Citation

Chicago:

Blythe Sobol, “Jean-Baptiste Isabey, Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1825,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 1, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.2308.

MLA:

Sobol, Blythe. “Jean-Baptiste Isabey, Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1825,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 1, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.2308.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

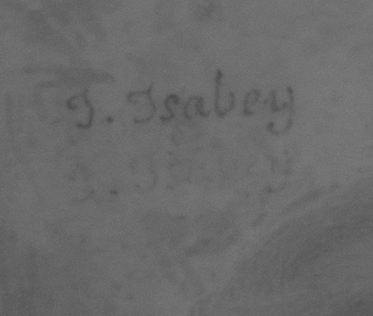

Grandly surrounded by a neoclassical gilt frame bordered with palmette: A motif originating in ancient Egyptian designs that resembles the fan-shaped leaves of a palm tree. and egg-and-dart: A motif used in neoclassical architecture and decorative arts, particularly molding and framing, that alternates an ovoid shape with a v-shaped element resembling a dart, arrow, or anchor. motifs, this pink-and-white confection of an unknown lady epitomizes Jean-Baptiste Isabey’s watercolor: A sheer water-soluble paint prized for its luminosity, applied in a wash to light-colored surfaces such as vellum, ivory, or paper. Pigments are usually mixed with water and a binder such as gum arabic to prepare the watercolor for use. See also gum arabic. portraits painted after 1800. Established in his career and no longer needing to display his powers of invention in each new commission, Isabey used a standard formula, with the sitter placed against a light background on a large oval support, typically paper or sometimes vellum: A fine parchment made of calfskin. A thin sheet of vellum was typically mounted with paste on a playing card or similar card support. See also table-book leaf..1According to miniatures conservator Carol Aiken, Isabey often mounted these larger miniatures on plated iron ovals, and the paper or vellum was wrapped around it and glued. In many cases, as with this portrait, the iron eventually began to rust, causing brown staining on the surface of the miniature. Much of this staining was lifted in a treatment by Nelson-Atkins conservator Rachel Freeman in 2022. NAMA curatorial files, 2018 and 2022. While we do not know the identity of the woman depicted in this miniature, she was probably an aristocrat or a wealthy woman angling to join their ranks, as were most of his sitters. Isabey rendered his typically high-born, well-connected female subjects in a gauzy, romantic style, often with filmy draperies swirling around them to frame their features to their best effect (Fig. 1).2Many such examples are illustrated in Basily Callimaki, J. B. Isabey: Sa Vie—Son Temps (Paris: Frazier-Soye, 1909). Formulaic as these depictions may seem, they are full of Isabey’s trademark charm and romanticism. His sleight of hand is evident here in his proto-pointillist technique, using tiny dots of pigment to create a soft, diffuse radiance, particularly in the flesh tones. Isabey’s perfectionism is evident in a pentimento: From the Italian for “repentance,” a pentimento or pentiment, plural pentimenti, is an area revealing an element of the composition that has been moved or removed from the final composition. This is typically seen in underdrawing or elements hidden beneath added layers of paint, called overpaint. Pentimenti can be revealed by thinning layers of paint over time, or through the course of technical analysis with methods like x-radiographs or infrared reflectography. revealed through infrared (IR) photography: A form of infrared imaging that employs the part of the spectrum just beyond the red color to which the human eye is sensitive. This wavelength region, typically between 700–1,000 nanometers, is accessible to commonly available digital cameras if they are modified by removal of an IR-blocking filter that is required to render images as the eye sees them. The camera is made selective for the infrared by then blocking the visible light. The resulting image is called a reflected infrared digital photograph. Its value as a painting examination tool derives from the tendency for paint to be more transparent at these longer wavelengths, thereby non-invasively revealing pentimenti, inscriptions, underdrawing lines, and early stages in the execution of a work. The technique has been used extensively for more than a half-century and was formerly accomplished with infrared film. (Fig. 2), which shows that he originally signed his name, “J. Isabey,” below the visible signature, closer to the sitter’s shoulder.3The reflected infrared digital photograph was produced on June 21, 2022, with a Nikon D700 UV-VIS-IR modified camera with Kodak Wratten 87C filter. Perhaps deciding that the proximity was too tight, Isabey covered his name with paint and re-signed it above.

