests. For example, the consistent occurrence of mercury along with chromium, and iron along with copper, could show that vermilion was used to mute the chrome green and red ocher was similarly employed in a mixture that includes emerald green. The resulting correlation maps then serve to show where the two cases occur in the composition. MA-XRF can also reveal preliminary paint applications that became covered as the composition was completed, thereby disclosing aspects of the painter’s method.. However, no single analytical method provides a complete pigment analysis. Instead, pigment identification requires that information from different scientific techniques be combined and interpreted. This includes microanalytical methods, like scanning electron microscopy/energy-dispersive x-ray spectrometry (SEM-EDS): A combined technique that uses a scanning electron microscope and energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy to analyze materials. Performed on a microsample of paint, the SEM provides a means of studying particle shapes beyond the magnification limits of the light microscope. The SEM is routinely used in conjunction with an x-ray spectrometer so that elemental identifications can be made selectively on the same minute scale as the electron beam producing the images. SEM methods are particularly valuable in studying unstable pigments, adverse interactions between incompatible pigments, and interactions between pigments and surrounding paint medium, all of which can have profound effects on the appearance of a painting., that provide powerful means of extracting information from minute samples as small as single particles that cannot be obtained by non-sampling methods. Technical imaging is a useful tool that can allow inferences to be drawn based on optical behaviors such as fluorescence: The reflected visible light produced when painting materials interact with ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not all materials fluoresce, but the color and intensity of the fluorescence is frequently used to differentiate between original and restoration materials, characterize the varnish layers, or reveal the distribution of pigments across the composition. Also known as ultraviolet (UV) fluorescence or UV-induced visible fluorescence. colors and can be used as a complementary method to analytical techniques.4Technical imaging employs technology to observe an object in wavelength ranges that extend beyond the capabilities of the human eye, from the ultraviolet (UV) to the near infrared (NIR). Images were captured using an UV-VIS-IR-modified Nikon D7000 DSLR camera with a 60mm lens and a set of UV-VIS-IR bandpass filters. The imaging set included ultraviolet illumination (UVL), reflected infrared (IR), reflected ultraviolet (RUV), visible-induced visible luminescence (VIVL), false-color UV (FCUV), and false-color IR (FCIR). These imaging techniques can be used to make tentative identifications of artist’s materials and pigments and visualize restoration materials, such as inpainting, varnish coatings, and materials not readily visible to the naked eye. Imaging is a means to examine the surface of an artwork and discover materials that require identification through scientific analysis. While these methods were used to find answers pertaining to the sitters’ hair color, they offered insights into the full compositions, revealing new information about John Smart’s palette and working techniques that were previously unknown.

Among the four portraits analyzed, the artist differentiated the means of painting based on the gender of the sitters. The female depictions, whose fair complexions rely more heavily on the whiteness and translucence of the ivory support, were more thinly painted than those of the males, whose ruddy complexions required the ivory to be more heavily painted. This difference extends to the representations of their clothing and becomes quite apparent in MA-XRF, where the response from the thin paint of the female portraits is weak and indicative of only the most abundant pigments. All portraits give strong maps for calcium and phosphorous, the two primary elements of bone, tooth enamel, and ivory. The phosphorous response is suppressed where the overlying paint absorbs some of its characteristic x-rays, giving a faint “negative” image of the sitter compared to the male sitters that have large areas of the phosphorous map blacked out where the heaviest paint applications have all but blocked the weaker x-rays.

