Citation

Chicago:

Blythe Sobol with Cara Nordengren, “William Essex, Portrait of George Gordon, Lord Byron, 1859,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 2, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1402.

MLA:

Sobol, Blythe, with Cara Nordengren. “William Essex, Portrait of George Gordon, Lord Byron, 1859,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 2, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1402.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

This tiny miniature by the enamellist William Essex depicts an outsized personality who is widely considered the first modern celebrity: the British Romantic poet George Gordon, Lord Byron (1788–1824).1Byron’s image and his role in the creation of modern celebrity was the focus of a 2002–2003 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London: Mad, Bad and Dangerous: The Cult of Lord Byron. After the first installment of his epic poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage began selling out of bookstores in 1812, Lord Byron became an overnight sensation. His dark, brooding looks, romantic entanglements, and resemblance to his fictional character, Childe Harold, were cunningly exploited by his publishers and the author himself, who were all keenly aware of the power of his self-presentation.

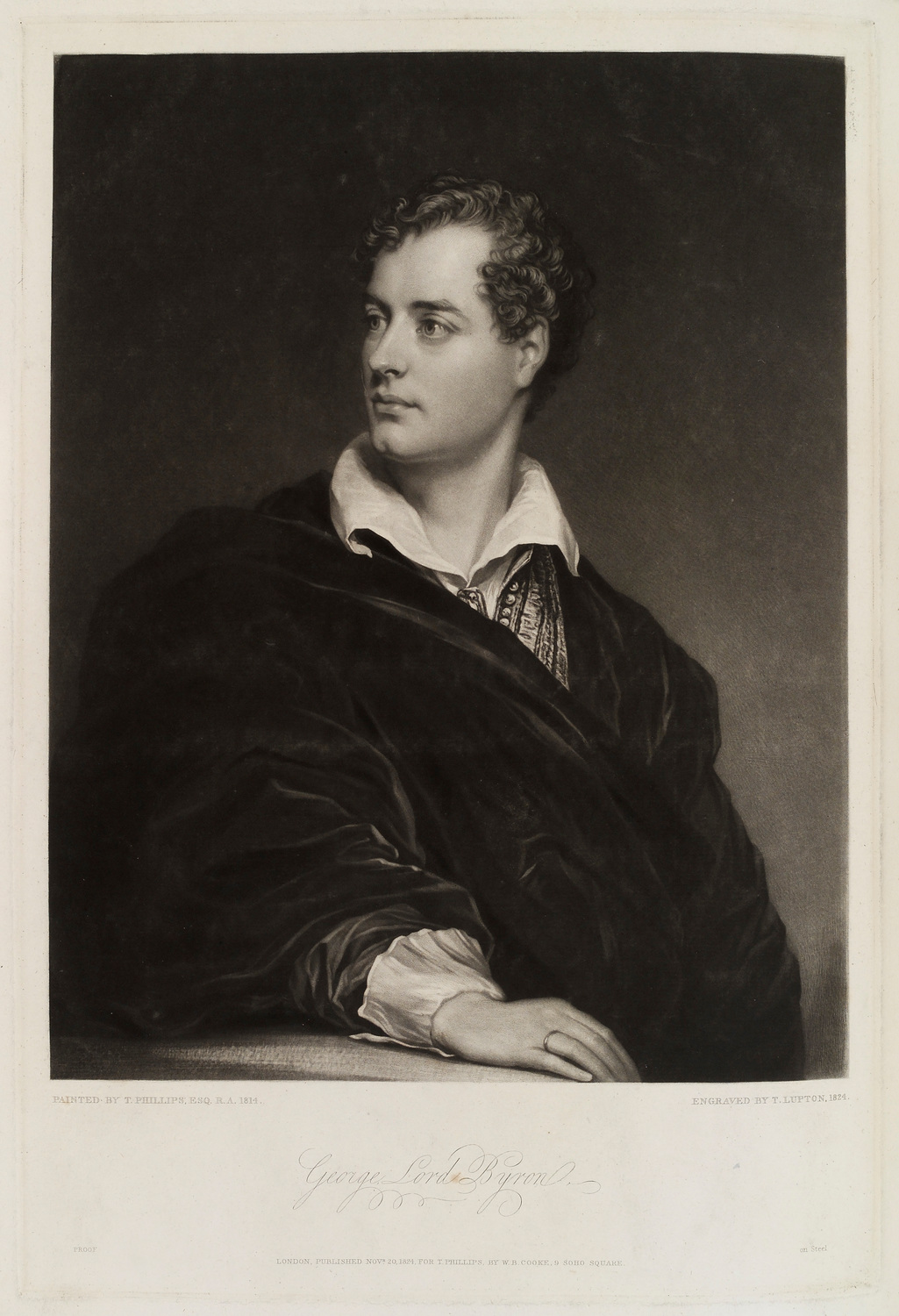

A great many portraits of Lord Byron circulated during his lifetime and, increasingly, after his premature death in 1824. These images promoted and cemented Byron’s celebrity throughout Europe. Byron encouraged the distribution of his own image, often gifting portraits of himself to friends and acquaintances. Among the most famous and widely copied of these portraits was an 1812 oil painting by Thomas Phillips (1770–1845) (Fig. 1), which Essex copied at least five times, as in this example.2Thomas Phillips’s portrait is now in the collection of Newstead Abbey, Byron’s ancestral home. While Essex occasionally painted from life, the majority of his miniatures were copies after oil paintings. He specialized in miniature portraits of celebrated writers and public figures that could be reproduced quickly and relatively inexpensively for patrons and admirers, due to their small size.3Essex also painted miniatures of William Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson, the Duke of Wellington, and Sir Walter Scott after other oil painters, including Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) and Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792). Although Essex followed his typical practice by painting this enamel on a gold support, the miniature’s small size and rapid, somewhat unpolished paint handling suggest that it was intended less as a work of art than a high-quality souvenir.4Carol Aiken, conservation treatment report, 2020, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files. Essex took the time, however, to render—in broad, undefined strokes—a red brooch pinned to Byron’s collar, perhaps the cameo of Napoleon Bonaparte, another master of self-presentation, that Byron reputedly wore.5Karl Elze, Lord Byron: A Biography with a Critical Essay on His Place in Literature (London: John Murray, 1872), 339. Byron had an abiding fascination with Napoleon. He wrote several poems inspired by the Emperor of France, including “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte” (1803), and collected coins and jewelry dedicated to him, including a cameo he gave to Lady Blessington.

Essex’s miniatures exemplify the identity that Lord Byron cultivated for himself. The louche open collar worn in this portrait became so closely entwined with his rakish, dandified persona that Byron reportedly had this sartorial detail overpainted onto earlier paintings in which he wore a closely twined cravat: A cravat, the precursor to the modern necktie and bowtie, is a rectangular strip of fabric tied around the neck in a variety of ornamental arrangements. Depending on social class and budget, cravats could be made in a variety of materials, from muslin or linen to silk or imported lace. It was originally called a “Croat” after the Croatian military unit whose neck scarves first caused a stir when they