Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Henry Bone, After Sir Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of King George IV as Prince Regent, 1821,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 2, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.1304.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Henry Bone, After Sir Thomas Lawrence, Portrait of King George IV as Prince Regent, 1821,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 2, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.1304.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

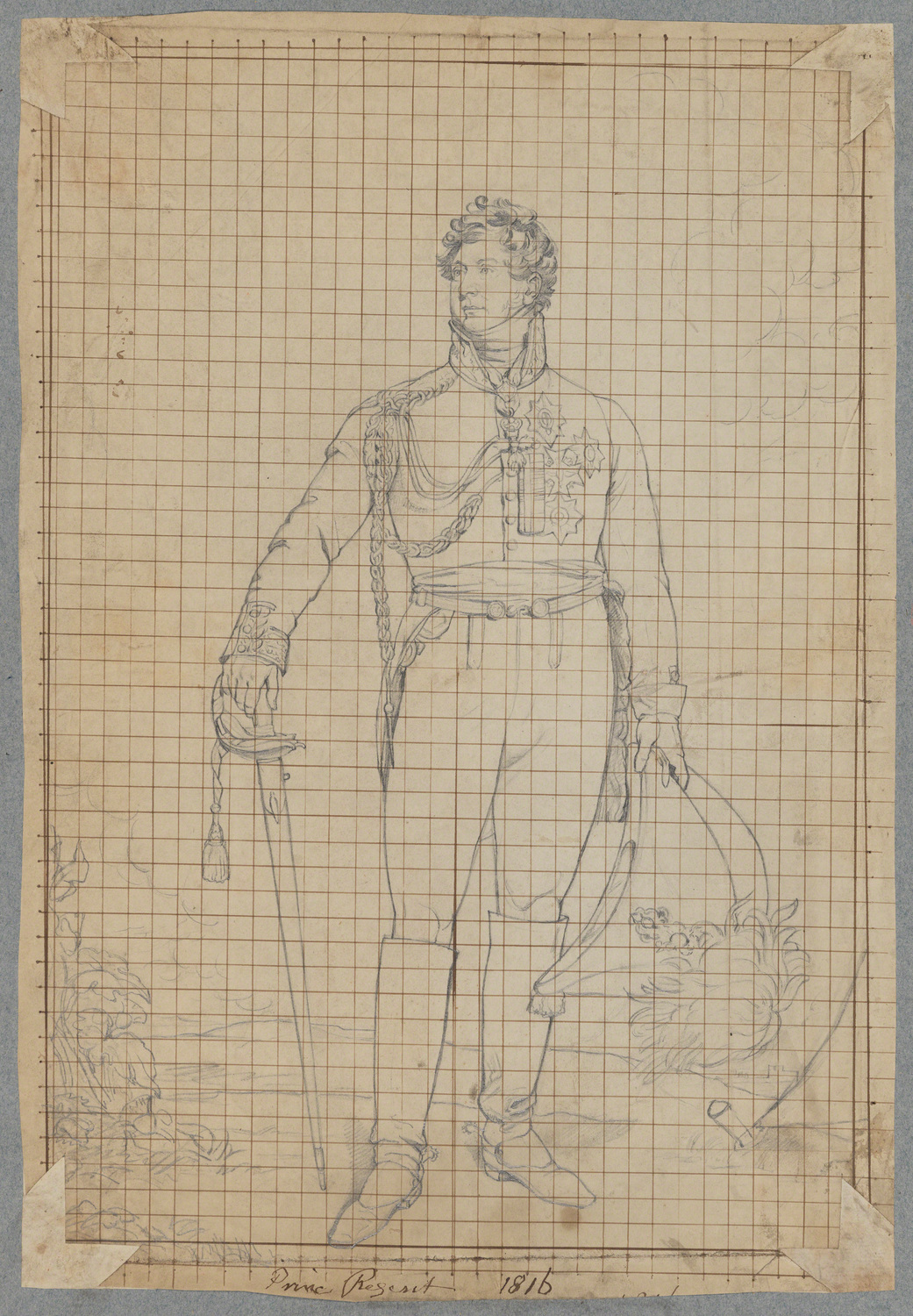

With the possible exception of Queen Victoria (1819–1901), George IV (1762–1830) sat for more artists and sculptors than any other British monarch.1Richard Walker, The Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Miniatures in the Collection of Her Majesty, the Queen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), xix. George IV sat for all the leading portrait painters of the day, often more than once, including Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–1792), Thomas Gainsborough (English, 1727–1788), George Romney (English, 1734–1802), John Hoppner (English, 1758–1810), and Sir Thomas Lawrence, among others. Portrait miniaturist Henry Bone created this bust-length portrait in enamel: Enamel miniatures originated in France before their introduction to the English court by enamellist Jean Petitot. Enamel was prized for its gloss and brilliant coloring—resembling the sheen and saturation of oil paintings—and its hardiness in contrast to the delicacy of light sensitive, water soluble miniatures painted with watercolor. Enamel miniatures were made by applying individual layers of vitreous pigment, essentially powdered glass, to a metal support, often copper but sometimes gold or silver. Each color required a separate firing in the kiln, beginning with the color that required the highest temperature; the more colors, the greater risk that the miniature would be damaged by the process. The technique was difficult to master, even by skilled practitioners, leading to its increased cost in contrast with watercolor miniatures. when George IV was Prince Regent, copying a full-length oil portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1815.2Lawrence’s portrait of George IV as Prince Regent was commissioned by Charles William Vane-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, in 1814 for the British Embassy in Vienna. It is now at Wynyard Park in the collection of the first owner’s direct descendant, the Marquess of Londonderry. See Kenneth Garlick, Sir Thomas Lawrence: A Complete Catalogue of the Oil Paintings (Oxford: Phaidon, 1989), 325c. The Lawrence