Similarities have also been observed between Smart’s treatment of certain male and female sitters. The false-color infrared (FCIR): Images created through digital post-processing by combining and rearranging the color channels of visible and near-infrared images. In the visible image, the Red and Green channels are assigned to the Green and Blue channels respectively, while the infrared image is assigned to the Red channel. The false colors produced can aid in interpretation of media and materials present and inform further scientific analysis, conservation examination, and scholarly research. image presents similarities between the pigment composition of the hair for Mrs. Ronalds and Portrait of a Man, 1778 (F65-41/19). These portraits share the trait of light pink hair in visual examination and appear yellow in FCIR (see Fig. 3a, b). In contrast, the lilac-haired sitters Charlotte Porcher (F65-41/28) and Portrait of a Man, 1773 (F65-41/11) present as pink in their respective false-color images. This visual similarity in hair color has been demonstrated through elemental analysis to be based on similarity of pigment usage, where the yellow false-color responses of Mrs. Ronalds and the male sitter, painted twenty years apart, are indicative of the iron oxide pigments identified with MA-XRF.5The yellow tone in the FCIR image for this portrait is in part due to iron-based pigments in the mixture. This behavior—an aggregate or summed-response for all the ingredients that influence the false color appearance—exemplifies why technical imaging allows inferences to be drawn but is seldom sufficient to confirm or exclude the presence of a pigment. Antonino Cosentino, “Identification of Pigments by Multispectral Imaging: A Flowchart Method,” Heritage Science 2, no. 8 (March 17, 2014): https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7445-2-8; Joanne Dyer and Nicola Newman, “Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano-Egyptian Funerary Portraits at the British Museum,” in Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt: Emerging Research from the APPEAR Project, ed. Marie Svoboda and Caroline R. Cartwright (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2020), https://www.getty.edu/publications/mummyportraits/part-one/6/; Paolo A. M. Triolo, “Implementation of the Diagnostic Capabilities of the CMOS Sensor in the NIR Environment, Using 1070 nm Interference Filter and a Conventional IR-pass Filters Set,” in “Analytical Techniques in Art and Cultural Heritage: Selected Contributions from the TECHNART 2023 Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, May 7–12, 2023,” special issue, Journal of Cultural Heritage 70 (November–December 2024): 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.08.007. The map for iron demonstrates Smart’s use of iron oxide, from ochers and siennas, to render the hair, skin shadows, and eyes. The map also confirms his use of iron oxide pigments in the background color. The pigment composition of the hair and other features identified in this study are summarized in Table 1.

