Citation

Chicago:

Blythe Sobol, “Unknown, Portrait of a Man, ca. 1795,” catalogue entry in Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan, The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, vol. 1, ed. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan (Kansas City, MO: Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024), https://doi.org/10.37764/8322.5.3120.

MLA:

Sobol, Blythe. “Unknown, Portrait of a Man, ca. 1795,” catalogue entry. Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, Blythe Sobol, and Maggie Keenan. The Starr Collection of Portrait Miniatures, 1500–1850: The Collections of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, edited by Aimee Marcereau DeGalan, vol. 1, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 2024. doi: 10.37764/8322.5.3120.

Catalogue Entry

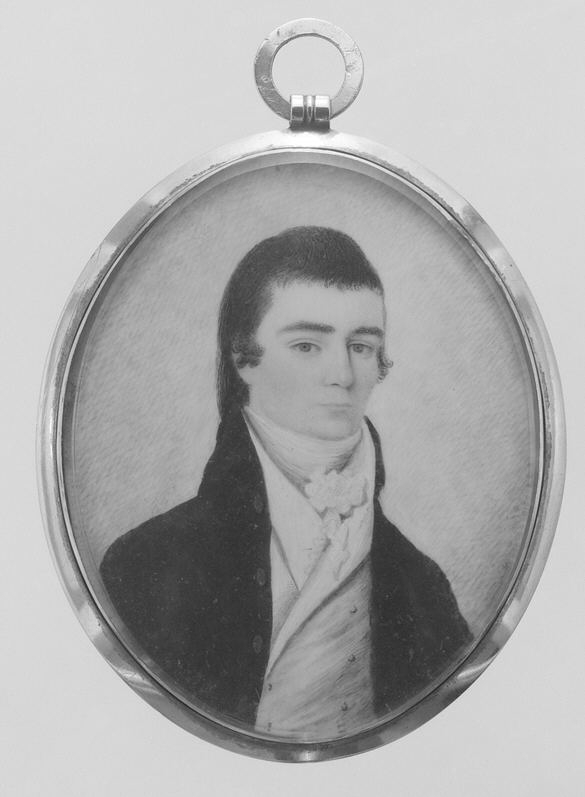

This miniature entered the Nelson-Atkins collection in 1999 with its sitter tentatively identified as Pierre Lorillard II (1764–1843), the son of a tobacco tycoon whose descendants became prominent members of New York society. Lorillard’s obituary marks the first time an American newspaper used the newfangled word “millionaire.”1Conley Dalton, Wealth and Poverty in America: A Reader (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2003), 145. Unfortunately, neither Lorillard nor his father, Pierre Lorillard I (1742–1776)—both ancestors of the donor, Joan Dillon—were of an appropriate age to have sat for this portrait, which dates to the 1790s. This depiction of an elderly man, the grooves of age carefully delineated on his face, was painted two decades after the death of Lorillard Sr. at age thirty-four,2The elder Lorillard was killed by Hessian mercenaries during the British occupation of New York in 1776. Arlene Hirschfelder, Encyclopedia of Smoking and Tobacco (London: Bloomsbury, 1999), 191. and it portrays a man too old to be his son, who was only thirty-one years old in 1795.3There is also a possibility that the portrait depicts the father of Pierre Lorillard I, Jean Lorillard (b. 1707). Jean Lorillard immigrated to Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1753, as part of a group of more than four hundred Huguenots from Montbeliard, France, which had long been an enclave for French Protestants. Perhaps Jean Lorillard visited his son in New York and had his likeness taken by a miniaturist; he would have been at least eighty-three at the time of his visit. Adrien Quélet, “Jean Georges Lorillard,” Geneanet, https://gw.geneanet.org/adrienquelet?n=lorillard&oc=&p=jean+georges. For more on the Monbéliard Huguenots in Nova Scotia, see Terrence M. Punch, Montbéliard Immigration to Nova Scotia, 1749–1752 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2014). Another of Dillon’s relatives, Gabriel Furman (1756–1844), was also too young to be the subject; nevertheless, the portrait probably does depict a member of Dillon’s family—perhaps Moss Kent (1733–1794), although there are no known portraits of Kent to compare.