visited the French court in the 1660s..6Annette Peach, “Portraits of Byron,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 62 (2000): 37. The majority of Byron’s portraits present him with his head turned in three-quarters or full profile. This angle craftily disguises the asymmetry of his face, particularly the discrepancy in size between his eyes, which was once said to be the difference in diameter “between a shilling and a sixpence.”7Quoted in Christine Kenyon-Jones, “Byron’s Body,” in Byron: The Image of the Poet, ed. Christine Kenyon-Jones (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2008), 105. According to Kenyon-Jones, this discrepancy was noted by Byron’s contemporaries, including Lady Blessington and Augusta Leigh, as well as Byron’s classmates at Harrow College, who nicknamed him “eighteenpence.” Essex also highlights Byron’s characteristic and oft-reproduced curly hair, which he darkened with macassar oil for dramatic effect.8John Clubbe, Byron, Sully and the Power of Portraiture (New York: Routledge, 2005), 196.

All of these aspects served to create the carefully crafted look that would exemplify the “Byronic image,” which greatly influenced Romantic literature as well as men’s attire in the first half of the nineteenth century. It is fitting that Lord Byron’s miniature, one of the smallest examples in the Starr collection, was set on a stickpin, which would have secured the cravat of a man of fashion. The portrait’s late date of 1859 is a testament to the lasting adulation for Byron, the continued influence of his image, and Essex’s persistence in capitalizing on it more than half a century after the poet’s death.

Notes

-

Byron’s image and his role in the creation of modern celebrity was the focus of a 2002–2003 exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, London: Mad, Bad and Dangerous: The Cult of Lord Byron.

-

Thomas Phillips’s portrait is now in the collection of Newstead Abbey, Byron’s ancestral home.

-

Essex also painted miniatures of William Shakespeare, Samuel Johnson, the Duke of Wellington, and Sir Walter Scott after other oil painters, including Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) and Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792).

-

Carol Aiken, conservation treatment report, 2020, Nelson-Atkins curatorial files.

-

Karl Elze, Lord Byron: A Biography with a Critical Essay on His Place in Literature (London: John Murray, 1872), 339. Byron had an abiding fascination with Napoleon. He wrote several poems inspired by the Emperor of France, including “Ode to Napoleon Buonaparte” (1803), and collected coins and jewelry dedicated to him, including a cameo he gave to Lady Blessington.

-

Annette Peach, “Portraits of Byron,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 62 (2000): 37.

-

Quoted in Christine Kenyon-Jones, “Byron’s Body,” in Byron: The Image of the Poet, ed. Christine Kenyon-Jones (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2008), 105. According to Kenyon-Jones, this discrepancy was noted by Byron’s contemporaries, including Lady Blessington and Augusta Leigh, as well as Byron’s classmates at Harrow College, who nicknamed him “eighteenpence.”

-

John Clubbe, Byron, Sully and the Power of Portraiture (New York: Routledge, 2005), 196.

Provenance

Possibly George E. Butcher and Swann, Ltd., Nottinghamshire, England, before 1958 [1];

Purchased by Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1958;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1958.

Notes

[1] This miniature came enclosed in an oval-shaped red and gilt leather jewelry case fitted for a stickpin stamped with the label of George E. Butcher & Swann, Artistic Jewellers, 9 Market Street, Nottinghamshire, England. It is possible that the Essex miniature was purchased from Butcher and Swann by the Starrs or a previous owner sometime in the twentieth century, but we are unable to verify this. Butcher and Swann appears to have specialized in watches, clocks, and fine jewelry.

References

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 208, p. 70 (repro.), as Lord George Gordon Byron.

No known exhibitions at this time. If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.