| Feature | Visible Color(s) | Inferred Partial Color Palette |

|---|---|---|

| Hair |

Pink Brown Blue White |

Iron oxide pigments Natural ultramarine* Ivory support |

| Facial features |

Shades of pink Blue White |

Iron oxide pigments Natural ultramarine Ivory support |

| Dress | White | Ivory support |

| Blue sash | Blue White |

Natural ultramarine Lead white |

| Background | Brown Pink Yellow |

Iron oxide pigments |

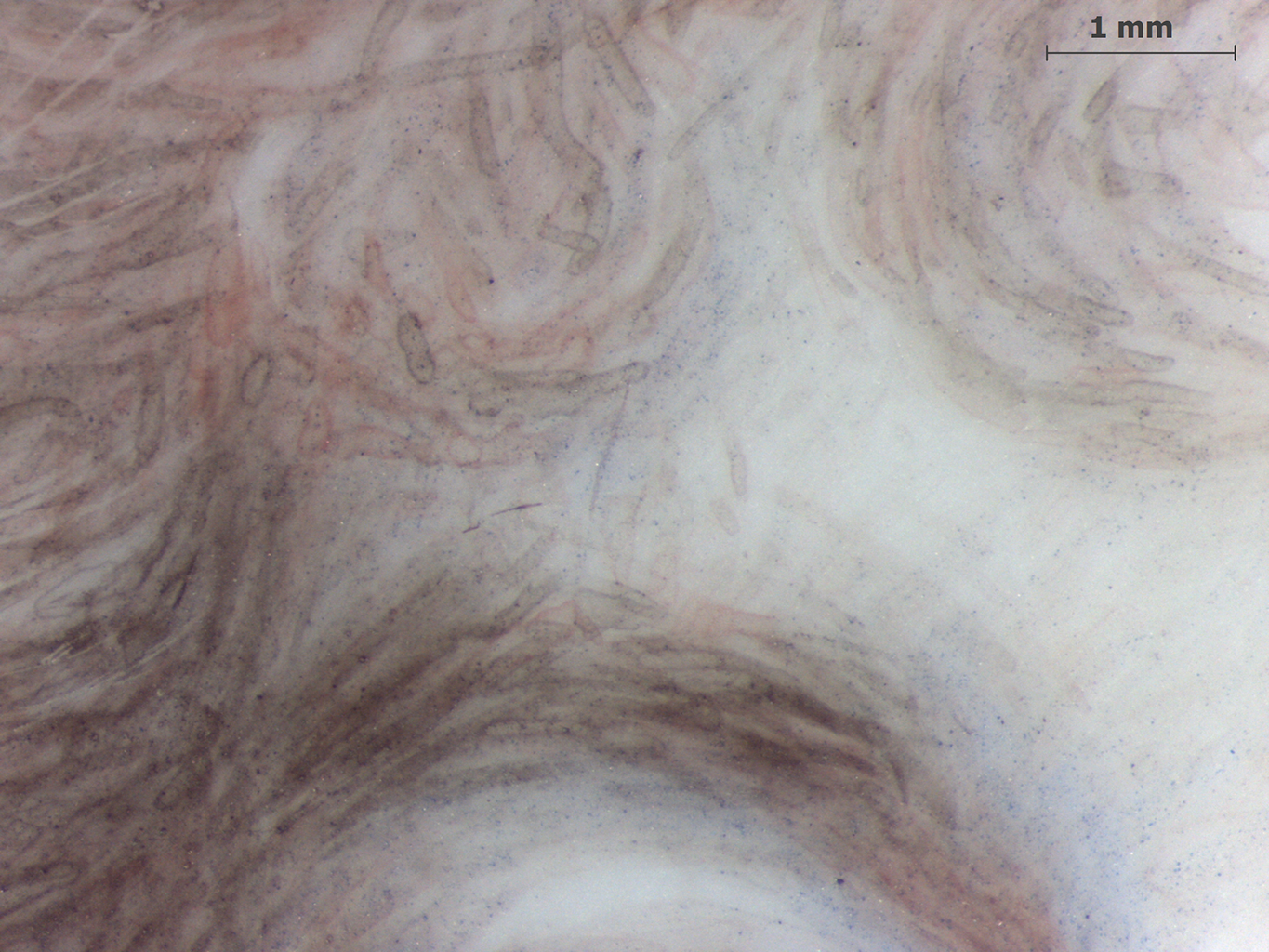

Mrs. Ronalds wears her hair in long, natural curls cascading down her back. Her light pink hair is pulled back with a headband of similar color that is partially visible on the sitter’s left side. This more relaxed, natural hairstyle, compared to the wide, frizzled: A form of tightly curled hair fashionable in the latter half of the eighteenth century. halo of Charlotte Porcher (F65-41/28), became popular at the end of the eighteenth century as powdered hair fell out of fashion. The pink tint was applied in fluid swaths of color, with a combination of broad strokes layered with finer hatching for deeper shades. Short, rounded strokes of light brown define the curls and headband, as well as shading around the neck. Under magnification, the application sequence is evident, revealing that the brown pigment was applied on top of the pink (Fig. 4). At the nape of her neck, the shadows contain dense areas of directional hatching following the curvature of the neck. Other areas of shading in the curls show how Smart laid in daubs of transparent brown paint to darken the shadows. Notably, this is the same iron oxide–based color used in the background, and Smart is relying on the pink tones and ivory to define the edge of her hair. Although used with greater restraint in this portrait than in others, Smart employed sgraffito: In Italian, meaning “scratched,” an art technique consisting of scratching through layers of paint. to reveal bare ivory for the curl highlights.

