Citation

Chicago:

Maggie Keenan, “John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1791,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 4, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1596.

MLA:

Keenan, Maggie. “John Smart, Portrait of a Man, 1791,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 4, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2025. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1596.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

Until recently, this portrait was believed to portray Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth (1757–1833), due to a later inscription on its reverse. However, other portraits of Pellew, including later oil paintings by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) and James Northcote (1746–1831), represent a very different character, one with rounder facial features (Fig. 1).1For reference, see Sir Thomas Lawrence, Captain Sir Edward Pellew, later 1st Viscount Exmouth, ca. 1797, oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 25 1/4 in. (76.6 x 64.2 cm), National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-201626; Owen William, Admiral Sir Edward Pellew (1757–1833), 1st Viscount Exmouth, ca. 1817–19, oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.5 cm), National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-14159. As one author remarked, “the 1797 portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence was thought a good likeness and may offer the best idea of him in his prime—a powerfully built, assured man, with a penetrating gaze and that nose.”2Stephen Taylor, Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain’s Greatest Frigate Captain (London: Faber, 2012), 76. While Pellew and the present sitter share the same light green-blue eyes, the man in miniature does not have a prominent nose; moreover, he bears a distinct scar across his chin. Later portraits of Pellew depict a scar not on his chin but on his forehead.3The Nelson-Atkins sitter is also not wearing a naval uniform, although it was not unusual for John Smart to paint military men in civilian clothing. For one example, see Portrait of John Wells, Rear-Admiral of the White (1808).

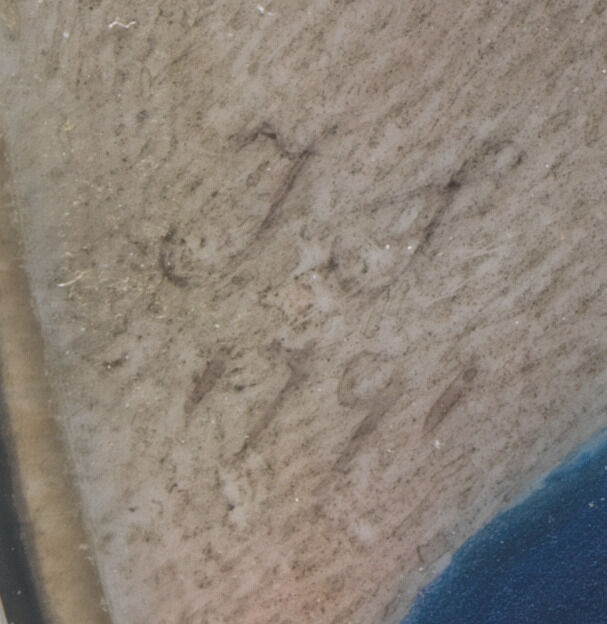

The miniature once belonged to Jeffery Whitehead (1831–1915), who owned a range of Smart miniatures, several of which included sitters with prominent military identities, so it is possible that Whitehead, or an unscrupulous dealer, added Pellew’s name to the work.4His military miniatures included portraits of Colonel Montalba (1771), Admiral Sir Charles Saunders (1778), Captain G. H. Towry (n.d.), Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis (1792), and likely others. In additional to Admiral Pellew, Whitehead owned two other Starr miniatures: Portrait of a Man (1788) and Portrait of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (1792). One more curiosity about this portrait remains: the miniature lacks Smart’s hallmark “I” inscription, which he included with miniatures made during his tenure in India (1785–1795). The date was examined more closely through high-resolution imagery, bringing up the possibility that the 1791 date may instead be 1797, which would align with Smart’s London work. However, the puddle of pigment atop the final number of the date indicates the start or stop of a brushstroke, and the tail of the first and last digit are shorter than the “7,” thus confirming it is a “1” (Fig. 2). There are very few other examples of Smart miniatures from his time in India that are not inscribed with an “I.”5Although it is difficult to tell without high-resolution imaging, there are two other possible examples: Portrait of Muhammed ‘Ali Khan, Nawab of Arcot and Prince of the Carnatic, 1789, watercolor and bodycolor on ivory, 1 x 3/4 in. (2.6 x 1.9 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, London, “Old Master and British Drawings,” July 3, 2013, lot 159, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2013/old-master-british-drawings-l13040/lot.159.html; and Portrait of a Man, 1788, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/4 x 1 5/8 in. (5.7 x 4.1 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, F65-41/29.