portrait was exhibited as no. 65 at the Royal Academy in 1815 and was popular among miniature copyists. Many versions exist in both watercolor on ivory and enamel not only by Bone but also by Johann Paul Georg Fischer (German, 1786–1875) and others. As in the Lawrence original, the full-figured, fifty-three-year-old prince appears like a sculpted Adonis in his favorite scarlet field marshal’s uniform.3The uniform also consists of a black collar embroidered in gold with oak leaves, gold aiguillettes, and buttons. Set against a brown background, with his windswept chestnut hair in tousled abundance, he wears the insignia of the Order of the Golden Fleece and the stars of the Orders of the Garter, Holy Spirit, Black Eagle, and St. Andrew. Numerous miniature replicas after the Lawrence portrait were made soon after its exhibition and for many years thereafter, suggesting that the demand for such images was immediate—and, for the budding monarch, constant, since he liked to give them away as presents.4There are eight enamel miniatures of George IV as Prince Regent in his scarlet field marshal’s uniform within the Royal Collection alone. See Walker, Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Miniatures, nos. 757–63, 765, pp. 281–83. There are also examples of Bone enamels after the Lawrence portrait in his scarlet uniform at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

From 1811 until his formal accession in 1820, George Augustus Frederick served as Prince Regent during the mental illness of his father, King George III (1738–1820). A notorious playboy of his time, whose numerous dalliances accounted for several illegitimate children and mounting financial debt, the Prince Regent had many harsh critics, including the Duke of Wellington, who declared him “entirely without one redeeming quality.”5As cited in Christopher Hibbert, George IV, Regent and King, 1811–1830 (London: Allen Lane, 1973), 310. Although not remembered as a great leader, George IV distinguished himself sartorially. Following the tax on hair powder in 1795, he wore his hair unpowdered, helping to foment a return to naturalism. He wore darker colors to minimize his size, favored trousers over knee breeches because they accommodated his girth, and preferred a high collar with neck cloth to hide his double chin.6Steven Parissien, George IV: The Grand Entertainment (London: John Murray, 2001), 114. These fashion choices, many of which can be seen in the Bone portrait, became hallmarks of Regency: Part of the Georgian era, when King George III’s son ruled as his proxy, dating from approximately 1811 until 1820. dress (ca. 1811–1820), so named because it aligned with the period prior to the Prince Regent’s ascension to the throne.