An alternative theory to the purposeful choice of pink color is the fading of some light-sensitive pigment in a mixture that would originally have given the sitter a natural hair color such as brown. Examination of pigment particles from the hair with SEM-EDS did not reveal any examples of alumina-based lakes, nor of lakes precipitated on any other compound, which would explain fading of a natural hair color to the light pink color seen today. It remains possible that an organic dye: A natural colorant made from complex organic compounds extracted from plants, animals, insects, lichens, and shellfish. As most natural colorants are soluble, they cannot be mixed directly with a binding medium and therefore must be painted directly onto the surface. Organic dyes can be further processed and precipitated onto an inorganic substrate to produce a lake pigment. See also lake pigment. with yellow, green, or brown color, in soluble form rather than as a lake pigment: An organic pigment manufactured by precipitating a soluble, natural colorant onto a colorless or white, insoluble, inorganic substrate. Historically, natural colorants were extracted from plants and insects. The substrate is traditionally hydrated aluminum oxide, but other substrates such as chalk (calcium carbonate), clay, or gypsum (calcium sulphate) have also been used., was once present along with the surviving inorganic pigments to produce a more natural hair color.6Lake pigments (suspected as a cause of fading that could result in brown hair turning pink) would be characterized by organic matter and elements such as aluminum that cannot be mapped during MA-XRF. Therefore, particular attention was paid to the detection of alumina particles or alternative lake bases in the SEM. Dye applied in dissolved form (as opposed to being supplied in the form of a dyed colorless solid or “lake”) would not be differentiated from other organic materials such as gouache medium or plant gum in these tests.

Smart deviated from his rendering of the other pink-haired sitter in this study (Portrait of a Man, F65-41/19) in his use of blue to deepen the shading in select areas of the hair. The blue wash was applied in such dilute amounts that it does not give the appearance of a lilac tint like that of the sitters in F65-41/11 and F65-41/28. The blue wash consists of pigment particles that are so thinly dispersed as to be noticeable only with the aid of magnification (Fig. 5). More blue application can be found along the forehead, where Smart added it to the curls for shading, as well as in skin for modulation of whiter flesh tones.

The map for sulfur hints at the important role played by ultramarine in this painting. Of the four elements comprising ultramarine—sodium, silicon, aluminum, and sulfur—only sulfur is mappable for such dilute paint. Moreover, because sulfur is not uniquely associated with ultramarine, other means must be employed for its confirmation. In electron microscope examination of minute samples, individual particles of crushed, natural lapis lazuli were visible. All the constituent elements of this natural form of ultramarine were confirmed to be present through x-ray spectrometry carried out with the SEM, confirming that ultramarine was used throughout the hair and background. The presence of similar blue particles in the flesh colors demonstrate that ultramarine was used in the pale skin as well, even though the concentration is too low to be mappable in MA-XRF.7The ultramarine was accompanied by colorless particles of accessory minerals that accompany the blue lazurite responsible for its color. SEM examination of microsamples confirms that the hair color involves large amounts of ultramarine and iron earths, each with their accessory minerals.