The miniature’s case likely originated in India, identifiable by its brightwork: A type of decorative engraving used on metal objects that is created by making a series of short cuts into the metal using a polished engraving tool that causes the exposed surfaces to reflect light and give an impression of brightness. on the back.6According to Carol Aiken, conversations with the author, May/June 2017. Notes in NAMA curatorial files. The reverse may have also held hair art: The creation of art from human hair, or “hairwork.” See also Prince of Wales feather., which has since been replaced with a fabric reserve. There are multiple explanations for what could have brought our sitter to Madras, from Honourable East India Company (HEIC): A British joint-stock company founded in 1600 to trade in the Indian Ocean region. The company accounted for half the world’s trade from the 1750s to the early 1800s, including items such as cotton, silk, opium, and spices. It later expanded to control large parts of the Indian subcontinent by exercising military and administrative power. employment, to the British army or navy, to a tradesman seeking to expand his fortune. Although this person’s erroneous name and title are now removed from the portrait’s attribution, his light teal eyes, wrinkled forehead, and scarred chin may tell a story of an adventurous life spent abroad.

Notes

-

For reference, see Sir Thomas Lawrence, Captain Sir Edward Pellew, later 1st Viscount Exmouth, ca. 1797, oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 25 1/4 in. (76.6 x 64.2 cm), National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-201626; Owen William, Admiral Sir Edward Pellew (1757–1833), 1st Viscount Exmouth, ca. 1817–19, oil on canvas, 50 x 40 in. (127 x 101.5 cm), National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-14159.

-

Stephen Taylor, Commander: The Life and Exploits of Britain’s Greatest Frigate Captain (London: Faber, 2012), 76.

-

The Nelson-Atkins sitter is also not wearing a naval uniform, although it was not unusual for John Smart to paint military men in civilian clothing. For one example, see Portrait of John Wells, Rear-Admiral of the White (1808).

-

His military miniatures included portraits of Colonel Montalba (1771), Admiral Sir Charles Saunders (1778), Captain G. H. Towry (n.d.), Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis (1792), and likely others. In additional to Admiral Pellew, Whitehead owned two other Starr miniatures: Portrait of a Man (1788) and Portrait of Lieutenant General Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (1792).

-

There are two other known examples: Portrait of Muhammed ‘Ali Khan, Nawab of Arcot and Prince of the Carnatic, 1789, watercolor and bodycolor on ivory, 1 x 3/4 in. (2.6 x 1.9 cm), sold at Sotheby’s, London, “Old Master and British Drawings,” July 3, 2013, lot 159, https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2013/old-master-british-drawings-l13040/lot.159.html; and Portrait of a Man, 1788, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/4 x 1 5/8 in. (5.7 x 4.1 cm), Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, F65-41-29.

-

According to Carol Aiken, conversations with the author, May/June 2017. Notes in NAMA curatorial files.

Provenance

Jeffery Ludlam Barton Whitehead (1831–1915), Kent, England, by January 6, 1879–at least 1903 [1];

Unknown owner, Vienna, by March 26, 1917 [2];

Unknown owner’s sale, Sammlung von Miniaturbildnissen erster Meister des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts, Albert Kende, Vienna, March 26, 1917, lot 32, as Porträt des Lord Exmouth;

Albert Leopold Lindheimer (1871–1938), Frankfurt, Germany, by May 1924 [3];

Unknown owner, London, by March 31, 1954 [4];

Purchased from the unknown owner’s sale, Objects of Art and Vertu, Miniatures, Watches, Musical Instruments, and Firearms and Weapons, Christie’s, London, March 31, 1954, lot 32, as Portrait of Admiral Lord Exmouth, by Leggatt Brothers, London, probably on behalf of Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, 1954–1965 [5];

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1965.

Notes

[1] Whitehead exhibited the miniature at the Royal Academy of Arts’ Winter Exhibition in 1879. And later, the miniature is listed in collection of Whitehead in Joshua James Foster, Miniature Painters: British and Foreign (London: Dickinsons, 1903). There was a posthumous sale of Whitehead’s miniatures in Collection of Objects of Art and Vertu Formed by Jeffery Whitehead, Esq., Christie’s, London, August 4–5, 9–11, 1915, but there is no specific reference to this portrait in the sales catalogue.