Notes

-

Richard Walker, The Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Miniatures in the Collection of Her Majesty, the Queen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), xix. George IV sat for all the leading portrait painters of the day, often more than once, including Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–1792), Thomas Gainsborough (English, 1727–1788), George Romney (English, 1734–1802), John Hoppner (English, 1758–1810), and Sir Thomas Lawrence, among others.

-

Lawrence’s portrait of George IV as Prince Regent was commissioned by Charles William Vane-Stuart, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, in 1814 for the British Embassy in Vienna. It is now at Wynyard Park in the collection of the first owner’s direct descendant, the Marquess of Londonderry. See Kenneth Garlick, Sir Thomas Lawrence: A Complete Catalogue of the Oil Paintings (Oxford: Phaidon, 1989), 325c. The Lawrence portrait was exhibited as no. 65 at the Royal Academy in 1815 and was popular among miniature copyists. Many versions exist in both watercolor on ivory and enamel, not only by Bone but also by Johann Paul Georg Fischer (German, 1786–1875) and others.

-

The uniform also consists of a black collar embroidered in gold with oak leaves, gold aiguillette: Braided loops that hang from the shoulder of a military uniform., and buttons.

-

There are eight enamel miniatures of George IV as Prince Regent in his scarlet field marshal’s uniform within the Royal Collection alone. See Walker, Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Miniatures, nos. 757–763, 765, pp. 281–83. There are also examples of Bone enamels after the Lawrence portrait in his scarlet uniform at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

-

As cited in Christopher Hibbert, George IV, Regent and King, 1811–1830 (London: Allen Lane, 1973), 310.

-

Steven Parissien, George IV: The Grand Entertainment (London: John Murray, 2001), 114.

-

Bone’s association with the royal family began in 1797, when the Prince of Wales commissioned an enamel of Princess Mary, Duchess of Gloucester (Royal Collection Trust, RCIN 421505). It continued with Bone’s appointment as enamel painter to the Prince of Wales in 1801, and thereafter to George III, George IV, and William IV. See Walker, Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Miniatures, no. 769, pp. 285–86. George IV had been a connoisseur and collector since he was the Prince of Wales, under the chief advisement of his then–principal painter and miniaturist, Richard Cosway (English, 1742–1821).

-

This was the second such drawing Bone did; one dated November 1815 appeared in the Princess Royal’s sale, Christie’s, June 28, 1966, lot 242, as cited in Walker, Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Miniatures, 281. Bone stored these drawings for future use. They were eventually assembled; annotated by Bone or one of his sons, William or Henry Pierce Bone; and pasted into three large albums that are housed today at the National Portrait Gallery in London. For more on Bone’s pencil drawings, see Richard Walker, “Henry Bone’s Pencil Drawings in the National Portrait Gallery,” The Volume of the Walpole Society 61 (1999): 306.

-

A note found in Bone’s itemized accounts for July 20, 1816, for a similar miniature provides a clue as to Bone’s prices: “H.R.H. the Prince Regent—Oval 2 5/8 x 2 1/2 on Gold—all the Orders—New Picture 45 guineas.” See Walker, Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century Miniatures, 281.

-

Queen Victoria’s memoir, written in 1872; quoted in Arthur Christopher Benson and Reginald Baliol Brett Esher, The Letters of Queen Victoria: A Selection from Her Majesty’s Correspondence between the Years of 1837 and 1861 (London: J. Murray, 1908), 1:16.

Provenance

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1958;

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1958.

Exhibitions

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 167, as His Majesty, George IV.

References

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 167, p. 57, (repro.), as His Majesty, George IV.

Richard Walker, “Henry Bone’s Pencil Drawings in the National Portrait Gallery,” Volume of the Walpole Society 61, no. 218 (1999): 327.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.