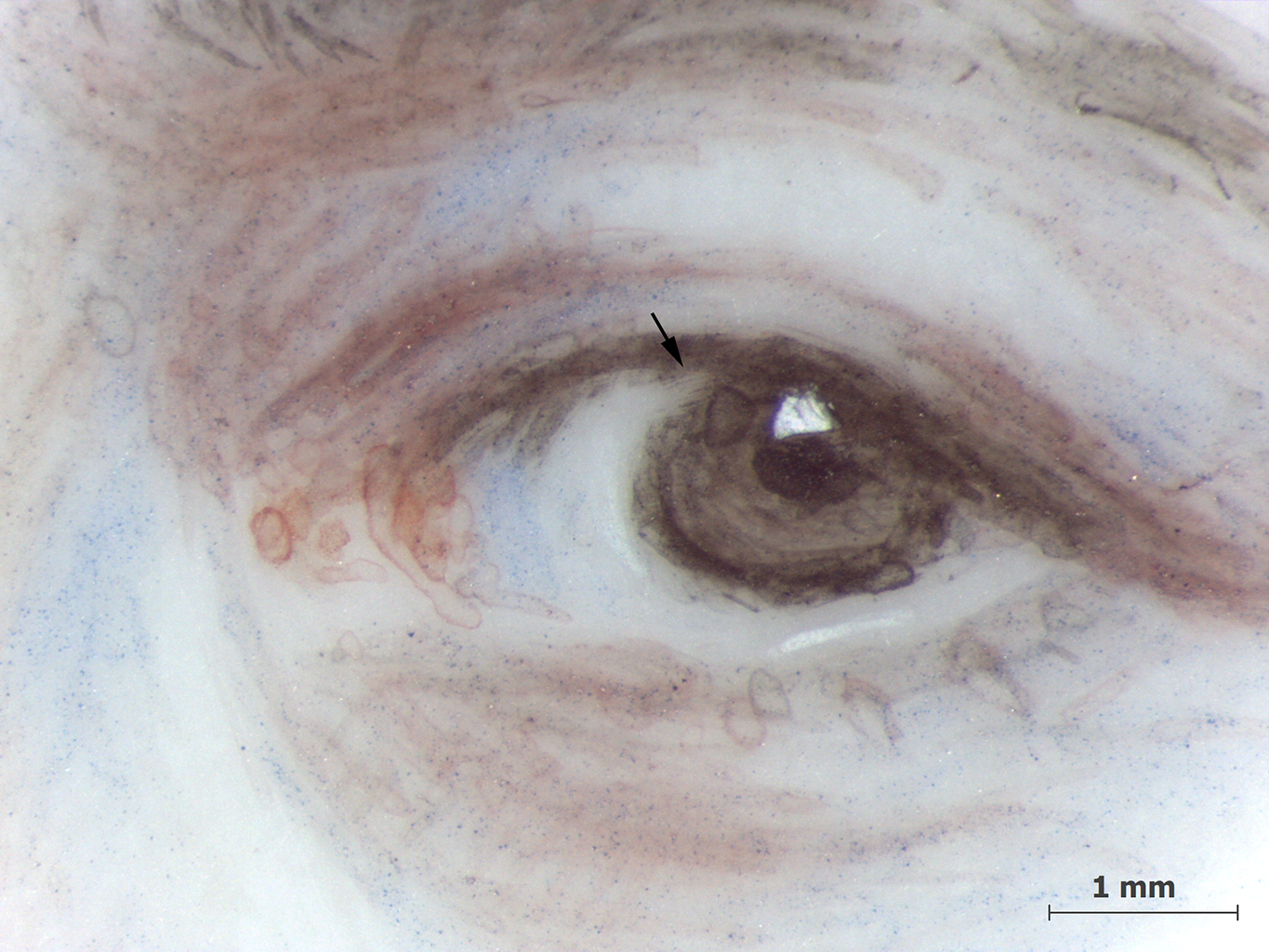

Mrs. Ronalds’ fair complexion relied heavily on the bare ivory to achieve a translucent, glowing quality, followed by delicate hatching in pale peach to add faint warmth to her skin tone. Her pale skin was further accentuated by thick, dark brows and blue shading applied in thin washes of ultramarine around her eyes, chin, and cheekbones. Peach midtones add a rosy warmth to the cheeks, nose, and chin. Her prominent cheekbones are emphasized with brown contours and blue shading applied by stippling and hatching. Smart was known for accurately capturing a sitter’s features, and here we see his depiction of the woman’s cleft chin, a beauty mark under her left eye, and a blue vein running vertically along her left temple.

The contours and shading around her brown eyes are rendered in blue, brown, and warm pink midtones. A detail of the left eye demonstrates the variety of brushstrokes in Smart’s repertoire (Fig. 6). The brown upper lash line and purple eyelid crease are painted with long, curving strokes layered to create deeper tones while the pink and purple shading around the eye and brow bone consist of shorter, directional hatching. The lower lashes and red corner of the eye are thin daubs of fluid color with visible layering of the red pigment. A wash of blue pigment around the eye was applied last. The highlights on the brow bone and under the eyes are bare ivory. The whites of the eyes are bare ivory, with white highlights painted around the iris and blue in the corners for contouring. Figure 6 also shows a revision of the composition to the left of the iris, where the artist erased the brown paint to adjust the shape, possibly with a needle-like instrument.