We do know that this miniature was almost certainly painted in New York. While it can be difficult to confirm conclusively that a portrait and a case are original to one another, it is plausible that this miniature, which dates to about 1795, and its mount, which is of a design made in New York from about 1790 to 1810, were made around the same time. This case style, with a sturdy circular hanger mounted to the smooth gold bezel: A groove that holds the object in its setting. More specifically, it refers to the metal that holds the glass lens in place, under which the portrait is set. with a bracket marked with linear vertical grooves, is commonly called a “New York case” (Fig. 1).4In conversation with Carol Aiken and Elle Shushan, 2017 and 2018; notes in NAMA curatorial files.

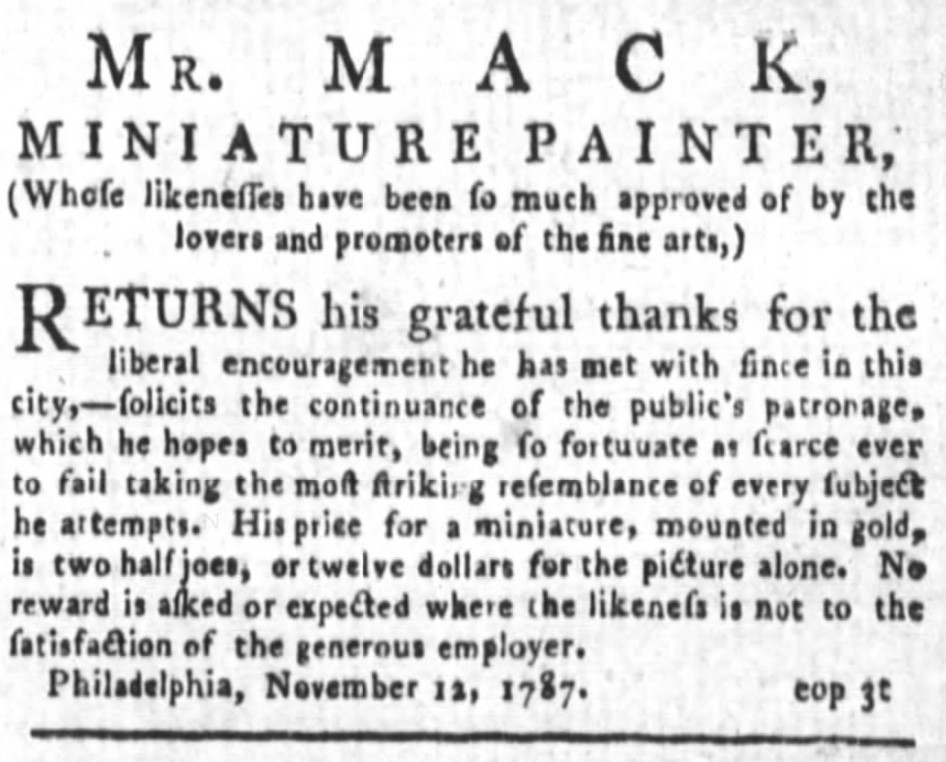

The miniature’s artist is more difficult to pin down. Dozens of portrait miniaturists advertised in New York newspapers like the Weekly Museum, but their names are no longer connected to their works, many of which remain unidentified. One outlier is Ebenezer Mack (1755–1826), who advertised his miniature portraits in New York between 1791 and 1808 (Fig. 2).5Michael Tormey, “Featured Artist: Ebenezer Mack (1755–1826),” Michael’s Museum, August 11, 2017, http://michaelsmuseum.com/articles/Mack.pdf. See also Carrie Rebora Barratt and Lori Zabar, American Portrait Miniatures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010), 62. The spattered appearance of this miniature’s background, created with loose stippling: Producing a gradation of light and shade by drawing or painting small points, larger dots, or longer strokes. in shades of blue and green, contrasted with fine stippling in the face, the almond-shaped eyes, and the lips—which are separated by a fine dark line—resemble Mack’s characteristic style. Several of his miniatures depict his sitters with fuzzily rendered beetle brows similar to those in this portrait (Fig. 3). However, the detailing in the clothing and the depiction of the features and flesh tones are more finely and sensitively painted than is typical for Mack. Mack was probably self-taught, but perhaps he knew the artist of this miniature or saw examples of his work during his time in New York and strove to emulate them in his own paintings.

Notes

-

Conley Dalton, Wealth and Poverty in America: A Reader (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2003), 145.

-

The elder Lorillard was killed by Hessian mercenaries during the British occupation of New York in 1776. Arlene Hirschfelder, Encyclopedia of Smoking and Tobacco (London: Bloomsbury, 1999), 191.

-

