Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “After Sir Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Richard Burke, ca. 1785,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 3, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1478.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “After Sir Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Richard Burke, ca. 1785,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 3, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1478.

Catalogue Entry

Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–1792) painted two portraits of the esteemed statesman and orator Richard Burke (1758–1794), son of Edmund Burke, around 1782. The portraits likely coincided with Richard Burke’s membership in the writer Samuel Johnson’s Literary Club.1See David Mannings and Martin Postle, Sir Joshua Reynolds: A Complete Catalogue of His Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), nos. 287 and 288, p. 1:115. No. 287 is the primary version of the painting, with Burke’s cravat more realized; no. 288 is the secondary version with the less finished cravat. There are at least four additional versions of the portrait of Burke noted in Mannings and Postle; see listings for catalogue numbers 288a, 288b, 288c, and 288d. There are no images of these paintings. The Club (as it was known in abbreviated form), established by Johnson and Reynolds in 1764, adds depth to the narrative surrounding Reynolds’s portraits of Burke as well as the present miniature. This gathering, initially convened to provide intellectual stimulation and conviviality for Johnson, evolved into a forum for lively debate and discourse among its members.

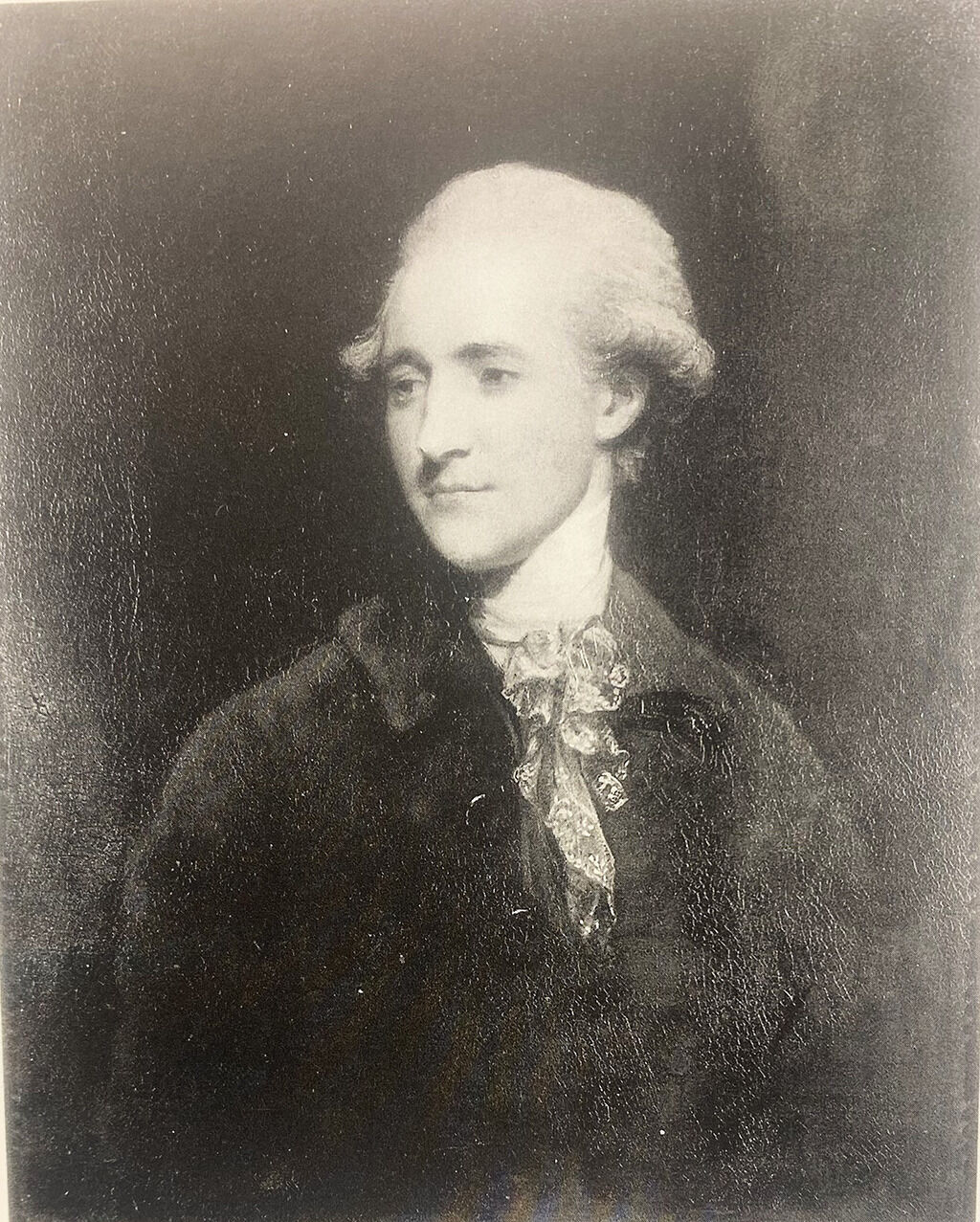

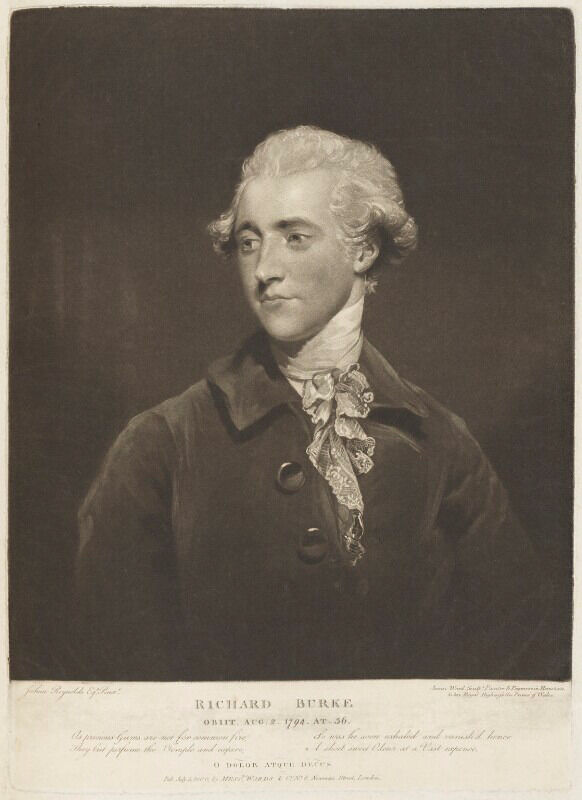

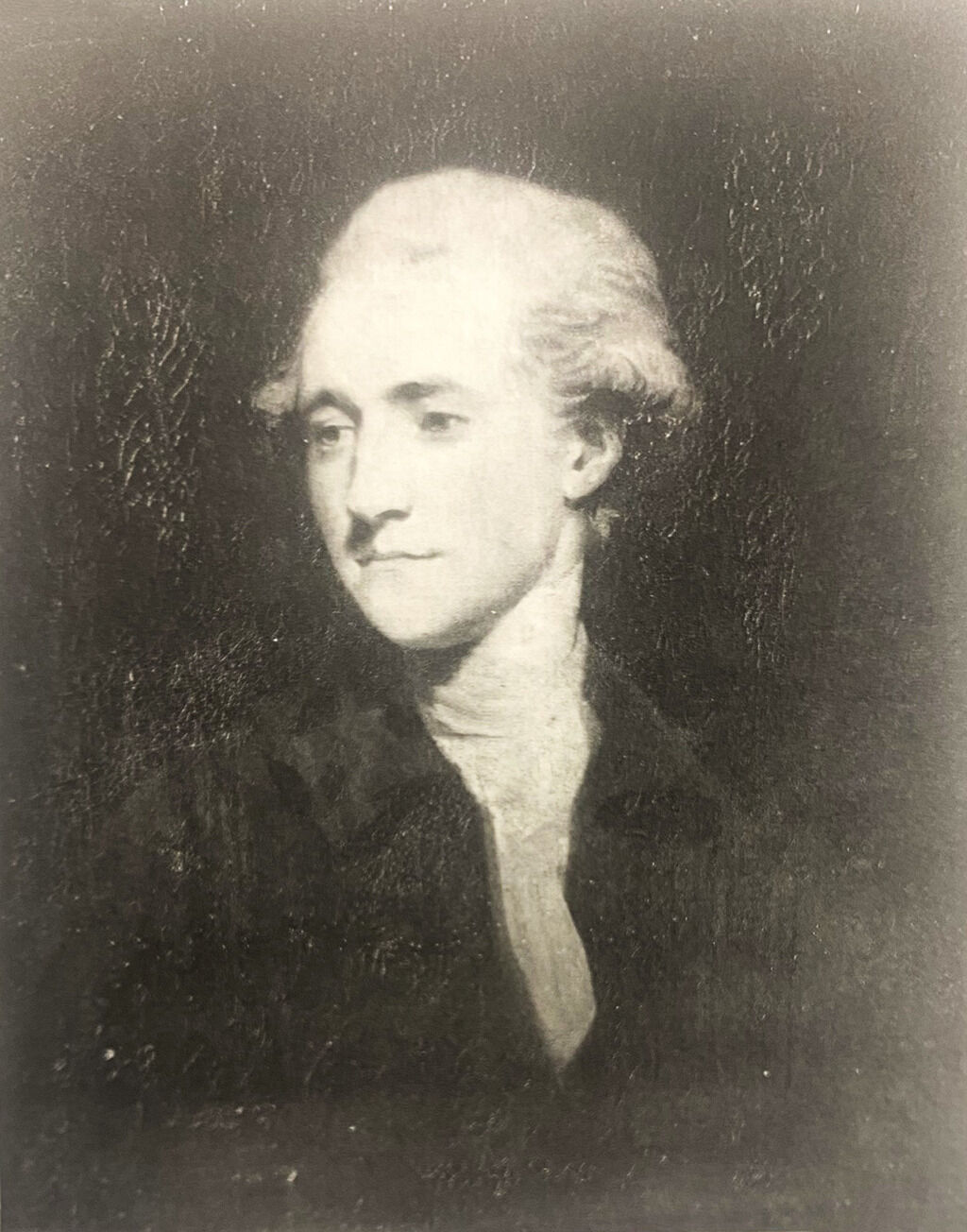