Although muted in this portrait, the lips are painted with two colors. The thin upper lip is a pale magenta with a high-gloss finish that appears to be a thin wash of the blue. The glossy surface is textured with air bubbles. The peach-colored lower lip was built up with short brushstrokes and daubs of paint and then left unvarnished. The highlight above the upper lip is bare ivory.

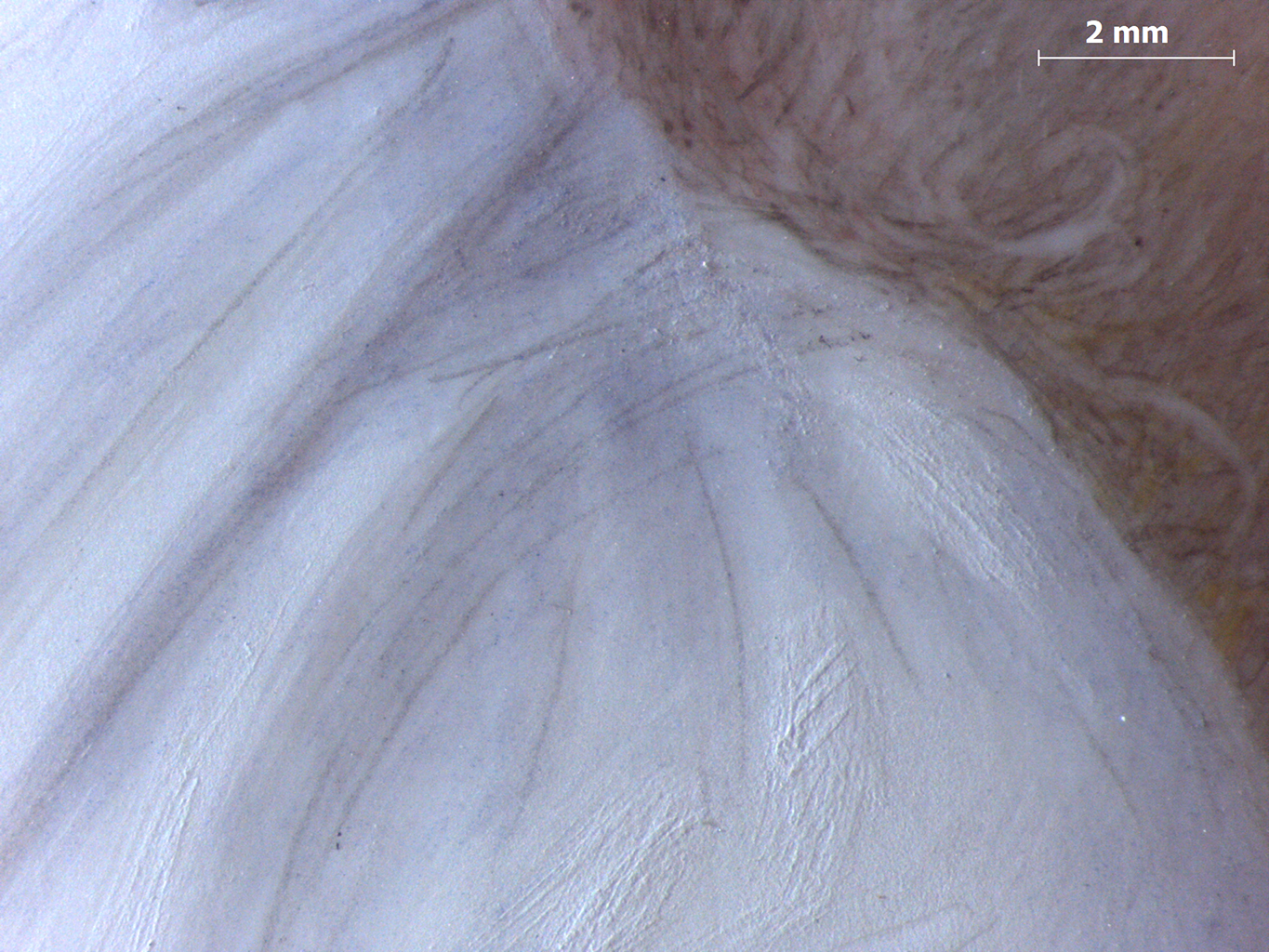

Mrs. Ronalds wears a white V-neck empire-waist dress that relies heavily upon the ivory support to achieve its lightweight, delicate appearance. The drapery in both the dress and the sash was sketched in pencil that remains exposed as an obvious inclusion in the composition. White highlights added after the initial pencil sketch are opaque and have low impasto: A thick application of paint, often creating texture such as peaks and ridges. (Fig. 7). Shading in the drapery is predominantly pencil lines and thin washes of widely dispersed blue paint (the same used in the face). This use of blue enhances the whiteness of Mrs. Ronalds’ dress and adds a crispness to the fabric not seen in the other female portrait examined for this study (F65-41/28). Light gray lines are used sparingly throughout to add to the shading.

The blue sash is tied in a bow above her waist, its wrinkles and contours also sketched in pencil. Highlights give a strong sense of the drapery in the sash. They consist of a mixture of white and blue, with emphasis provided by short, opaque white strokes applied before the overall application of blue. The application of the blue color is transparent, and the vertical folds in the dress are visible through the pigment. Directly below the sash, stray pencil lines are visible, suggesting they were part of the preparatory sketch (Fig. 8).

The blue sash is strongly depicted in the maps for sulfur and chlorine. Sulfur is elevated in the garment and facial details, where ultramarine is a component of shadows. The sulfur can be accounted for as a component of ultramarine, the most widely used blue pigment in the miniatures analyzed, but the high chlorine level in the sash is anomalous and has no clear association.

The background suggests a sunrise with warm tones of pink, yellow, brown, and gray. Short, dense hatching with overlapping colors modulates the light-to-dark gradations across the background. The directional hatching angles downward toward the left side of the object, but cross-hatching is also visible. The lighter areas of pink and yellow give luminosity to the background. Sgraffito used in multiple places blends with the paint surface and has little impact on the appearance of the background. Its most effective use is in the lighter area on the sitter’s proper left behind her hair.