There is also a possibility that the portrait depicts the father of Pierre Lorillard I, Jean Lorillard (b. 1707). Jean Lorillard immigrated to Nova Scotia, Canada, in 1753, as part of a group of more than four hundred Huguenot: A French Protestant who followed the teachings of John Calvin (1509–1564). Protestantism and particularly Calvinism were strongly opposed by the French Catholic government. Huguenots faced centuries of persecution in France, and the vast majority immigrated to other countries, including Great Britain and Switzerland, by the early eighteenth century. Due to their belief that wealth acquired through honest work was godly, Huguenot refugees in these countries brought with them a strong tradition of skilled artmaking and craftsmanship, particularly in silver and goldsmithing, silk weaving, and watchmaking. See also Edict of Nantes. from Montbeliard, France, which had long been an enclave for French Protestants. Perhaps Jean Lorillard visited his son in New York and had his likeness taken by a miniaturist; he would have been at least eighty-three at the time of his visit. Adrien Quélet, “Jean Georges Lorillard,” Geneanet, https://gw.geneanet.org/adrienquelet?n=lorillard&oc=&p=jean+georges. For more on the Monbéliard Huguenots in Nova Scotia, see Terrence M. Punch, Montbéliard Immigration to Nova Scotia, 1749–1752 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2014).

-

In conversation with Carol Aiken and Elle Shushan, 2017 and 2018; notes in NAMA curatorial files.

-

Michael Tormey, “Featured Artist: Ebenezer Mack (1755–1826)," Michael’s Museum, August 11, 2017, http://michaelsmuseum.com/articles/Mack.pdf. See also Carrie Rebora Barratt and Lori Zabar, American Portrait Miniatures in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2010), 62.

Provenance

Inherited by Emily Kent (née Lorillard, 1858–1910), Tuxedo Park, NY, by 1901–1910 [1];

By descent to her son, Richard Kent (1894–1964), 1910–1964;

By descent to his daughter, Joan Kent Dillon (1925–2009), Chatham, MA, and Kansas City, MO, by 1970–1999 [2];

Her gift to the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, MO, 1999.

Notes

[1] The acquisition paperwork for this miniature records its provenance as an inheritance to Dillon from her “Lorillard Family.” Through this, we can ascertain that it was passed down from the paternal side of Dillon’s family, through her father Richard Kent (1894–1964), who would have received them from his mother, Emily Lorillard (1858–1910). It is possible that she had received the miniature from her father, Pierre Allien Lorillard (1833–1901) by the time of his death in 1901, but we have been unable to confirm this. Acquisition Proposal, 1999, NAMA curatorial files.

[2] Dillon would most likely have received the miniature either upon her father Richard Kent’s death in 1964, or when her mother, Gladys Schroeder Kent (1899–1970) died in 1970.

No known related works, exhibitions, or references at this time. If you have additional information on this object, please tell us more.