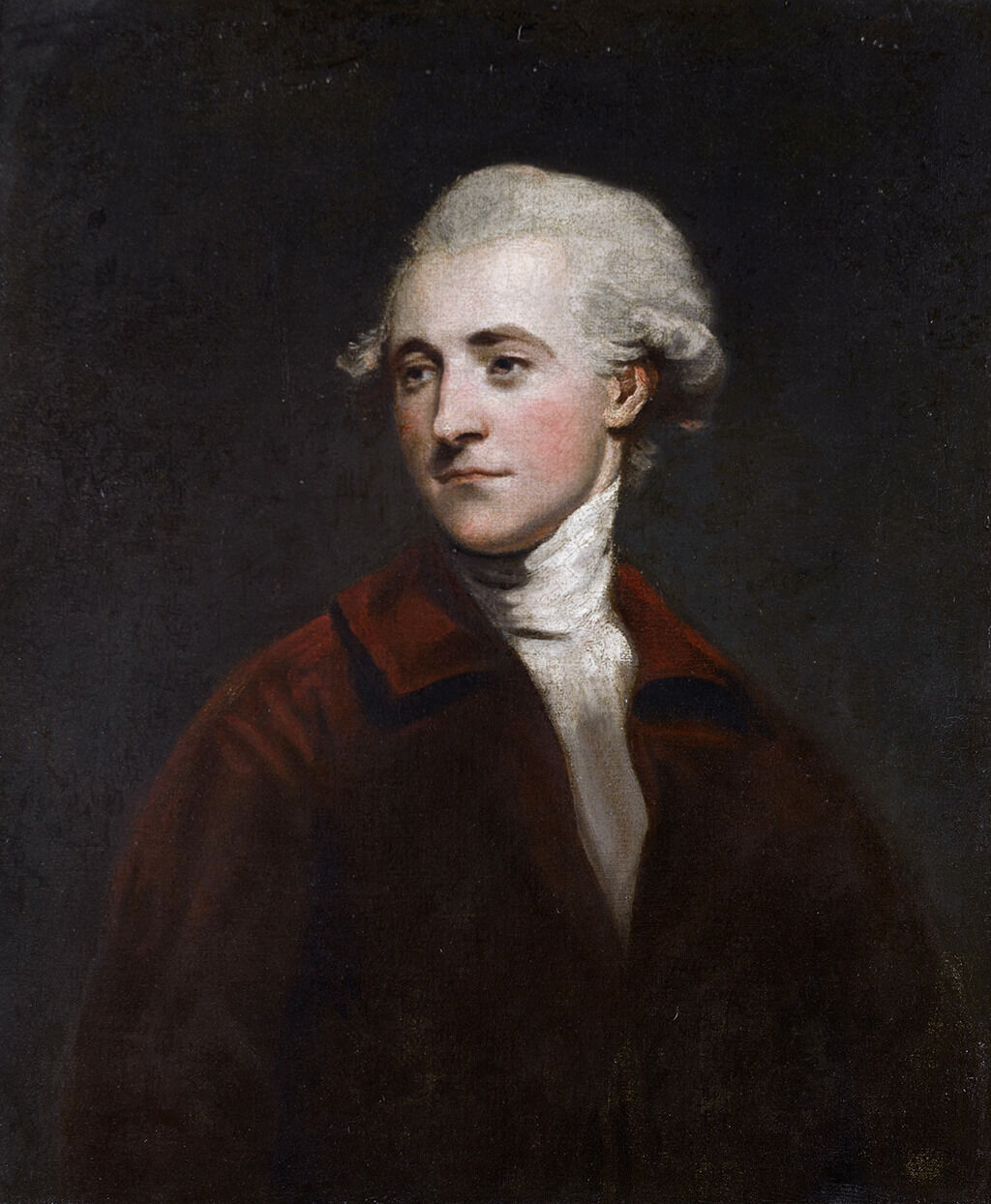

The primary version of Reynolds’s portrait of Burke is in a private collection. In it, the sitter, seen in three-quarters view, looks pensively to the left and wears a crimson red coat with double-notched collar and finely detailed white stock: A type of neckwear, often black or white, worn by men in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. tie (Fig. 1). Engraver James Ward (1769–1859) immortalized this work through an engraving (Fig. 2). Reynolds’s second version of the painting, showing Burke in a single-notched color and unfinished stock tie, is housed in the collection of the Earl of Spencer at Althorp (Fig. 3; for a closely related color image after this second version, see Fig. 4).2There are numerous copies after Reynolds’s portraits. See, for example, George Hayter (English, 1792–1871), Portrait of Richard Burke, Son of Edmund Burke, Parliamentary Agent of the Catholic Committee (1758–1794), n.d., oil on canvas, 29 1/2 x 24 in. (75 x 61 cm), National Gallery, Ireland, Dublin; and William Doughty (English, 1757–1782), after Sir Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Richard Burke, ca. 1782, oil on canvas, 24 x 20 1/8 in. (60.9 x 51.1 cm), offered for sale at Christie’s, London, “British and Victorian Paintings,” September 7, 2005, lot 47, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4565572. The present portrait miniature, likely produced shortly after Reynolds’s paintings, is a combination between the first and second versions, with Burke in a single-notched collar and unfinished stock, as seen in the second version, but with slightly more downcast eyes and a placement of the head that aligns more closely with the first. This suggests the artist of the present miniature was familiar with both versions of Reynolds’s portraits.