The SEM revealed a few tin oxide particles in paint from the background in amounts too low to be mappable in MA-XRF. The identification of tin oxide as a white pigment in prior analyses of other miniatures suggests that it might play a role here. However, the scant occurrences here could also be attributable to the incomplete cleaning of brushes used previously on other paintings.

The miniature is mounted in a simple silver case with gold bezel. This case insert would have originally been fitted into a larger outer case, as seen with other examples of Smart’s portraits. Often the outer case would contain a decorative hair reserve or monogram; however, the original outer case for this portrait miniature no longer exists.

The results of analyses of this corpus of John Smart miniatures extend beyond the peculiarity of the sitters with light pink and lilac-tinted hair, revealing previously unknown information about Smart’s palette. Comparisons of the four portraits spanning a twenty-five-year period of Smart’s career both in London and India have brought to light ways in which he innovated beyond methods described in contemporaneous painting treatises. Additionally, they illuminate pronounced differences in his approach to representation of male and female sitters. While the analyses do not reveal lake pigments in the hair and fail to account for a color change there, the possibility remains that now-faded organic dyes, not detectable by the methods available to the authors, could account for a color change. XRF elemental mapping used in conjunction with SEM-based elemental analysis has provided pigment identifications for part of the palette. Complementary information from additional analytical steps holds the potential for a comprehensive understanding of John Smart’s palette to be derived from the extensive holdings of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

Notes

-

See Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Pretty in Pink: John Smart’s Penchant (or Not) for Pink Hair,” in this catalogue.

-

See John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1773, F65-41/11; Portrait of a Man, 1778, F65-41/19; and Portrait of Charlotte Porcher, 1787, F65-41/28.

