Citation

Chicago:

Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, “Nathaniel Rogers, Portrait of a Man, ca. 1825,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 1, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.3220.

MLA:

Marcereau DeGalan, Aimee. “Nathaniel Rogers, Portrait of a Man, ca. 1825,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 1, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.3220.

Artist's Biography

See the artist’s biography in volume 4.

Catalogue Entry

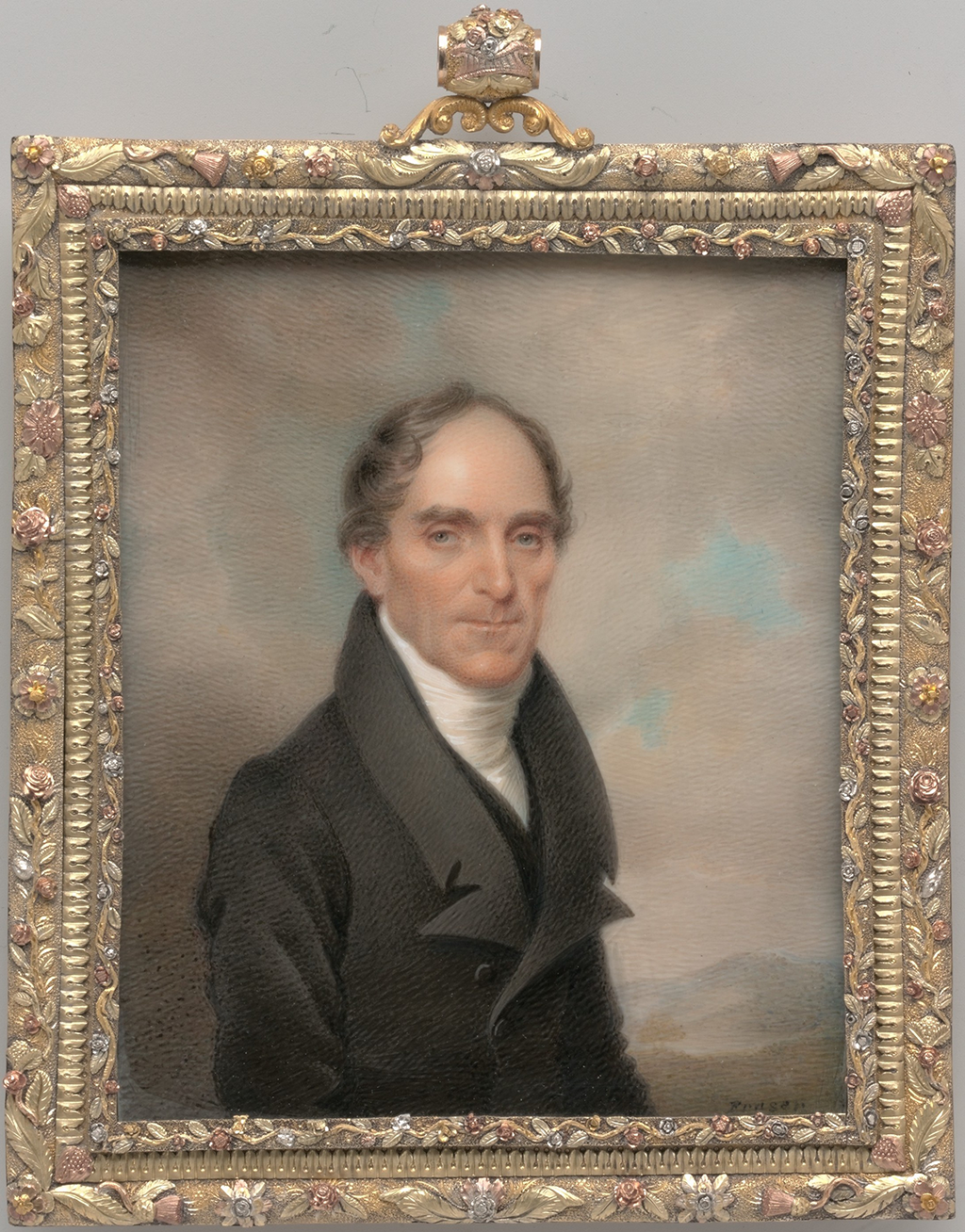

This miniature entered the collection in 1958 as a portrait by Charles Fraser (1782–1860), an artist born, raised, and based in Charleston, South Carolina. Nevertheless, Fraser’s characteristic method of modeling his figures’ faces with rough stippling: Producing a gradation of light and shade by drawing or painting small points, larger dots, or longer strokes. and hatched: A technique using closely spaced parallel lines to create a shaded effect. When lines are placed at an angle to one another, the technique is called cross-hatching., as evidenced in a portrait of his at the Metropolitan Museum (Fig. 1), is notably absent in the present picture (Fig. 2). It was not until 1992, when Robin Bolton-Smith suggested the attribution of Long Island painter Nathaniel Rogers, that the attribution shifted.1Notes on Bolton-Smith’s 1992 assessment are in the NAMA curatorial files. In 2017, during a collections assessment as part of the research for this present catalogue, Shushan and Aiken re-established the attribution to Rogers. Notes in NAMA curatorial files. For reasons that remain unclear—possibly an error of transcription during a collections assessment—the attribution changed back to Fraser at some point thereafter, and that misidentification remained in place until the commencement of work on the present catalogue. Upon close examination, scholars Elle Shushan and Carol Aiken agree that it bears all the hallmarks of Rogers’s classic early work.2Shushan and Aiken assessed the Nelson-Atkins collection over the course of several visits. Notes in NAMA curatorial files.

Rogers often signed his works, sometimes including the location on the recto: Front or main side of a double-sided object, such as a drawing or miniature. and providing sitter information on the interior backing card. However, this miniature lacks such inscriptions, so its attribution relies solely on stylistic elements. Rogers used a limited palette of dark grays, greens, blacks, and browns to delineate his figure’s form and attire. The practice of limiting one’s palette to a small number of colors was promoted by the Scottish-born miniature painter Archibald Robertson (1765–1835), who wrote a treatise on miniature painting in New York in 1800 to instruct his brother Alexander. “It ought to be an universal rule,” Robertson said, “that the fewer colors you use the better—the greater the simplicity the better.”3Emily Robertson, ed., Letters and Papers of Andrew Robertson, A. M. (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1895), 22, cited in Carol Aiken, “Materials and Techniques of the American Portrait Miniaturists,” in Dale T. Johnson, American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990), 37.