[2] The 1917 sales catalogue says, “Aus dem besitze eines bekannten wiener sammlers” (From the collection of a well-known Viennese collector).

[3] Lindheimer exhibited the miniature at Internationale Miniaturen-Austellung, Albertina, Vienna, from May to June 1924. It did not appear in his 1928 sale, Bedeutende Gemälde des 16. bis 19. Jahrhunderts; Farbstiche des 18. Jahrhunderts aus dem Besitze einer bekannten Wiener Hofburgschauspielerin; Miniaturen ersten Ranges aus den Sammlungen Albert Lindheimer, Frankfurt (Vienna: Leo Schidlof Kunstauktionshaus, March 28–29, 1928). Lindheimer was a Jewish merchant and collector, who, with his wife, founded “Adele und Albert Leopold Lindheimer-Stiftung für erholungsbedürftige Kinder aller Konfessionen” in 1918. His wife Adele Rosy Lindheimer (née Posen, b. 1875) died in London in 1965.

Another John Smart miniature previously in the Starr Collection was in the collection of Jeffery Whitehead, reproduced in Foster’s Miniature Painters (1901), and exhibited at the Albertina (1924). See John Smart, Portrait of a Boy, 1780, https://www.nelson-atkins.org/starrsupp/Other-Locations/4800/.

[4] “Different Properties” sold lots 15–118 in Objects of Art and Vertu, Miniatures, Watches, Musical Instruments, and Firearms and Weapons, Christie’s, London, March 31, 1954.

[5] Archival research has shown that Leggatt Brothers served as purchasing agents for the Starrs. See correspondence between Betty Hogg and Martha Jane Starr, May 15 and June 3, 1950, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

Exhibitions

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School, Royal Academy of Arts, Winter Exhibition, London, January 6–March 15, 1879, no. 9, p. 65, as Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth.

Exhibition of Portrait Miniatures, Burlington Fine Arts Club, London, 1889, no. 25, as Admiral Sir Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth.

Exhibition of the Royal House of Guelph, New Gallery, London, December 31, 1890–April 4, 1891, no. 975, p. 170, as Admiral Sir Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth.

Royal Naval Exhibition, Royal Hospital, Chelsea, London, May 1–October 31, 1891, no. 1891, p. 204, as Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth.

An Historical Collection of Miniatures and Enamels, Fine Art Society, London, 1892, no. 347, p. 45, as Admiral Sir Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth.

Internationale Miniaturen-Austellung in der Albertina Wien, Vienna, Albertina, May–June 1924, no. 834, p. 47, as Admiral E. H. Pallew Lord Eckmouth [sic].

John Smart—Miniaturist: 1741/2–1811, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 9, 1965–January 2, 1966, no cat., as Admiral Lord Exmouth.

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 124, as Admiral Lord Exmouth.

John Smart: Virtuoso in Miniature, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, December 21, 2024–January 4, 2026, no cat., as Portrait of a Man.

References

Exhibition of Works by the Old Masters and by Deceased Masters of the British School (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1879), 65, as Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth.

Exhibition of Portrait Miniatures (London: Burlington Fine Arts Club, 1889), no. 25, as Admiral Sir Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth.

Exhibition of the Royal House of Guelph (London: New Gallery, 1890), 170, as Admiral Sir Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth.

Royal Naval Exhibition (London: Royal Hospital, Chelsea, 1891), 204, as Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth.

Catalogue of an Historical Collection of Miniatures and Enamels (London: Fine Art Society, 1892), 45, as Admiral Sir Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth.

Joshua James Foster, Miniature Painters: British and Foreign (London: Dickinsons, 1903), no. 87, p. 113, as Exmouth, Viscount (Admiral Sir Edward Pellew).

Sammlung von Miniaturbildnissen erster Meister des 18. und 19. Jahrhunderts (Vienna: Albert Kende, March 26, 1917), no. 32.

Objects of Art and Vertu, Miniatures, Watches, Musical Instruments, and Firearms and Weapons (London: Christie’s, March 31, 1954), 8.

Daphne Foskett, John Smart: The Man and His Miniatures (London: Cory, Adams, and Mackay, 1964), 72.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 124, p. 44, (repro.), as Admiral Lord Exmouth.

Richard Walker, “Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth,” Regency Portraits Catalogue (London: National Portrait Gallery, 1985), unpaginated.

No known related works at this time. If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.