-

The scientific study of the four John Smart portraits via x-ray spectrometry and SEM analyses was carried out by John Twilley, Mellon Science Advisor, with support of an endowment from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for conservation science at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

-

Technical imaging employs technology to observe an object in wavelength ranges that extend beyond the capabilities of the human eye, from the ultraviolet (UV) to the near infrared (NIR). Images were captured using an UV-VIS-IR-modified Nikon D7000 DSLR camera with a 60mm lens and a set of UV-VIS-IR bandpass filters. The imaging set included ultraviolet illumination (UVL), reflected infrared (IR), reflected ultraviolet (RUV), visible-induced visible luminescence (VIVL), false-color UV (FCUV), and false-color IR (FCIR). These imaging techniques can be used to make tentative identifications of artist’s materials and pigments and visualize restoration materials, such as inpainting, varnish coatings, and materials not readily visible to the naked eye. Imaging is a means to examine the surface of an artwork and discover materials that require identification through scientific analysis.

-

The yellow tone in the FCIR image for this portrait is in part due to iron-based pigments in the mixture. This behavior—an aggregate or summed-response for all the ingredients that influence the false-color appearance—exemplifies why technical imaging allows inferences to be drawn but is seldom sufficient to confirm or exclude the presence of a pigment. Antonino Cosentino, “Identification of Pigments by Multispectral Imaging: A Flowchart Method,” Heritage Science 2, no. 8 (March 17, 2014): https://doi.org/10.1186/2050-7445-2-8; Joanne Dyer and Nicola Newman, “Multispectral Imaging Techniques Applied to the Study of Romano-Egyptian Funerary Portraits at the British Museum,” in Mummy Portraits of Roman Egypt: Emerging Research from the APPEAR Project, ed. Marie Svoboda and Caroline R. Cartwright (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2020), https://www.getty.edu/publications/mummyportraits/part-one/6/; Paolo A. M. Triolo, “Implementation of the Diagnostic Capabilities of the CMOS Sensor in the NIR Environment, Using 1070 nm Interference Filter and a Conventional IR-pass Filters Set,” in “Analytical Techniques in Art and Cultural Heritage: Selected Contributions from the TECHNART 2023 Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, May 7–12, 2023,” special issue, Journal of Cultural Heritage 70 (November–December 2024): 54-63, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2024.08.007.

-

Lake pigments (suspected as a cause of fading that could result in brown hair turning pink) would be characterized by organic matter and elements such as aluminum that cannot be mapped during MA-XRF. Therefore, particular attention was paid to the detection of alumina particles or alternative lake bases in the SEM. Dye applied in dissolved form (as opposed to being supplied in the form of a dyed colorless solid or “lake”) would not be differentiated from other organic materials such as gouache medium or plant gum in these tests.

-

The ultramarine was accompanied by colorless particles of accessory minerals that accompany the blue lazurite responsible for its color.

Provenance

Unknown owner, by May 31, 1960 [1];

Purchased from the unknown owner’s sale, English and Continental Miniatures, Christie, Manson, and Woods, London, May 31, 1960, lot 80, as Mrs. Ronalds, by Leggatt Brothers, London, probably on behalf of Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, 1960–1965 [2];

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Notes

[1] According to the 1960 sales catalogue, “Different Properties” sold lots 1–80.

[2] According to the lot description, “Mrs. Ronalds, by John Smart, signed and dated 1798, three quarter face to the left, gaze directed at the artist, wearing simple white muslin dress with a narrow blue ribbon–oval, 3 1/8 in. high–unframed, in red leather case. See Frontispiece.” According to the attached price list, Leggatt bought lot 80 for £240. Archival research has shown that Leggatt Brothers served as purchasing agents for the Starrs. See correspondence between Betty Hogg and Martha Jane Starr, May 15 and June 3, 1950, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

Exhibitions

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Mrs. Ronalds.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 131, as Mrs. Ronalds.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of Mrs. Ronalds.

References

Catalogue of English and Continental Miniatures (London: Christie, Manson, and Woods, May 31, 1960), 16, (repro.), as Mrs. Ronalds.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 131, p. 46, (repro.), as Mrs. Ronalds.

No known related works at this time. If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.