It is clear that, while this miniature is very accomplished, it is not by the master’s hand but by someone who understood his work.3As communicated to the author by Stephen Lloyd during his visit October 4, 2023. Notes in NAMA curatorial files. American painter Benjamin West (1738–1820) certainly would have known Reynold’s portraits, as he was in London since 1763 and found ready success there, eventually assuming Reynolds’s mantle as president of the Royal Academy of the Arts: A London-based gallery and art school founded in 1768 by a group of artists and architects. in 1792. However, the inclusion of Benjamin West’s name on the interior inscription of the miniature is evidence of the commercial priorities of the art market after the miniature was produced (likely sometime in the nineteenth century) and is in no way related to the hand associated with this miniature. Numerous artists copied works by Reynolds, whether as studio exercises or in an effort to capitalize on their marketability. These include portrait miniaturists George Engleheart (English, 1750–1829), Archibald Robertson (Scottish, 1765–1835), and William Grimaldi (English, 1751–1830). Further scrutiny of these artists’ works—Grimaldi in particular—may provide valuable insight into the context and influence of this particular example, as it may indeed prove to be by his hand.4Grimaldi copied Reynolds’s portrait of Master Bunbury, among many others. Reynolds recognized Grimaldi’s talent and recommended him to the Prince of Wales and Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany. In 1790, Grimaldi was appointed enamel painter to the Duke of York, and in 1804 he held the same appointment to the Prince of Wales. For more on Grimaldi, see Vanessa Remington, “William Grimaldi, (1751–1830),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/11633. While the artist of the present miniature remains unknown, Richard Burke’s sensitive demeanor, captured with poignant subtlety in this emulation of Reynolds’s original portrait, reflects Burke’s introspective nature as a member of Johnson’s respected social circle.

Notes

-

See David Mannings and Martin Postle, Sir Joshua Reynolds: A Complete Catalogue of His Paintings (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), nos. 287 and 288, p. 1:115. No. 287 is the primary version of the painting, with Burke’s cravat more realized; no. 288 is the secondary version with the less finished cravat. There are at least four additional versions of the portrait of Burke noted in Mannings and Postle; see listings for catalogue numbers 288a, 288b, 288c, and 288d. There are no images of these paintings.

-

There are numerous copies after Reynolds’s portraits. See, for example, George Hayter (English, 1792–1871), Portrait of Richard Burke, Son of Edmund Burke, Parliamentary Agent of the Catholic Committee (1758–1794), n.d., oil on canvas, 29 1/2 x 24 in. (75 x 61 cm), National Gallery, Ireland, Dublin; and William Doughty (English, 1757–1782), after Sir Joshua Reynolds, Portrait of Richard Burke, ca. 1782, oil on canvas, 24 x 20 1/8 in. (60.9 x 51.1 cm), offered for sale at Christie’s, London, “British and Victorian Paintings,” September 7, 2005, lot 47, https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-4565572.

-

As communicated to the author by Stephen Lloyd during his visit October 4, 2023. Notes in NAMA curatorial files.

-

Grimaldi copied Reynolds’s portrait of Master Bunbury, among many others. Reynolds recognized Grimaldi’s talent and recommended him to the Prince of Wales and Prince Frederick, Duke of York and Albany. In 1790, Grimaldi was appointed enamel painter to the Duke of York, and in 1804 he held the same appointment to the Prince of Wales. For more on Grimaldi, see Vanessa Remington, “William Grimaldi, (1751–1830),” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, September 23, 2004, https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/11633.

Provenance

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1958;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1958.

Exhibitions

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 203, as Unknown Man.

References

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 203, p. 68, (repro.), as Unknown Man.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.