Citation

Chicago:

Maggie Keenan, “Edward Miles, Portrait of a Man, Possibly Mr. Greenlaw, ca. 1795,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 3, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1448.

MLA:

Keenan, Maggie. “Edward Miles, Portrait of a Man, Possibly Mr. Greenlaw, ca. 1795,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 3, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1448.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

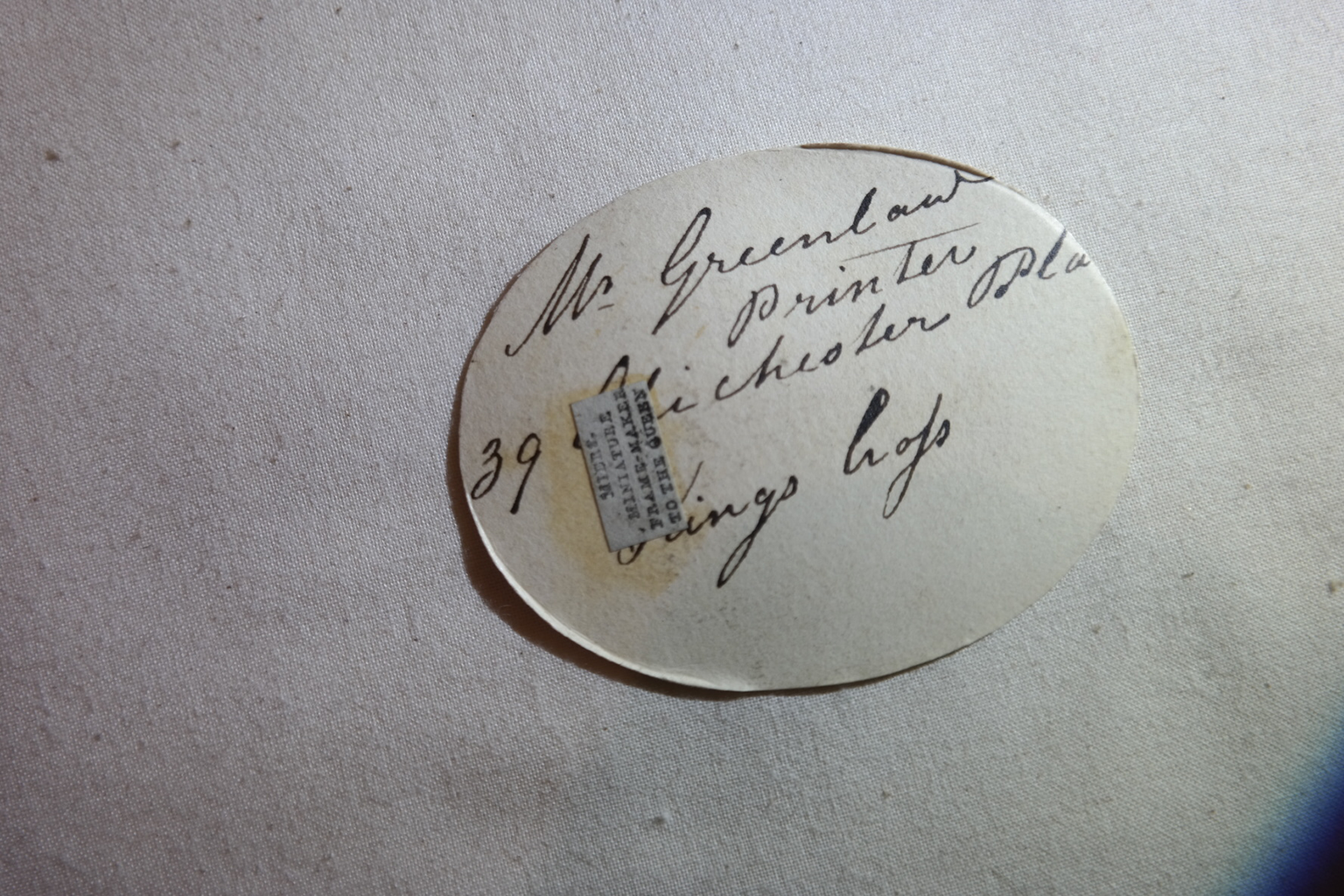

This portrait miniature was completed in London before Edward Miles left for Russia in 1797, which is reflected in the sitter’s fashion—his cravat: A cravat, the precursor to the modern necktie and bowtie, is a rectangular strip of fabric tied around the neck in a variety of ornamental arrangements. Depending on social class and budget, cravats could be made in a variety of materials, from muslin or linen to silk or imported lace. It was originally called a “Croat” after the Croatian military unit whose neck scarves first caused a stir when they visited the French court in the 1660s. and high collar date to the mid-1790s. An interior trade card discovered during the treatment of the miniature complicates a possible identification of the sitter, however. It is inscribed “Mr. Greenlaw / printer / 39 Chichester Place” (Fig. 1). The printer Robert Greenlaw (1779/80–1839)1Robert Greenlaw’s burial record gives his “abode” as Chichester Place and notes that he was buried on December 8, 1839, at the age of fifty-nine; London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P90/Pan1/186, London Metropolitan Archives. His will was probated in London, May 14, 1840: “Will of Robert Greenlaw, Printer,” May 14, 1840, PROB 11/1927/221, National Archives, Kew. In his will, Greenlaw bequeathed everything to his wife, Edith, most likely Edith Pain, whom he married on April 14, 1811, in Holborn, London; London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P69/AND2/A/01/MS 6670/10, London Metropolitan Archives, digitized on Ancestrylibrary.com. was living at 39 Chichester Place from 1829 to 1837,2See Manuel Moreno, Late Military Revolution in Buenos Ayres [sic], and Assassination of Governor Dorrego (London: R. Greenlaw, 1829), which was published from Greenlaw’s 39 Chichester Place address. Greenlaw’s other