It is possible that Rogers intersected with the Robertson brothers at some point in New York, as the Rogers miniature is framed in what is a typically Scottish gold foliate: Ornamented with foliage, or leaflike decoration. case with a recto reserve. Alternatively, these types of frames could have made their way over to the United States via other émigré artists and suppliers who, like Robertson, hoped to find a stronger market there.4In a brief survey of newspaper advertisements in New York and Boston, multiple suppliers advertise miniature frames or cases imported from Europe. See advertisement for Joseph and John Del’Vecchio, Evening Post (New York), May 7, 1805, 2; “Thomas Barrow, No. 58 Broad-Street,” New-York Daily Advertiser, June 28, 1788, 4. I am grateful to Blythe Sobol, Starr research assistant, for sharing these resources. Once the frames gained currency in the 1820s and 1830s, they could have been manufactured locally. These types of foliate frames are found on many other miniatures by Rogers; thus it is likely original to the work.5Several Rogers miniatures have cases that are nearly identical to the one on the Nelson-Atkins miniature. See, for example, Nathaniel Rogers, Portrait of a Gentleman, ca. 1835, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 x 2 3/8 in. (7.2 x 6 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2006.235.164, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/14522; and Nathaniel Rogers, Portrait of a Gentleman, ca. 1830, watercolor on ivory, 2 7/8 x 2 3/8 in. (7.2 x 6.0 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1975.60.1, https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/portrait-gentleman-25061.

Despite the restricted palette, Rogers achieves remarkable individuality in his portrayal of this unidentified middle-aged man. This is particularly evident in the delicate stipple rendering of the sitter’s facial features, modeling the shadows in tones of red and emphasizing the sitter’s eyes.6See Dale T. Johnson, “Unidentified Gentleman by Nathaniel Rogers,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 50, no. 2 (Fall 1992): 52. While the sitter’s expression remains stoic, Rogers imbues the portrait with a sense of vitality, especially in the buoyancy of the subject’s hair.7Frederic Fairchild Sherman praised Rogers for his rendering of hair, along with the quality of his flesh tones. See Frederic Fairchild Sherman, “Nathaniel Rogers and His Miniatures,” Art in America 23 (October 1935): 158–62. He also renders his sitter’s clothing with crisply defined detail, using gum arabic: Derived from the sap of the African acacia tree, gum arabic was commonly used to bind watercolor pigments with water. In addition to its use as a binder, miniaturists capitalized on its glossy effect to create areas of highlight with larger quantities of gum. As with ivory, its availability benefited from trade routes that were expanding due to colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade..