The sitter’s tight curls and high-waisted gown with puffy leg-of-mutton: A prominent sleeve style, also called a gigot sleeve, mouton sleeve, or mutton sleeve, that was popular during the 1500s, 1830s, 1840s, and 1890s, which resembles the sharply tapered shape of a mutton (mature sheep) leg. It is characterized by a large amount of fullness in the shoulder, which narrows to a closely fitted sleeve at the wrist. sleeves date this portrait to about 1825. Frothy, pleated rows of sheer white material around her neck approximate an Elizabethan ruff, a fashion that had reemerged with the style troubadour: A style of French historical painting, fashion, and decorative art that evoked a nostalgic, romanticized medieval past in an age of revolutionary upheaval. popularized by the Empress Josephine and her daughter, Hortense de Beauharnais, in the earlier part of the century.4Cyril Lécosse has noted that Isabey produced a number of works between 1821 and 1827 under the influence of the style troubadour. Cyril Lécosse, Jean-Baptiste Isabey: Petits Portraits et Grands Desseins (Paris: CTHS Edition, 2018), 264–66. The sitter’s lace cap skims her cheeks and dips over her forehead like a widow’s peak in layers of scalloped, buoyant lace, secured beneath her chin with a plump pink satin bow.5A similar cap appears in a miniature in the Wallace Collection: Manner of André Léon Larue, An Unknown Lady, 1820–70, watercolor on ivory, 5 1/2 x 4 1/8 in. (14.1 x 10.5 cm), Wallace Collection, London, M278, https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org:443/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=64466&viewType=detailView. Such caps were worn by all but the youngest of women not only for comfortable—if respectable—undress at the breakfast table but also out in public. The lush pink roses adorning the cap and corsage suggest that the sitter was dressed more formally, as floral embellishments in France were typically worn outside the home at this time.6“Breakfast caps are either trimmed with knots or cockades of riband, or close wreaths made of riband, or rosettes composed of a mixture of riband and lace; flowers are never worn in complete dishabille; and I am sure, in this respect, all my fair readers will agree with me, that French taste is correct.” “The Mirror of Fashion for August, 1820: Cabinet des Modes de Paris,” The Ladies’ Monthly Museum 12 (July 1820): 111. The feminine grace of Isabey’s miniatures made them particularly desirable in the nineteenth- and twentieth-century art markets, and the appeal of Isabey’s refined draftsmanship is everlasting.

Notes

-

According to miniatures conservator Carol Aiken, Isabey often mounted these larger miniatures on plated iron ovals, and the paper or vellum was wrapped around it and glued. In many cases, as with this portrait, the iron eventually began to rust, causing brown staining on the surface of the miniature. Much of this staining was lifted in a treatment by Nelson-Atkins conservator Rachel Freeman in 2022. NAMA curatorial files, 2018 and 2022.

-

Many such examples are illustrated in Basily Callimaki, J. B. Isabey: Sa Vie—Son Temps (Paris: Frazier-Soye, 1909).

-

The reflected infrared digital photograph was taken by Rachel Freeman on June 21, 2022, with a Nikon D700 UV-VIS-IR modified camera with Kodak Wratten 87C filter.

-

Cyril Lécosse has noted that Isabey produced a number of works between 1821 and 1827 under the influence of the style troubadour. Cyril Lécosse, Jean-Baptiste Isabey: Petits Portraits et Grands Desseins (Paris: CTHS Edition, 2018), 264–66.

-

A similar cap appears in a miniature in the Wallace Collection: Manner of André Léon Larue, An Unknown Lady, 1820–70, watercolor on ivory, 5 1/2 x 4 1/8 in. (14.1 x 10.5 cm), Wallace Collection, London, M278, https://wallacelive.wallacecollection.org:443/eMP/eMuseumPlus?service=ExternalInterface&module=collection&objectId=64466&viewType=detailView.

-

“Breakfast caps are either trimmed with knots or cockades of riband, or close wreaths made of riband, or rosettes composed of a mixture of riband and lace; flowers are never worn in complete dishabille; and I am sure, in this respect, all my fair readers will agree with me, that French taste is correct.” “The Mirror of Fashion for August, 1820: Cabinet des Modes de Paris,” The Ladies’ Monthly Museum 12 (July 1820): 111.

Provenance

Amélie Levaigneur (née Grondard, 1824–1912), Paris, by 1912 [1];

Sold at her posthumous sale, Tableaux Anciens, Oeuvre Importante de Rembrandt Et Autres par J. Both, Thomas de Keyser, Jacob Ruysdael, Ph. Wouwerman, etc.; Tableaux Modernes par Diaz, Troyon, etc. . . . Dont La Vente Par suite du Décès de Madame Levaigneur, Hôtel Drouot, Paris, May 4, 1912, lot 242, as Portrait de femme [2];

Madame Dhainaut, Paris, by 1936 [3];

Purchased from her sale, Very Choice Collection of Works of Art, the Property of Madame Dhainaut of Paris, Sotheby and Co., London, December 10, 1936, lot 12, as An Attractive Miniature of a Lady, by Frost and Reed, London, probably on behalf of George Herbert Kemp (1886–1940), The Darlands, Totteridge, Hertfordshire, 1936–1940 [4];

Purchased at Kemp’s posthumous sale, Old English Silver, Fine Portrait Miniatures and Objects of Vertu, Sotheby’s, London, July 31, 1952, lot 114, as Lady by Leggatt Brothers, London, probably on behalf of Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, 1952–1958 [5];

Their gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1958.