addresses were 36 High Holborn, from 1819 to 1828, and 40 Chichester Place, from 1838 to 1839; Philip A. H. Brown, London Publishers and Printers, c. 1800–1870 (London: British Library Board, 1982), 77. but he would have been too young for this ca. 1795 sitting, suggesting that the sitter is either his father or no relation at all.3I have been unable to locate Robert Greenlaw’s baptismal certificate and thereby confirm his parents. There are no other Mr. Greenlaw printers that I could trace, suggesting that he did not learn the trade from his father.

Adhered on top of the backing card is a label from William Miers (1793–1863),4William Miers was the son of the famous silhouette artist John Miers (1756–1821) (https://www.nelson-atkins.org/starrsupp/Philbrook-Museum-of-Art/1969.3.4). William Miers was working with profilist John Field (1772–1848) from 1823 to 1829; see Sue McKechnie, “Miers, William,” in British Silhouette Artists and their Work 1760–1860 (London: P. Wilson for Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978), digitized on Profiles of the Past: 250 Years of British Portrait Silhouette History, accessed April 18, 2024, http://www.profilesofthepast.org.uk/artist/miers-william. a portrait miniature frame maker. Because the cut and style of the sitter’s clothing place the miniature squarely in the last few years of the 1700s, before Miers came of age, the most logical explanation is that the Nelson-Atkins miniature was reframed between 1829 and the 1830s, when Miers called himself a “frame-maker to the queen,” as it reads on the label.5The full label reads, “MIERS, / MINIATURE / FRAME-MAKER / TO THE QUEEN.” McKechnie goes into detail examining William Miers and his use of trade cards; McKechnie, “Miers, William.” Robert Greenlaw’s card could have been inserted when Miers reframed the work, possibly as a return address for the miniature or as scrap paper to fill the case and prevent the ivory: The hard white substance originating from elephant, walrus, or narwhal tusks, often used as the support for portrait miniatures. from shifting. The handwritten identification, which lists a name, profession, and address, would seem to point to the first reason, but it remains difficult to confirm. It is possible the sitter was indeed a skilled tradesman, possibly Greenlaw or another Londoner.