Based on the cut of the man’s coat, the high collar of his white shirt, the style of his cravat: A cravat, the precursor to the modern necktie and bowtie, is a rectangular strip of fabric tied around the neck in a variety of ornamental arrangements. Depending on social class and budget, cravats could be made in a variety of materials, from muslin or linen to silk or imported lace. It was originally called a “Croat” after the Croatian military unit whose neck scarves first caused a stir when they visited the French court in the 1660s., and his upswept hair, the portrait was likely realized around 1825, when Rogers was in New York.8From 1821 to 1826, Rogers lived at 104 Liberty Street. See Natalie A Naylor, “The Legacy of Nathaniel Rogers (1787–1844), Long Island Artist from Longhampton,” Long Island Historical Journal 15 (Spring 2003), 67n8. With flourishing art academies and a growing affluent clientele, New York became a prime hub for miniaturists, attracting aspiring artists eager to learn and profit from their craft. Rogers, having transitioned from a two-year apprenticeship with Joseph Wood (1778–1830) to prominence in New York, typifies this migration of talent.9Rogers was highly skilled at painting clothing, backgrounds, and secondary areas of miniatures, and he did this for Joseph Wood during an apprenticeship from 1811 to 1813. See Johnson, American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection, 188.

Notes

-

Notes on Bolton-Smith’s 1992 assessment are in the NAMA curatorial files. In 2017, during a collections assessment as part of the research for this present catalogue, Shushan and Aiken re-established the attribution to Rogers. Notes in NAMA curatorial files.

-

Shushan and Aiken assessed the Nelson-Atkins collection over the course of several visits. Notes in NAMA curatorial files.

-

Emily Robertson, ed., Letters and Papers of Andrew Robertson, A. M. (London: Eyre and Spottiswoode, 1895), 22, cited in Carol Aiken, “Materials and Techniques of the American Portrait Miniaturists,” in Dale T. Johnson, American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1990), 37.

-

In a brief survey of newspaper advertisements in New York and Boston, multiple suppliers advertise miniature frames or cases imported from Europe. See advertisement for Joseph and John Del’Vecchio, Evening Post (New York), May 7, 1805, 2; “Thomas Barrow, No. 58 Broad-Street,” New-York Daily Advertiser, June 28, 1788, 4. I am grateful to Blythe Sobol, Starr research assistant, for sharing these resources.

-

Several Rogers miniatures have cases that are nearly identical to the one on the Nelson-Atkins miniature. See, for example, Nathaniel Rogers, Portrait of a Gentleman, ca. 1835, watercolor on ivory, 2 1/2 x 2 3/8 in. (7.2 x 6 cm), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2006.235.164, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/14522; and Nathaniel Rogers, Portrait of a Gentleman, ca. 1830, watercolor on ivory, 2 7/8 x 2 3/8 in. (7.2 x 6.0 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1975.60.1, https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/portrait-gentleman-25061.

-

See Dale T. Johnson, “Unidentified Gentleman by Nathaniel Rogers,” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 50, no. 2 (Fall 1992): 52.

-

Frederic Fairchild Sherman praised Rogers for his rendering of hair, along with the quality of his flesh tones. See Frederic Fairchild Sherman, “Nathaniel Rogers and His Miniatures,” Art in America 23 (October 1935): 158–62.

-

From 1821 to 1826, Rogers lived at 104 Liberty Street. See Natalie A Naylor, “The Legacy of Nathaniel Rogers (1787–1844), Long Island Artist from Longhampton,” Long Island Historical Journal 15 (Spring 2003), 67n8.

-

Rogers was highly skilled at painting clothing, backgrounds, and secondary areas of miniatures, and he did this for Joseph Wood during an apprenticeship from 1811 to 1813. See Johnson, American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection, 188.

Provenance

Mr. John W. (1905–2000) and Mrs. Martha Jane (1906–2011) Starr, Kansas City, MO, by 1958;

Their gift to The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1958.

Exhibitions

The Starr Foundation Collection of Miniatures, The Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, December 8, 1972–January 14, 1973, no cat., no. 230, as Unknown Man.

References

Ross E. Taggart, The Starr Collection of Miniatures in the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery (Kansas City, MO: Nelson Gallery-Atkins Museum, 1971), no. 230, p. 75, (repro.), as Unknown Man.

No known related works at this time. If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.