Notes

[1] With thanks to Bailey McCulloch for her assiduous research and discovery of the Levaigneur and Dhainaut provenance, and to Meghan Gray for further sleuthing. According to Levaigneur’s sales catalogue, she inherited the collection of her godfather, Théodore Dablin (1783–1861), to which she added her own purchases. For Dablin’s biography, see Antoine Maës, “L’illustre ascendance de Théodore Dablin: ‘Une famille de serruriers du roi’ à Rambouillet sous Louis XVI,” L’Année balzacienne 18, no. 1 (2017): 41–66.

[2] The miniature is illustrated as lot 242 of the Levaigneur sale and described as “Grande miniature ovale: Portrait de femme, en buste, vétue de blanc, portant une ceinture rose, coiffée d’un bonnet tuyauté orné de deux roses, par J. Isabey. Signée.”

[3] Madame Dhainaut remains unidentified, but her husband was the director of the casinos in Spa (from about 1889 until at least 1900) and Enghien-les-Bains (1906–1912), a chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur (1912), and he contributed money to the casino in Touquet-Paris-Plage. See Georges Bal, “La Curiosité,” New York Herald (May 18, 1924): 5. She was a widow by 1926 and living in Touquet-Paris-Plage. See “Deuil,” Journal de Montreuil et de l’arrondissement (August 22, 1926): 2. We have been unable to identify them further. However, she had a significant collection of decorative arts and portrait miniatures that are now spread across major private collections and museums, including the Wallace Collection, the British Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Walters Art Gallery, and the Nelson-Atkins. A Sèvres urn in the Nelson-Atkins collection also previously belonged to Madame Dhainaut (33-1580/2), https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/18208/urn.

[4] Ten miniatures belonging to “the late Herbert Kemp, Esq.” were sold at Sotheby’s in 1952, including this portrait, with the proceeds “sold on behalf of the Musicians’ Benevolent Fund,” which may be an avenue for future research on Mr. Kemp.

Notably, a miniature today in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, P.12-1940, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O81921/an-unknown-man-possibly-james-portrait-miniature-gibson-richard/, has a similar provenance. In 1935 (the year before the Dhainaut sale), Frost and Reed, a longstanding London art dealer, purchased that miniature on behalf of a Mr. G. H. Kemp from Christie’s, June 24, 1935, lot 51 (known at the time as by Lawrence Crosse, Portrait of Sir Robert Walpole). When G. H. Kemp died in 1940, his executors sold the miniature, again through Frost and Reed, to the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. See John Murdoch, Seventeenth-Century English Miniatures (London: Stationery Office, 1997), 194. G. H. Kemp is also listed as the owner in 1938 of a miniature self-portrait by John Smart, now also in the V&A collection, P.11-1940, https://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O75215/miniature-self-portrait-of-john-portrait-miniature-smart-john/. See Ralph Edwards, “English Miniatures at the Louvre,” Burlington Magazine 72, no. 422 (May, 1938): 225.

Both “G. H. Kemp” and “Herbert Kemp, Esq.,” whose executors sold the Nelson-Atkins miniature in 1952, are most likely George Herbert Kemp, a biscuit magnate, who died on January 16, 1940. While a twelve-year gap between his death in 1940 and the 1952 sale is substantial, Kemp’s widow Margaret Prudence Kemp lived until 1959, and it is not improbable that Kemp’s executors assisted her with the sale of the miniatures later in her life. It may be of interest that a miniature of a “Mrs. Herbert Kemp” by Miss Edith Kemp-Welch was displayed in the forty-third annual exhibition of the Royal Society of Miniature Painters, Sculptors and Gravers at the Arlington Gallery, 22, Old Bond Street, in 1938, but the name was so common that they may not be related.

[5] Archival research indicates that the Starrs purchased many miniatures from Leggatt Brothers, either directly or with Leggatt acting as their purchasing agent.

Exhibitions

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 242, as Unknown Lady.

References

Catalogue de Tableaux Anciens, Oeuvre Importante de Rembrandt Et Autres par J. Both, Thomas de Keyser, Jacob Ruysdael, Ph. Wouwerman, etc.; Tableaux Modernes par Diaz, Troyon, etc. . . . Dont La Vente Par suite du Décès de Madame Levaigneur (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, May 2–4, 1912), VIII, 54, (repro.), as Grande Miniature Ovale.

“Mouvement des Arts: Collection de feu Madame Levaigneur,” La Chronique des Arts et de la Curiosité, no. 19 (May 11, 1912): 151.

Catalogue of a Very Choice Collection of Works of Art: The Property of Madame Dhainaut of Paris (London: Sotheby and Co., December 10, 1936), 13, as An Attractive Miniature of a Lady.

Catalogue of Old English Silver, Fine Portrait Miniatures and Objects of Vertu (London: Sotheby and Co., July 31, 1952).

Art Prices Current (London: Art Trade Press, 1952), 29:171, as Lady.

Ross E. Taggart, ed., Handbook of the Collections in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 4th ed. (Kansas City, MO: William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts, 1959), 265, as Portrait of a Lady.

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 242, p. 79, (repro.), as Unknown Lady.

If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.