Miles painted this unusually large miniature with confidence and bravado. It has one of the brightest palettes of Miles’s miniatures—or perhaps it is simply the best preserved—rivaled only by those in the Royal Collection.6For a typical, faded work, see Edward Miles, John Dawson Downes, n.d., sold at Bonhams, Knightsbridge, “Fine Portrait Miniatures,” November 23, 2011, lot 102, https://www.bonhams.com/auction/19010/lot/102. One example from the Royal Collection Trust is Edward, Duke of Kent, April–May 1791, watercolor on ivory, 2 11/16 x 2 1/8 in. (6.8 x 5.4 cm), https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/1/collection/420121/edward-duke-of-kent-1767-1820. The fluid, painterly approach to the sitter’s navy coat, using loose brushstrokes atop a wash of blue, distinguishes the garment from the detailed stippling: Producing a gradation of light and shade by drawing or painting small points, larger dots, or longer strokes. in the man’s face and hatched: A technique using closely spaced parallel lines to create a shaded effect. When lines are placed at an angle to one another, the technique is called cross-hatching. in the background. These paint application techniques, methodically employed in specific areas of the portrait, are characteristic of Miles’s style.

Notes

-

Robert Greenlaw’s burial record gives his “abode” as Chichester Place and notes that he was buried on December 8, 1839, at the age of fifty-nine; London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P90/Pan1/186, London Metropolitan Archives. His will was probated in London, May 14, 1840: “Will of Robert Greenlaw, Printer,” May 14, 1840, PROB 11/1927/221, National Archives, Kew. In his will, Greenlaw bequeathed everything to his wife, Edith, most likely Edith Pain, whom he married on April 14, 1811, in Holborn, London; London Church of England Parish Registers, ref. P69/AND2/A/01/MS 6670/10, London Metropolitan Archives, digitized on Ancestrylibrary.com.

-

See Manuel Moreno, Late Military Revolution in Buenos Ayres [sic], and Assassination of Governor Dorrego (London: R. Greenlaw, 1829), which was published from Greenlaw’s 39 Chichester Place address. Greenlaw’s other addresses were 36 High Holborn, from 1819 to 1828, and 40 Chichester Place, from 1838 to 1839; Philip A. H. Brown, London Publishers and Printers, c. 1800–1870 (London: British Library Board, 1982), 77.

-

I have been unable to locate Robert Greenlaw’s baptismal certificate and thereby confirm his parents. There are no other Mr. Greenlaw printers that I could trace, suggesting that he did not learn the trade from his father.

-

William Miers was the son of the famous silhouette artist John Miers (1756–1821). William Miers was working with profilist John Field (1772–1848) from 1823 to 1829; see Sue McKechnie, “Miers, William,” in British Silhouette Artists and their Work 1760–1860 (London: P. Wilson for Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1978), digitized on Profiles of the Past: 250 Years of British Portrait Silhouette History, accessed April 18, 2024, http://www.profilesofthepast.org.uk/artist/miers-william.

-

The full label reads, “MIERS, / MINIATURE / FRAME-MAKER / TO THE QUEEN.” McKechnie goes into detail examining William Miers and his use of trade cards; McKechnie, “Miers, William.”

-

For a typical, faded work, see Edward Miles, John Dawson Downes, n.d., sold at Bonhams, Knightsbridge, “Fine Portrait Miniatures,” November 23, 2011, lot 102, https://www.bonhams.com/auction/19010/lot/102. One example from the Royal Collection Trust is Edward, Duke of Kent, April–May 1791, watercolor on ivory, 2 11/16 x 2 1/8 in. (6.8 x 5.4 cm), https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/1/collection/420121/edward-duke-of-kent-1767-1820.

Provenance

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1958;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1958.

Exhibitions

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 161, as Unknown Man.

References

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 161, p. 55, (repro.), as Unknown Man.

No known related works at this time. If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.